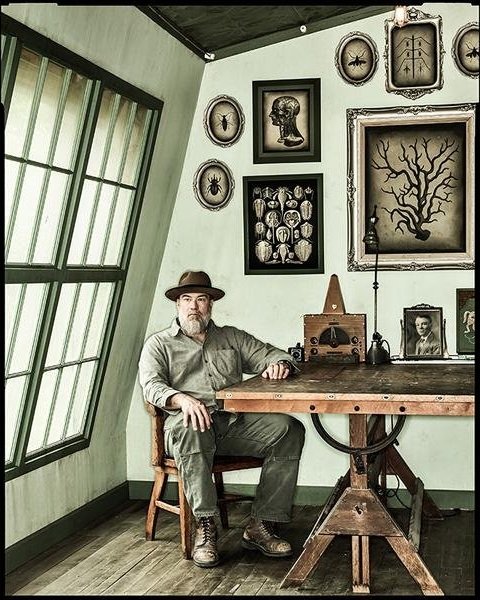

A Handy Man

A conversation with photographer Dan Winters (The New York Times, Rolling Stone, Texas Monthly, Wired, more).

President Barack Obama for New York magazine

Photographers are gearheads. They’re always throwing around brand names, model numbers, product specs.

So when legendary photographer Eddie Adams asked today’s guest, Dan Winters, if he knew how to handle a JD-450, it was a no-brainer. He had grown up with a JD-350. So yeah, the 450 would be no problem.

But here’s the funny thing: the JD-450 is not made by Nikon. Or Canon. Or Fuji. Or Leica. Not even his beloved Hasselblad. Nope. The JD-450 isn’t made in Tokyo, Wetzlar, or Gothenburg.

The John Deere 450 bulldozer is made in Dubuque, Iowa, USA.

And what Eddie Adams urgently needed, right at that moment, was someone to backfill, level, and compact a trench at his farm, which, coincidentally, was prepping to host the first-ever Eddie Adams Workshop, the world-renowned photojournalism seminar, at his retreat in Sullivan County, New York, near the site of the 1969 Woodstock music festival.

Get to know Dan Winters a little bit, and none of this will come as a surprise to you. It also won’t surprise you that the bulldozer incident isn’t even the funniest part of the story of how Winters got to New York City in 1988 to launch what has become one of the most distinguished careers in the history of editorial photography—a career that began with his first job at the News-Record, a 35,000-circulation newspaper in Thousand Oaks, California.

The secret—spoiler alert—to his remarkable career, Winters will say, “is based in a belief that I’m being very thorough with my pursuits and being very realistic. I’m not lying to myself about the effort I’m putting into it. Because this is not a casual pursuit at all. This is 100 percent commitment.”

Well, that, and out-of-this-world talent and vision.

Ryan Gosling for Wired

George Gendron: So it’s 1988. The magazine industry is really thriving, especially in New York City. And you’re a photographer for the Thousand Oaks Chronicle.

Dan Winters: Uh-huh. The News-Chronicle of Thousand Oaks.

George Gendron: Yeah. And I want to hear you tell the story, which I think is really remarkable, about how you made your way from there to New York City, via Eddie Adams’ farm. And don’t leave any details out: the missing portfolio, the uncle who isn’t there…

Dan Winters: Wow. Okay. You want to hear the whole thing.

George Gendron: I want to hear the whole thing [laughs].

Dan Winters: Okay. I was working at the Thousand Oaks News-Chronicle, which was a 35,000-circulation daily. We had seven staff photographers, a full-time lab tech, full-time photo editor. You know, I still hold it to be, probably, one of the greatest times in my life.

I had a ’62 Volkswagen bug and my David Hume Kennerly Banana Republic photojournalist vest and a couple of Canon F-1s around my neck. And I was just absolutely in heaven doing general assignment work. My mentor, John Gray, who was an instructor at Moorpark College, he called me and he said, “Hey, Eddie Adams and Kodak and Nikon are throwing an event called the Eddie Adams Workshop in upstate New York. I think you should apply.” I said okay. He gave me the materials and at the time it was all mail. So I mailed 20 transparencies. They were all copy slides.

George Gendron: Let me jump in. Remind people who Eddie Adams was, and his significance, and his reputation at that point.

Dan Winters: Eddie Adams was a photojournalist best known, in my opinion, for his coverage of the Vietnam war. Most significantly, the photograph of the street execution of the Viet Cong prisoner by General [Nguyen Ngoc] Loan, who, at the time, was the chief of police in Saigon. The photograph immediately went viral and was reproduced extensively the world over. In combination with that image and the photograph that Nick Ut took of the “napalm girl” running from the village, naked—those two images, I think, really weighed heavily on the public consciousness and support of the Vietnam War. I think they were kind of the beginning of the end.

In Eddie Adams memorable photo from the Vietnam War, Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan (left), chief of the South Vietnamese national police, executes a Viet Cong prisoner on a Saigon street during the Tet offensive in 1968. Adams reported that after the shooting, Loan approached him and said, “They killed many of my people, and yours too,” then walked away.

Eddie had a career after that. He started doing Parade magazine covers and much more slick, studio stuff. He kind of always imagined an environment that could foster young talent that was solely merit-based. It was based on review of work, not an interview. Nothing else. It was based on 20 slides. And at the time it was available to applicants that had two years or less professional work.

I applied and kind of forgot about it, to be honest with you, because it seemed like the application processing took a very long time, but I got a letter in the mail, and I’d been accepted to the first year, and that was a hundred students from all over the world. I had never been to New York and I was beyond excited about it.

At the time I was at the paper, I was thinking very, very strongly about magazine work. I was looking at all the magazines. I was looking at what Sports Illustrated was doing, what Fortune was doing. A lot of the stuff that Gregory Heisler was doing at the time and really fashioning a lot of my newspaper work in that manner. I was taking lights to assignments and doing portraits that were lit, and I was shooting 4x5. I really had my sights on doing magazines. So I went to the workshop and I lost my portfolio … somehow. So I had no work to show.

George Gendron: [Laughs] I don’t mean to laugh. [Laughs again].

Dan Winters: Yeah, no, it’s actually funny, now. I had made arrangements to stay with my Uncle Bill, who was, at the time, the head of world public relations for General Motors. He had a very big job in the General Motors building on the park. I had communicated with him and told him exactly when I was coming, et cetera, and he was totally fine with it. And I showed up in New York and first off, tried to figure out how to track down my portfolio in a cab, which is the most naïve thing probably ever. But I had no idea. I started calling cab companies and asking if they’d found a black box. It was just a debacle.

I got to my uncle’s house and rang the buzzer and I didn’t get an answer. So I waited a little while, went and got something to eat. Went back, kept buzzing, nothing, nothing, nothing. I ended up spending the night in the—he lived in a brownstone on 82nd street on Central Park East. I ended up sleeping in the flowerbed area of his—and this is October—of his place …

“What are you doing right now? Okay, here’s what you do: Quit your job and move to New York.”

George Gendron: … Welcome to New York!

Dan Winters: Yeah, right! The next morning, I just decided I was going to buzz all the buzzers in the building. I got the super, and I explained that I was Bill Winters’ nephew, and he actually had a contact number for Bill whenever he would go anywhere. He’s in Detroit at the time. He called Bill. And of course I got the thumbs up, so I had an apartment after that for the two days, and I have a loaner car from him as well.

So I drove up—this is, like, a comedy of errors because I also drove up to the workshop thinking it started on a Friday, but it started on a Saturday [laughs]. So I got up really early on Friday and drove up there and I pulled into the farm and it was just this absolute beehive of activity.

People were trying to get everything prepped. They still didn’t have—they’d just hooked up the power to the barn. But they were overwhelmed and there was a trench that went from the barn of Eddie’s farm, which is where the workshop is being held, to the road, which was several hundred yards. And I kind of assessed the situation and I asked someone—I said, “Is there anything I can do to help? I’m here early, accidentally. I’m one of the students.” And they said, “You know how to drive a bulldozer?” And I said, “Yeah, I do.” We had a JD-350 growing up and you guys have a JD-450. I can totally drive the bulldozer. And they said, “Can you backfill that trench?” The trench went from the barn to the road, a couple hundred yards. And I said, “Absolutely.”

So I got on it, and several hours later I had it back-filled, leveled, and compacted. And Eddie, I saw him a couple of times standing around, in his black gear from head-to-toe, with his black hat, and his black pants, his black shoes, and his black shirt. I saw him watching me a few times while I was working. And when I was finished I saw him and I went up to him and I introduced myself and he said, “Listen, I want you to come to the farmhouse every night.”

So, “coming to the farmhouse” meant that you got to go into this wonderful environment where all of the instructors sat sipping whiskey and sharing stories. I remember Carl Mydans talking about shooting [General Douglas] MacArthur coming ashore onto Leyte [in the Philippines]. It was just this amazing magic.

That’s the first time I met Nick, by the way. And it was just this incredible experience. I was the only student in there. And, for whatever reason, I talked to the folks at the workshop, I spoke at the 20th anniversary and the 25th anniversary. I spoke to the folks there that had been involved in it that entire time. And they said in the entire 25 years of the workshop, not one student has ever been allowed in the house. I was the only student that’s ever been allowed in the house at night. And I thought, Well, that’s a pretty cool little achievement.

So anyway, at the workshop—since I didn’t have any work to show and everybody else had work to show—I convinced someone that they should dig through the files and pull my 20 slides that I submitted, so that I’d have something to show. I felt like I already had quite a bit of juice because of the whole bulldozer thing. So they did. They went and found it and gave it to me. So I had something at least at night because there’s a really wonderful … First of all, the environment there was really, really wonderful and conducive to creative talk and creativity in general and the exchange of ideas, et cetera.

Ridley Scott for Wired

And every night, ancillary to the workshop, is this informal portfolio review. A number of the many instructors and speakers would make themselves available to students to look at work and have an exchange about it. It was very informal. It wasn’t scheduled. You waited around the table.

