Dutch Master

A conversation with designer Hans Teensma (Outside, New England Monthly, Orion, more)

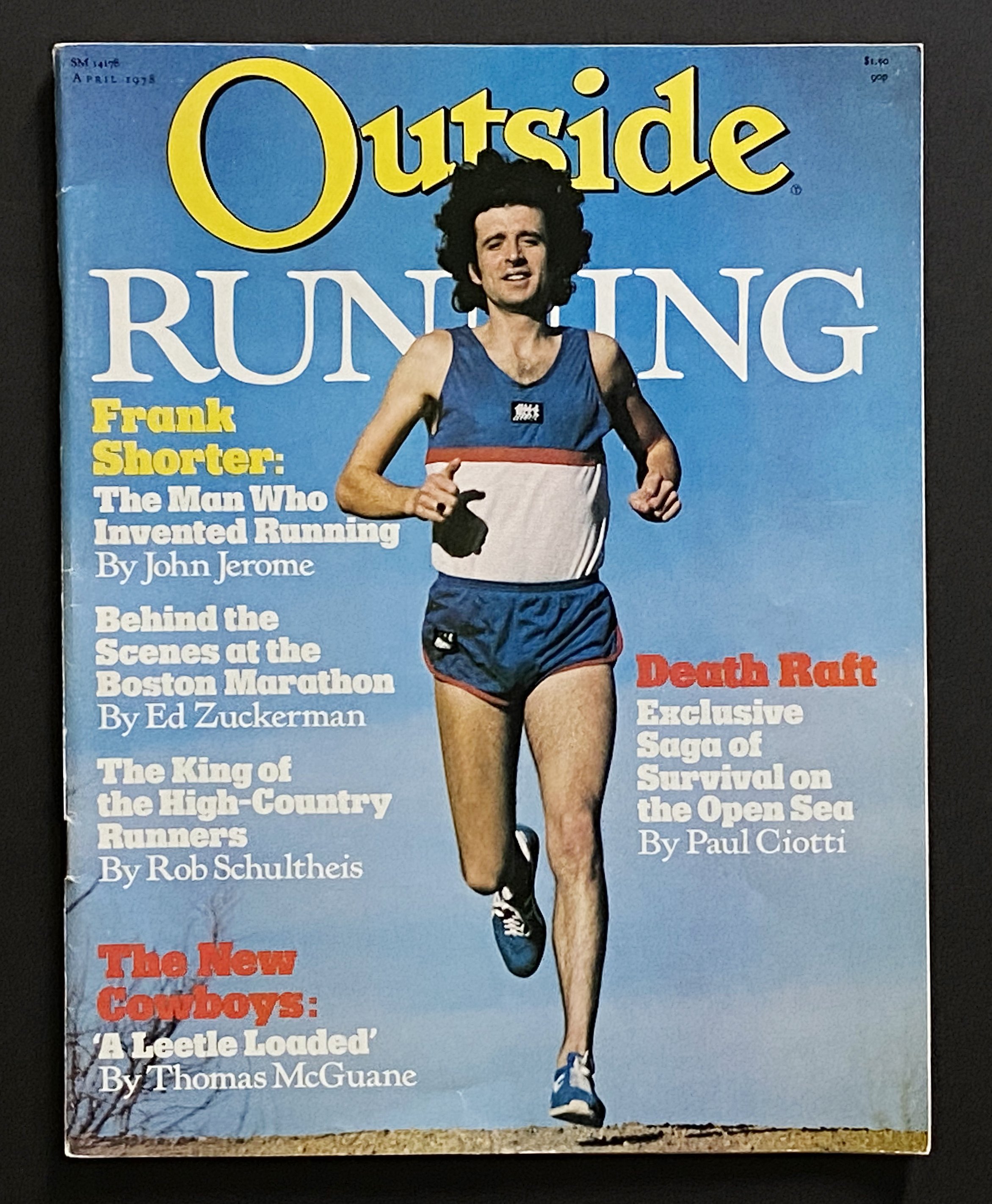

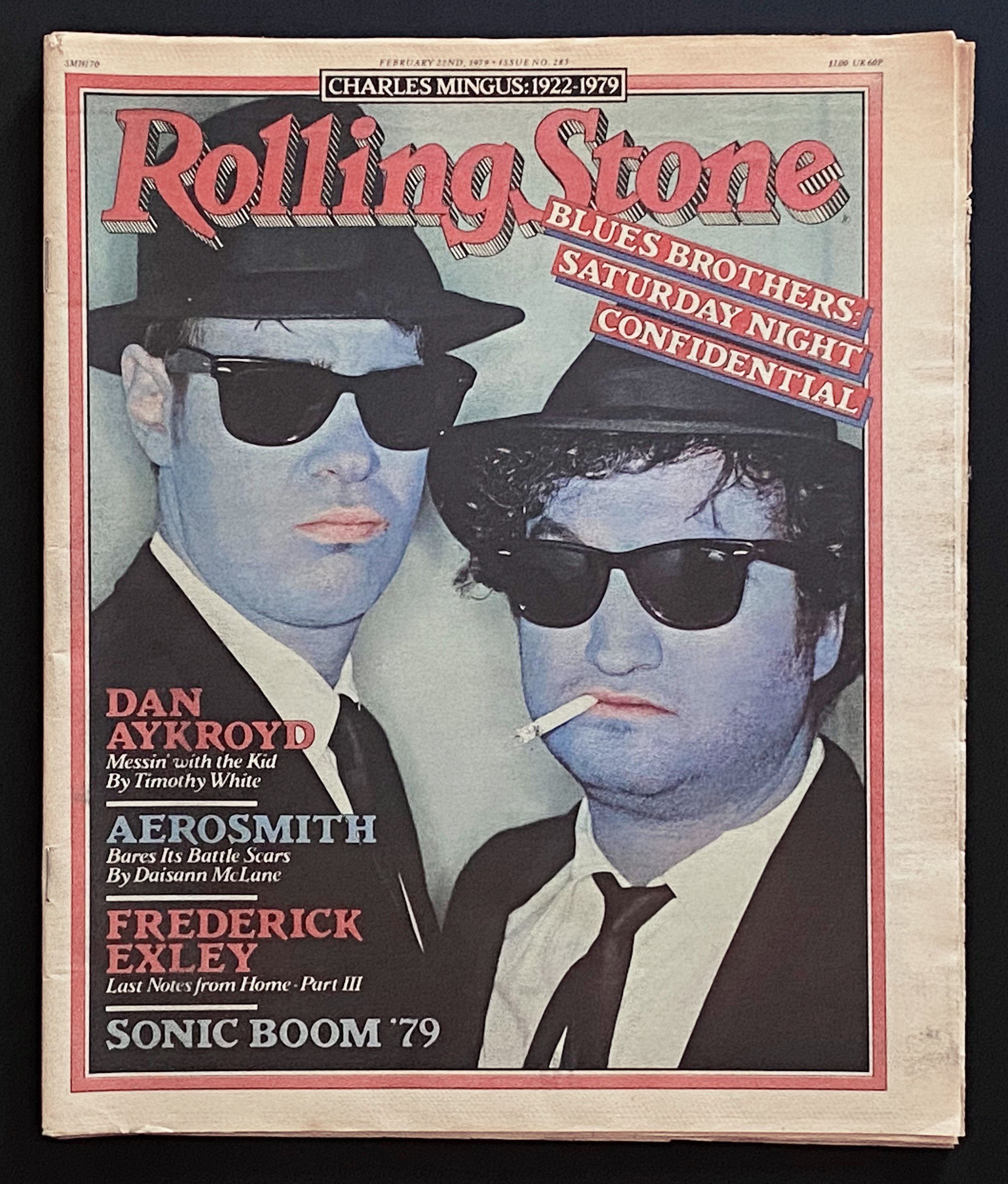

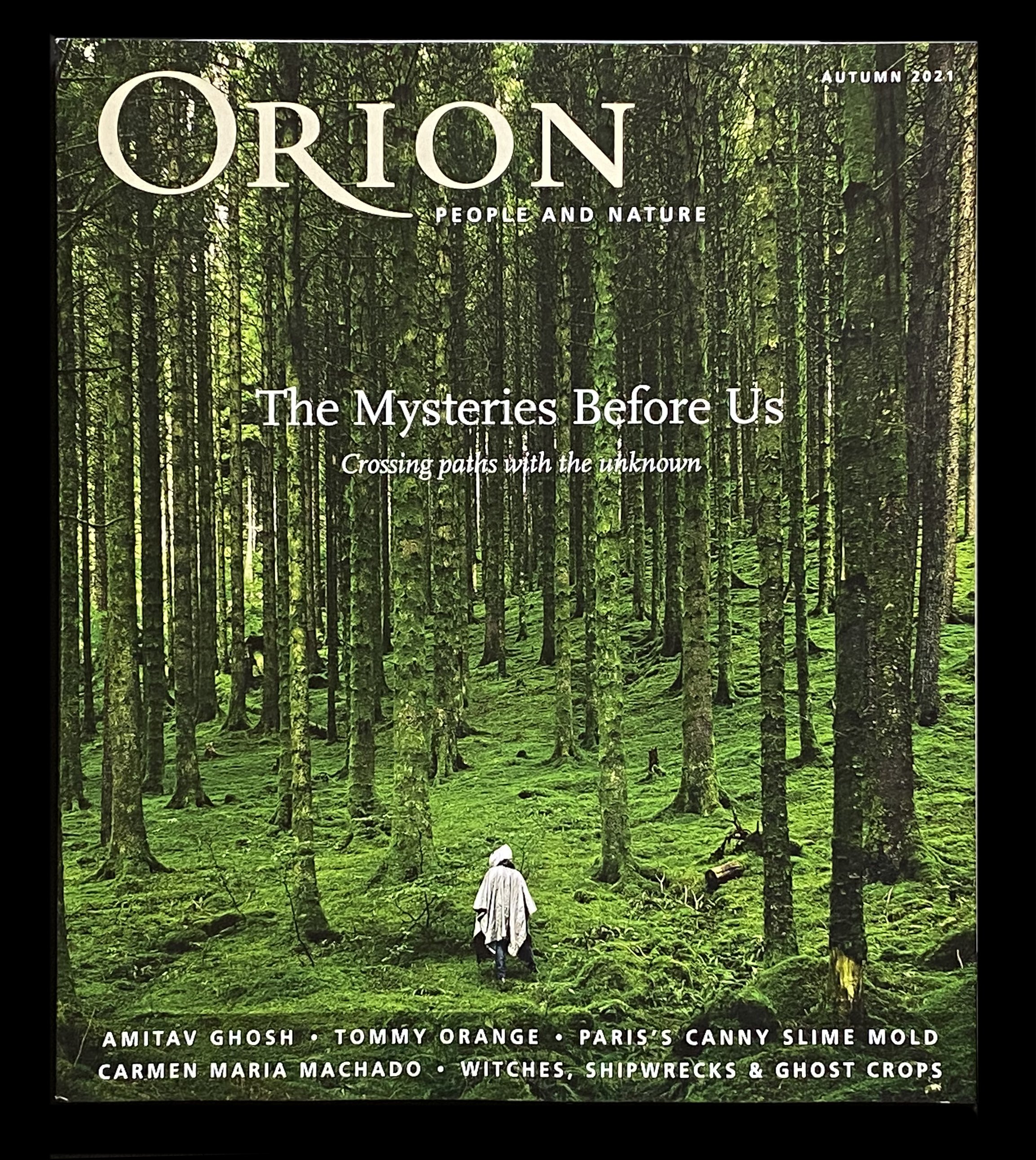

Dutch-born, California-raised designer Hans Teensma began his magazine career working alongside editor Terry McDonell at Outside magazine, which Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner launched in San Francisco in 1977.