If you wanted Jay Maisel, or you wanted Greg Heisler or Mary Ellen [Mark], you hung out and waited your turn. And it’s really wonderful. And it was actually very rewarding and satisfying for me at the 20th anniversary and the 25th anniversary to be able to function in that capacity with students. Having been a student, it was very, very moving for me.

So I showed my work to Jay Maisel, because there was a little pause and I kind of horned in there, and he looked at it and asked me a few questions and said, “Come with me.” And he walked me over to Greg Heisler, who to this day, I really, really admire and respect all that he’s brought to our industry.

And Jay said, “Look at this stuff.” So Greg looked at it and he looked at me and he said, “Okay, what are you doing right now?” And I said, “Well, I’m a staff photographer at a 35,000-circulation daily, blah, blah, blah.” He goes, “Okay, here’s what you do: Quit your job and move to New York.” Literally those words. That quickly. And I said, “Okay, that sounds good. I’ll do that.”

And later on, after becoming very good friends with Greg—he actually had an apartment in Little Italy that he had just moved out of, but he still held the lease on it. He gave me the apartment, so that I had a place when I landed. I had two bags and one camera bag. He said, “I could have said that to a hundred people, and one of you would have done it.” So he always really admired that fact. So I literally went back—this will give you an idea of the climate at the newspaper as well.

We won a lot of regional awards. We had one guy that won the POY, Joe Luper, and we were incredibly supportive. And we were competitive, in a very healthy way. We went out and every time we tried to come back with something really good, no matter what. It was a really great photo paper. And when I went back and I told the story, everyone was like, “Yeah! You gotta go. You gotta do it. You gotta do it!” So it was always accepted. And it was quick: “I’m giving my two weeks notice. I’m moving to New York. I’ve got this apartment all worked out.”

“I really believe that if we shine our light on something, the universe reflects back. And all I did 24/7 when I was at the paper was photography.”

And the one thing I did leave out momentarily here, is that Greg Heisler said to me, Chris Callis, who was an incredible photographer—is an incredible photographer—he did some amazing work around the time that we’re talking about as well, mid-to-late ’80s, that was kind of his time—Greg said, “Chris Callis is looking for an assistant and I think you should go interview with them. I’ll call him for you.”

So he called him and I went over to Chris’s, and Chris was really interested in manufacturing his own lighting equipment, and he had a mill, and he had a whole metal shop and a wood shop.

I have skills in all those departments and when I talked to him, he started asking me about that. And I said, “Yeah, absolutely. I can work the mill. I can run the mill and I’ve been around other equipment, that’s not a problem for me.” And he said, “Listen, this is really unfortunate, this timing, but I just hired a first assistant two days ago. I let Greg know that I needed someone, but that’s sort of passed. I hired Irving Penn’s first assistant.” And I said, “Well, okay. I still plan on moving to New York.” I wasn’t deterred by that, but it would have been nice to have a locked-in source of income when I got there. But I was confident that I could figure it out.

So, I went back to California and I had a message on my answering machine from Chris. And he said, “Listen I don’t think it’s going to work out with this other guy. If you’re willing to move here, I will hire you. Full-time.”

And so I moved to New York and I had a position right away. I got there on Saturday and on Monday I started. The guy he had hired, he just really didn’t have any of those practical building skills that I had. And Chris really wanted that. And it was all very amicable. So it wasn’t ever a thing.

It was nice to be able to move to New York and have a job that I went to. I got paid $80 a day, taxes were taken out, and I was happy as long as I could by film and paper.

I set up a little darkroom and everywhere I lived in New York: I lived on Mulberry Street in the Village, then I lived in Prospect Park in Park Slope, then I lived in Tribeca, and then I finally landed in the West Village on Leroy Street. That’s where I built my first studio that I actually had enough room to shoot in. And my darkroom.

Angelina Jolie for National Geographic

George Gendron: Dan, a minute ago, you said when it looked as if the assistant job was falling through, you said, “Well, my response was, ‘That’s okay. I’ll figure it out.’” Not a lot of people would’ve reacted that way. When you think about New York as the mecca, everybody—writers, editors, photographers, designers—felt they had to go there, for the excitement and to prove themselves. But for most people it was a really intimidating prospect. Getting there, getting work, breaking in, all of that stuff. What gave you that confidence so early in your career—that “Well, I’ll figure it out”?

Dan Winters: Really, honestly, I really believe this: If we shine our light on something, the universe reflects back. And all I did, 24/7 when I was at the paper, was photography. I would stay many, many, many hours after I was off, working in the darkroom. I shot constantly for myself. I really believed in myself and I studied photography extensively. I fancy myself as being a scholar on photography. I continue to this day to do research, and I’ve written quite a bit about the history of photography. So it kind of wasn’t an option. I talk to students often and I tell them, “If there’s another path that you could consider going down, besides photography, I would suggest you take that other path regardless of what it is, because this is not a casual pursuit at all. This is 100 percent commitment.”

I was completely committed, and I also feel like there was a level of confidence because I made that inroad with Greg, and I felt like he could probably steer me somewhere. Worst-case scenarios, I could start shooting for the Village Voice, which wasn’t actually even a worst-case scenario, but one scenario was that I could shoot for the Voice or for Time Out or Metropolis—pick up some freelance work.

Another thing I’ve spoken about in the past is that, at that time, the worst thing that could happen is I would land on my parents’ couch. The parachute was going to open no matter what. If I couldn’t make it, if I couldn’t, I knew I could at least regroup on my parents’ couch. And that was a really comforting feeling, to know that the parachute was going to open regardless of what happened. But I do feel like I have a lot of self-confidence, and I think it’s not arrogance at all. I think it’s based in a belief that I’m being very thorough with my pursuits and being very realistic, I’m not lying to myself about the effort I’m putting into it. I think when we start doing that, we go down kind of a rocky road, if we’re dishonest with ourselves about how much we’re putting into it.

I’ve had relationships, I had a girlfriend for a while who was working as a photographer as well. Some conflict that arose in that relationship, through my feeling like she wasn’t putting as much as she needed to into it, in order to get the kind of return that she needed. But she’s doing fine now. She’s a cinematographer and everything’s fine. But I remember really feeling like I had to do this 24/7 in order to make it work.

Musician Robert Cray for Rolling Stone

George Gendron: So you’ve landed in Manhattan. It’s 1988. I’m curious what magazines at that time really resonated for you personally, as a reader, as a photographer, visually, for whatever reason. What were the magazines that you were really drawn to?

Dan Winters: I worked for Chris for a year and in that time I shot nonstop. I shot every weekend. I did a bunch of photo projects. He would go to his house in Mattituck every weekend with his wife, Lisa Jenks. So I had his darkroom, which was a huge—I had my own darkroom at home, but he had this really big, beautiful, darkroom that I worked in and printed constantly.

I had a box made that was embossed and it was loose prints and it was all very calculated. When I got the job from him, he said, “I need a one-year commitment.”

And I said, “That’s not a problem. I’ll give you a one-year commitment.”

And, as my departure time approached, I would remind him, “Okay, I’m going to be here two more months.”

And he’s like, “Ah, you’re not going to go anywhere.”

I’m like, “No, I’m going to be here two more months.”

So I replaced myself with a guy named Dave Bashaw, and I left right at the same time I showed up, which was November of ’88, and November of ’89, I was gone. And I had already printed a portfolio, had a whole plan of attack. I had a list of magazines I wanted to go to. And the first one I went to was Horace Havemeyer III’s Metropolis, which was doing some really cool stuff and was really beautiful. Jeff Christiansen and Helene Silverman (Gary Panter’s wife) were designing it. And I thought the design was really really smart. It kind of had Bauhaus Swiss overtones to it, which I really loved. They used photos big. It was a large-format magazine. I lived in Tribeca at that time and I walked over to their studio. It’s called Hello Studio, which I always loved, because they’d answer the phone and say, “Hello Studio.”

I dropped off my portfolio and I went to get something to eat. And I went back to the house and my light was flashing on my machine and I got two assignments in—it took an hour to get two assignments! And I thought, This is going to be so easy! Wow, crazy! Right off the bat, right off the bat, getting work.

Patrick Mitchell: They really need me.

Dan Winters: They really need me. Everybody needs me. So I did those. And honestly, what I was looking at were magazines not for the subject matter of the magazine as much as the way the subject matter was being handled, and American Health—they were doing a great job there. Beautiful design, using photography beautifully. At that time, I believe EGG magazine had just launched—they were real allies of mine. Jim Franco was the photo editor there and he gave me some great assignments. My first travel assignments. I think American Health was the first travel assignment. I flew to Chicago and shot a portrait and flew back in same day. I just remember how liberating and free it felt to be able to be earning a living in the way I was. And it was different than the newspaper, because the newspaper had, of course, job security. And this didn’t, but I felt like if I did the best I could every single time I shot, that was how you create job security. And I still hold that to be the case.

Rolling Stone obviously was, in my opinion, incredible. Harper’s Bazaar was amazing. Interview was doing great work—Tibor Kalman was art directing it at that time, and he’d never done a magazine before. But I felt like he was doing such incredible work. Actually, Tibor became a real champion of mine. I showed him my work, and he sent me to Brazil and he sent me to Venezuela, and he was giving me work in New York, and all these things kind of started to build. And obviously I started to get higher profile subjects for my portrait, so that compounds itself.

And I had a funny story about Rolling Stone. I looked at the masthead and Fred Woodward was creative director and I thought, Well, creative director is the guy I want to talk to. I know there's a photo editor, but the creative director is the guy I really want to talk to. So I started calling his office. Geraldine Hessler was his assistant at the time, and every time I called, she said he couldn’t come to the phone. I called so many times that I sort of had established this phone relationship with her.

And I was like, “Hey, Geraldine, it’s Dan. Hey, is it possible for me to get on the phone with Fred?”

And she’s like, “Oh, he’s in a meeting right now.”

And I said, “Geraldine, just tell me straight, is he really in a meeting right now?”

And she said, “No, he’s not really in a meeting right now, but he doesn’t really take phone calls, like photographer phone calls.”

And so she said, “I’ll tell you what. Bring your portfolio up here to my attention and I’ll look at it. And I promise you I’ll put it in front of Fred.”

And she did. And I got a call that afternoon, late, from Fred directly. And he said, “Can you come up tomorrow and meet with us?” And I said, “Yep.” So I went up—rode my bike up there. I rode my bike everywhere in New York. I rode my bike up there and went and had a meeting. And it was [Fred], and Jodi Peckman, and Nancy Jo Iacoi, and Laurie Kratochvil, and Geraldine. And we sat in a room and went through the portfolio and I walked away with a couple assignments and shot for them pretty regularly from then on out.

“I felt like if I did the best I could every single time I shot, that was how you create job security. And I still hold that to be the case.”

George Gendron: So they really did need you?

Dan Winters: They did need me. At the time too, and I’m not really sure how much it factored in, because [Mark] Seliger was doing pretty big shoots for them at the time that had a lot of production and stuff. I was still sort of working by myself. I had a rollercase that had my lights in it, I was using Normans, so I had a few 200-B, 400-B Normans, and I shot with a Hasselblad, always. So that was my shoulder bag. I was working really light and I was traveling alone. And I could spend a considerable amount of time on a project and it would be pretty low-impact for them financially.

I was very frugal. And so I think there’s probably an element of the fact that I could really work economically for them. But also I felt like I was making good work for them. I started working for GQ quite a bit. Karen Frank and Robert Priest. In fact, it was the first time I ever got a raise.

I remember that everybody’s day rate at that time was $350. And that was everybody, from The New York Times Magazine to Fortune. It didn’t matter. It was $350. And I think the assumption was that everybody worked for $350. And I found out that actually wasn’t the case. But they kind of present as though that’s the case. Like, “No, that’s our day rate.” And I realized later that the day rates are actually fluid. I remember I was in the elevator with Karen and Robert, and Robert said, “How much do we pay you a day?” And I said, “You pay me $350 a day.” And he said, “Well, we’re going to pay you $650 a day now.” And I thought, Wow, I just got a raise. That’s pretty cool.

George Gendron: Wow. Nice negotiating! [Laughs].

Dan Winters: Yeah. Right? I know. Totally. I could’ve asked for more! But those were amazing days. And it’s interesting you’re bringing up that time. I suppose you’re bringing up that time in photography and magazine publishing because that’s kind of my time, but that was a really magical, really magical time for me.

I know magazine photography very well all the way from, let’s say pre-war Life all through the war and then into LOOK and Nat Geo and a lot of the picture magazines that existed. And then, in through the sixties and seventies, and certainly the way the photo essay developed and everything from Walker Evans’ work with Fortune pre-war and then post-war, like Eugene Smith .

I do feel like there was this notion that there was a school of photography for each magazine. So, the “Fortune school of photography” or the “Nat Geo school of photography.” And there was a level of expectation, I suppose, on the reader’s part to get this sort of a similar aesthetic delivered to them.

I do know while Nat Geo’s aesthetic and the way those images were presented slowly changed over the years, and I think that Alex Webb was largely responsible for the shift that took place in Nat Geo’s stuff. Tom O’Brien. Was that his name? He was the photo editor there for a while, who hired Mary Ellen Mark to do a black and white photo essay and hired Greg [Heisler] to do these beautiful, lit portraits and Michael O’Brien to do these beautifully lit portraits that really deviated from Nat Geo’s standard aesthetic.

So there was definitely this push for individuality and for work that was, singular and identifiable, and it was really fostered by the magazines I think. And I feel to a degree there was an expectation at some point that I was going to be delivering work that was maybe unique to me and feeling like, “I’m kind of a baby in this world. I’m trying to develop a sensibility.” Even back then I was really aware that style was very fleeting, and having a sensibility or an opinion about the world—the way things function, an opinion about photography and what makes good photography—was much stronger than a stylistic approach, which was very thinly veiled, I think.

Millie Bobby Brown for Entertainment Weekly

George Gendron: It’s interesting you talking about this because of course, although the time frames are slightly different, on the writing side you had the New Journalism.

Dan Winters: Yep.

George Gendron: Which, from the editorial perspective, did exactly what you were describing, which is suddenly, you could identify one author from another simply by their style and their approach.

Dan Winters: Sure.

George Gendron: People were willing to take risks. And Tom Wolf develops writing block, and his editor says, I don’t know, “Write me a letter.” And they publish the damn letter, just, take out “Dear Byron!” And there was this sense of wild experimentation that was really thrilling.

Dan Winters: Yeah, I don’t know if you remember Tom Junod, the piece he wrote on Fred Rogers for Esquire?

George Gendron: Yeah, sure.

Dan Winters: He basically wrote a piece on himself and how the Fred Rogers encounter affected him. It started out as a profile on Fred Rogers. I shot that one, actually, and that was one that really resonated with me. And the stuff Mike Sager was writing. And yeah, there’s a lot of, you know, Robert Draper who was at Texas Monthly at the time, but then, New York stuff as well. But there were photographers that were doing work that were—it was so inspirational.

When I see magazines now, there are exceptions and there are exceptional pieces where there always were exceptional pieces, but I feel a lot of the magic has gone away. I feel the “event photo,” or the “event photo essay,” or the “event story” that I experienced so many times in early part of my career, where you just, you couldn’t believe that Matt Mahurin did this photo for Rolling Stone. And it was so beautiful and so inspirational you were really challenged and inspired—not to trump what he did, by any means. But to really just push your own work.

And this was something that was very common in my experience: Albert Watson doing a photo essay on this or that, or Seliger doing a photo essay on this or that, or a beautiful portrait, or seeing a photo essay by Mary Ellen or… You were really challenged, but also just inspired, and also just kind of almost taken aback. The “event experience” is probably the best way I could explain or describe what I mean. And I remember so many of them. I remember opening Rolling Stone, for example, and seeing something and just being so blown away that I felt like, Man, this guy just upped the game!

George Gendron: And people would talk about…

Dan Winters: And people would talk about it. Yeah.

George Gendron: …the story or a photograph for weeks.

Dan Winters: Absolutely. A hundred percent. Yeah. People would tear them out of the magazine and tape them up to their walls. And yeah I went to a party one time, and one of my photos was taped to the wall of a party of someone I didn’t know. I said, “Whose house is this?” Or “Whose apartment?” and “I want to, I want to tell them that I shot that photograph.” And they’re like, “Oh man, that’s so cool. It’s such a beautiful photo.”

But really the expectation became really high. Everyone felt like they were a part of something. It was a thing—I don’t want to say it was a movement, but there was this. Karen Kuehn and was shooting. And Chip Simons was shooting stuff. And it was experimentation, and it was social awareness, and it was like reverence, and was concept. And it was so much more difficult to research people back then.

I research people now, it takes me 20 minutes and I know someone’s life story, at least a part of it. And I’ll watch a couple of interviews and I’m like, “Okay, I got it.”

When I go on a job, I have a really good idea of what their dog’s named, for Christ’s sake. You can get every bit of information. I remember getting assigned to shoot Ryuichi Sakamoto. And I’d never heard of him, and I’d never heard any of his music. And I had to go to…

Patrick Mitchell: … Tower Records [laughs]?

Dan Winters: I didn’t go to Tower for this [laughs]. I went to The Underground. It was just off Bleecker, and there was a bar. It was a below-street-level record store that I used to go to all the time, and I found something. But yeah, Tower—I’d go right over there on my bike. I usually walked over to The Underground and bought stuff. But, that’s how you did it. I mean, I tell my son about writing papers in college and how difficult it was to spend eight hours at the library, and you can do it now so quickly with the information that’s at your fingertips.

George Gendron: Dan, what happened to that sense of experimentation? Why does it seem that there’s so little of it now?

Dan Winters: Well, if we’re talking about now, like the time we’re in right now, money is a big factor. And the budgets are very low, and they’re usually flat-rate budgets. So they’re “all in.” And they’re incredibly low. They’re able to attract people that will work for nothing. And that’s kind of what they’re getting, oftentimes. They’re getting that.

Patrick Mitchell: The value isn’t there for…

Dan Winters: … The value’s not there. And people don’t value it. And it’s like, “Oh, it’s just a picture of a guy. This guy has a good Instagram, so we’re going to hire him and send him. And we’re going to pay him a thousand dollars, all-in.” Which, when I used to shoot for Metropolis, I’d shoot a whole job and say the budget was $250 all-in.

And so what I would do is I’d say, “I need to make this much.” So I’d say, “Okay, four rolls of Triax is what I’m going to give to this job. I’ll process it and print it myself, and I’ll make $200, or whatever.” It would be $250 or whatever. And it still holds true: you can shoot it, you can process it yourself. You can transmit it yourself, and you can work pretty cheaply. And sometimes I do that. Pretty rarely, though, because there’s money in the advertising sector. And there’s money in tech.

“When I see magazines now, there are exceptions and there are exceptional pieces where there always were exceptional pieces, but I feel a lot of the magic has gone away.”

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah, I think it’s safe to say that when big publishers look back at whatever they did wrong to get themselves in the position they’re in now, it wasn’t spending too much money on photography.

Dan Winters: I would agree with you [laughs]. What was the great quote by Greg Heisler where he said—I saw him speak one time and he said, he said, “Yeah, magazine photography. You can literally make hundreds and hundreds of dollars.” [Laughs]. I thought it was hilarious. I still use that when I speak, of course I always credit him, but it is true though. It was never really like a money-making thing for me.

I felt like I was a part of a community and I felt grateful that I was a part of that community. I knew all those guys. We had parties. And Matt [Mahurin] would have a party or Bill Duke, every year he had a Halloween party, and everybody went to that.

And one year Mark, and Matt, and Frank Ockenfels, and Brian Smale, and this great list of people, including some illustrators, we all went down to Mexico. And we hung out for a week. And every night we showed work and laid in the sun and drank beer. It was just this great community, and I felt like I was a part of that community, and that community was—Fred Woodward was there—we kind of watched out for one another to a degree. It was a kind of beautiful moment, and it was a moment. I don’t think that exists anymore. I think there’s a lot of people that are shooting for magazines that really don’t have any business being in the pool. And I think a lot of it has to do with budgets.