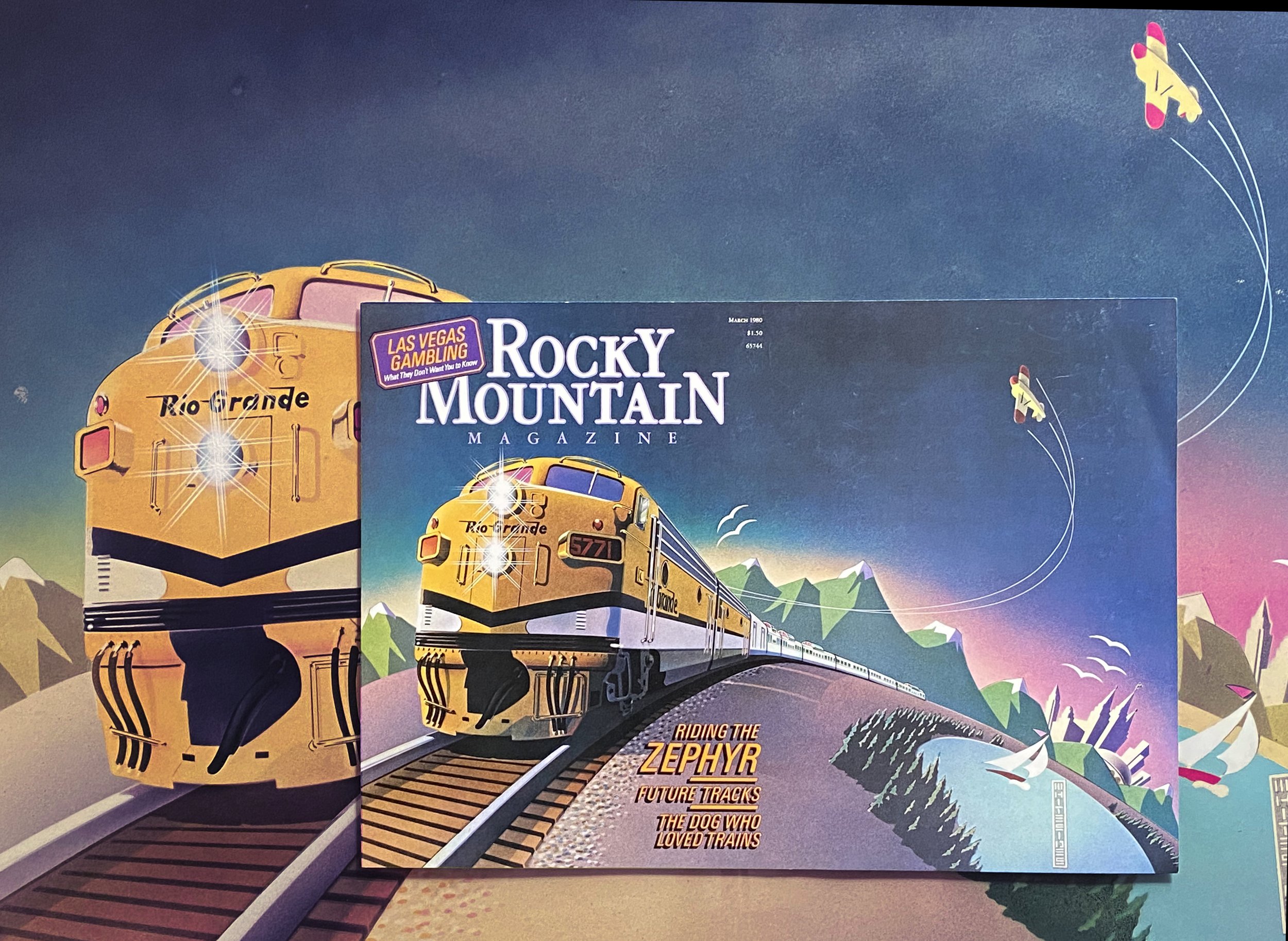

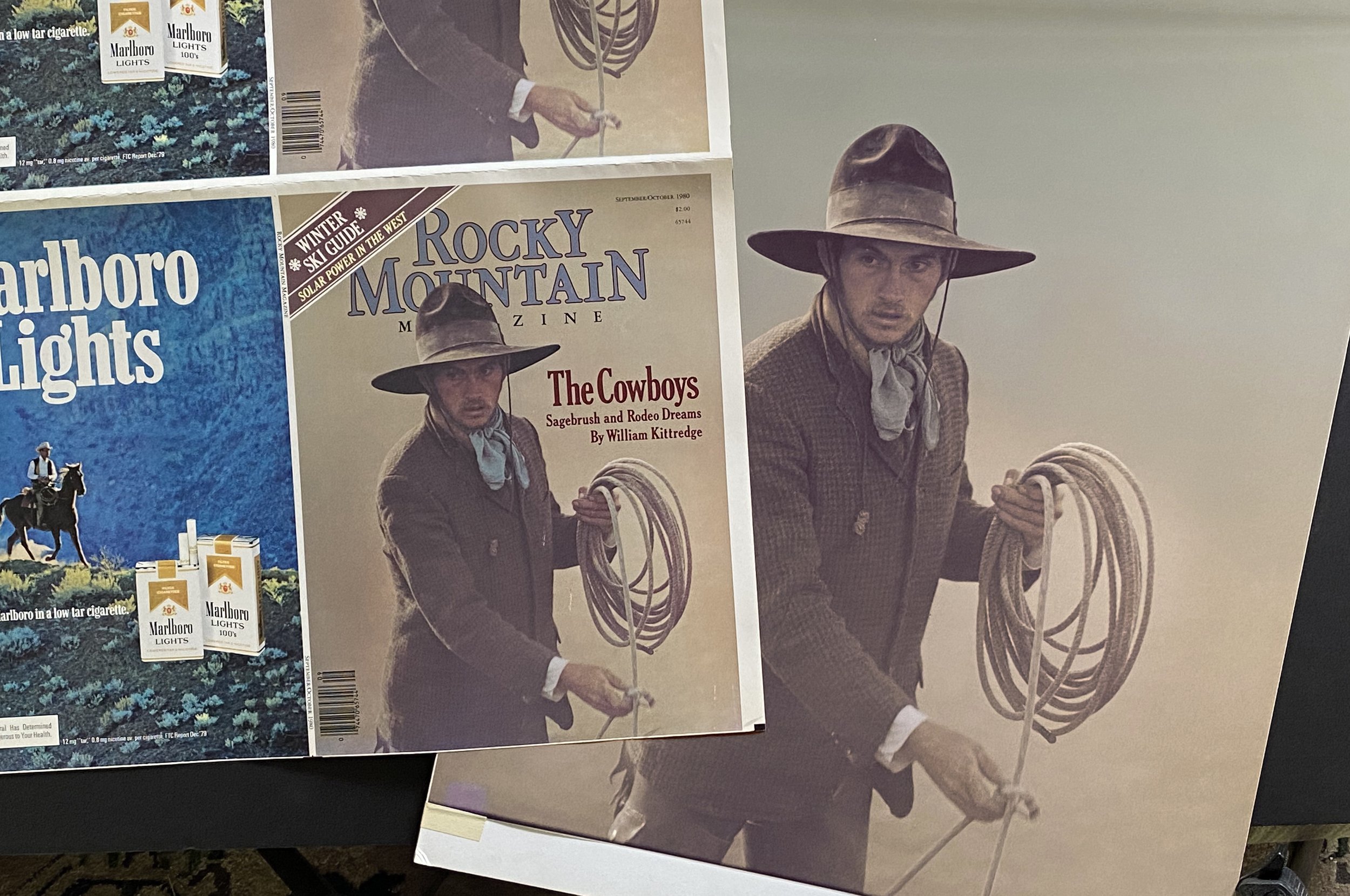

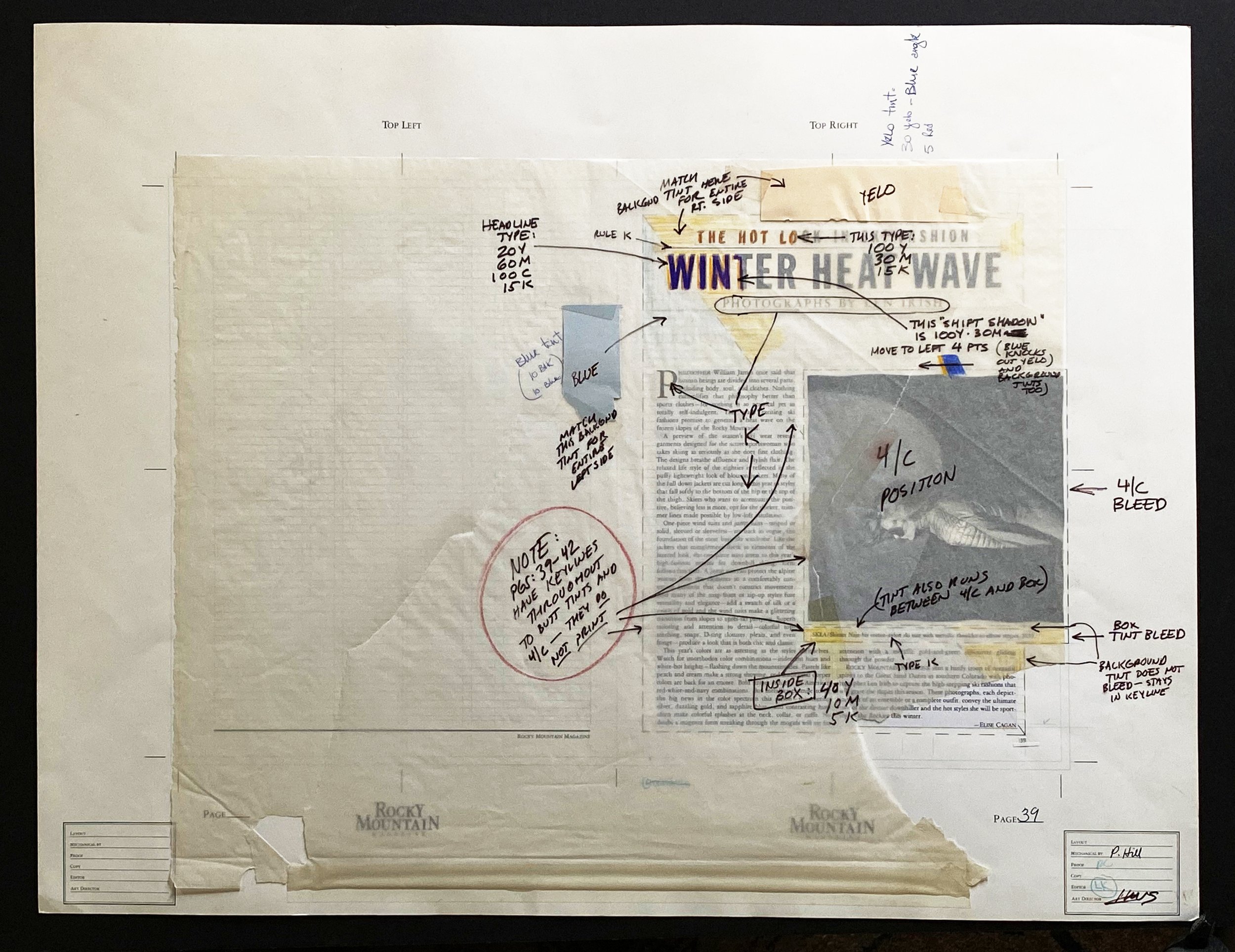

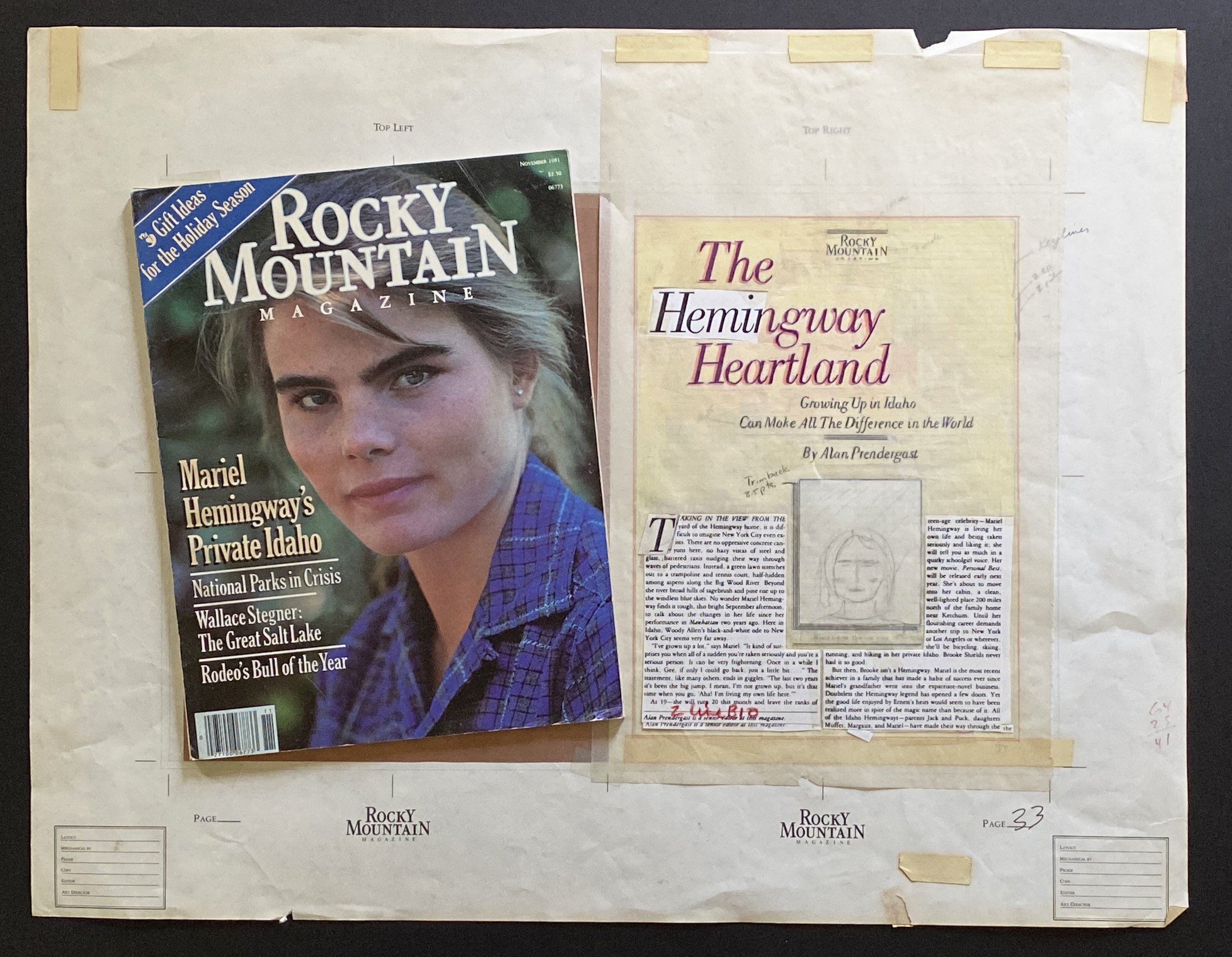

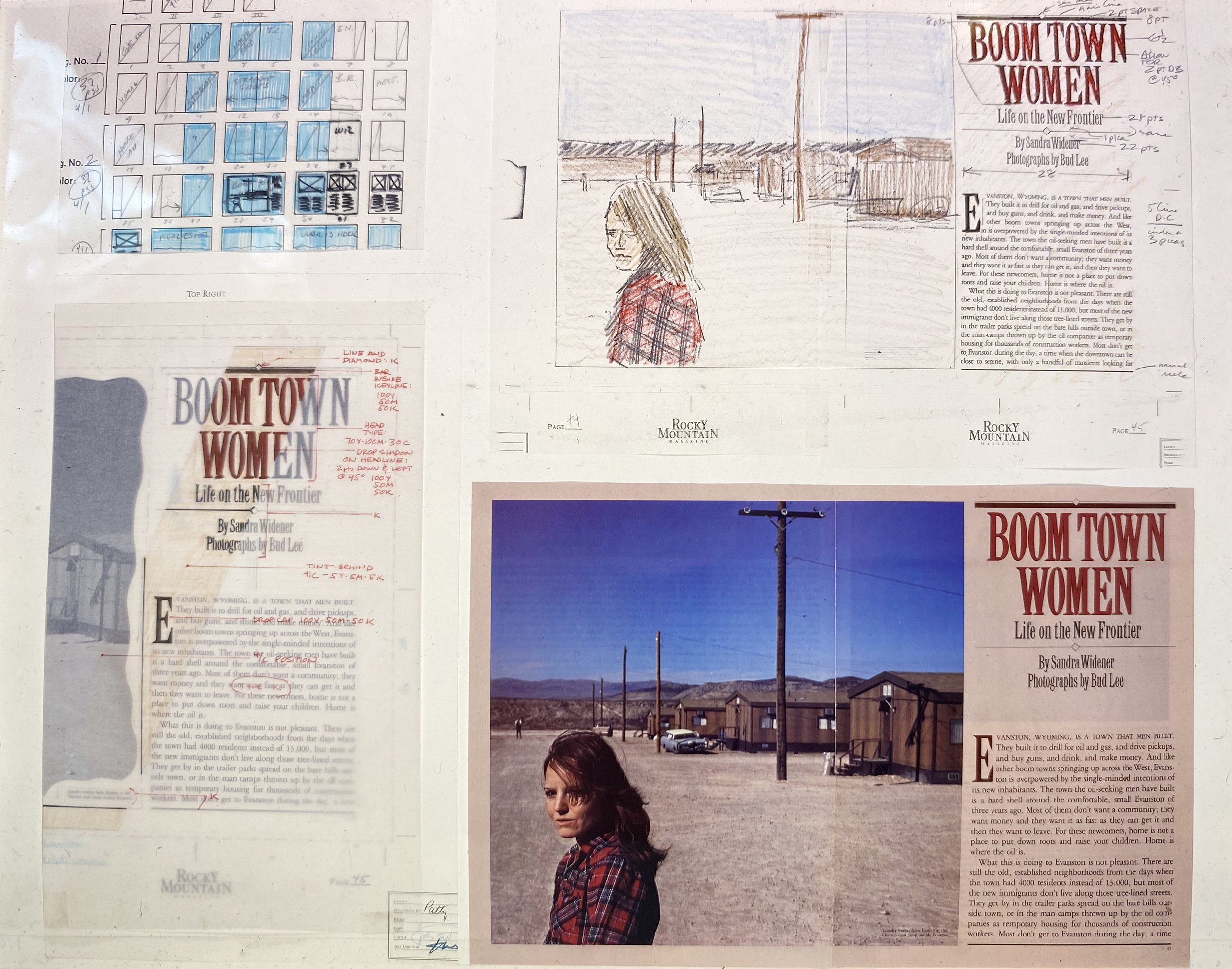

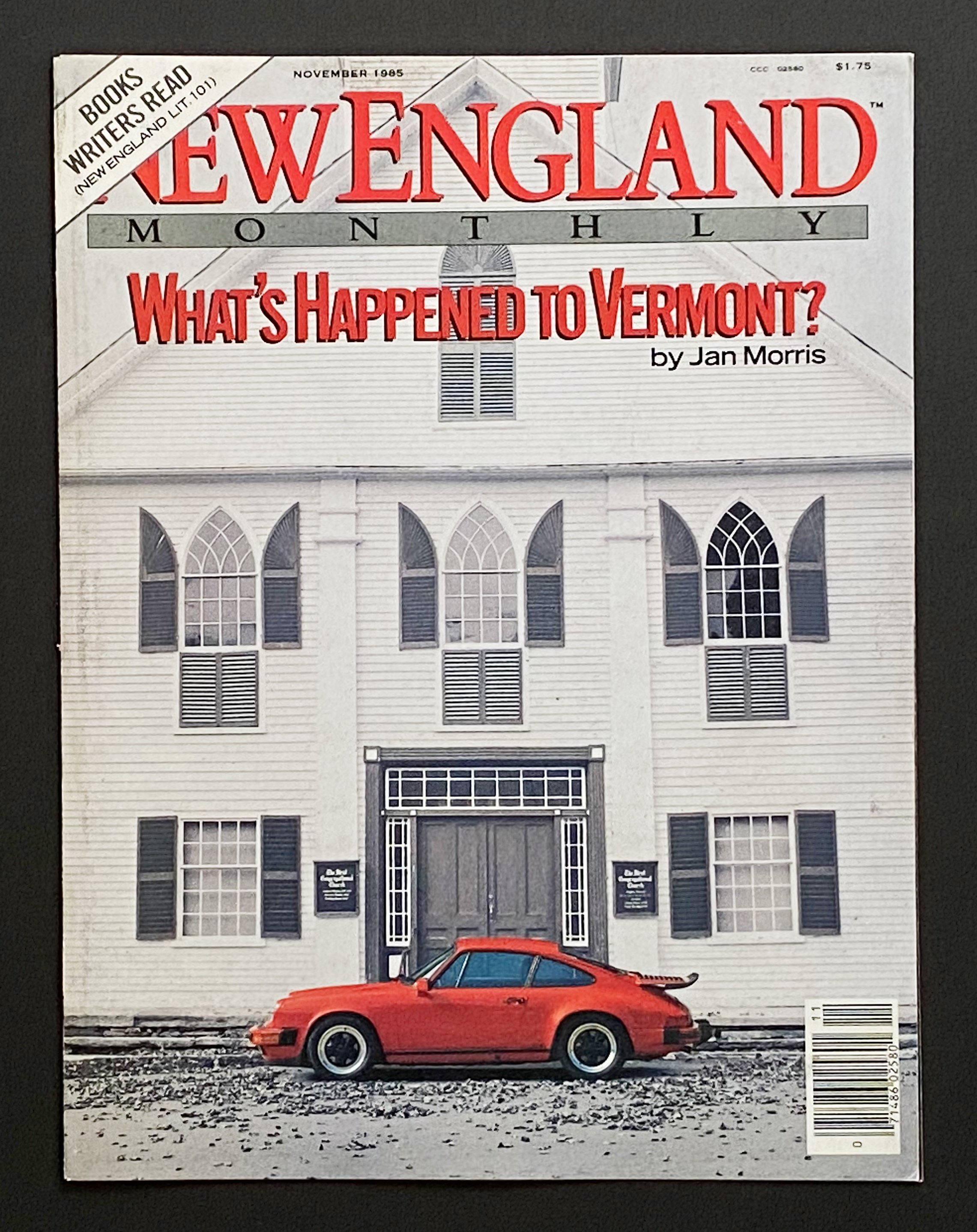

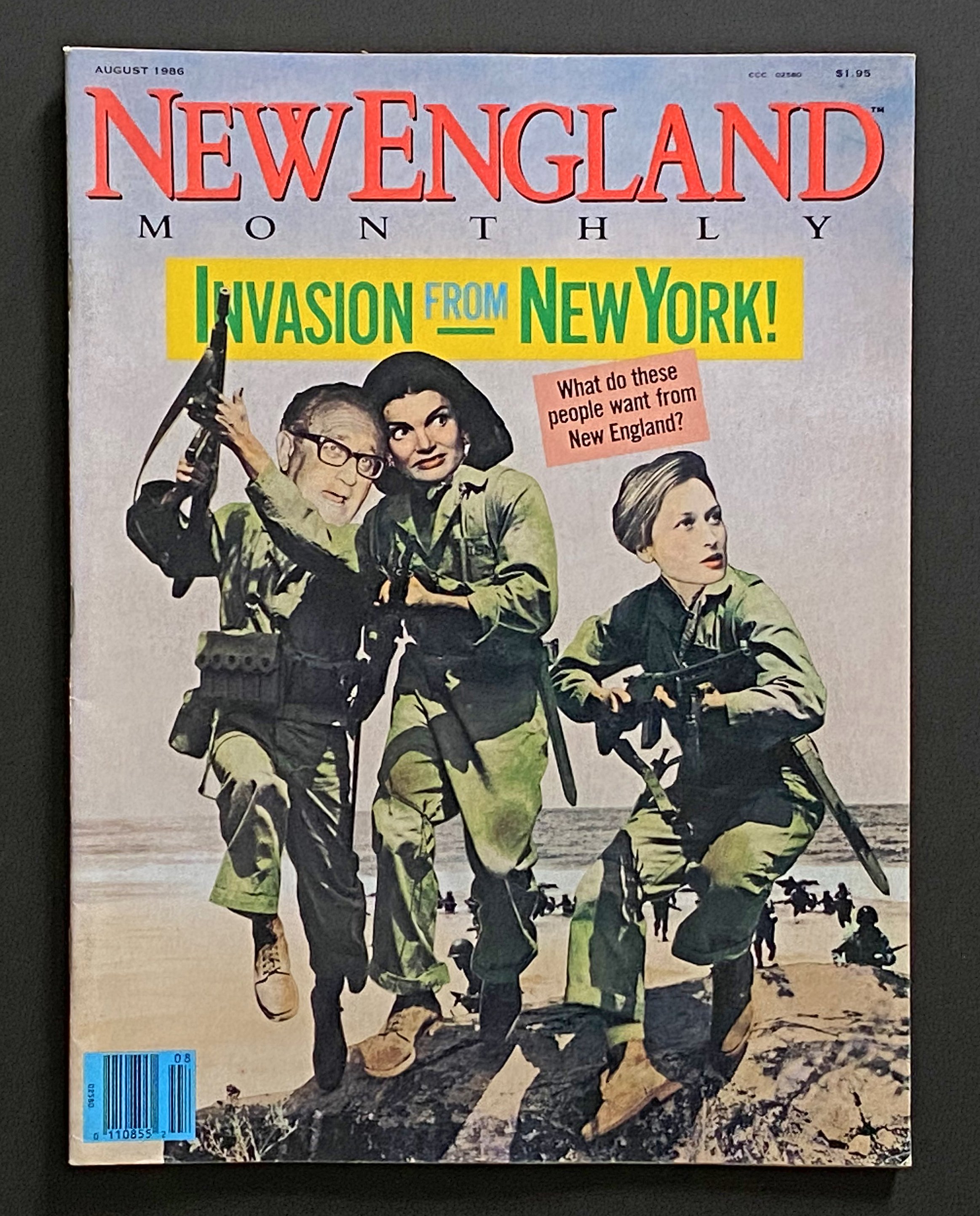

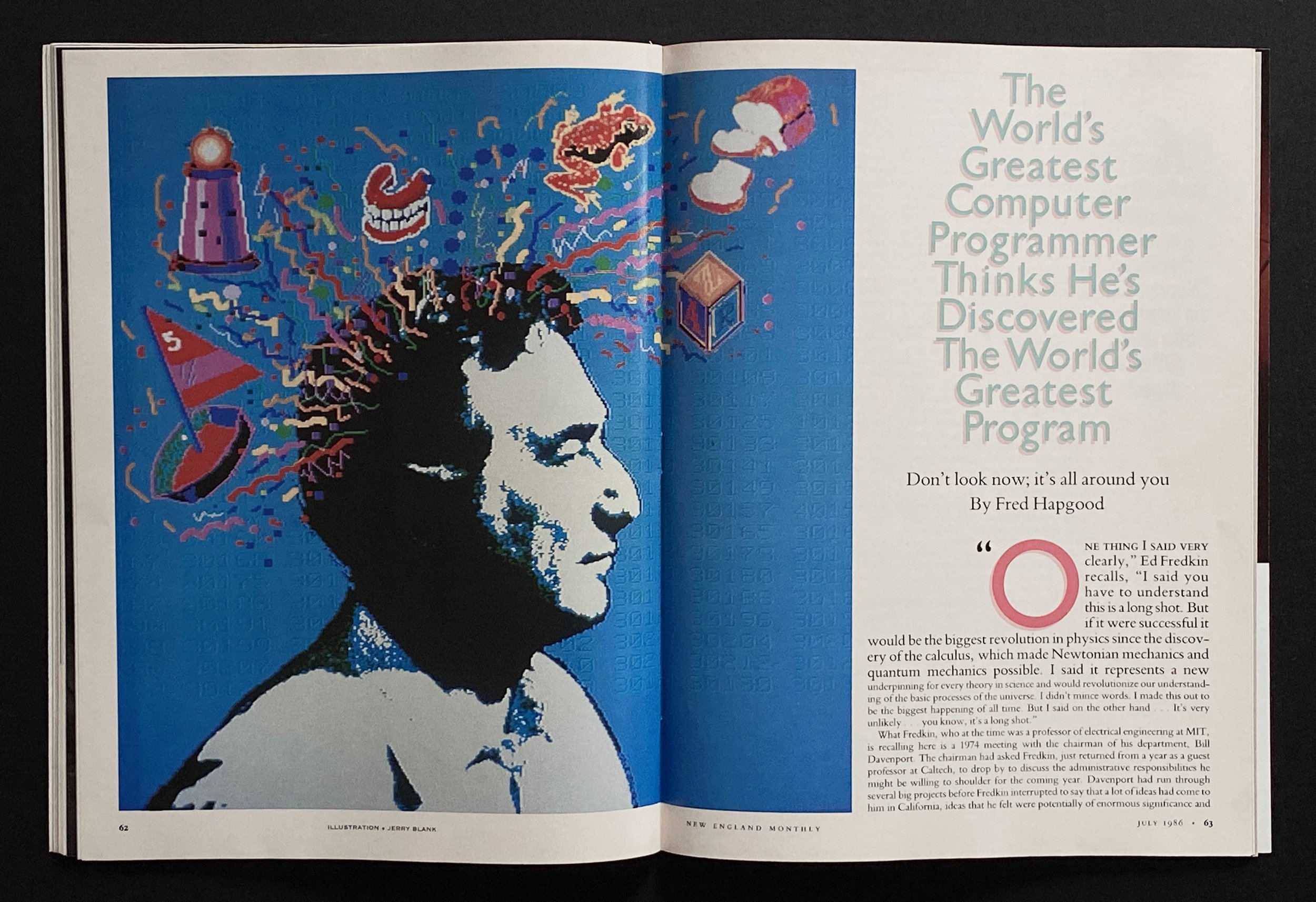

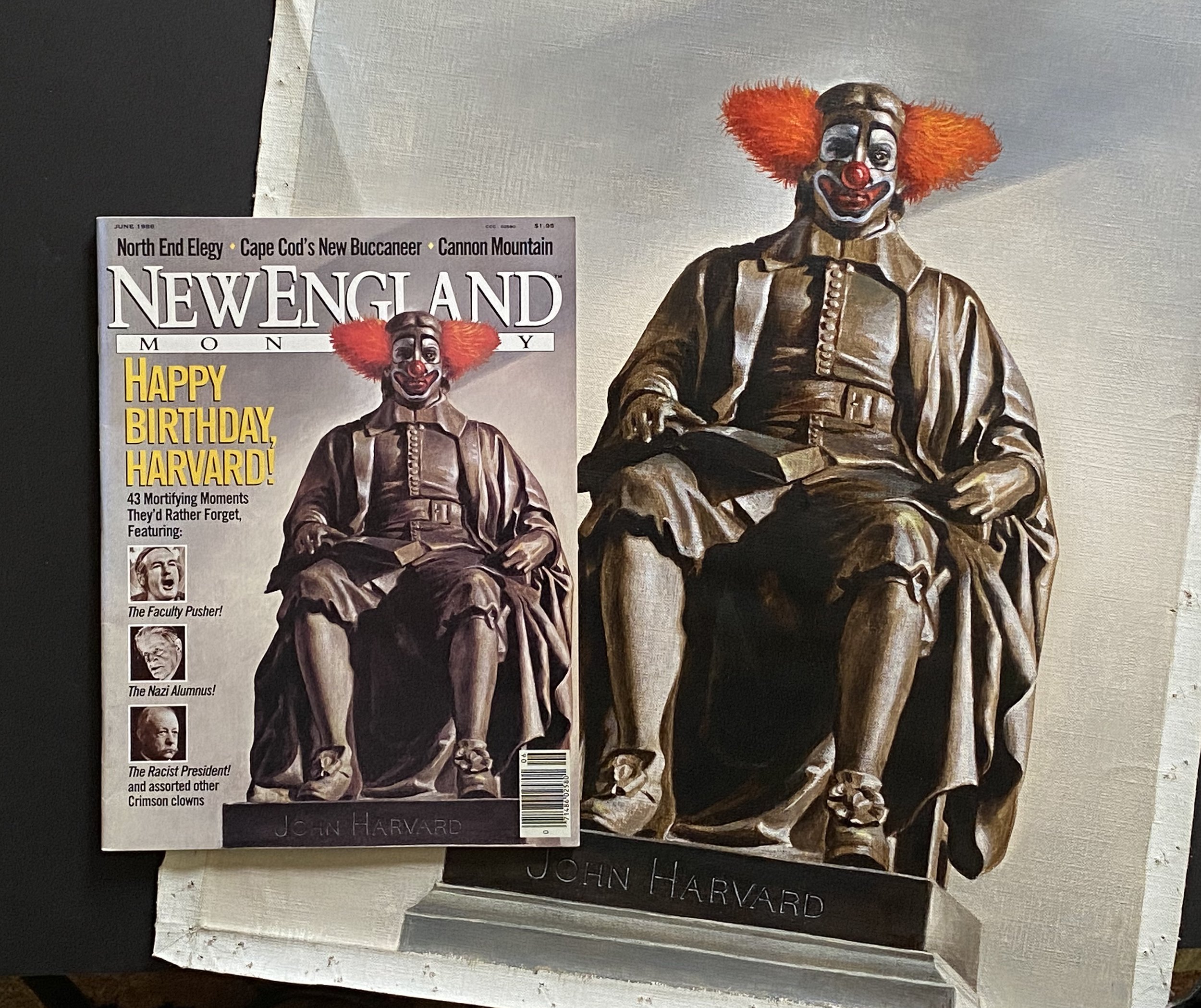

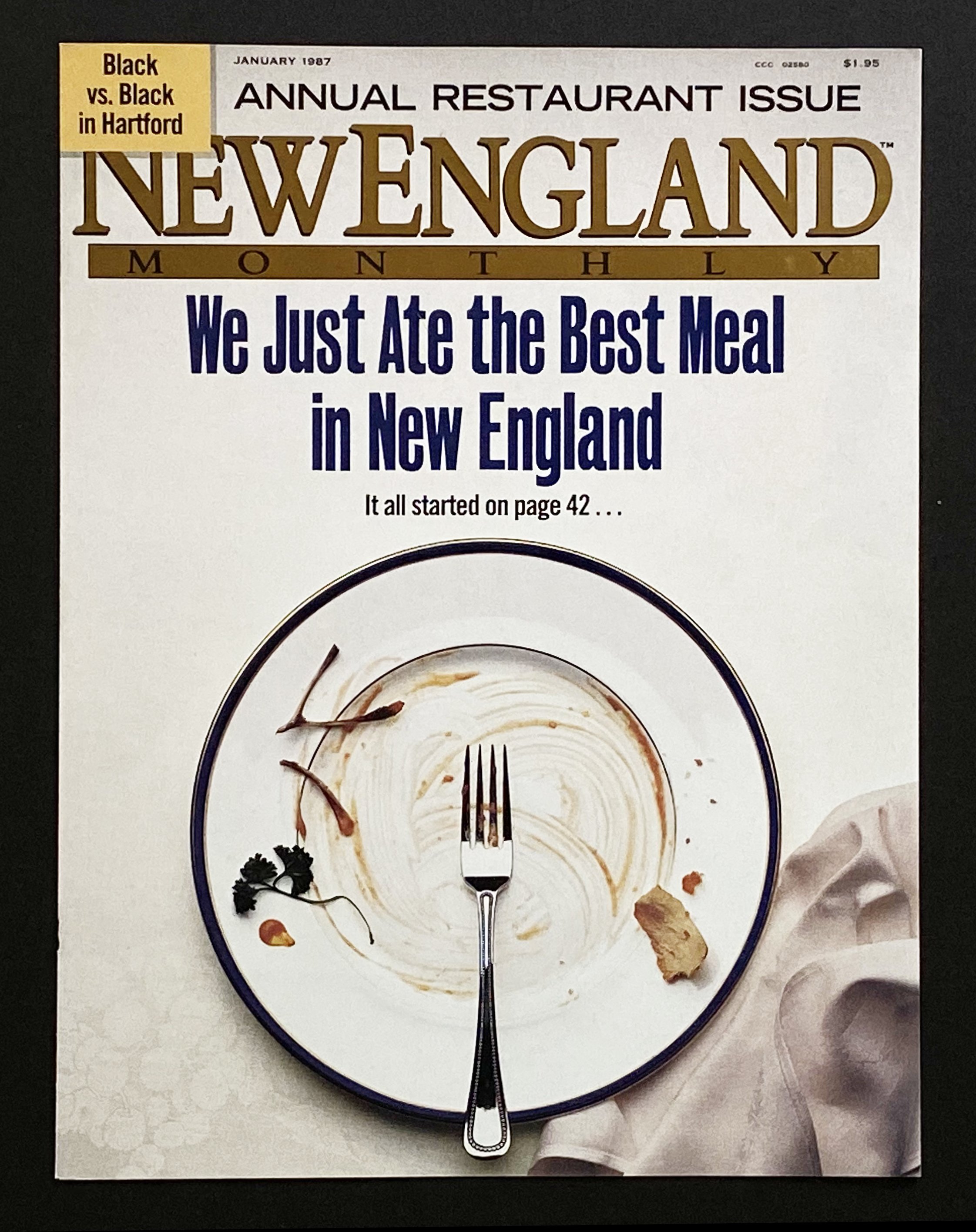

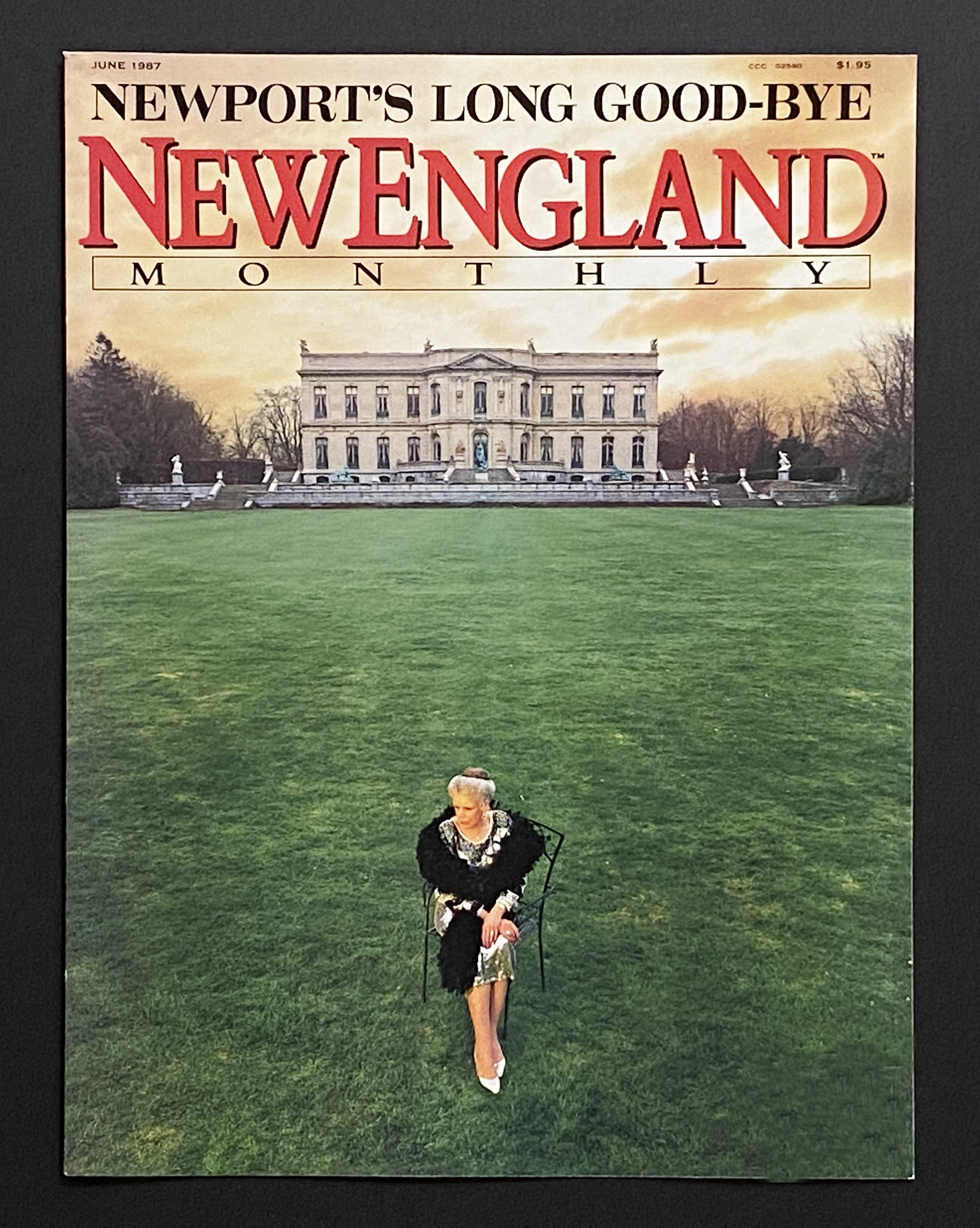

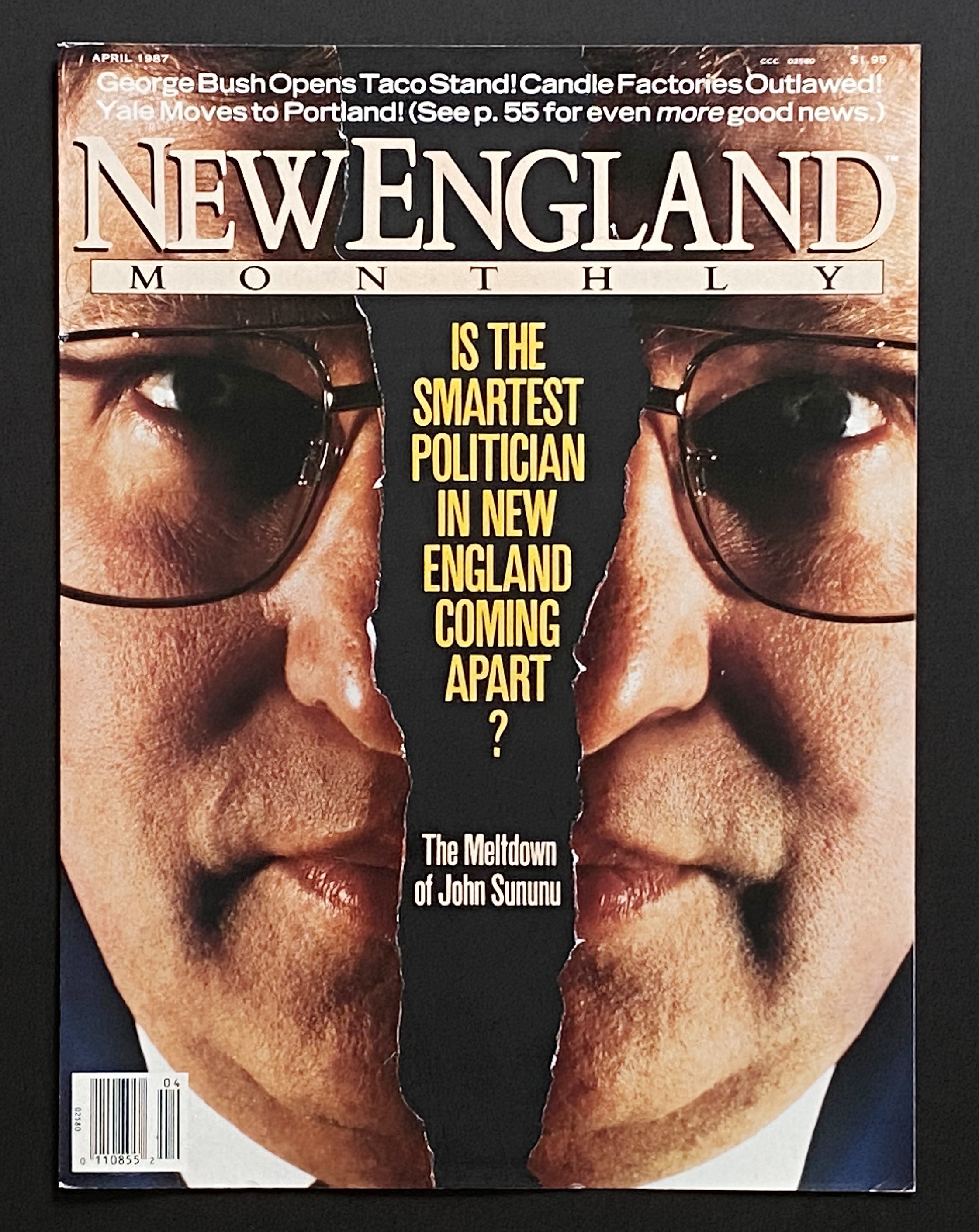

When Wenner sold Outside two years later, Teensma and McDonell headed to Denver to launch a new regional, Rocky Mountain Magazine, which would earn them the first of several ASME National Magazine Awards. On the move again, Teensma’s next stop would be New England Monthly, another launch with another notable editor, Dan Okrent. The magazine was a huge hit, financially and critically, and won back-to-back ASME awards in 1986 and ’87.

Ready for a new challenge—and ready to call New England home—Teensma launched his own studio, Impress, in the tiny village of Williamsburg, Massachusetts. The studio has produced a wide range of projects, including startups and redesigns, as well as pursuing Teensma’s passion for designing books.