Patrick Mitchell: You already explained how you got to New York, and you didn’t really have to make a choice, but was there a point back in Thousand Oaks where the idea that New York was in your future, that popped into your head?

Dan Winters: Actually, I felt like LA would be my “New York experience.” I didn’t think I’d go to New York. I’m certainly grateful that I did. And I do know designers—DJ Stout, we’re talking about Texas Monthly—DJ Stout to this day when I speak with him, New York comes up. Because he never went and he feels, as successful as he’s been, he feels a little bit like, “I didn’t do New York.” And he was hiring all New York photographers at that time. But my sights were on LA work. Entertainment. I really love music, I’ve done a lot of music stuff and I felt like LA would be a good place for that. Obviously any kind of entertainment stuff was in LA or, not all of it, obviously, but there was a good deal that was in LA. So I thought that that would be my move. That I would probably stay in Ventura County and start trying to get work in LA, whether it was LA Style or or even just go to New York, show work, and be an LA guy for the New York magazines, like Interview and those guys. That’s probably what my plan was, but I was pretty fluid with regards to the path I took.

And again, I think that was largely supported by the confidence that I… I told my son, “Do your best to not have an overhead.” And if you don’t have an overhead, you have a lot of freedom. Once you get an overhead, you cease to have that freedom. Mine was very, very low. I was living very economically.

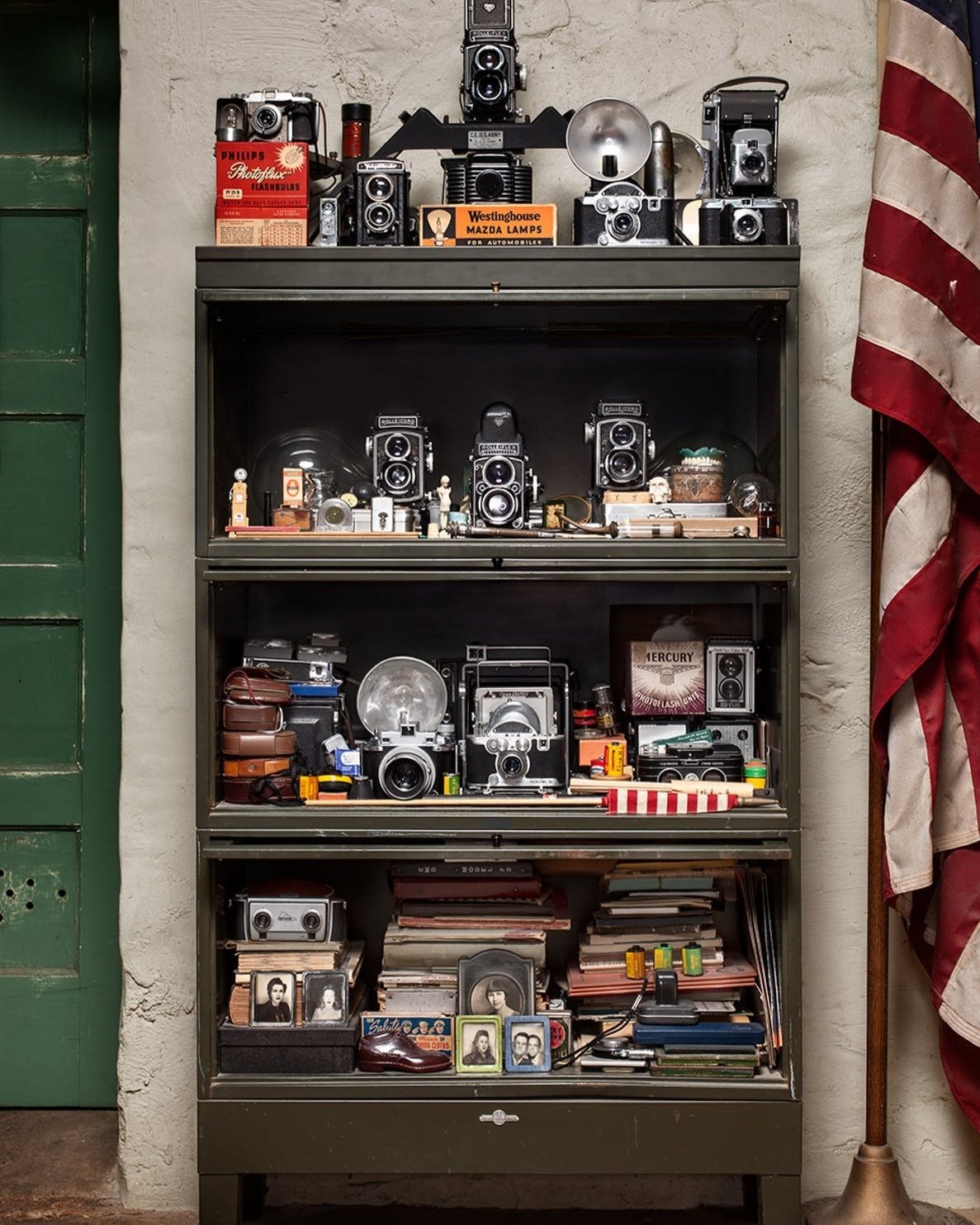

The one thing I remember when I moved back to LA was that I had acquired a whole lot of books. And that was the one thing that when I moved to New York I didn’t have. I had a couple books. And I don’t know if you remember A Photographers Place over in The Village. I mean in Soho. Harvey Zucker —and I bought so many books off of him. It’s not even funny.

That was kind of continuing to be sort of a major part of my passion: photo books. But I think LA would have been the move probably that I would’ve made. I’m not sure—at one point I may have moved to New York, but, I think, when someone like Greg says that to you, you take that as sage advice. And I could have completely missed that opportunity and not done it, and I don’t know where things would have gone. I certainly know I would have still been doing photography. Never an option. And it was really not an option to not be doing magazine photography, but it would have gone down differently.

Leonardo DiCaprio for Wired

Patrick Mitchell: In an interview you talked about some great advice Jay Maisel once gave you. He said, “If you want to become a better photographer, become a more interesting person.” Based on your career, this has been true for you. And I have a theory that being interested in a lot of things from a young age somehow gives you a sense of security for, if/when your first career choice maybe doesn’t go as planned. Do you think that mindset has helped you survive?

Dan Winters: Yeah. I had that mindset long before I heard that from Jay, but I wasn’t really aware of it. We were a very working class family. My dad was a welder. And the one thing my parents did is they fostered my interests. And regardless of what it was, whether it was beekeeping, or woodworking, or model building, or photography, or filmmaking. My mom worked at a bank as a teller and down the street from the bank in the little town I grew up in Moorpark, California, was the library, and I would walk from school to the library at 3:30 or whatever it would be—and I would stay at the library for a couple hours until she got off work. She’d pick me up and take me home.

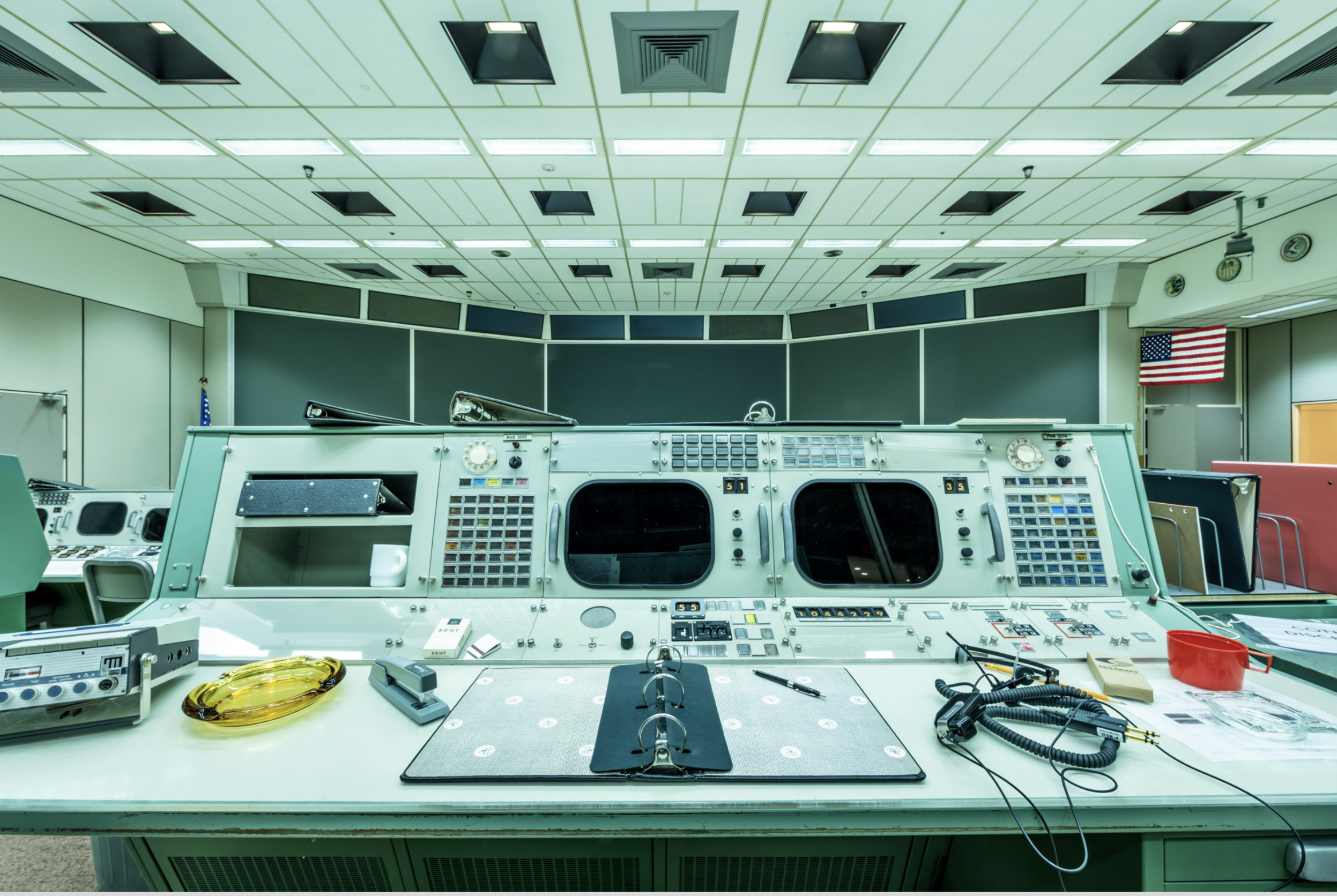

So I had this constant exposure to information that I really grew to value—any of those sort of specific pursuits with regards to that. So world history, European history, Civil War—whatever it was—aeronautics, military history, a lot of science stuff. So yeah, I do feel like I’ve always really been hungry for knowledge. And the knowledge that I possess, and have possessed, and continue to seek out, has certainly been an ally for me with photography. I’ve done a lot of aerospace stuff and I’m very knowledgeable about aerospace, and the history of aerospace, and how things work. And I’ve done multiple—I’m working on a four-year National Geographic project right now on the Artemis program. I get these jobs because the editors know that I know about the subject. And if you know about the subject, you can interpret it in a way that someone that doesn’t really understand that well. And that’s not a criticism, because I know there are photo editors that really liked the idea of, “I got so-and-so to shoot this, it’s totally not what he shoots, so let’s see what his take on it is.”