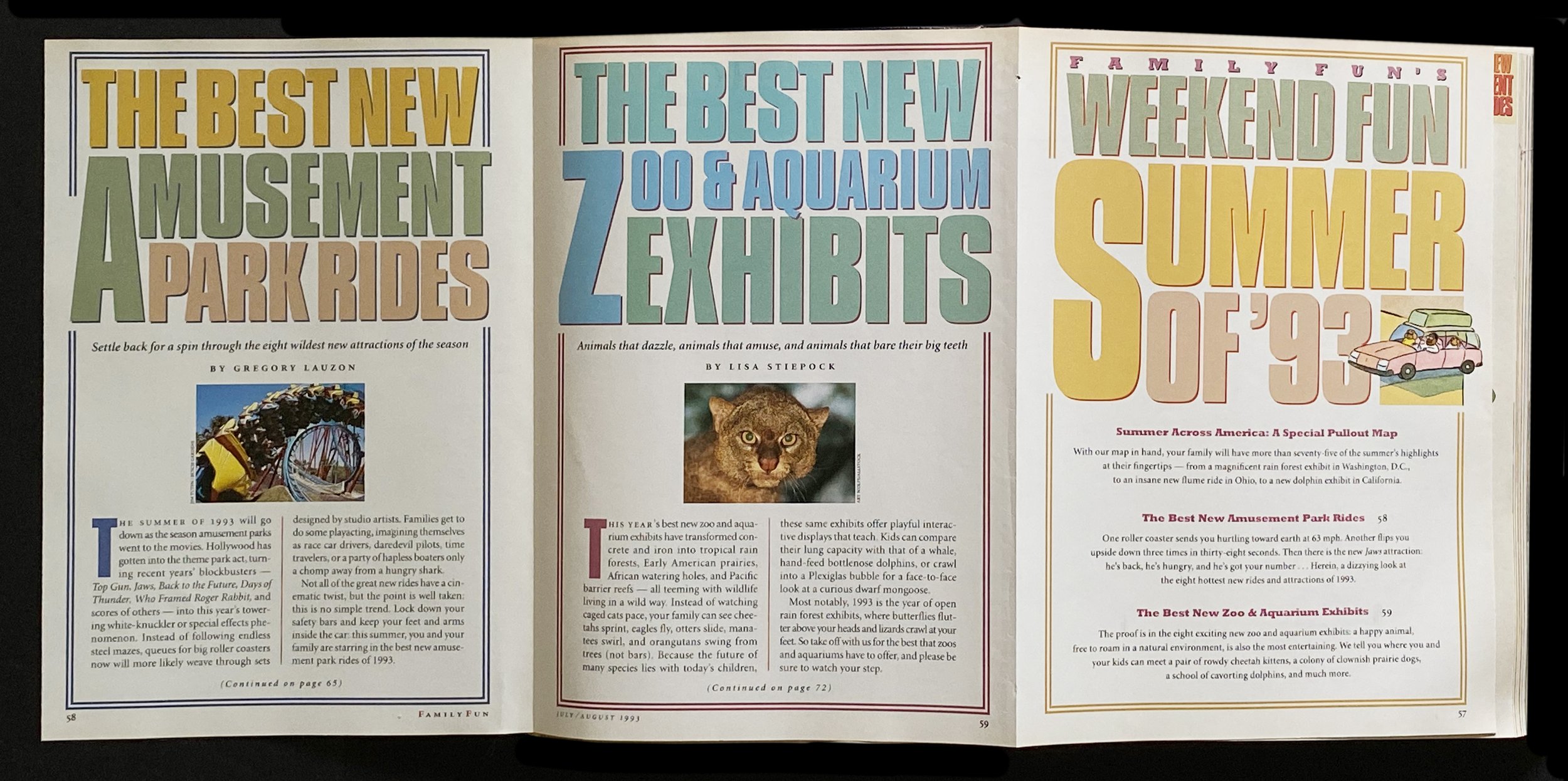

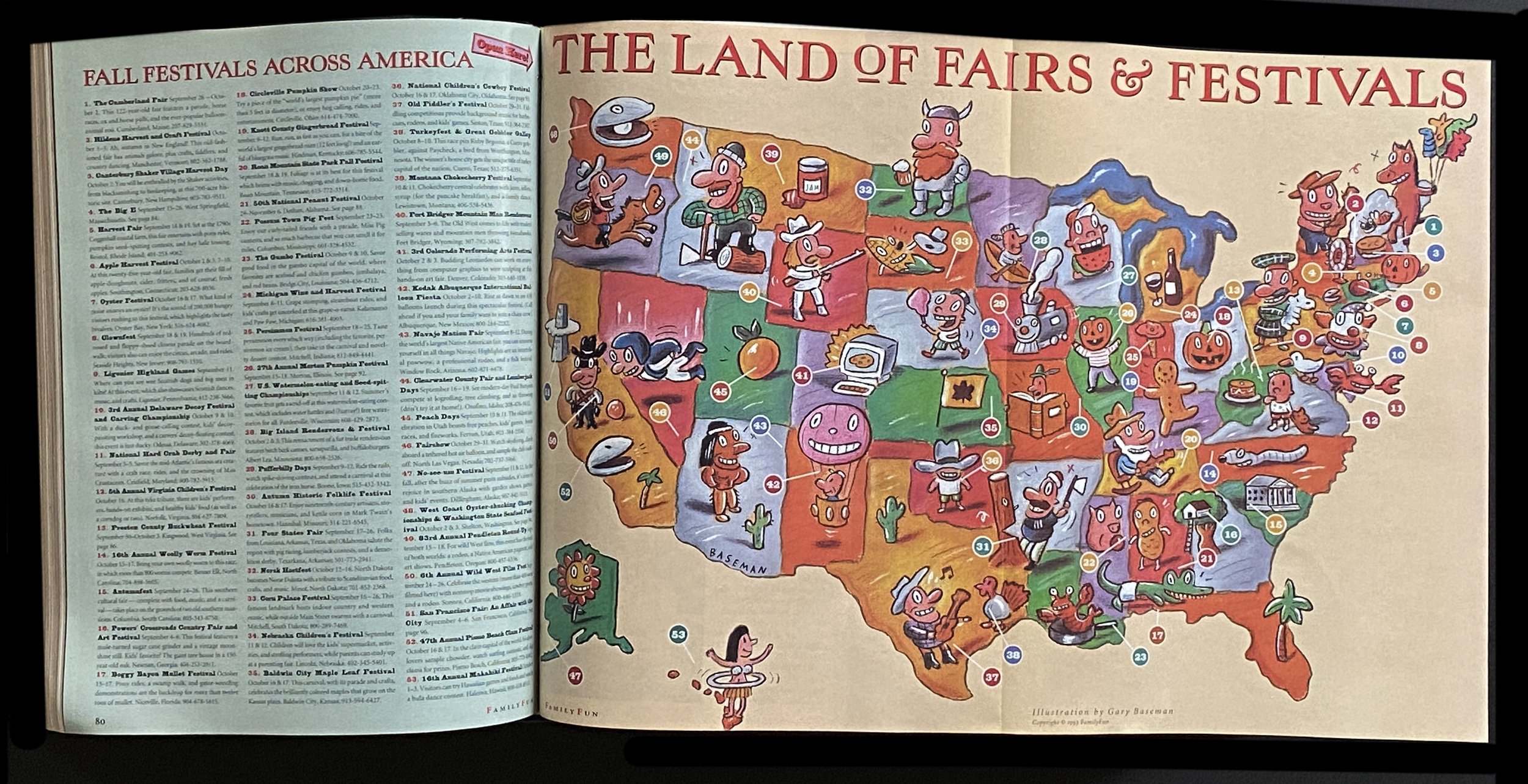

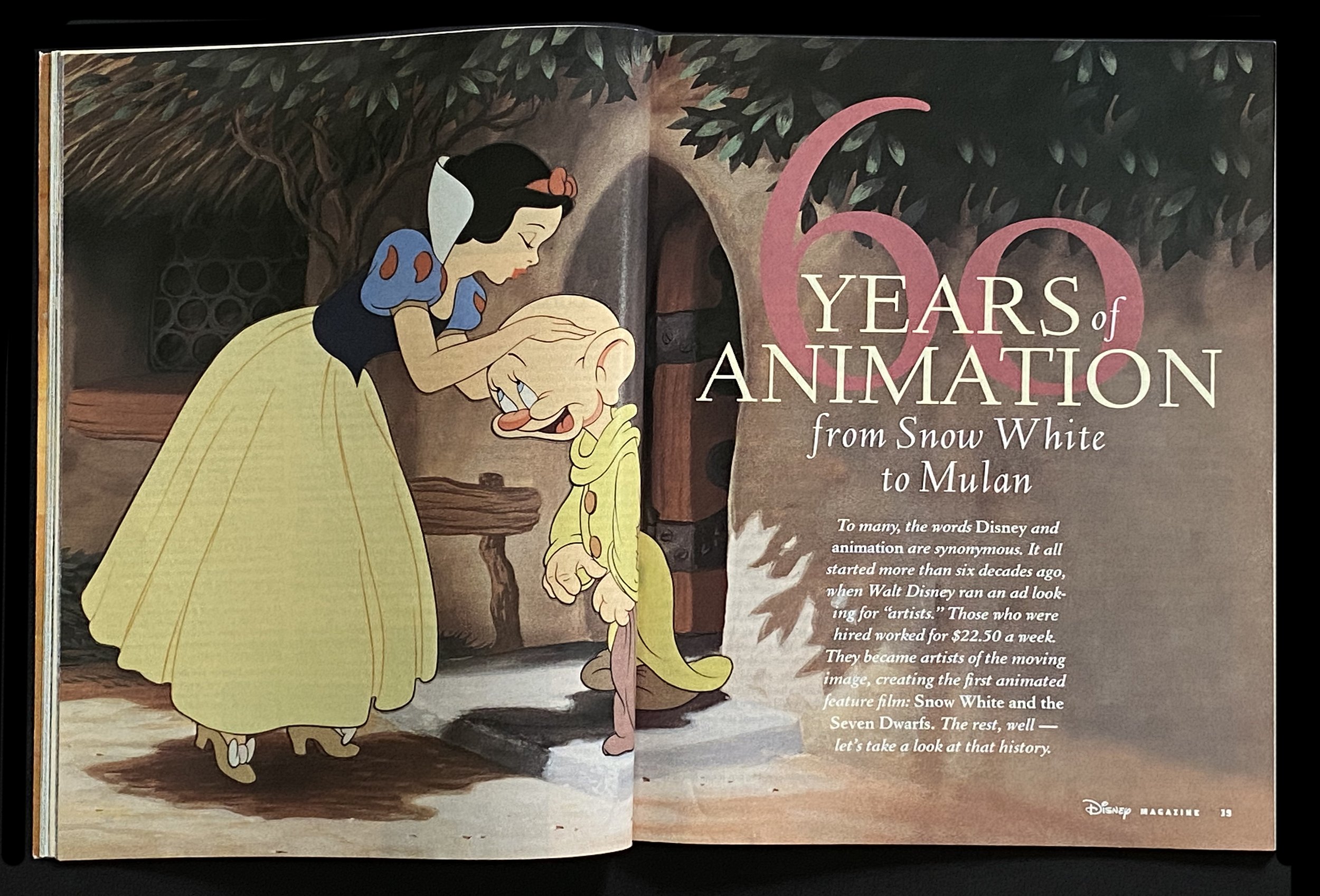

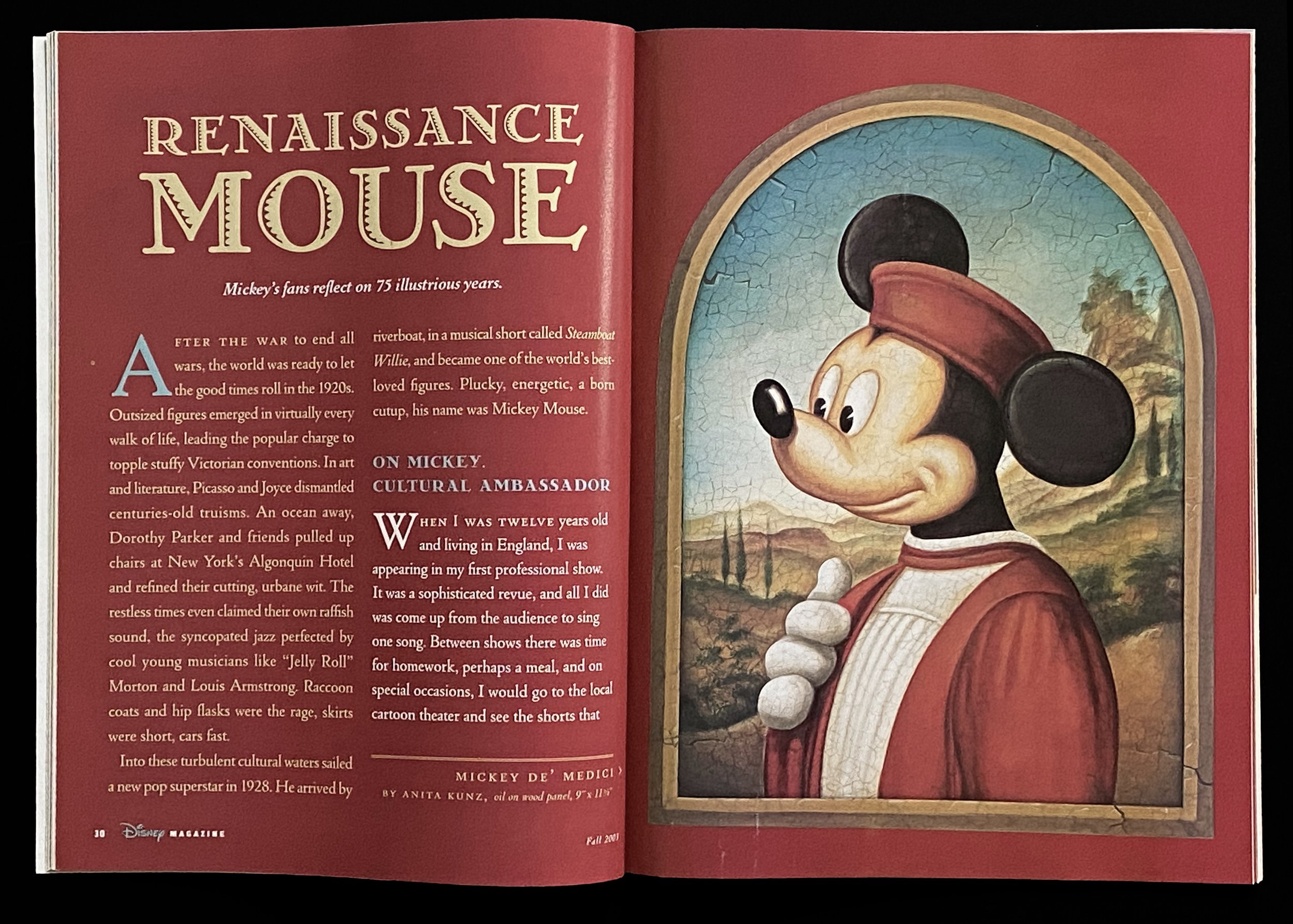

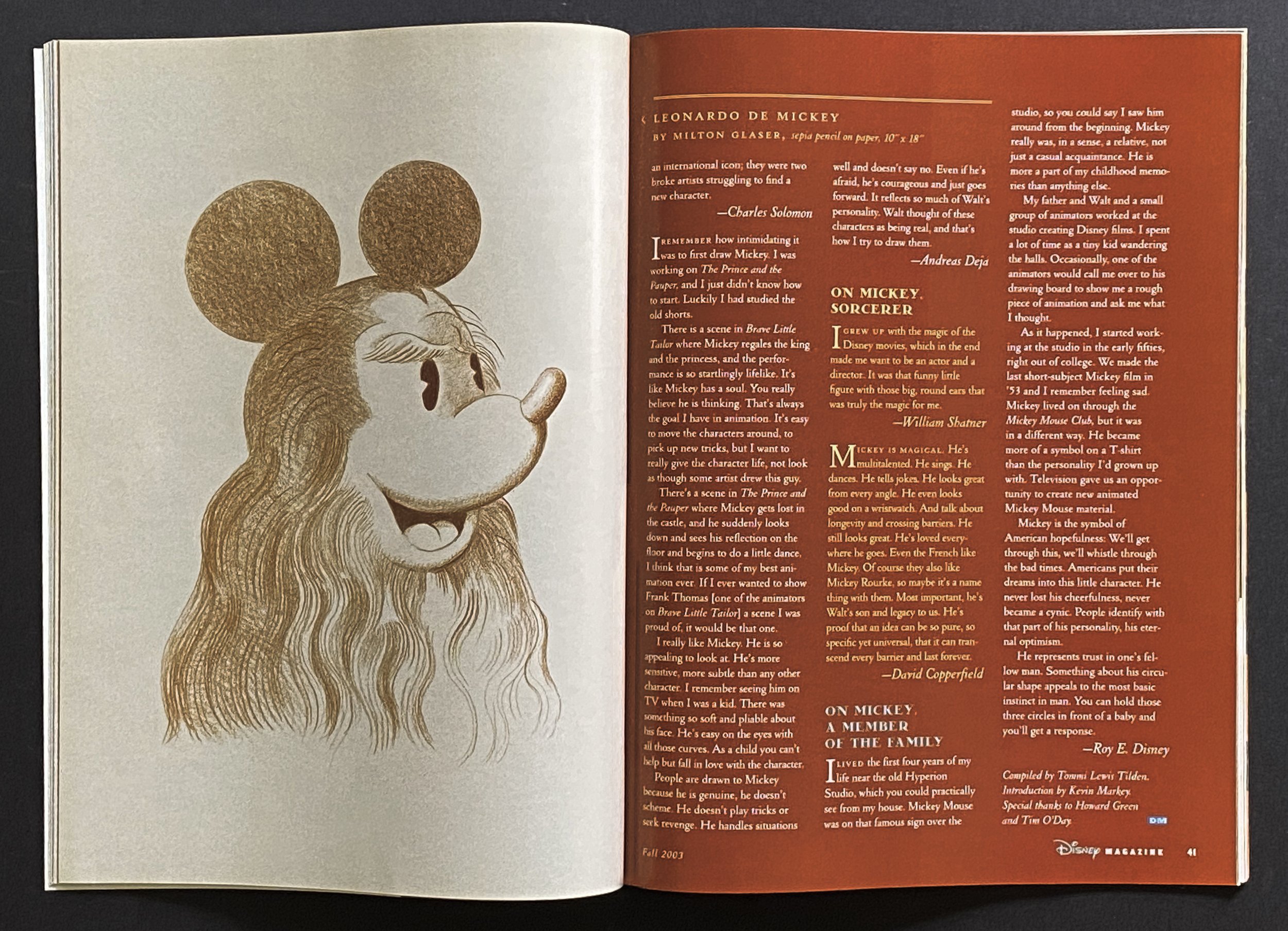

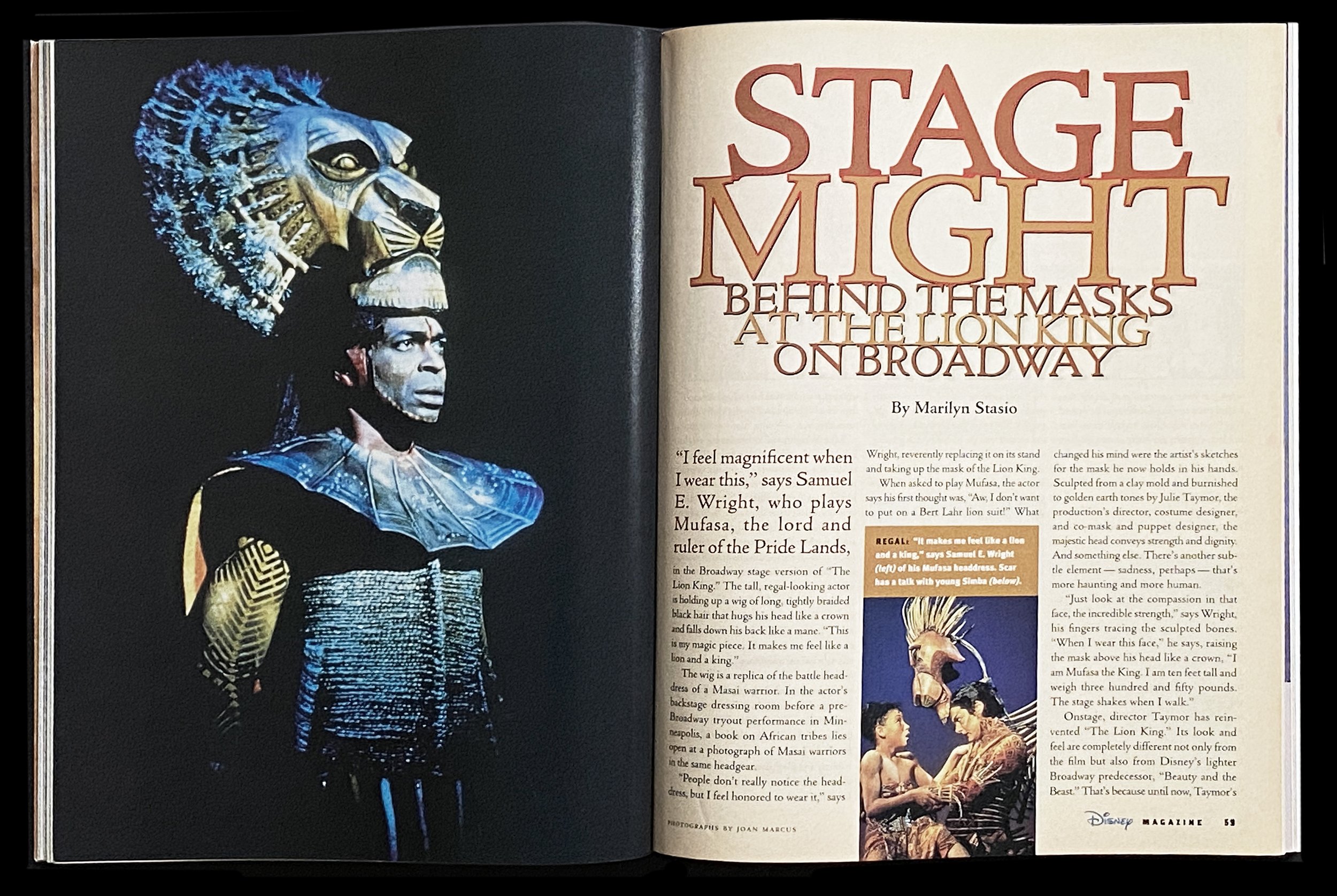

Since 1991, Teensma has been incredibly busy: He was part of a team that built a media empire for Disney, launching and producing Family Fun, Family PC, Wondertime, and Disney Magazine. He’s designed dozens of books and redesigned almost as many magazines. And he continues to lead the creative vision of the critically-acclaimed nature journal Orion.

You might not know Teensma by name, but his network of deep friendships runs the gamut of media business royalty. Why? Because everybody loves Hans.

When they designed the ideal temperament for survival in the magazine business, they might as well have used his DNA. He’s survived a nearly 50-year career thanks to his wicked sense of humor, his deep well of decency, and above all, his unlimited reserves of grace.

You’re gonna love this guy.

The Roundhouse in Northampton, Mass., was the long-time home of Teensma’s design studio, Impress.

Patrick Mitchell: We’re here in South Hadley, Massachusetts, in a restaurant called Thai Place. And I think it’s a, uh … Thai place … right?

Hans Teensma: By every indication, it looks like the place.

Patrick Mitchell: And I thought you might want to say ‘hello’ to our massive Dutch audience, and welcome them to the podcast.

Hans Teensma: Ah, is there a mass audience out there from Holland? Well, goedendag, en dit is Hans, and I’m now going to join all the people born below sea level and wish you a happy day!

Patrick Mitchell: Thank you. So let’s talk about your beginnings, and so maybe you could just kind of rattle off your background, from where you were born, and who your family was, and how you were brought up…

Hans Teensma: Real quickly, I was born at a very early age [laughs], below sea level in Holland, The Hague. Came over at age about ten. Moved to LA. Grew up in Bellflower/Artesia, where all the famous Pixar and Disney people grew up. But I didn’t meet them until too late [laughs].

And I had a very happy childhood in Holland and I do remember many, many wonderful experiences over there. And I think it might have influenced me because I’m just a happy kid. The glass is half full—at the top—which is even more interesting [laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: I have to ask: Did you ever put your finger in a dike [laughs]?

Hans Teensma: No. I, I, I, I think that’s a… . Well, we know that story from long ago. But I … I never was called to action.

Patrick Mitchell: Good, good [laughs].

Famous Dutch boy Hans Brinker, who plugged a leaking dike with his finger.

Hans Teensma: But I do love old Dutch masters and the Dutch graphic designers. And you know, every time I hear the word Dutch, I perk up. So it stayed with me a lot.

Patrick Mitchell: So were you aware of design even at that point. Did that just kind of surround you?

Hans Teensma: I think it did. I mean, as an art director, many art directors that I know, we tried to do everything. We wanted to be illustrators, typographers, photographers. We do everything. And I was doing everything since I was, you know, walking.

Like, you didn’t know the difference between kunst [art] and life. It’s all the same.

And all the Dutch books that I was given and took back with me to America—I grew up with those. And comic books, and the very un-PC comic books from the ’50s.

Patrick Mitchell: Right.

Hans Teensma: And I took every art class that was available. I went to Long Beach State for my university.

Patrick Mitchell: Wait, let me back up. What did your parents do?

Hans Teensma: My dad was an engineer. A technical engineer and a draftsman. He designed Her Majesty’s ships. And when he came over to America he had to switch over to cranes and all kinds of large machines.

Patrick Mitchell: Why did you guys move to the US?

Hans Teensma: I think clearly it was because this was the land of opportunity in 1960. This was the “land of milk and honey.” We had Eisenhower as president, soon to be Kennedy.

Patrick Mitchell: So this wasn’t a transfer. This was a choice to move?

Hans Teensma: Yeah, we were on a list to legally immigrate either to either Brazil or to America. And we got on the list and America came up first. We had some sponsors here who greeted us and we didn’t know what we were gonna do, except this was the “land of opportunities.”

And the Cadillacs had huge fins. And Chevrolet—don’t forget the ’59 Chevy! I mean, things were just, you know, fantastic. And we got all of our dishes and towels and boxes of Tide. It was just … happiness and optimism.

Patrick Mitchell: How big is your family?

Hans Teensma: I have three brothers and a sister, so five all together, and we’re all spread out all over the United States.

Patrick Mitchell: Did any of them choose a creative life?

Hans Teensma: Not in my opinion [laughs]. They’re all very dedicated civil servants. They all wanted to do government work and were real interested in, you know, they love nature and gardening, and weather, and all that stuff. But they’re not artists.

And my mother who was, you know, a huisvrouw [housewife]. She did not know there was anything besides housework. But super optimistic, great sense of humor. And I think that really made me what I am today.

Patrick Mitchell: You said you went to what, Long Beach State?

Hans Teensma: Yeah. University of California at Long Beach. And I had a fantastic professor named George Turnbull. I graduated in ’75. And until he passed last year, I was still in touch with him.

Patrick Mitchell: Wow.

Hans Teensma: He was my mentor. And I went to see him in northern California when he stopped teaching to raise quarter horses, which was another big plus for me.

Teensma’s mentor and a design professor at UC-Long Beach, George Turnbull

Patrick Mitchell: Was it a big design school?

Hans Teensma: The college was really good for graphic design and art. And the department was really substantial. I remember we used to have joint portfolio reviews with Art Center. And Art Center was, you know, really good. Their people were masters. But what we had that Art Center didn’t is all the other classes that you have to attend [at a university]. So our artwork had a lot of context, and content, and stuff to it that they didn’t have.

They had the super skills for art and design, but we had concepts. We took our stuff from philosophy, and Chinese history, and all that kind of stuff and worked it into our work. You know, unconsciously, we just were always thinking of the narrative in design. So I think we excelled from that standpoint.

Patrick Mitchell: What was your major called?

Hans Teensma: I think they just started the BFA program there, so it was just Art. But I took every art class. It took me six years to graduate because I couldn’t say “no” to any class: printmaking, design, illustration, photography, you know, I just didn’t want to leave. I just loved it all.

Patrick Mitchell: Had you at any point that young started to zero in on magazines?