But something as complex as a learner program over four years, you kind of want someone that knows, like maybe someone would see something and react to it. That’s not really that significant a piece.

For example, there’s also prisons. Over the years I’ve gone to prisons many, many times. And there was an early Texas Monthly assignment where I went and shot at prisons in Texas and did a photo essay on that. That won some awards, and I think it planted the seed. And people said, “Dan knows how to navigate prisons.” And so I’ve done a lot of prison assignments. Or, even with celebrity portraiture, where you know how to navigate that world, and you’re knowledgeable about that world.

I’ve really made a point to try to understand human interaction, how that works. Like, What’s the best way to get from the point where the subject shows up to the point where you’re photographing? What kind of pleasantries…? And sincerity, I think, is the best tool you have. If you’re insincere, I feel like people can sense that. There’s also that reverence for your subject matter. But yeah, that quote from Jay is absolutely true: knowledge outside of photography is as important as knowledge inside of photography.

George Gendron: Picking up on that question from Pat—from an early age, there are two really striking characteristics that you seem to possess. One is this insatiable curiosity, and the other is this passion, maybe even obsession, but a passion for making things. Where did that come from?

Dan Winters: The curiosity, I think, is you just make a choice: either you’re going to be engaged or not going to be engaged. And we’re this biological organism navigating a physical space. And the thing we all have in common is we’re in the same space, right? So how much do I want to know about the space and what it offers and what exists within the space? I think that curiosity piece for me is like trying to make some sense of, yeah, I read this great quote the other day. I can’t remember who it was from. I wrote it down, but it said, “Think of yourself as a soul with a body rather than a body with a soul.” And I thought that was kind of an interesting way to sort of bracket that. And the idea that, first and foremost, you’re this soul having this physical experience.

But the making piece, that started at a very, very, very young age. I think my dad and I built our first model, it was a World War I, British SE5a [biplane] fighter. And we built it together. And painted it together. It was a magical experience for a number of reasons. One is because it was one of many things that my father and I did together. And I learned an immense amount from him. But secondly, the satisfaction of starting in one place and a definite ending, like “we’ve completed this task.” But I got really into woodworking and making my own airplane models, not kits. I learned about painting and airbrushing and I learned about—we built a lot of kits—so I started scratch-building models out of plastic as well. Started scratch-building spacecraft and this and that.

And that was really inspired by 2001. And I had an 8mm camera, and I would film my models against black, like they were going through space, and do stop-motion animation things. And you’re really into creating these worlds. And, as photographers, we’re completely reliant on something to sit in front of our camera, right? We can’t just conjure like a painter. We can, I mean, if we make the thing, and so I really got into and started to try and understand the way special effects worked, and the way miniatures worked into special effects.

And I started working on a pretty high level by myself doing miniatures. And then I approached ILM, Industrial Light and Magic, who did the miniature effects and special effects for Star Wars. I started taking pictures of my models and sending them to them and eventually was invited down to take a tour. And then eventually started working in the special effects industry, when I was still in high school, as a model builder. That was incredible.

I had Work Experience class, so I’d take two periods in my senior year, and then the last four periods were work experience. It was a pass/fail. So your employer basically either you passed or failed kind of thing, and you got school credit, provided all your other mandatory credits were taken care of, which they were. So I would go to my first two periods and then I would drive down to Hollywood and work in a model shop and drive home after work. And I did that for quite a long time.

So all of those building things, I mean, that’s kind of the thing that Chris was talking about when he was interested in hiring me—the idea of “how much building skill do you have?” And I had a lot of building skill. I’m good at building.

And I have a huge shop here at the studio: full-on chop saw, table saw, presses, everything. And we do a ton of building now: set building, all kinds of things. I think it’s just a progression. And once again, it’s also a desire to understand how to do something, as a kid watching Conquest of Space or watching 2001 or watching Thunderbirds, Space 1999. And all those British shows that used a ton of miniatures, like UFO, and trying to understand how that was all done and starting to experiment without any guidance.

I didn’t know anybody that was in the special effects industry. I didn’t know any model builders. I just kind of was making it up and trying to figure out how to do it. I think that attributed, obviously, to the stuff we do today with regards to—I just finished a film, a 35-minute film—since the science fiction films have been doing really, really well with the festivals, and it’s got a bunch of miniatures in it that I built.

I just think the building thing was just a byproduct of the curiosity: Start with the question, and then everything else kind of falls into place as you try to solve the problem.

George Gendron: And these different activities feed each other. I was struck by the story you tell in your book where you’re doing a portrait of Helen Mirren and she walks in and she’s absolutely blown away by the set, which you happen to have designed and built yourself, single-handedly.

Dan Winters: Yeah. One thing I think is, when we go the extra mile like that and really have something, there’s an expectation, even though it’s unspoken, like, “Okay, we’ve done all this for you, we need you to sign on for this.” And of course, there were no requests on her part. She walked in and she was like, “Oh my God, is this for me?”—I remember very clearly—“I’ll try to do it justice!” And then she certainly did. It was wonderful.

Helen Mirren for The New York Times Magazine

George Gendron: Yeah, that was an amazing shoot. God.

Dan Winters: We scanned that negative just a while back and I was blown away as to how little film I shot on that job. I think I shot, like, 35-40 sheets of 4x5. It was a very little, considering the effort, but it worked. It just worked right away. And there’s a tight portrait of her and there’s that pulled-back shot of her in the room. And I didn’t really work it that much. It just seemed like, “Okay, we’ve got it, it’s done.”

And I think that’s an interesting challenge as a photographer too: to understand that shoots have arcs. And when you start, sometimes, it happens very quickly. And sometimes it takes a little work. But our job is to be conscious about when it’s working and to understand, and I say this out loud on shoots often, because it’s important—and I think everybody understands that, “Okay. It’s working right now. Okay. We’re getting it right now. It’s working right now. And is there anything that we can do to make it better?” To me, when I say a “perfect photograph,” I feel like what I mean by that is it’s a photograph that can’t be improved upon. There’s nothing I can think of that would make this photograph better. And that’s a really satisfying way to look at an image.

I see Stieglitz’s “Winter, Fifth Avenue,” and I don’t know what you would do to that image to make it better. It’s perfect. And those are rare. Those images are rare. If you can make one of those in your career, I think you’ve—and that something that contributes to the form of photography—I think you’ve done a great job. You’ve done a great service to your pursuit, because they’re elusive. Very elusive.

Patrick Mitchell: You mentioned the Greg Heisler quote earlier about making “hundreds and hundreds of dollars” as a photographer. Pretty funny, but terrifyingly true. In my case, because my current clients are not deep-pocketed, I’m still pretty much paying the same rates we paid 20 years ago. Photographers and illustrators talk a lot about this. In your experience though, have commissions kept up with inflation?

Dan Winters: As far as rates go, I do a lot of illustration as well, and I think illustrator rates are really low. DJ at Texas Monthly used to talk about “the end of the year” would be “pretty lean.” And so the magazine tended to have a lot more illustration than photography, because it was cheaper for him to commission illustrators than it was photographers.

I do love illustration. It never bothered me at all. But it is interesting that yeah, rates haven’t changed a lot. I remember, actually funny you should bring up the Helen Mirren image, because when I was shooting that image, Kathy Ryan from The New York Times came to the shoot. It was in LA, and I had spent the night in the studio because we’d worked so late. I didn’t want to drive all the way across town and then drive all the way back for an early call. So I slept on the couch at Smashbox [Studios]. Kathy showed up and she said, “Oh my God, Dan. I’m so excited to tell you this. We’re paying $500 a day now. I just got it approved.” That was 2006—it had been $350 up to that point for The Times.

I think the magazine clients, yeah. Kept up with inflation? I’m not really sure. I’d have to do the math, but I’ve gotten raises all along. I don’t charge now what I charged 10 years ago. I get more. Sometimes clients allow me to bill multiple days because it’s easier for them to get that through. So it’s just like, “Well, bill me for three days because I can get that through the beancounters really easily.”

Patrick Mitchell: Well, the justification for photographers used to be, “Well, I’ll make up for this with my commercial work.” But it seems like all of that is disappearing.

Dan Winters: Yeah. I think I’ve been really fortunate. You know, I do a lot of entertainment stuff for Netflix and Apple and those are pretty great with regards to what they pay. I do research projects for different tech companies, where I’m shooting long-form projects for them. I get good money for those. So it’s a blend. I also feel like, to a degree, with magazines—and I’m grateful for this and I don’t insist on it—but it certainly has come my way, they’ll pool their money a little bit and say, “Okay, we’ve set aside this much money for you to do this project.” And it’s a good rate and it’s a good project for them.

They want it done and they want me to do it. So I’m grateful for that. Other things come in that I have to make a decision one way or another. If you don’t want to do it—I have a set rule with regards to travel jobs where, “Is this going to be something that is worth my while outside of the experience of doing it for the magazine? Am I going to use this picture for anything? Is it worth me leaving home and leaving my family for a week for something that’s not really going to be important to my archive?” Monetarily, it’ll be something that I’ll do.

Patrick Mitchell: On shoot day, what’s your process—physical, emotional, practical, spiritual—for getting yourself into the moment?

Dan Winters: Depends on what it is. If it’s something that’s a really simple thing, where we’re in a studio say, in LA, and it’s seamless or it’s background, not a lot of production has gone into it, that’s kind of a more intimate thing. Those are great because they’re—my wife and I have this joke: The one thing I know how to do is I know how to take pictures. That’s the joke, because everything in my life can be a shambles, but I know how, when I’m put against the wall, I know how to make a picture. And I know how to solve a problem. And, hopefully, you hit a double or a triple. You know, if you hit a home run, that’s great.

Those are really, really rare as well. Very relaxed. I’m very relaxed when I’m in that element. And I’ve heard people talk about how they get sick to their stomach before something or whatever. And I always feel like if I’m prepared—and I always prepare—I think when we did that shoot with Obama, they told us we could have five minutes. I had six setups, and we had taped arrows on the floor for him to go to the next setup. And there was a camera at every setup, and all the lights at every set setup. And I did 10 minutes. It took—and he stayed for—10 minutes. And we had prepped for six hours. We showed up at the White House at like 6 am, and we loaded in. And I had five assistants. And it was super-buttoned-up, and it was super-planned, and everything was diagrammed.

So everybody knew what we were doing. Every setup was discussed, what it was going to be, storyboarded. And so it just becomes, not a formality completely, but you’re so prepared for this eventuality, that it just goes smoothly. As a result, I really enjoyed that process of photographing the president for 10 minutes. I really enjoyed it. I didn’t feel stressed at all. I felt like I had someone right behind me calling time for me saying like, “Okay, you’re at 45 seconds. You’re at a minute.” It was wonderful.

But I think prep is everything. If you’re ready and prepared—and those are jobs that are portrait jobs that are set up. If you’re doing stuff that’s journalistic, or like this project I’m working on for Nat Geo that’s kind of an unknown, where are you going to go? You have to trust your instincts and trust your knowledge and trust that you have a sensibility and you understand how to apply it to a certain subject.

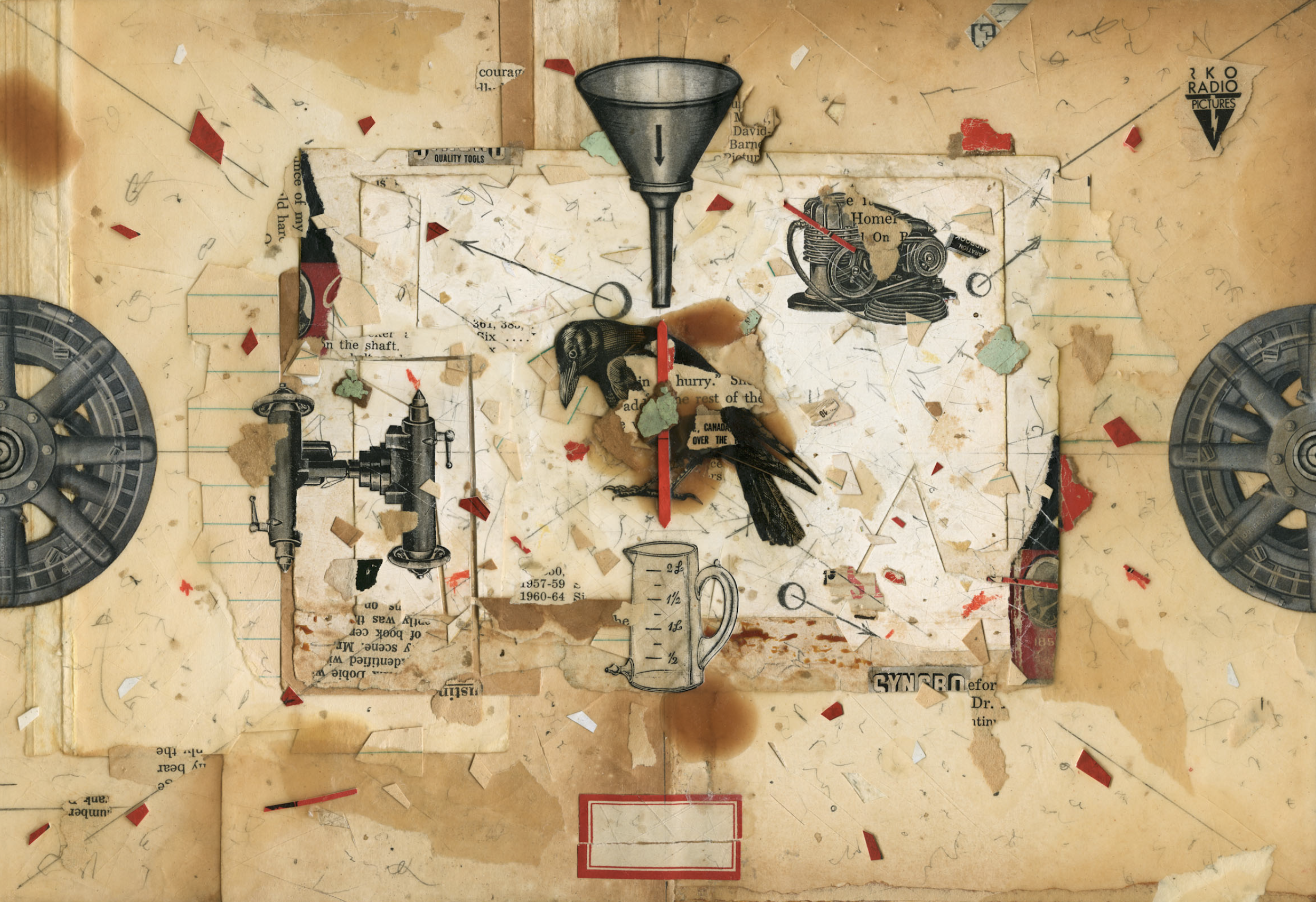

“How much building skill do [I] have? I have a lot of building skill. I’m good at building.” Here, one of Winters’ detailed photo illustration constructions.

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. Well, along those lines, your choice of backdrop is one of the signature elements of your work when you’re not in your studio. When you’re out on location, is that a priority—to find something where you can just avoid hanging a seamless? Because it seems so integral to the work that you do.

Dan Winters: Yeah. When I do those, the kind of painted background stuff, I have a bunch of them that I’ve made. And I have had a couple made for me by a couple in Belgrade. And they sent a couple to me just for free just to try. And the smaller ones are easy to travel with. So I can have them with me if I’m going to do that type of picture. Or I can find something that’ll work, depending on where we’re at. Find something that works or find a location that works or find something that I feel like would be suitable.

I’ve gone to different cities and gone to Home Depot and bought plywood, and bought paint, and painted backgrounds, and taken them to the shoot. I’ve painted tabletops, the day before the shoot, and taken them. Buy paint, paint-rollers, background, canvas, painting canvases, paint them, you know, on location. I’ll find a parking lot usually, or something to work in, roll them out and then take them to the shoot and use them.

So there are a lot of ways. I have these really cool—I was doing this portrait of Bill Gates and I wanted a really beat up, rich wood tabletop to shoot him on. So I called around to prop guys in Seattle and they’re like, “Okay, it’s my day rate, twice. Transportation and rental.” It’s just a fortune. I was like, “It’s totally not worth it, but I want something like that.” So I designed this modular tabletop and it’s all numbered, and it all fits together like a puzzle.

And you can just put it on anything. Any table. So I just went and bought a door at Home Depot, and two sawhorses, and took it to the shoot. And then we put our modular tabletop on the door. And then we returned the door and returned the sawhorses, and got our money back. So, the old stylist trick. And it looked beautiful. I did it for Obama. We made an Obama one. I have an Obama one, I have one that’s labeled Bill Gates. I have other ones I’ve made that are just—they fit into our cases really easy to travel with.

Patrick Mitchell: Do you sketch these setups out before the shoot?

Dan Winters: Yeah. On the Obama one, I just storyboarded it to say, “This is the expectation of this setup. Whether it deviates from that—that’s neither here nor there, right?” But at least I know when I do launches, like shuttle launches or rocket launches, I storyboard those all out. Say, “This is a 50 mil [millimeter lens], there’s a 100 mil, or 35. This is 28mm, and this is the picture I’ll get.” I draw a picture of what I think the image is going to be. That way I’m not repeating myself. I’m not really overlapping cameras at all. So I do feel like all that prep really factors into it for sure. And the Obama one, yes, we definitely, I said, “Okay, this is, like, tight head. This is a picture of his hands. This is him against the window, looking out the window from behind.” All these different ones were all boarded.

Patrick Mitchell: Have you ever asked NASA to bring a rocket back down and do it over again [laughs]?

Dan Winters: Yeah [laughs]. There’s a great Hasselblad ad from the ’60s—maybe the early ’70s—it was a picture of [Buzz] Aldrin on the moon that [Neil] Armstrong shot, where you see Armstrong in the visor. It was in a photo magazine. I’ll never forget it. It said, “Hasselblad cameras cost more, but when you consider the cost of a re-shoot, they’re worth it.” [Laughter].

I felt it was really brilliant piece of copy I thought, because, you know, yeah, normal Joe can’t—I remember distinctly thinking that I would never be able to own a Hasselblad. I remember distinctly thinking, I’ll never be able to afford one of those. I have, like, five of them now.

It’s funny though, when you’re so young, it’s just like, “God, I’ll never be able to afford a Hasselblad.”

I used to shoot with a Kowa 6, which was an awesome Japanese Hasselblad, and it was wonderful.