Hans Teensma: No. As a matter of fact, the day I graduated, I moved to the San Francisco Bay area because I didn’t want to get stuck in Los Angeles because I don’t like that much traffic. And that was my goal all along: to get out of LA as soon as I could.

And so I moved to the Bay Area and thought, What am I going to do?

And I pounded the pavement and tried this and that. And about a year later, after working as a graphic designer at a photography studio, I said, “Hey, wait a minute. What I like to do is educate and entertain.” And the only thing I thought of that did that was magazines. I thought, Magazines educate and entertain, and I didn’t want to do advertising, logos, and that kind of stuff.

So I was out bird watching with my good friend, Peter Matthiessen, at the time, and he said, “Hey, there’s a new magazine started by Rolling Stone in San Francisco called Outside. Why don’t you go look?”

And I did. And the timing was perfect. I think I was prepared. I put together a portfolio of all my photographs, all my concepts, all my art, using Letraset [laughs]. And and I put together a portfolio—which I still have to this day—and I walked in there and I lucked out because they had just decided to get rid of their art director. And I took over. And my very first job was paste-up, design, and a week later, art director!

Teensma’s career began at Outside magazine, which was launched by Jann Wenner (pictured above in the original San Francisco office of Rolling Stone and Outside).

Patrick Mitchell: So it’s 1977. You’re in San Francisco, and you are now the art director of Outside magazine …

Hans Teensma: And I couldn’t believe it! I mean, I was 27 years old. I’d never done anything like this before.

Patrick Mitchell: It was probably hard to ignore the fact that you were in the same building as one of the most important magazines in the history of the world?

Hans Teensma: Oh man, that was part of it. You know? I mean it was brick and ferns everywhere [laughs]. And if you saw the movie Almost Famous, you’d realize that was my world.

Patrick Mitchell: So they [Outside and Rolling Stone] shared the office?

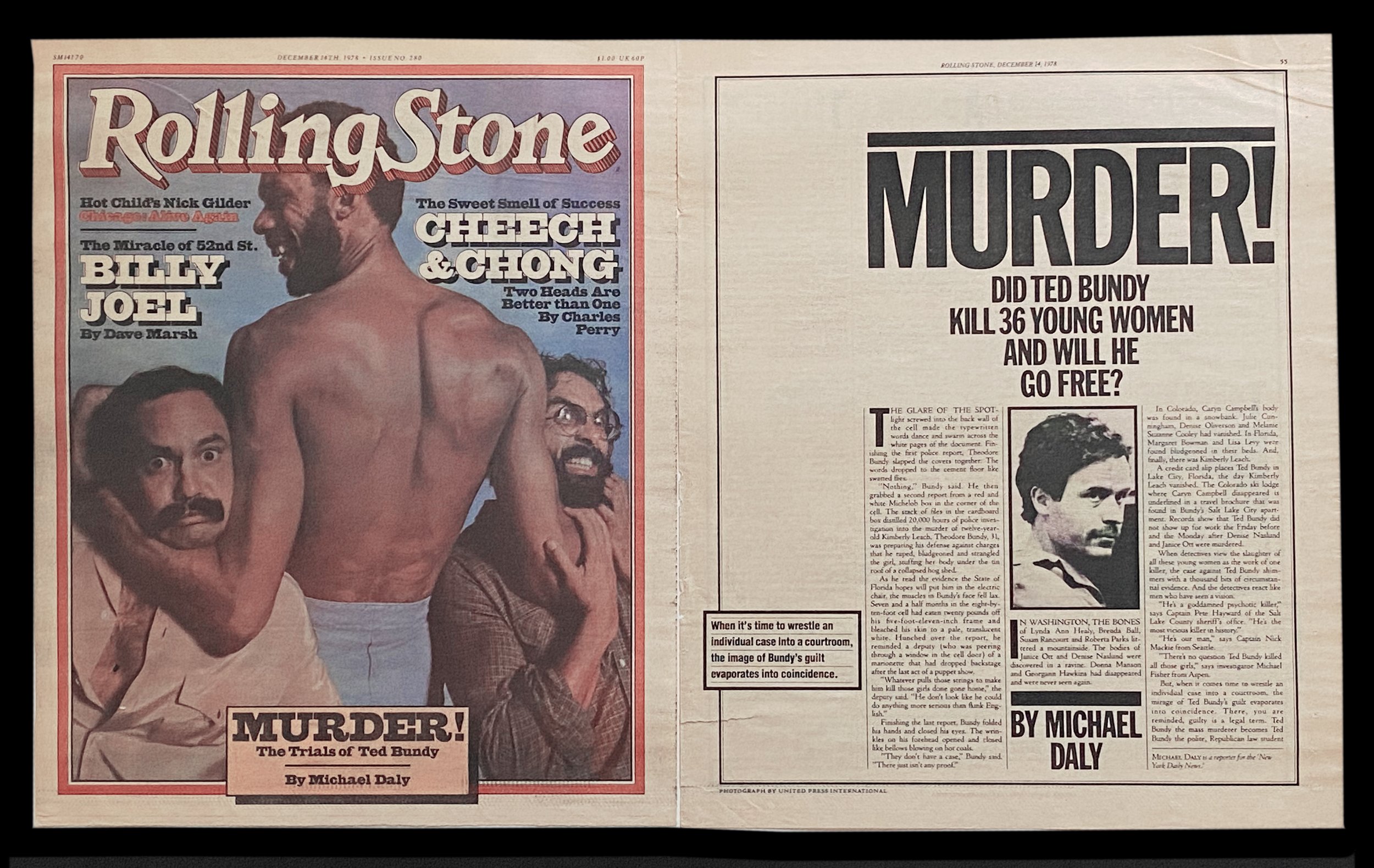

Hans Teensma: [Rolling Stone] had just moved to New York, to Fifth Avenue, next to the GM building.

A Robertson camera

Patrick Mitchell: Was Outside in the old Rolling Stone building?

Hans Teensma: Yes. The old offices. We had this giant Robertson camera. It’s a camera that’s about 40-feet long, that shoots the [page] flats.

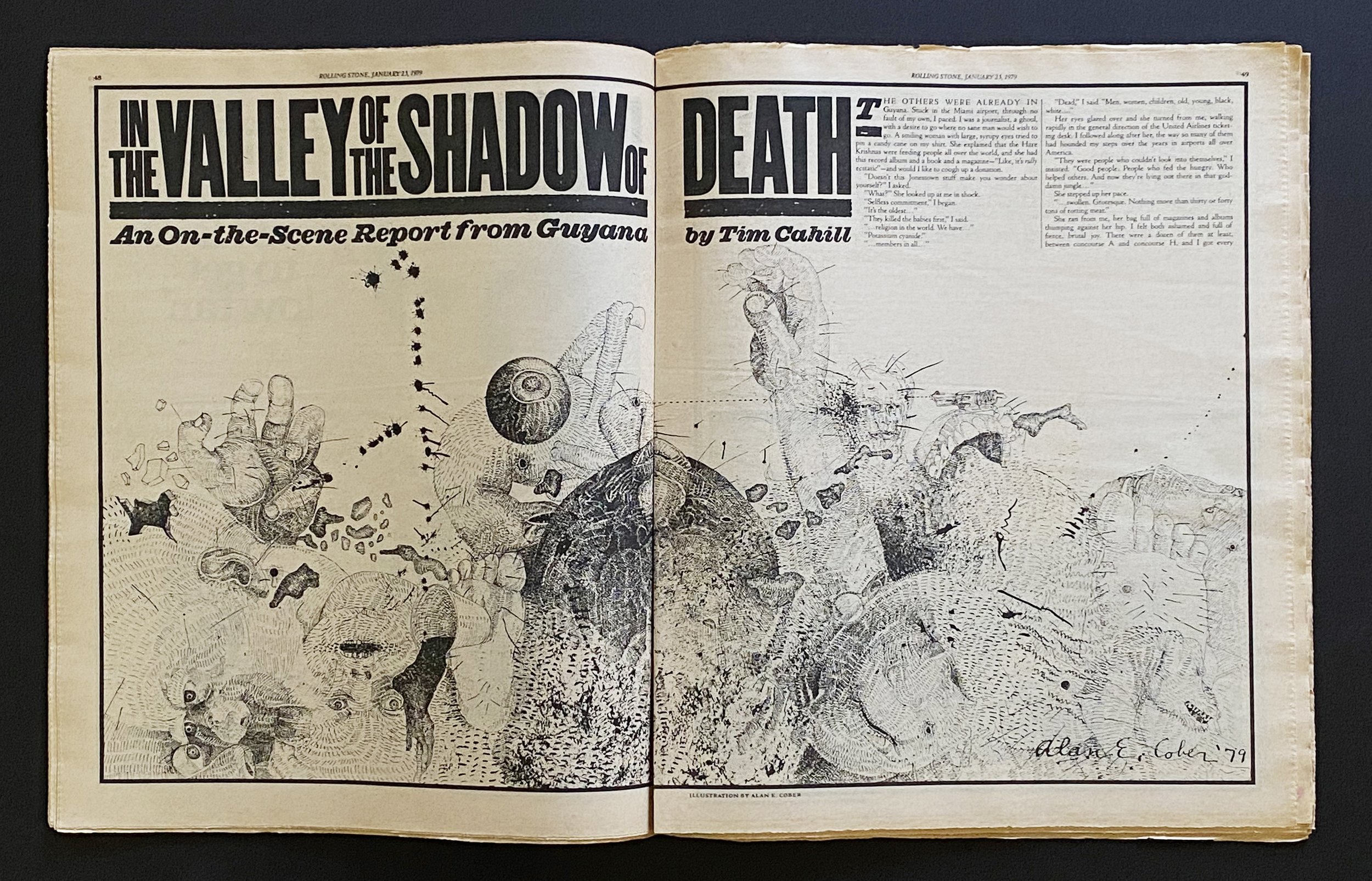

We had Annie Leibovitz’s pictures stuck behind desks and underneath chairs and stuff. We kept finding little bits and pieces of it. We had a few of the leftover editors, Ben Fong-Torres and Tim Cahill, and all those people were still hanging around there. And so we were very aware of it. Plus, they had just invented a new thing called the “Mojo,” which was an early fax machine.

And of course, Roger Black, who was now with Rolling Stone in New York, wanted to see the layouts. And so he would, you know, expect them to be “Mojo’d” to him. And that got old very quickly, but we were so impressed—My God, you can see a layout through the wires within five minutes!

Patrick Mitchell: Was it color?

Hans Teensma: No, black and white. The first “fax.” In 1977. And so we did a number of issues. The editor was Terry McDonell, who was a terrific startup magazine ...

Patrick Mitchell: … Legend …

Hans Teensma: … A legend indeed. And then, the next thing you know, Jann Wenner sold it to Mariah in Chicago, which eventually moved to Santa Fe. And so Outside magazine is one of the few magazines of my 20 magazines that are still living.

The ’70s & ’80s: Outside & Rolling Stone

Patrick Mitchell: How new was it when you got there?

Hans Teensma: Brand new.

Patrick Mitchell: So you were there for Issue One?

Hans Teensma: No, it was maybe Issue Four, but you know, they were just … Virginia Team at CBS Records in Nashville was the ‘official’ art director, but it was still finding its feet. So we were just really starting.

Patrick Mitchell: I remember it back then. Was there a direction from on top to make the design feel related to Rolling Stone?

Hans Teensma: Not at all. No, no.

Patrick Mitchell: So you think it was more “of the time” than of Rolling Stone, that three dimensional style of typography, and fonts?

“We had Annie Leibovitz’s pictures stuck behind desks and underneath chairs and stuff. We kept finding little bits and pieces of it.”

Hans Teensma: Yeah. I brought my fonts and, and you know, Roger definitely liked a few more than others. But, you know, Egizio, I brought into the fold, and a few rule styles, but mostly it was my doing, because typography was my thing at the time—even at that young age and inexperienced—and, you know, I faked my way through the magazine completely because I just knew type. And I knew what I liked.

Patrick Mitchell: Was Outside magazine Jann Wenner’s idea?

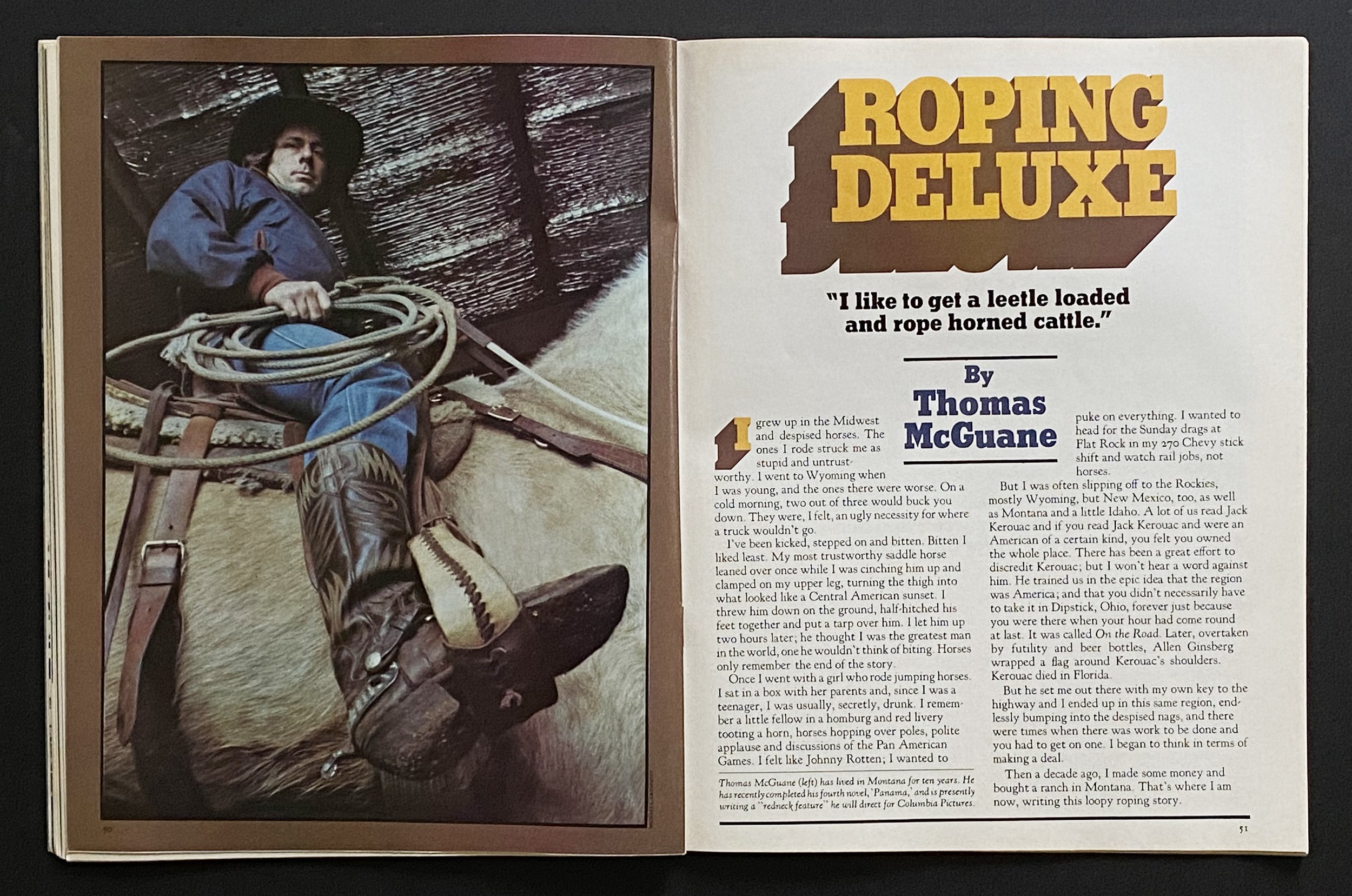

Hans Teensma: Yes and no. It probably had a lot to do with Jann having the resources do something like this. It was a great idea. But my next magazine, which I’ll talk about in a second, was really the forerunner of Outside.

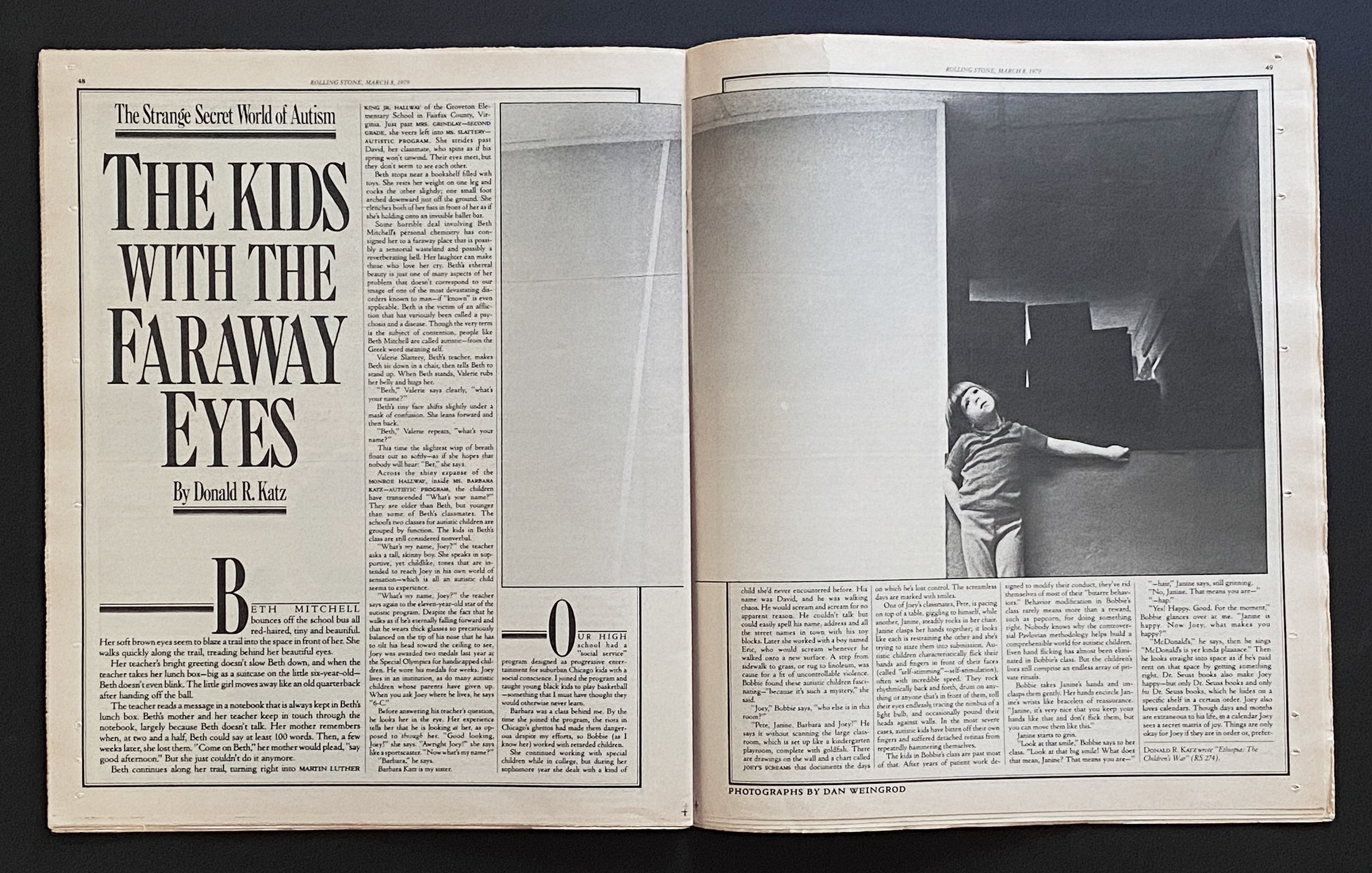

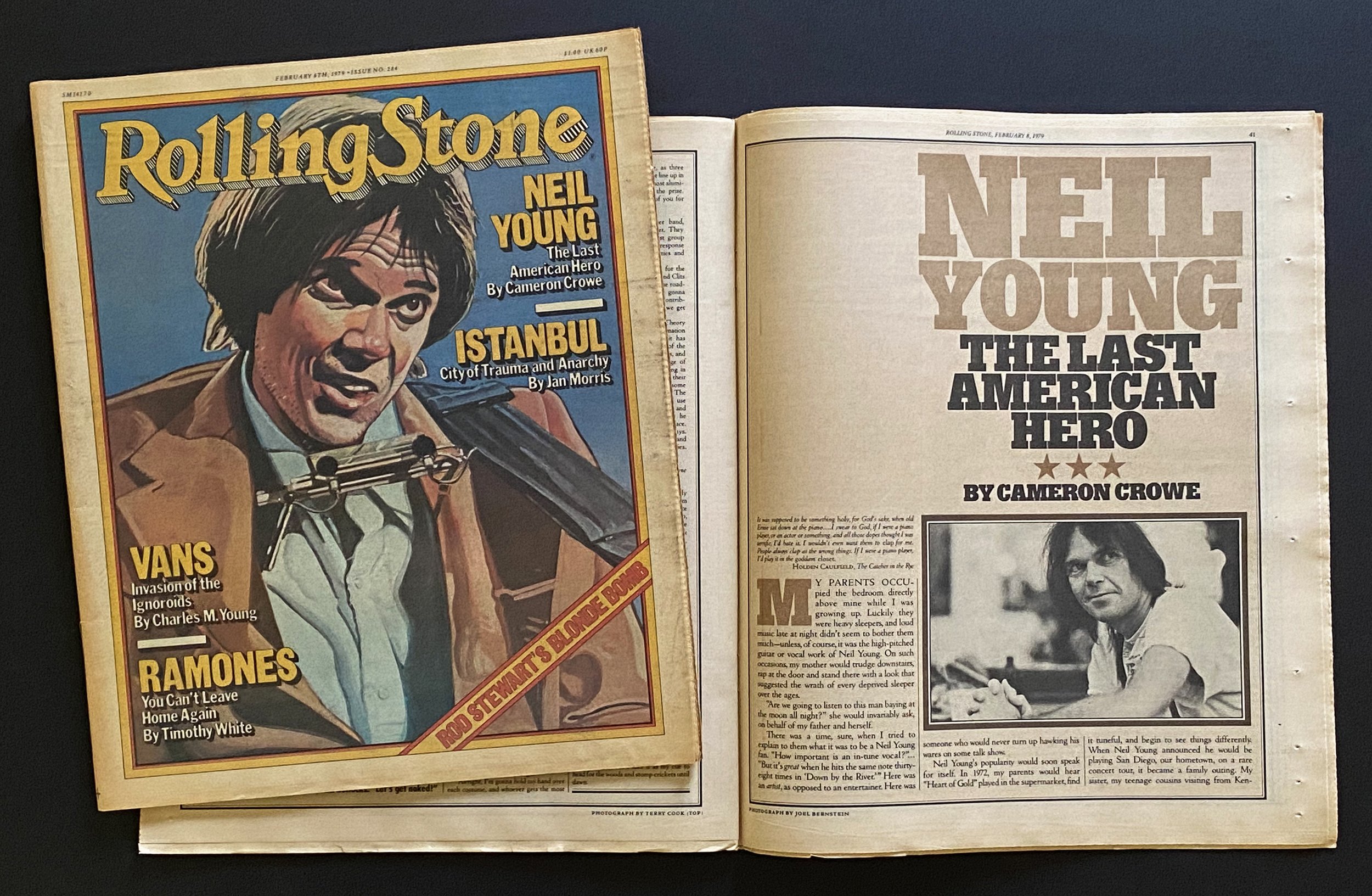

When [Wenner] sold it, Terry and I moved to New York, because it was wasn’t officially sold yet. So we decided to just kind of keep it going in New York. But then we realized soon that it was not gonna go anywhere. He sold it completely. And then I was invited to stay working for Rolling Stone in New York with Mary Shanahan and Greg Scott. So the three of us were designing the magazine at that time.

Patrick Mitchell: How long were you in New York?

Hans Teensma: I was in New York about eight months, just as I was in San Francisco.

So one thing changes after another, and I got an invitation to move to Denver to start a magazine called Rocky Mountain Magazine by a guy named Terry Sieg, who went to Jann Wenner a year before that to try to do a magazine called Outdoor magazine.

And of course, Jann Wenner ended up training the entire staff, and Terry McDonell and I moved to Denver and used several of the people from Outside to quickly launch Rocky Mountain Magazine, which, by the way, also won a National Magazine Award for General Excellence. And it was an edgy magazine never-before-seen in that part of the country, covering the Rocky Mountain states.

The ’80s & ’90s: Rocky Mountain Magazine & New England Monthly

Patrick Mitchell: How long did that one last?

Hans Teensma: Three years.

Patrick Mitchell: And what killed it?

Hans Teensma: Advertising. You know, if you depend on advertising, you’re putting yourself out there. So I didn’t know what to do exactly.

Except then I got a call to apply at Texas Monthly. But one of the editors down there at Texas Monthly Press scotched the deal. And they went with Fred Woodward instead of me. But the next day [that editor] called me and he said, “You wanna move to New England and start a regional magazine called New England Monthly?”

So by that time I knew that I was a migrant magazine designer. I would go wherever there was work, you know? That was great. So then Dan Okrent and I started New England Monthly magazine, and that went for a good eight or nine years before, again, advertising killed the magazine…

Patrick Mitchell: … but it swept up a bunch of awards…

Hans Teensma: Yeah. Got back-to-back National Magazine Awards for General Excellence …

Patrick Mitchell: … spawned incredible talent throughout the magazine world…

Hans Teensma: We got a lot of great writers and artists and contributors and they’d never seen anything like it before. You know, to me, General Excellence is the award that I want to get. Because that means that art, editorial are well married together. It really works out well.

And that was my last regional magazine.

Patrick Mitchell: So around 1990, you find yourself in the foothills of the Berkshires, in this beautiful part of the country, and the magazine that brought you here is gone. You and a bunch of other people were stranded. And you had an inspiration.

Hans Teensma: I quit the magazine.

One of the first jobs I’d ever quit because I really thought, about that time in 1990 that—actually it was more like ’88—that I said, “I wanna do my own thing.” And I’ll consult. And that didn’t last long because nobody wants a consultant.

So they got my associates, Tim Gabor and Mike Grinley, to take over, and they did a great job taking it to the next step. Dan Okrent also left the magazine. And so I started Impress in 1988— the year I got married, at 37—and I thought, Okay, this is gonna be fun.

Patrick Mitchell: Why ‘Impress’?

Hans Teensma: I just love printing. And I just love the double entendre of, I want to make something special, to make something good, and I want to put ink on paper, because I still believe— I still believe forever—that ink should be on paper.

And so we did a few magazines. We did a few redesigns. We got invited to work on People magazine and Newsweek.

Patrick Mitchell: In what way? Redesigns?

Hans Teensma: Redesigns, yeah. But not successful I would say. I mean, when I did Newsweek, Bill Broyles was just named editor. But it didn’t work out for him, so thus it didn’t work out for me.

Patrick Mitchell: But you were dependent on New York for clients?

Hans Teensma: Yeah. I think the magazines all came out of New York and at the time I was doing mostly magazines. I’d done a couple of books with Stuart, Tabori & Chang.

Patrick Mitchell: Was it difficult to convince New York clients that this little studio in the Berkshires could compete with the big guys in New York City? Was that ever a barrier for you, an obstacle?

Hans Teensma: It was, yeah. I think it was a challenge because you know, they’d say, like, “can you be here the next morning?” And I’d have to take a train in. And in ’88, I was taking the train to New York at least once a week. Or driving in.

And gradually they saw that it was possible to come in every now and then. But remember: in those days we were still Xeroxing layouts, pasting them together, sending them via FedEx. And they would see them the next day. The modem, which was, you know new technology… . Apple had just come out and Dan Okrent, who was in New York at the time, and I started a magazine. It was spin-off of Life magazine. I think we called it Our Times, which was the first “young” magazine.

So we would try different things. But they never really got past Issue One.

But I had a low overhead. I’m in New England and I’m enjoying my evenings and it wasn’t a problem at all. You know, just doing freelance work here and there.

Teensma’s business card bears his motto, “To have and to hold.”

Patrick Mitchell: So your new studio, Impress, is up and running, and you’re working with clients around the country and in New York, and then one day your doorbell rings …

Hans Teensma: … and a guy named Jake Weinbaum says, “Hey, you wanna do a magazine about air & space?” And I said, “Sure!” So we went down to DC where he was, and …

Patrick Mitchell: … Jake was an editor at US News [& World Report]?

Hans Teensma: No, he was a marketing guy at US News. But he had an idea for a magazine. At first it was air & space, and that didn’t work. And then it was windsurfing, but I couldn’t stand up straight [laughs], so that didn't work.

And then he had an idea for a family magazine. And so we did a bunch of mockups of a magazine called FamilyFun, which wasn’t my idea for good title, but it said everything. And for the first time, there will be a magazine for how to have fun with the family. Not a bunch of advice.

And that came out of my little, tiny studio in this little village [Williamsburg] in New England. And next thing you knew, we did a big story on Disney. Jake went to Disney with the magazine—and sold it to them! And all of the sudden we had resources.

Patrick Mitchell: By meeting you, Jake stumbled on not only a design studio, but a bunch of editorial talent…

Hans Teensma: …Exactly…

Patrick Mitchell: …that was still in the area from New England Monthly and elsewhere.

Hans Teensma: Right. Exactly. Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: But I don’t guess his initial plan was to start this empire in Northampton.

Hans Teensma: He never intended that. No. I remember him saying many times, “I never thought this was gonna happen, but here I am.” So he’s the one driving from New York. Now he’s in New York working at US News there. And pretty soon he said, “OK, I’ve got a magazine going here. And you know, I’m stuck with Hans, who’s in New England, but he has a lot of friends who know how to make magazines.”

So the thing just kind of started taking off.

Patrick Mitchell: Did he ever move here?

Hans Teensma: Never did. But he got the first cell phone that I’d ever seen...

Patrick Mitchell: … that western Mass. had ever seen!

Hans Teensma: Yeah, it was a big one. But it, you know, it worked almost everywhere, except in my village.

Patrick Mitchell: So they launched with FamilyFun, and at that point, Jake was not connected to Disney. So Disney comes along and buys FamilyFun?

Hans Teensma: Yes. Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: And then he launches a whole publishing division…

Hans Teensma: And then over the next ten years it really took off, you know …

Patrick Mitchell: … and what were some of the things they published?

Hans Teensma: Well, after FamilyFun was running—and we’re talking one million circulation—he started a magazine about computers that became FamilyPC, which was a partnership with Ziff-Davis.

And so one thing leads to another, next thing you know, Jake’s a brilliant magazine mogul and we did a magazine called Wondertime, which part of my staff and the brilliant Carolyn Eckert took over. Plus the editor, Lisa Stiepock and Anne Hallock. And that started taking off. Then they brought Disney Adventures to us, which we thought we could do better than the people in New York. And we had a lot of other ideas there.

Patrick Mitchell: There were a couple other purely just Disney magazines, right? Well, in fact, I I’m totally skipping over how we met, which was when Impress launched. One of your clients was Musician—which was in my neck of the woods in Gloucester. You were consulting on a redesign and had been asked to help them find a new art director. And I had known of you because you were a big deal. And I think I had reached out to you independently of that opportunity. And I think we sort of stayed in touch in the way you could do before social media and other ways.

Hans Teensma: That’s right.

Patrick Mitchell: And, right place, right time, you brought me in to interview for Musician. I got the job, and we got to work together for a couple issues and then, fast forward, but not too much, we had started a kind of a friendship. And at some point, Disney came to you with this idea for a Sunday newspaper magazine called Disney’s BigTime.

Hans Teensma: That’s right.

Patrick Mitchell: And we got a chance to collaborate on that. I would come out here to visit you in Northampton and work on weekends. And then, one other time—this was a bigger thing for me—you got called in to pitch designing Fast Company.

Hans Teensma: Yeah. And you happened to be in town or something [laughs]. You came along with me for fun!

Patrick Mitchell: You invited me, but maybe you just needed a ride [laughs]. I don’t know. But you brought me into that meeting. And I got to meet Bill Taylor and Alan Webber, the founders. And this was before they launched. They had no funding and they were interviewing design firms to help them create their prototype. But we didn’t get it. Roger Black got it. But that was another opportunity for us to work together. And then a year later they actually had launched, they had money, and they hired me and started my career.

Hans Teensma: You made a great impression on them and I’ll never forget the way they kept looking at you when I was trying to get their attention [laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: All right, so we’re back at Impress. Your studio’s up and running. You’re, I don't know, maybe scarily reliant on Disney for a big chunk of your business. In other words, if they were to leave, what happens? But one of these magazines was Disney magazine—what was the distribution model? Was it a newsstand magazine?

Hans Teensma: Yeah. Mostly bought on the newsstand. They had over 500,000 circulation, which was real substantial for them, but their model was really growth. And if you aren’t growing 20%, ten isn’t good enough. So we couldn’t believe that they would pull the plug after nine years of doing a 500,000 circulation magazine.

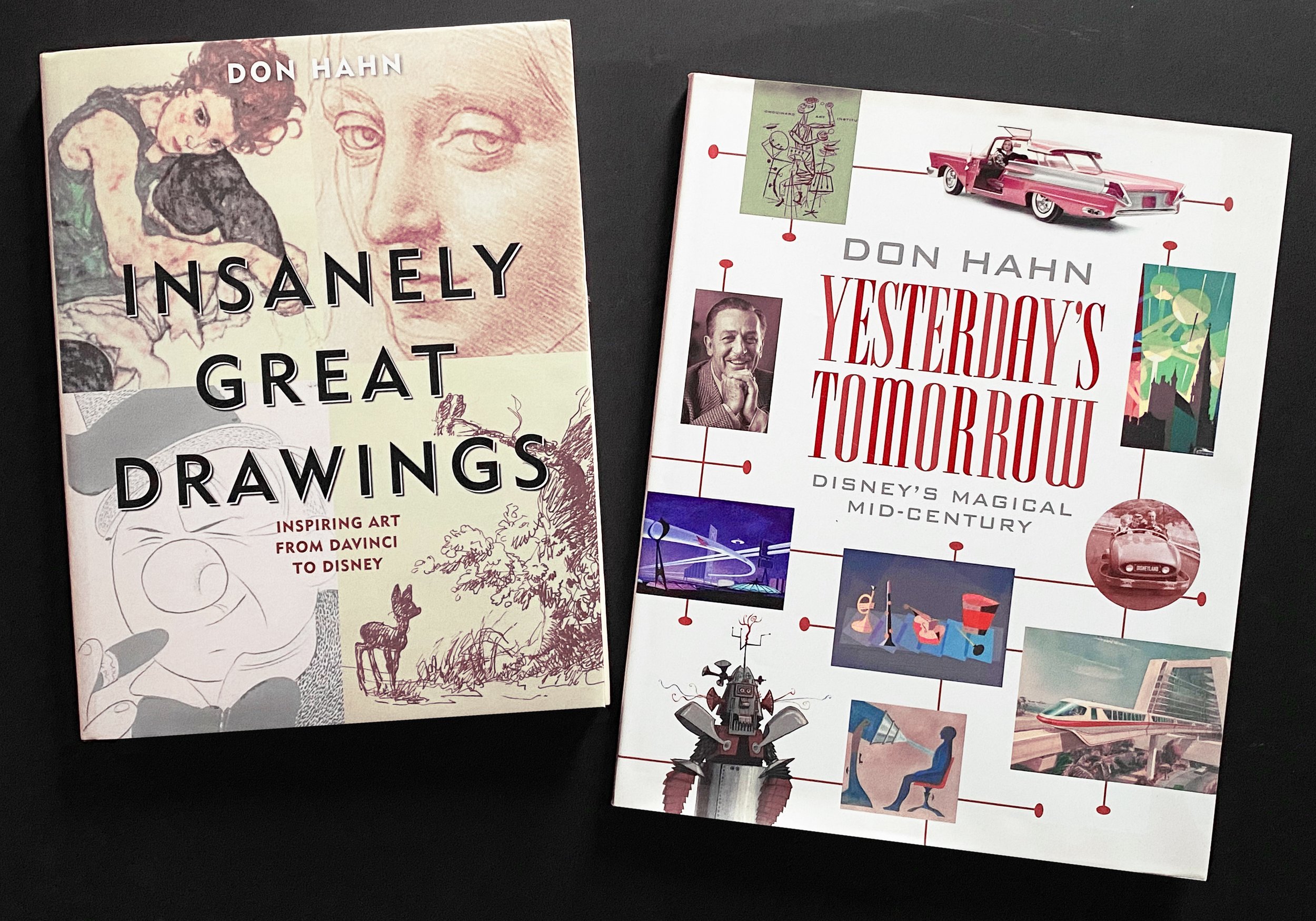

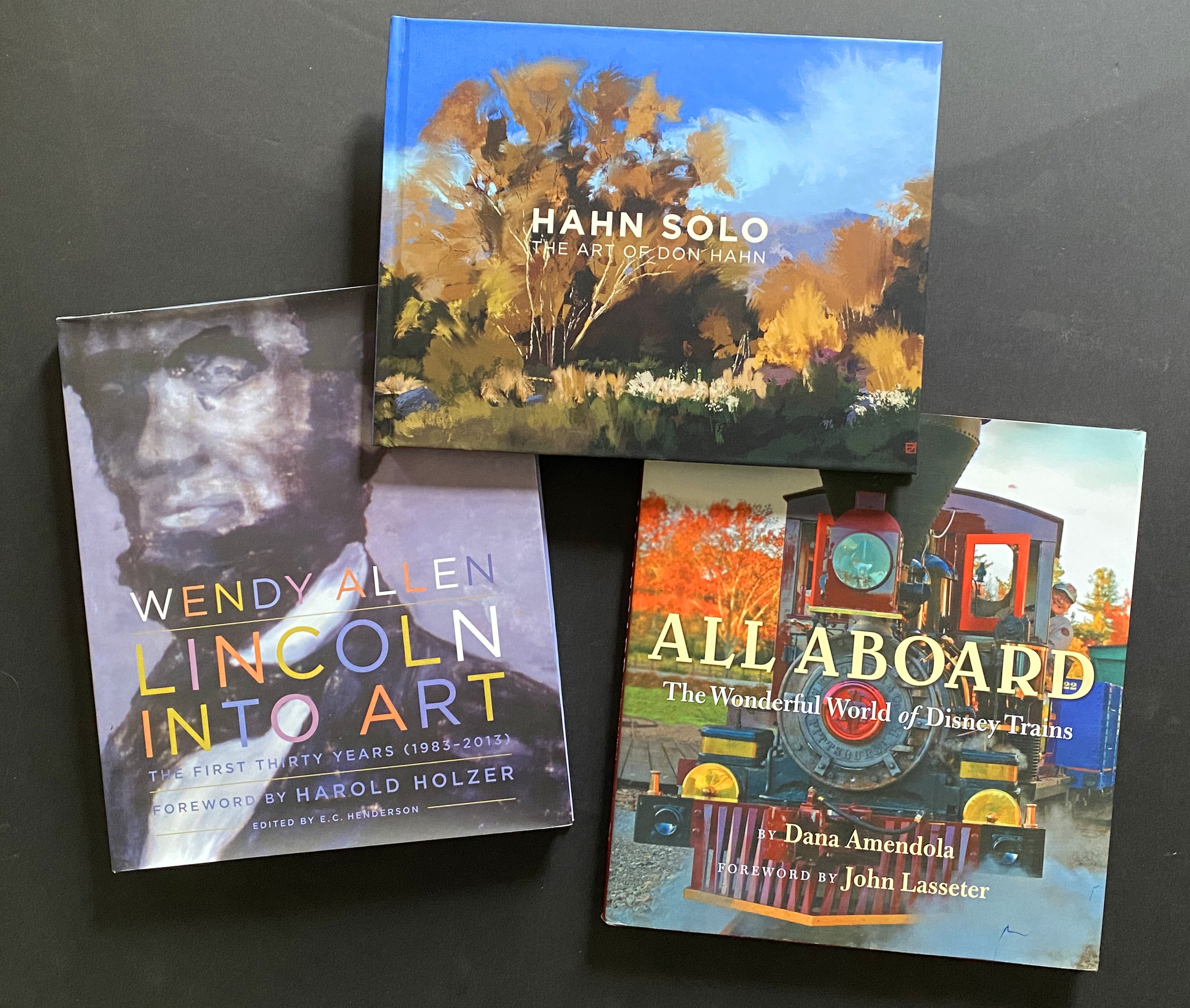

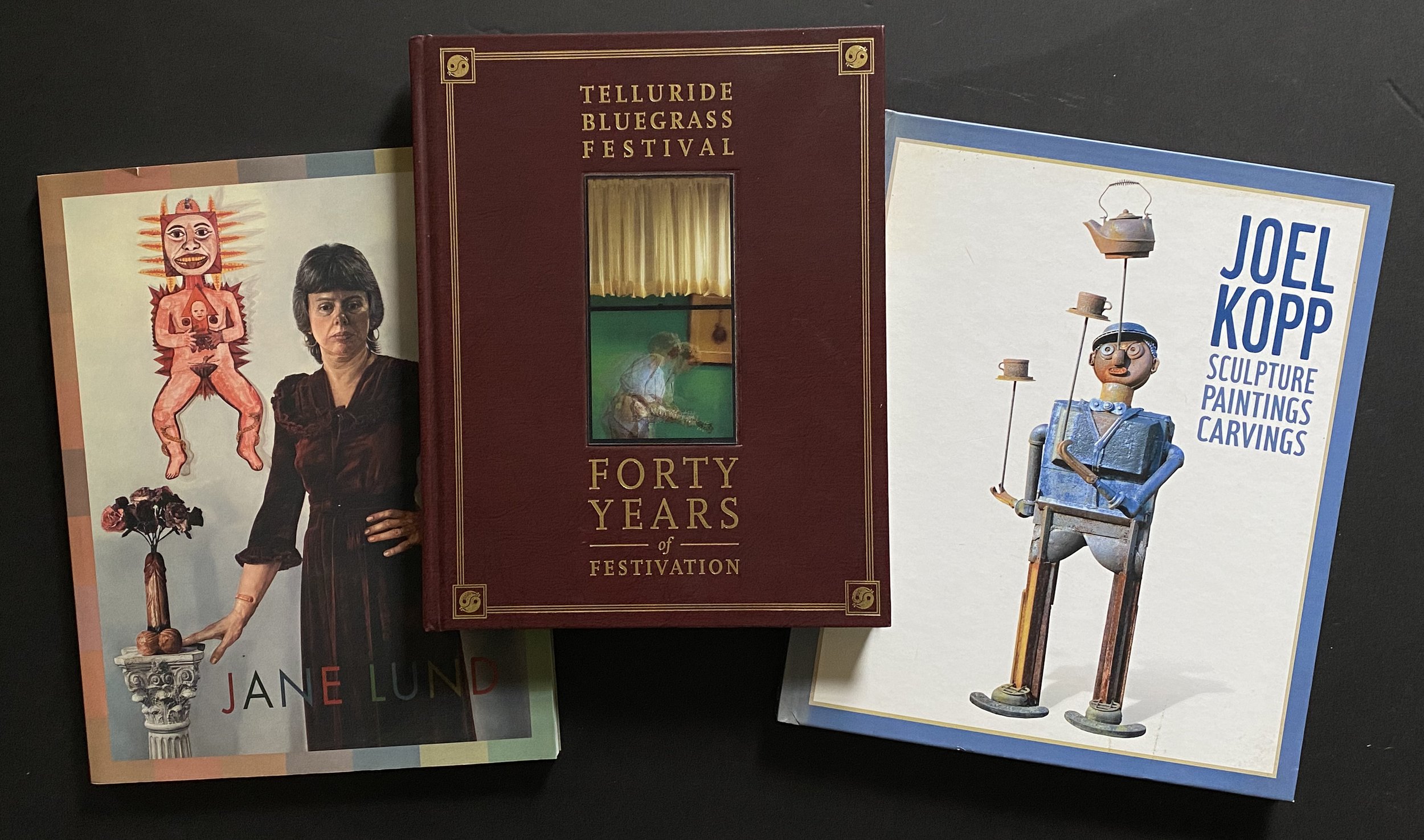

However, with James McDonald and I, and a really good staff, we were able to start doing other books for Disney Editions. And I made some really great friends at the studio and at Pixar, with Don Hahn and Pete Docter, who have continued … and Wendy Lefkon at Disney Editions. So I continue to do big books for Disney. Big animation books with a vast landscape of art. And, to this day, I’m still doing a lot of books with them.