Winters does a lot of work in aerospace: ”I get these jobs because the editors know that I know about the subject. And if you know about the subject, you can interpret it in a way that someone that doesn’t really understand that well.”

Patrick Mitchell: During the previous administration, I remember seeing a lot of photographers, like Nigel Perry, posting pictures of the previous president. And it made me wonder, have you ever photographed somebody you really didn’t like? And if so, how do you handle that?

Dan Winters: Yeah, I don’t think I would. I would handle it by not doing the job. Just not taking it. It just wouldn’t feel right to me. I don’t really want that picture.

Patrick Mitchell: So that’s a prerequisite.

Dan Winters: Yeah. I don’t really want that picture. And I don’t think I need it for anything. And someone else will do it. So I’ll pass. That’s the way I would have handled that.

And then there’s also photographers like Richard Burbridge, who would have an agenda. And they would go and they’d make the most offensive portrait you can possibly imagine of someone’s face when they look disgusting and sweaty. So there’s that whole thing too.

But I like to really have a human—my wife, it’s funny what happened one time where I got assigned to shoot George Bush, Jr. [“W”], and I didn’t want to do it. So I didn’t do it. And then I didn’t do it again when I got an assignment to do it. And then there was a third time.

This is one of those things where he’s totally a nice guy or whatever, but just couldn’t make peace with the idea that we like attacked a sovereign nation without provocation and killed a lot of civilians. That really never sat right with me. I know Saddam was a dick, but they didn’t attack us.

So anyway, I never wanted to do it. And then I got this third offer to shoot Bush and I said, “Nah, I don’t want to do it.”

And my wife said, “No, you should do it.”

She said, “He’s out of office now. You’ve objectified him all this time. Just go do it. Just have an experience.”

So I was like, “All right, I’ll go.”

And it was a perfectly wonderful day at the ranch with him and we made some beautiful portraits of them. And I was able to sort of see him as a human being—and as a flawed human being. Like we all are.

And so it was a great growing experience for me. I don’t use those pictures for anything really. They’re on the website. So I guess they’re being used. But, yeah, I think two things can happen: You learn about that person and you can come to see them as a human being, as a fellow human being. Or you can have a shitty experience, I suppose.

Patrick Mitchell: So your wife gave you that advice?

Dan Winters: Yeah. She said, “You should do it. You should go do it.“

Patrick Mitchell: I wanted to ask you about Kathryn. I know she plays an integral role in the business. How did you guys meet?

Dan Winters: We met in ’91, I believe. I was on assignment for Vanity Fair to shoot Tom Sizemore and Dylan McDermott. They were in a film called Where Sleeping Dogs Lie. We also shot the director, Charles Finch, Peter Finch’s son. And they were doing post-production on the film, and Kath was the post-production supervisor. And so they were doing ADR (automated dialogue replacement) at a sound recording facility in Hollywood. Tom had flown in from Chicago. Dylan was working on something else. So it was like it all had to happen on this day. And so that was the time that the magazine had negotiated with their respective managers, agents, whatever. And so Kath was my contact.

And she’d never done a photoshoot before or anything. She was post-production supervising on this film, but the shoot had to happen on this one Saturday when everybody was in the same place. So I called her from New York just to set things up, and I started talking to her.

And I don’t know if she would admit this, but I felt like I had expectations, a little bit. We’d established that we’re both single and I was probably 28. And so she said, “Well, hey, listen, I’ll help you scout for a location that’s near where we’re going to be working.”

So we ended up on Mulholland. We found a spot on Mulholland that I thought worked really well. It was kind of a cool.

Patrick Mitchell: Isn’t that where people go, uh, “necking”?

Dan Winters: I don’t think you can anymore, but back in the day you could, for sure. You could just pull over, but now you can’t pull over anywhere. They have no parking signs everywhere. So we find the spot and did the shoot. And basically went out every night that week—went to the Hollywood Bowl one night and we just had this great romance and yeah, Vanity Fair. There you go.

Patrick Mitchell: And flash forward to more recently: How did you two decide to work together to make a family business?

Dan Winters: Well it started then, really. She finished that film, which, like I said, she was supervising the post and it was out the door and she started working for Al Ruddy for a little while, who produced The Godfather and a bunch of others. He’s a very old Hollywood guy.

She started going through my receipts because I hadn’t paid taxes in a couple of years, and I had just boxes and boxes of receipts. And I hadn’t billed jobs for months, and this and that. She’s very organized. So she started kind of laying everything out on the floor and looking at everything, and it just organically happened. She just quit her job and started taking care of things and started putting things together and producing and traveling with me. And that happened very early on. I mean, we’ve been working together 30 years.

Tom Waits for Stern magazine

Patrick Mitchell: I read somewhere that you said, “Stop apologizing for digital.” And I’m not sure if that was aimed at pros or all of us, but you first turned to digital in 2013, and in your own words, you have not looked back. I remember the old days photographers insisted everything had to be done “in-camera.” That was what separated the pros from the amateurs. Now we all have these digital tools and filters. Is it safe to say that the only important thing is how you feel about the end result? No matter how you got there?

Dan Winters: That’s a great question. It’s a great question to ask me as well, because I went through that entire arc. I think the thing about digital… So for me, first and foremost, yeah, it’s image. What’s the image, right? And there is a great satisfaction historically about being able to do an image and execute it in-camera.

Now, from an historical standpoint, you didn’t have a lot of options. So you kind of had to figure out ways to execute in-camera. And you were talking about the late ’80s, and you think about Eric Meola and Pete Turner doing these really complicated—remember [Michel] Tcherevkoff?—doing these really complicated, montage-type images and stuff that were all done in-camera on multiple, multiple exposures, duping, all kinds of things. And those were guys that were getting really high-profile work because they understood how to do that. At a very high level, a technical level.

For what I do, I find it very satisfying to do things in-camera. And first and foremost, that’s kind of my priority. Unless the intent is to have a digital element in it, I try to shoot it just like shooting anything else. But at the end of the day, I think it’s still image-making.

I think what the digital world has given to—there’s a technical barrier that historically people that were amateurs couldn’t cross and that’s what professionals held as sacred. And they knew when they left a shoot that they “had” it. They understood the materials. They understood the equipment to the point where they had a confidence level that they were able to achieve the image.

Nowadays, because we have instant feedback—and we have auto-focus that’s incredible—and we can get our exposure right without any problem. The technical barrier, in my opinion, largely has been broken. So what we have then is we have the ability to create an image. At the end of the day, it’s still image-making, I’ve made images on my iPhone that I think are wonderful. It’s just a tool. The camera’s a tool.

I think when I said that probably it was solely because I have a 100-megapixel Fuji system that I use now. And it’s like walking around with a 4x5. And I never would have imagined that I could have that in my bag. I carry it literally in my shoulder bag. So I have a 4x5 in my shoulder bag that I can shoot with, essentially. And the files are actually even cleaner than four-by-five. I spent 30 years shooting 4x5 or 25 years shooting four-by-five because I wanted that high, high, hyper-resolution that 4x5 would give you. And I look at my 4x5 files now, compared to the Fuji files, and the 4x5 files are really dirty and grainy. And you know, it’s just a different thing.

So it’s an incredible tool. It’s better for the environment. I’m not dumping chemistry down the drain, and labs aren’t processing my stuff. And we have the gift of the digital darkroom. There’s not been a bigger breakthrough, in my opinion, to color photography—since the inception of color photography by the Lumière Brothers at turn of the century—as significant as the digital darkroom. The digital darkroom has enabled us to do things that we used to struggle and struggle to do, and never could achieve them properly. Shooting through tons of ND, pulling stuff, over-exposing things, pulling on all the things that we used to have to do to try to get an effect.

I mean, I remember Greg Heisler spent a fortune having Kodak run this pallet of dupe film. So duplicating film is very low contrast film. And he felt like transparency film was too contrasty. So he had them run a pallet of dupe film as 120. And they spooled it for him when it wasn’t available. It was available in 4x5, which he shot all the time, dupe film 4x5.

“I’ve really made a point to try to understand human interaction, how that works. And sincerity, I think, is the best tool you have. If you’re insincere, I feel like people can sense that.”

And so we’d try to figure out ways to work that would accommodate what our sensibility was. But there was a lot of frustration met by the limitations of the photochemical process. And I think that the digital process is vastly superior to the photochemical process. The print quality that we can make is like—it’s leaps and bounds above a photographic print.

We’ve tested, and tested, and tested. And I’ve seen every sort of variation of what a photo from Ilfochrome to [Fuji] Crystal Archive to C-prints, to all those. And there’s nothing better than a beautiful, beautiful inkjet print. The blacks are so deep and it’s just beautiful.

So when I said I never looked back, I think it was because I was implying that I really didn’t lament the fact that the technology had shifted, that I was just embracing the natural progression of the technology. Now having said all that, I just shot a whole bunch of—I just ran 20 rolls of Hasselblad film right before I went on this last trip. So I still shoot film. I still shoot with my Hassys and my Rollies. And I have a [Hasselblad] Xpan that I like to shoot with.

So it’s not that I have any disdain for that process. I’m grateful I came up through that process. I’m grateful that I’ve spent many thousands of hours in the darkroom working. It’s just that I can achieve a four-hour darkroom session—I can achieve a beautiful final image so much more quickly and so much more environmentally-sound than I could in the darkroom.

I know that there’s a whole hip movement among the young people about, “Yeah, I shoot film, man,” and that kind of thing. And I’m like, “Well, that’s cool. I’m glad, because I’m glad that you’re gonna learn that piece of photography and keep it alive. That makes me happy.”

Patrick Mitchell: I know photographers probably worry about, like you said, people hiring people from Instagram, which I have done, literally, one time and never regretted anything more because I went on that shoot and this person just didn’t know what they were doing. They were all “filters” and all “we’ll fix it in post.” And the things they were ignoring at the shoot were just astonishing to me. So you still don’t have to worry about separating the pros from the amateurs.