The 2000s: Disney

Patrick Mitchell: So at this point, you’re doing one magazine regularly and 90% books? Really, books is your business now.

Hans Teensma: Yeah, yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: And Instagram!

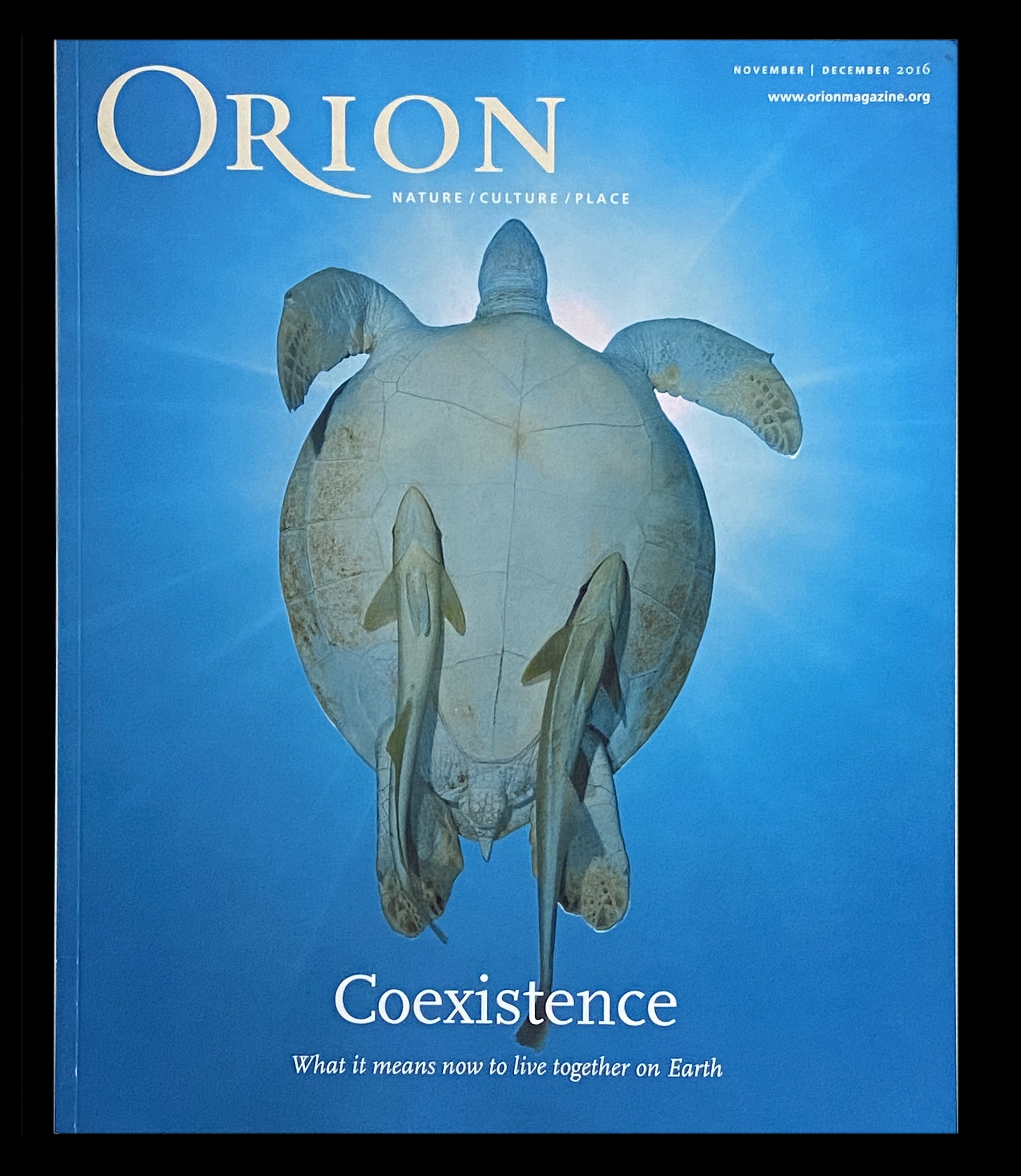

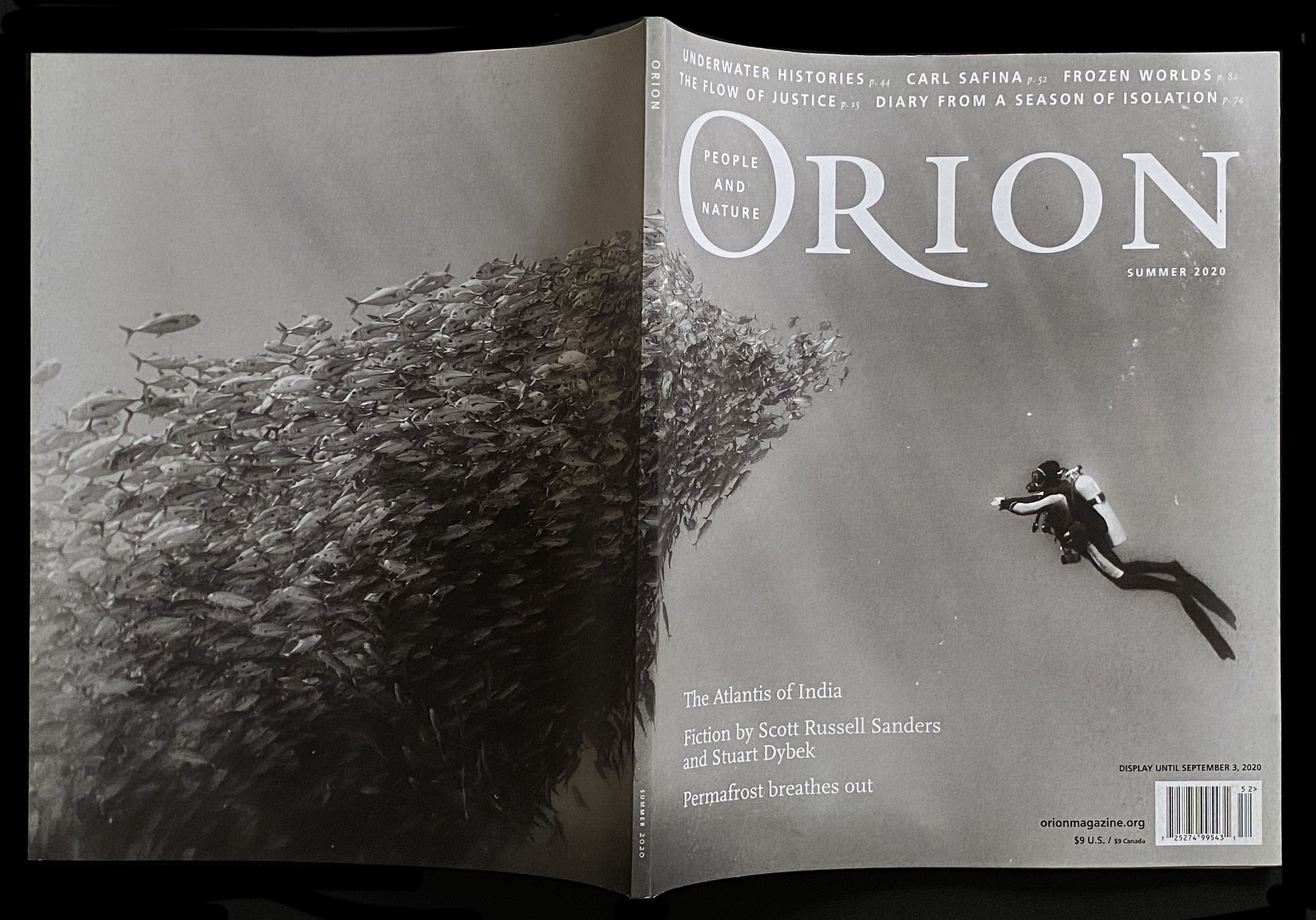

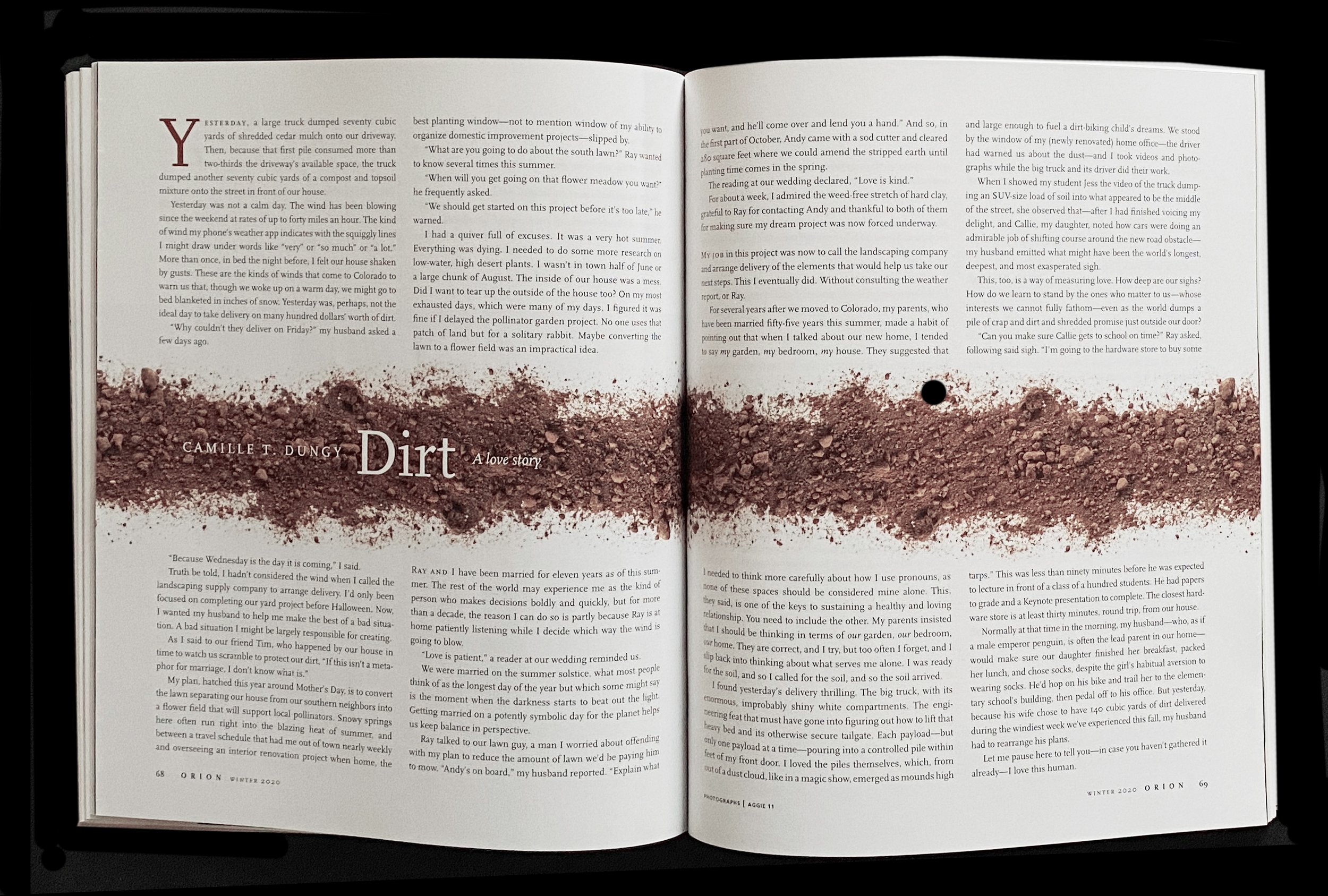

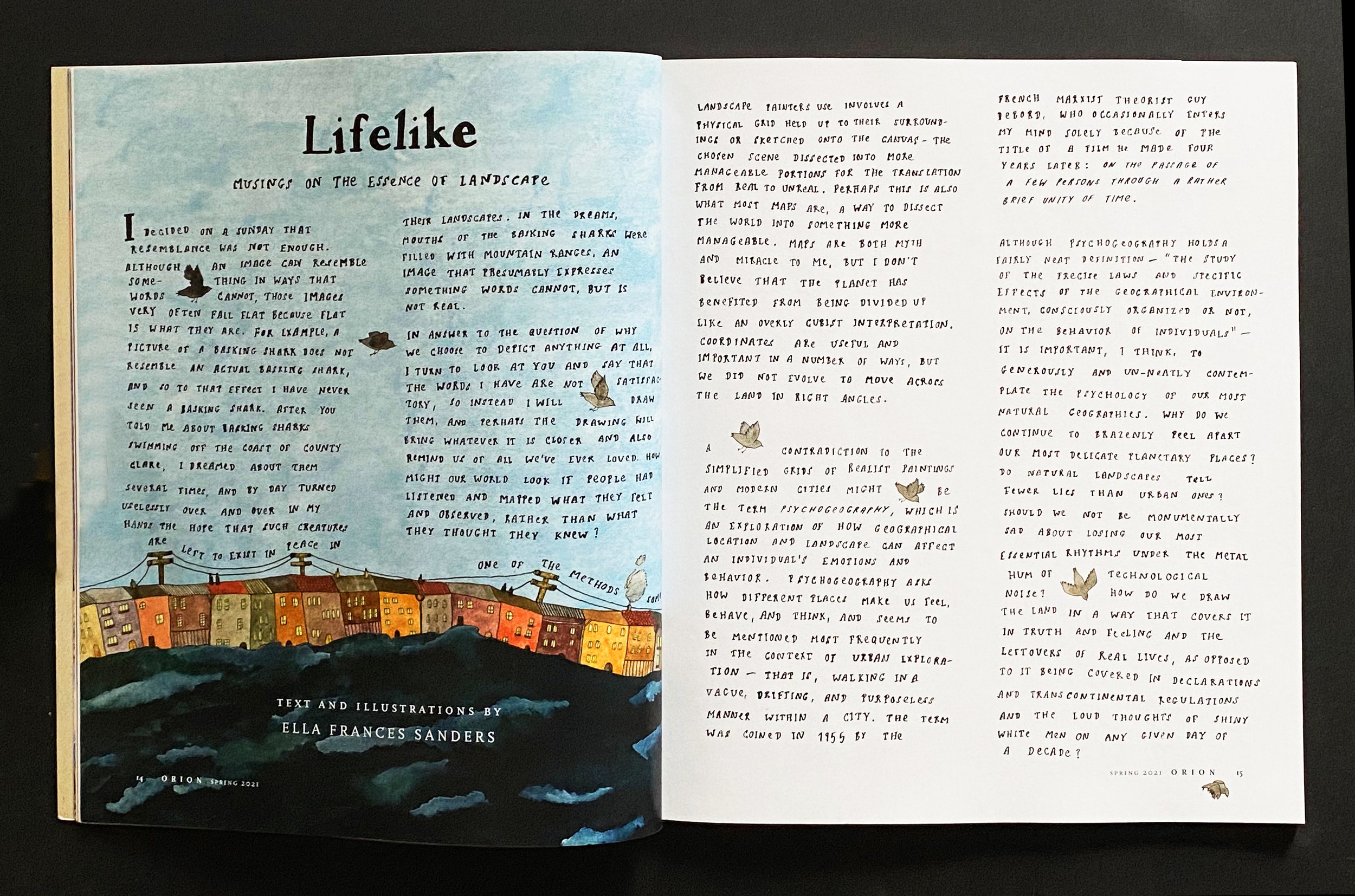

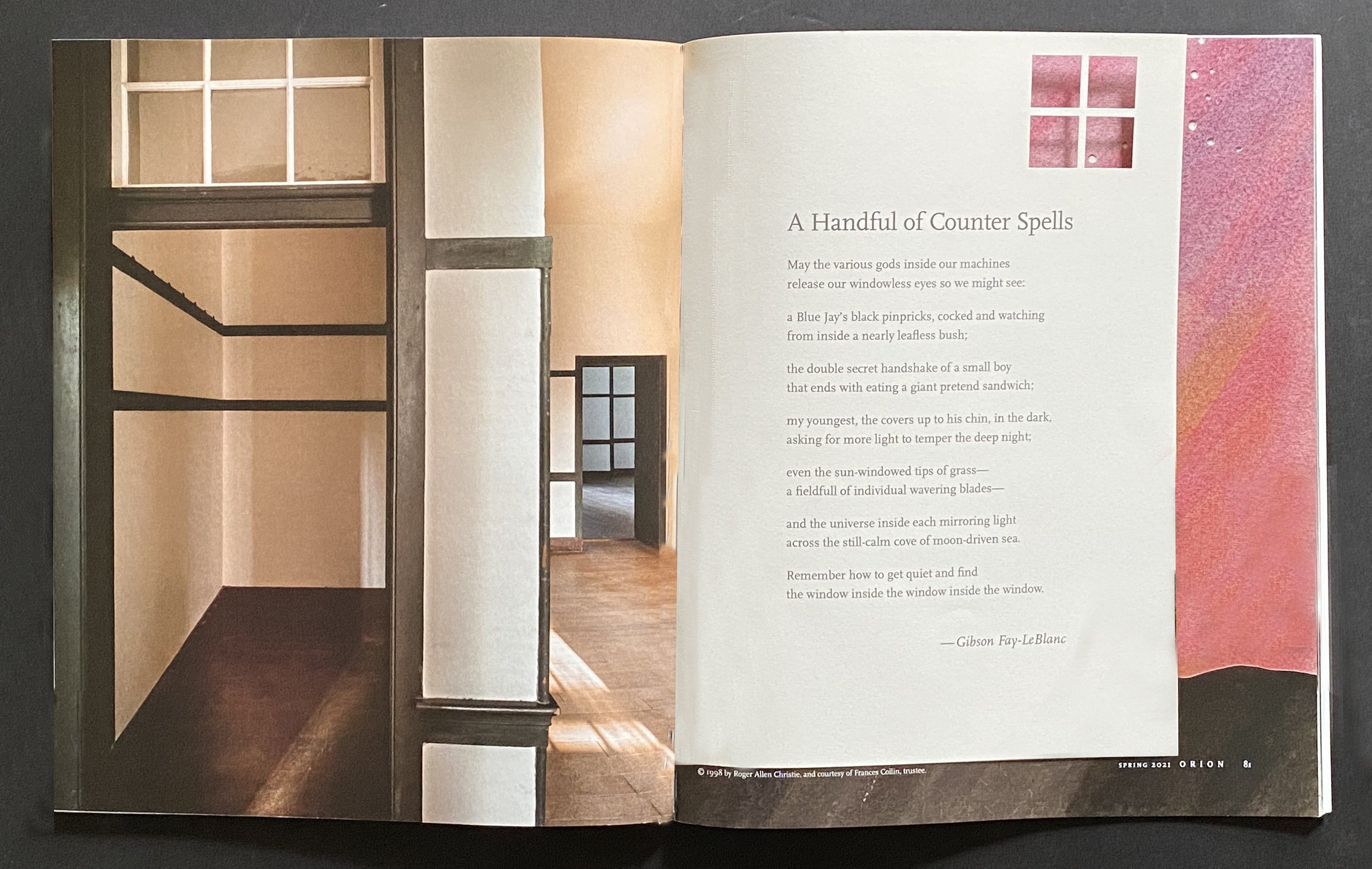

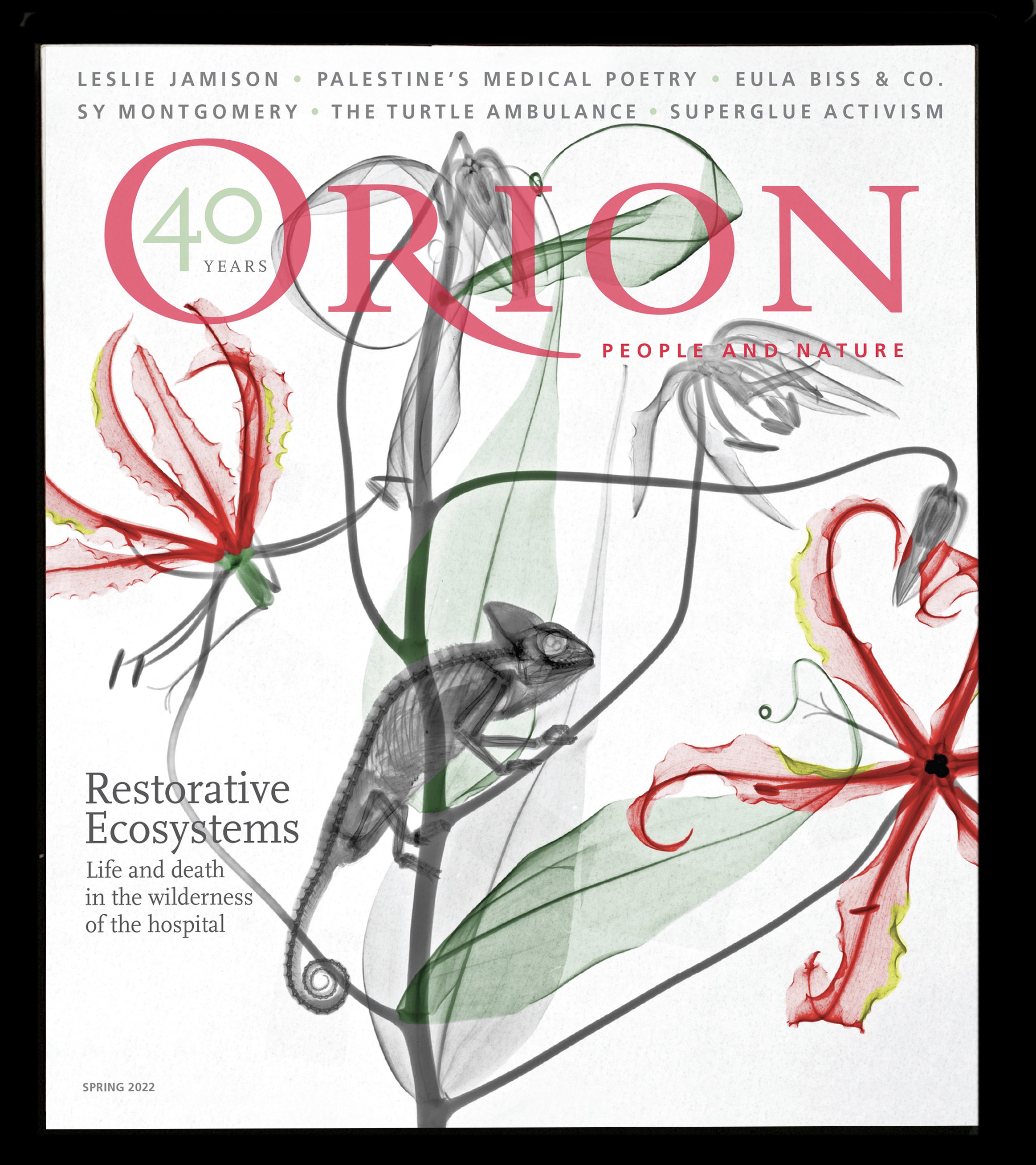

Hans Teensma: I forgot to mention that. I do love that. That’s my toy, but I forgot to mention that somewhere along the line, I was asked to do Orion magazine, which I’m still doing now, 21-22 years later. And that’s a quarterly. It was six times a year, now it’s quarterly. With no advertising.

They’re not dependent on the ups and downs of advertisers. So that’s still around. Lots of art, lots of pictures.

Patrick Mitchell: Is it dear to you? Does it occupy a special place?

Hans Teensma: Yes, yes, yes. It is everything I believe. I believe in interesting art, interesting stories, stories that make a difference.

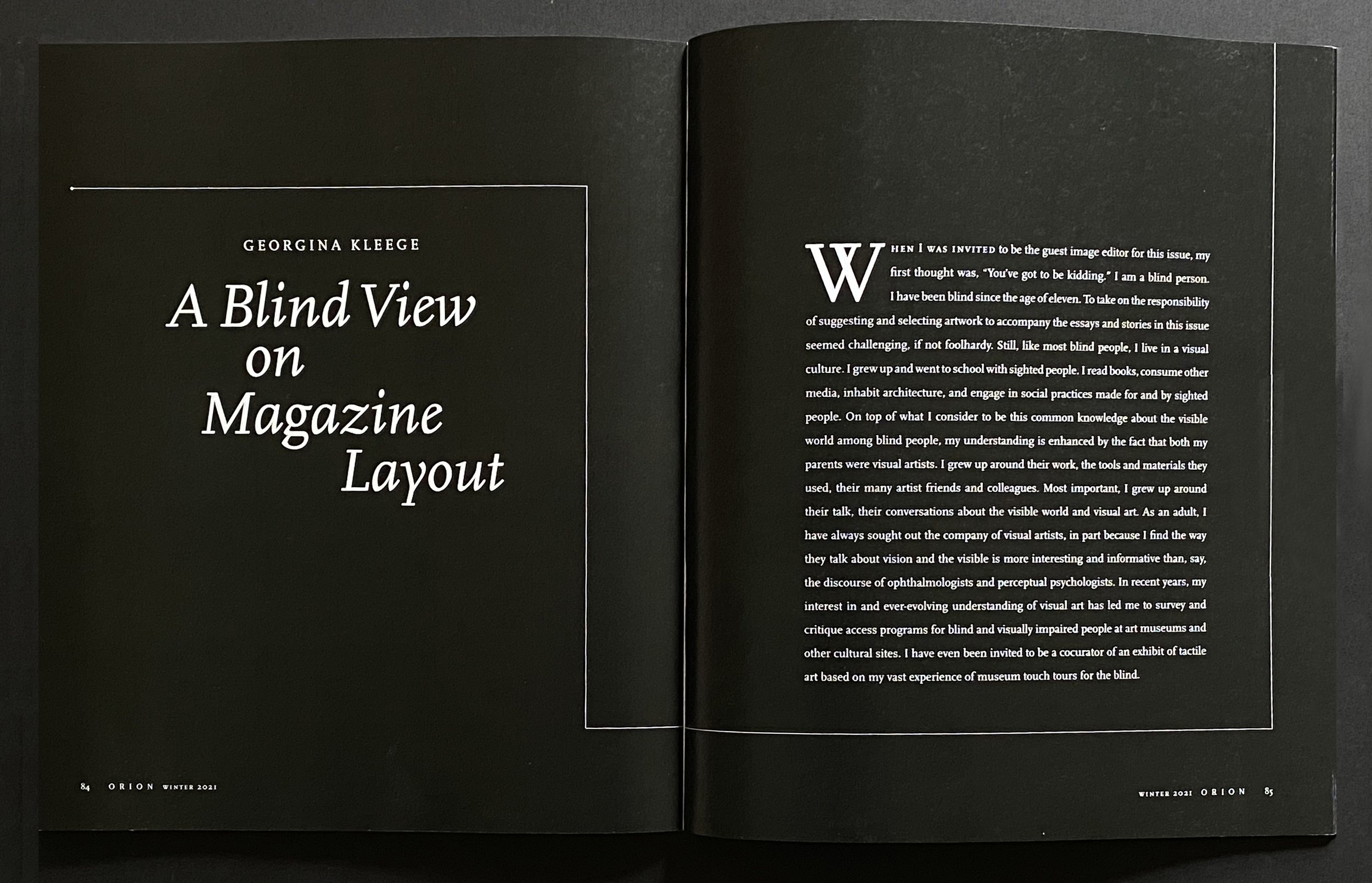

Patrick Mitchell: Just for the listeners, what is Orion magazine?

Hans Teensma: Well, it’s a magazine, that kind of heals the fractured relationship between nature and people, that, you know, with art, poetry, culture, you can actually celebrate nature in a very practical way. And also it aspires to getting people to relate to the natural world and help sustain it. So, more than ever, almost every year since then, it’s more important to keep that one going. And I really do love the magazine. You know, I would probably do that if I didn’t need a job.

Patrick Mitchell: Is print dead?

Hans Teensma: I do not think print is dead.

Patrick Mitchell: Orion seems to agree with you.

Hans Teensma: Well, for a while, Orion was headed toward a digital-only edition. And I said, “are you sure you wanna do this?” Because, you know, my philosophy, my business card says “to have and hold,” you can’t have and hold something that’s digital. And the audience I know is a little more conservative—and conservation is their thing. They do like to, you know, curl up and read a magazine from beginning to end, and touch it, and relate to it, and get back to it, and keep it.

And I think there’s a great place for Orion blogs online and so forth. But I don’t think that one’s going to go anywhere. And I think that’s a good example of why we need a printed magazine.

Patrick Mitchell: Does your business card really say, “to have and hold”?

Hans Teensma: It does, yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: I did not know that. That’s a great line. So, you’re obviously still inspired about what you do. What inspires you about print?

Hans Teensma: I think I just love to see things and know that they’re gonna be there when I turn off the light and put it down. I like to write on it. I like to touch it. I like to stick it on the shelf and put it on my desk to have and hold, as I said, is my philosophy and on my business card. I was the first person to buy an iPad when it came out, because I really think it’s a terrific interactive kind of thing. And I love my iPhone, even if it is mostly a camera for me.

But I do think that print isn’t going anywhere. I’ve seen a lot of bookstores close. Borders closed, everything closed. And yet I go to Barnes & Noble, and I go to the magazine section, and I find myself there for an hour, just picking things up, flipping through them. And I know it’s more vertical than it was in past days. The content was more horizontal, but there’s something for everybody there. And I’m a firm believer—I will be the last person to say print is dead.

Patrick Mitchell: So you’ve made it clear: You’re dedicated to print. However, you find yourself at this stage in your life as what we call an “Instagram Influencer.” A late-in-life, Instagram Influencer.

Hans Teensma: Yeah.

Hans Teensma: A man for all seasons.

Patrick Mitchell: The reason we’re here today, in western Mass., is that I came to see Hans’ show at the Readywipe Gallery, a funky little space in downtown Holyoke, Mass. Why don’t you tell me a little bit about this show? It was really incredible.

Hans Teensma: Well, it’s a good topic, the theme being print and digital. Here I am, you know, being invited about three years ago to join the Instagram community. I don’t like Facebook, or “The Facebook” as I call it, because it’s too much of a black hole. I get sucked into it. But I love the idea of “a picture a day,” or a picture every other day, that kind of tells a thousand words. Or maybe it’s up to 1500 now [laughs]? But it’s a beautiful way to relate to something you’ve seen that’s interesting.

As my colleague, Moira Greto, says, it’s in between times during the day, or as my other colleague Carolyn Eckert, who was the aforementioned art director of Wondertime, says, it’s a moment to capture something special, unique, emotional, graphic—one of them.

And we thought, well, this is great. You know, we’re posting it. We like each other. We just kind of continue to … to me, it’s a puppet show where I can entertain people. Going back to 1977 “to educate and entertain”—although it’s more entertainment than education.

And then all of a sudden somebody said, Why don’t you have a show? Would you like to have a show at this gallery? And all of a sudden we are finding ourselves printing these little, ethereal squares into these 12x12 giclées, on archival paper, with archival inks, and people are coming to see it with lights on it. And they’re holding…

Patrick Mitchell: …All shot on iPhone?

Hans Teensma: All shot on iPhone. Yeah. Everything was an iPhone 6 or 7.

And people are walking around with little cheese plates and wine saying, “Oh, look, what’s the artist thinking here?”

“Well, I was thinking, This is a long drive. This is a beautiful icy storm. I think I’ll take a picture of it.”

And all of a sudden we realized that print is not dead. These Instagram ethereal pictures have a whole new life on the wall. And although, you know, we put up about 200 of them. We were not, you know, we’re not selling them. We’re not making a living on them. They’re just to entertain and enjoy. But we do have about two years worth of Christmas presents now they give out to people [laughs]!

Patrick Mitchell: Well, I have to say that I find your Instagram very inspiring because I mean, I’m jealous because I wish I could spend the amount of time that you appear to be spending on it. It’s so good. I mean, given, you know, you’re not shooting what you ate today. You’ve got a concept, and you make short films, and you make beautiful photos, and there’s always a story. It’s a continuation of what you’ve spent your entire career doing. And to see it in that the context of an art gallery with your colleagues was, I don’t know. I mean, on the one hand, none of you profess to be artists in that way. And yet in that context, you’re really great artists. These Instagram feeds are incredible. So I don’t know if that’s your future, but I hope I hope it is.

Hans Teensma: I think it’ll remain my future, because mostly since I graduated or since I was a boy growing up at home, I just love what I do. If I didn’t have to make a living, I’d still be doing the exact same thing. I’d be making a magazine to educate and entertain. And I would be making books because I love books. I love ‘to have and hold.’ And I would be taking pictures, you know?

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah.

Hans Teensma: I mean, when the iPhone 21 comes out, I’m going to be the first one there taking pictures and entertaining people, you know?

Patrick Mitchell: Well, for all of you wannabe influencers, check out @hteensma on Instagram. You won’t be sorry. And hopefully you learn a thing or two.

A classic, obsessive Teensma Instagram video project: “For the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing in July, 2019, I wanted to bring three of my passions forward: space exploration, Lego bricks, and Instagram videos. Every day for one week, I posted a one-minute clip of the progress. With my alter ego, Index Finger, I scored a simple/fun GarageBand soundtrack for each segment. This is a composite of the daily events leading up to the landing. It’s nothing special, but it made me happy to see smiles on faces when viewers saw the pieces coming together, the lift-off, and cinematic feat coming from my desk.”

Patrick Mitchell: So I have a little set of rapid fire questions, and we’ll just go right into it. Number one: What is your favorite color?

Hans Teensma: Well, it used to be the rainbow, but that’s too cliche. So now I’m gonna say it’s just PMS405.

Patrick Mitchell: All right. Look that one up people. Who is, or are, your mentors?

Hans Teensma: Well, the guy that taught me in ’74-75, George Turnbull, who raised quarter horses. He’s still the voice in my head that says, when I finish a layout, he says, “What if?” And I’m going, “Oh yeah: What if?” So he’s still the one.

Patrick Mitchell: Favorite band?

Hans Teensma: That has to be The Beatles. Yeah. And the song is “Flying,” because it’s such a goofy, crazy song where they don’t even have any words. I just love how imaginative they were.

Patrick Mitchell: Did you see the movie Yesterday?

Hans Teensma: I was gonna see it tomorrow. [laughs]

Patrick Mitchell: Favorite font?

Hans Teensma: Scala Serif.

Patrick Mitchell: This is an important question to me because it’s how I define myself. I’m definitely a “journey” person. But are you “destination” or “journey”?

Hans Teensma: I am a “journey” person. Yeah. I love the route, no matter where it goes …

Patrick Mitchell: … Even if the route makes you forget what the destination was [laughs]?

Hans Teensma: Especially! Especially. Yes. Yeah [laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: Coffee or tea?

Hans Teensma: Coffee.

Patrick Mitchell: How?

Hans Teensma: With milk. Lots of milk.

Patrick Mitchell: Coke or Pepsi?

Hans Teensma: I hate ’em both good. Yeah. Green tea with honey.

Patrick Mitchell: Are you a morning person or a night person?

Hans Teensma: The night is so infinite. I’m never done. So I guess I’m a night person.

Patrick Mitchell: Do you have any particular philosophy about that? I mean, I’m a night person and I swear by it.

Hans Teensma: No, I find myself very, very perked up in the morning, but usually it’s the birds that wake me up because I’m still working.

Patrick Mitchell: Laptop or desktop?

Hans Teensma: My laptop is my desktop. I don’t even know because I plug it into a big monitor. I could never work on a small monitor.

Patrick Mitchell: Serif or sans?

Hans Teensma: I love serif. Serif is my thing. Which makes sans even more exciting when you do use it once in a while.

Now: Orion

Patrick Mitchell: A few years ago, I came out to visit you—I think it was a fall day—it was kind of wet and rainy. You took me out to see the labyrinth that you’ve built. And years later, now I’m way more into hiking and out in the woods more, and I’ve started thinking about your labyrinth, which is very well-documented on your Instagram. And I wanted to ask you, I know this is a super-important thing to you and, at the time, it just kind of went over my head. But now with my new appreciation for nature, I kind of wanted to get your take on where it came from, how you named it, what it’s purpose is. So tell us about how it got started.

Hans Teensma: Well, I’m a nature lover. And I don’t like lawns, pretty much because it’s not of much use to most animals and critters. So I just started mowing it in interesting ways. I just started mowing it with the land and the plants that were popping up around me. I just kind of let them grow. So it kind of designed itself. And now after 15 years or so, it’s over my head in most places. Lots of bushes popped up. Crabapples. And I just kind of trim it here and there. And it becomes my morning and evening walk almost every day. Year ’round, snow or no snow.

And it’s—talk about the journey—it really, it just clears my mind. I mean I just, I long to walk and be surprised and it’s not a traditional shape. It’s very meandering and it continues. So you never know when you’ve started and ended. And to me, it’s life.

Patrick Mitchell: So what started as something to spice up your mowing—at what point did it get a named?

Hans Teensma: Well, I was excited to let my dear friends walk it. And when my mother was getting very old and I decided to take her to Holland once, she came out from LA. And she walked the labyrinth and I was so touched that the woman I’ve known longer than anyone was impressed and saw the need for such a meandering walk. I just named it after her. Her name is Henny, or Hendrika. So it became Hendrika's Labyrinth. And so I celebrate that every year on her birthday. It’s June 5, and that’s when it officially opens each year for a whole bunch of people to come over and just walk it.

And one of my joys is to sit on my porch and watch the neighborhood kids running through it, you know, because you can appreciate it all different levels.

Patrick Mitchell: There is a way out, right [laughs]?

Hans Teensma: There’s always a way out.

Patrick Mitchell: All the kids are accounted for [laughs]?

Hans Teensma: Yes, I do have three or four emergency exits in case you panic. But I love it when I actually panic. And I forget where I am—my mind is all over the place or nowhere. And you know a clearing of mind is a very healthy thing to do every now and then. And I really think, oh dear, am I lost?

Here’s a 60-second tour of Hendrika’s Labyrinth

Patrick Mitchell: Has this become like, you can’t live a day without walking the labyrinth?

Hans Teensma: I’m not happy if I don’t walk it.

Patrick Mitchell: Is it a slow process? Do you stop and notice things and…

Hans Teensma: It’s always different. That’s what’s wonderful about it. You know, sometimes I’m thinking about a book that I’m designing. Sometimes I’m thinking about my children or my wonderful wife, Lynne Bertrand. But sometimes it’s just absolutely clear. Sometimes it’s about, you know, a Bald-faced Wasp that’s aggravating me.

And one time I found a deer sleeping in it. And a snapping turtle. It always surprises me—it clears the mind. It’s wonderful. It’s … the human condition.

Patrick Mitchell: It’s like meditation.

Hans Teensma: It’s like meditation and it’s like exercise too, because you’re moving left, right—it’s very organic. As I said, it’s 300 yards and it continues, so you can walk it for an hour, or two hours, or 10 minutes if you want. I don’t have a large backyard, but that to me is … it’s an infinite walk.

Patrick Mitchell: And it can be solemn or social?

Hans Teensma: Absolutely. Yes. And it usually is [laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: And then you have a ‘throne’ in the middle of it—the tower.

Hans Teensma: Oh yes, yes, yes. I decided that I needed a place where I could sit and just kind of observe it all and, silly as it is. It’s built around this elm tree. My friend Carolyn had suggested that I put it there, and I go up there all the time, and I just see animals that don’t expect a human being to be sitting up in the tower. That's what’s great about the Labyrinth—that it’s constantly changing and that’s why it’s a metaphor of life.

Books

Patrick Mitchell: So you’re 71. You’ve had a full and rich career that continues. You’re out here in this beautiful part of the country in a beautiful town. You’ve got the perfect studio, that’s attached to your house. What’s a perfect day for you?

Hans Teensma: Well, a perfect day would be waking up, having coffee with my wife on the back porch, observing the labyrinth, taking care of the little morning necessities before I go out and wander it by myself, then I decide what to do that day.

I usually like to accomplish five things and there’s usually a couple of deadlines, and I’d include a trip to the library, which I can walk to from the house. And then I go to work and I take a break in the middle of the day. I might go to the labyrinth again, trim a few leaves, design something, fax something [laughs]. Oh no, we don’t do that anymore.

And then, on the perfect day, my kids would come home from wherever they are and they would have dinner with us, probably on the back porch or nearby. And, if the moon is full, I might go out and walk the labyrinth one more time. And then around midnight, I decide to stop working and cozy up and hit the sack.

Patrick Mitchell: I really appreciate you doing this. Thanks for getting together with me. Thanks for letting me see your show before that the show ends.

Hans Teensma: Well, thank you. I just really admire our friendship, finding you in Detroit, the Musician magazine days. It’s been a highlight of my life and I really hope that we continue to inspire each other and do stuff like this. So let let’s just say it never ends.

You can learn more about Teensma at his website, but even better, follow him on Instagram @hteensma, and spend some time scrolling there. You’re gonna find some real gems. Teensma’s wife, author Lynne Bertrand, has just published her first novel, City of the Uncommon Thief. Her previous books, all picture books, include Granite Baby, a Booklist Editors’ Choice, and One Day, Two Dragons, a New York Times Editors’ Pick. Bertrand’s affinity for Young Adult fiction prompted this novel, for, as she says, “to be 13, 15, 17 is to be human times 10. It’s a time of unprotected freedom, death, work, love. A good place for a writer."