George Gendron: There’s one point, and I’m trying to think about when it was, it was an interview that you did—it’s on YouTube—and you were talking about this, and I understand exactly what you’re saying, and respect it. However, when you did talk about working in the darkroom and making a print, you just lit up. I don’t know what it was—and I guess the question is, Is there a different psychic payoff that you feel you get somehow from the darkroom then from digital?

Dan Winters: Yeah. My time in the darkroom is, I guess I could refer to it as “sacred” time. You slow down. And there’s a solitude to it that I really like. A couple of weeks ago, I worked in the darkroom one whole afternoon, working on a project, doing some contact printing, and the magic of walking in and smelling that glacial acetic acid and watching the prints come off. That magic that all of us have experienced who have been in a darkroom. It’s still very salient for me.

The thing that I do with the darkroom most now, honestly, is I do photograms a lot. And I do chemigrams or chemical paintings. I spend a lot of time making many hundreds of those. I continue to do that very regularly. So my darkroom work has kind of gone from figurative to abstract, and being in there and creating those images is still as special as it ever was. In fact, maybe more so, because there’s a level of chance when you’re working with chemigrams and with photograms and there’s a wonderful sort of surprise element. And every time it’s an original object, right? You’re not working on, if you have to put a single negative in the enlarger, then use four or five sheets of paper and feel like you have a…

Patrick Mitchell: … They call those NFTs now.

Dan Winters: Yeah [laughs]. There you go. So if I’m making this conventional print of an image, let’s say five or 10 sheets of paper, maybe I get it perfect or get it as close to where I want it as I can. And then move to the next thing. Doing chemigrams and photograms, it’s a one-off object, obviously, and it’s also just, there’s the level of revelation with it every time. But no, I do. I love working in the darkroom. I have beautiful—I have two darkrooms. Both beautiful darkrooms, and very roomy. Yeah, I really enjoy working in there.

George Gendron: Going back to what you were talking about a moment ago, Dan, which is the so-called “renaissance” of film photography among the younger people. I hate to sound like an old cynic, but I think, for a lot of them, a camera’s a fashion accessory. And they shoot the film and they don’t go into a darkroom. They drop it off at Walgreens.

Dan Winters: Yeah.

George Gendron: And so I, think it’s a slightly different thing.

Dan Winters: They go [laughs]. They shoot the film and then the first thing they do is scan it. Which cracks me up because it’s like, “Well, you just turned it into pixels, and it’s a grid now.” And the whole point of the stochastic experiment that you’re taking on is negated by that, in my opinion. So like, What are you doing?

If you’re going through shooting film, processing it, printing it in the darkroom, and the final print is your final piece, I totally admire anybody that’s pursuing that. And the truth is, I do agree about the fashion accessory thing. I see people all the time posting images that are so subpar and feeling very proud …

Patrick Mitchell: … but it’s FILM! …

Dan Winters: … Yeah, well. And even so much so it was like calling that out, right? Calling out, “Shot on Ektachrome 160, blah, blah.” You know? And to me, it’s like, I don’t put “Shot on Canon 5D!” Or “Shot on Fuji, GFX 100!” That wouldn’t make any sense. I don’t know.

It’s all good. I mean, I think if it helps to foster someone’s love of photography or an understanding of that process, that historical process, I’m all for it.

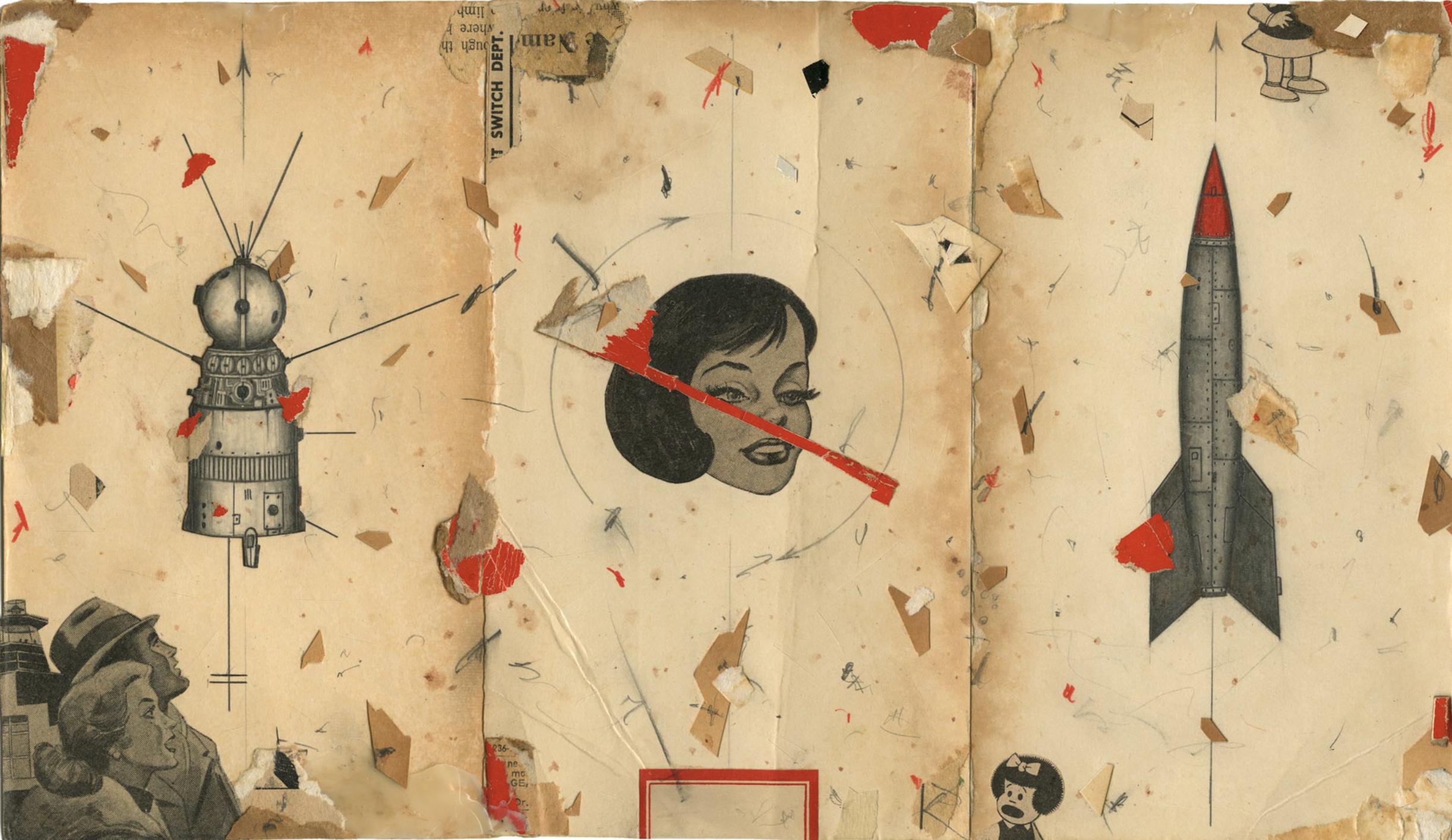

Winters is a rare double-threat—equally accomplished as a photographer and illustrator.

Patrick Mitchell: Unfortunately, we’re not going to be able to cover the breadth of your illustration career, which is really impressive. I saw an interview, I think it was at American Illustration/American Photography, where you were talking about Marshall Arisman, Brad Holland and Matt Mahurin—I will add Mark Ryden to that list because your studio looks like he could have designed it.

You were talking about the influence these guys had on you. And, as I was coming up, those guys were so powerful to me, too. Iconic and unique. Those were the guys on my Mount Rushmore. And when I started out, I revered them. And luckily I’ve been able to work with them over the years.

But when I heard you talking about them in that context, it was weird. I had this flash—I immediately saw you in that same group, even though you’re a photographer—and it really gave me a different lens on your work, which I think is—it’s photography, but it’s very illustrative and it’s got its style and it’s got its lighting and shadows. And it’s not weird at all to consider you in the same conversation with those guys.

Dan Winters: Yeah, they were giants for me as well. And I would include Mark Ryden. And I think that Brad Holland was—I think one thing was they were so consistent and they had such a singular voice—each one of them—and it was very succinct. And I think, as a creative director, as an art director, assigning one of those guys a job … I can only imagine how exciting it was to get that envelope, get that print, and get that image.

Because you knew that they were just going to rise to the occasion. Every time. I don’t remember Marshall Arisman ever phoning anything in. And his illustrations, they evolved, and they got more and more abstract and violent at times. And they were just such a great gift.

Well, that’s certainly a compliment, I will say, because those three guys were just absolute giants for me. And I always was a lover of illustration. I’ve drawn for years and I chose photography as kind of my primary pursuit, but seeing illustration in magazines always, always inspired me greatly.

And, you know, I went to the same junior college as Matt [Mahurin]. So I’ve known Matt for—I talk to him regularly—I’ve known Matt for 35 years. His career has taken on a lot of different twists and turns. He got into doing videos and films and stuff as well. But yeah, thank you. That’s an amazing compliment.

George Gendron: At one point again, in this interview they asked you about gallery shows, and you said one of the things you really liked about gallery shows was walking in and seeing very, very large prints of your work. And they asked if you have any large prints in your house. And you said, “Oh, I have one and it’s 40x60, but it’s not a print of my own work.” Whose work is it?

Dan Winters: I don’t have any of my pictures hanging. I have a house full of a photography and painting, but I think I have one print that my wife hung upstairs, but everything else is either historical or contemporary stuff of people I know, typically, that I’ve traded with or whatever.

George Gendron: Can we ask what print your wife chose to hang?

Dan Winters: It’s a picture of a boy in Cincinnati, behind a waterfall. George Krause made a photograph called The Submariner [1958] and it’s a little black boy behind a curtain of water. And he’s kind of protruding from it a little bit. Herb Ritts did some images that were similar to that. I did it at a public fountain in Cincinnati. And it’s a really beautiful print. It’s printed on Ektalure and toned with Gold 231 [gold chloride and ammonium thiocyanate], and then it’s varnished. And it’s a really rich, rich print. I had it and she’s like, “Oh, we should put that upstairs.”