The Fifth

A conversation with editor David Remnick (The New Yorker).

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT MOUNTAIN GAZETTE, COMMERCIAL TYPE, AND LANE PRESS

I want you to stop what you’re doing for just a moment and imagine we’re back in 1998. (Those of you born since then will have to use your imagination). We’re on an ASME panel exploring the future of magazines in the digital age.

The moderator, eager to get the discussion off to a lively start, turns to you and asks, “What magazine that we all cherish today is least likely to adapt and survive what’s coming?”

Without hesitation you blurt out “The New Yorker!”

The audience murmurs in agreement.

“The Atlantic!” someone shouts from the crowd.

More murmuring.

I’m not surprised. Neither is anybody else in the room. It’s almost three decades ago, and yet we’ve already headed into a new world of “nugget” media—and the total loss of our collective attention spans. Hell, magazines that feature 25,000-word polemics on topics like the squirrels of Central Park are already dinosaurs, even here in 1998.

It’s a bleak outlook for an institution—I’m talking about The New Yorker—that claims the following heritage:

It has survived two world wars and the Great Depression,

it’s been led by only five editors, ever, in its 71-year history,

it didn’t use color—or photography!—until its 67th year when a young, supremely talented, and controversial Brit took over in 1992,

and it’s now run by a former newsman who had never edited anything except his high school newspaper.

But here’s the thing: It’s 2024 and we’re looking at a decimated magazine business. Mighty brands and hot-shit startups alike are dead and gone—or running on fumes. The big publishers are divesting from print right and left.

And yet, there is a shining light.

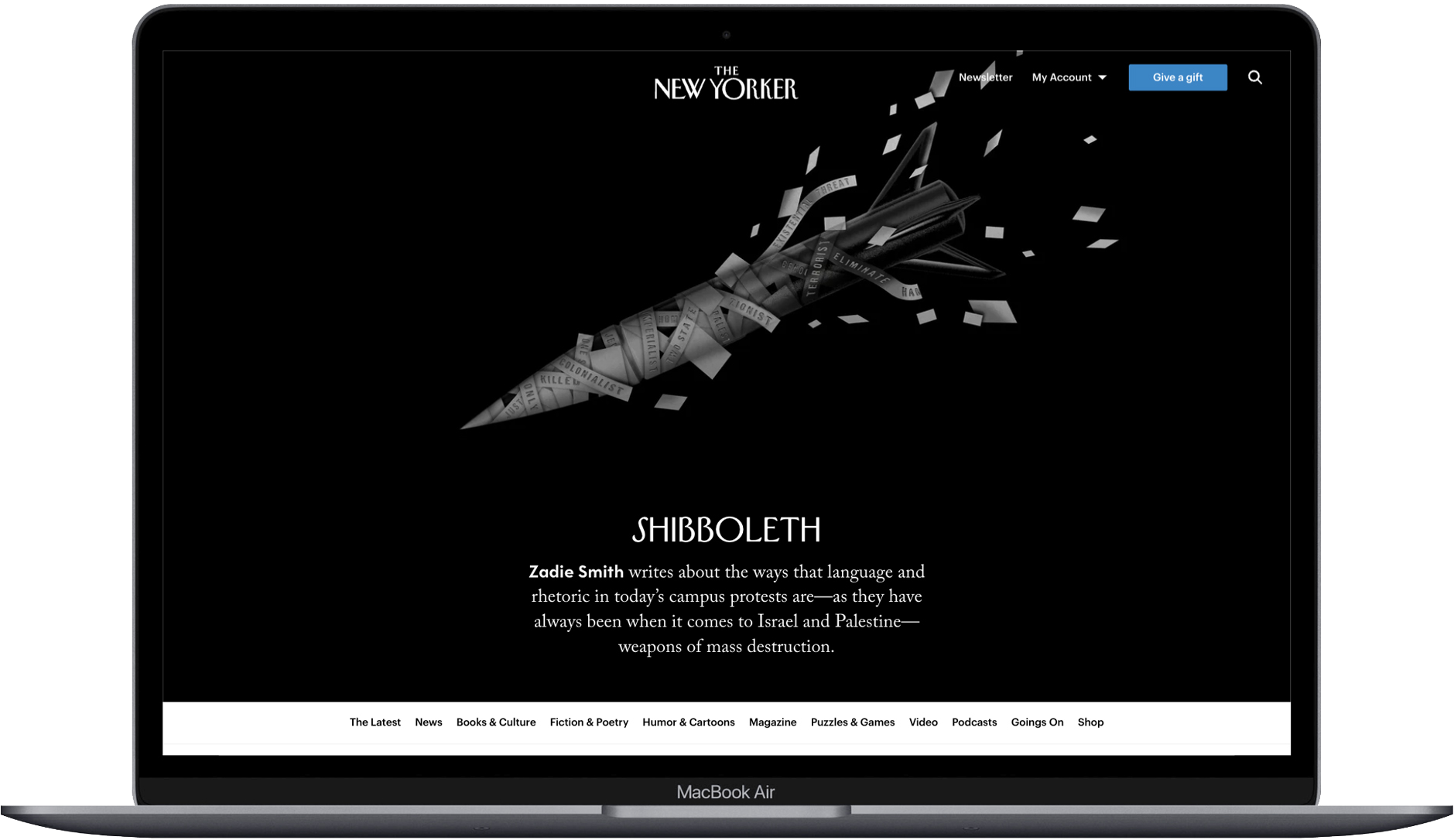

Today The New Yorker is busy preparing for its 100th anniversary, with that same newsman at the top of the masthead who has brought video, events, podcasts, print (a magazine!)—and even some branded pajamas—together with the most legacy of legacy brands to create a 21st-century media juggernaut.

Programming note: This is our Season 4 finale. On behalf of myself and our entire team, thank you for listening—and your passion for print.

Now, let’s meet David Remnick.

“When my feet hit the sidewalk in the morning, I feel like somebody in a ’40s musical. I want to click my heels. I love this city.”

Eustace Tilley, still quite the smokeshow at 99.

George Gendron: I want to start with the most important question of all, which is: You grew up in Jersey—what exit?

David Remnick: I grew up in Bergen County. It’s like northern Springsteen land. What can I say.

George Gendron: Me too. Exit 165, man. You were in Hillsdale.

David Remnick: Hillsdale. That’s right.

George Gendron: I was in New Milford and Oradell.

David Remnick: Oh, very nice. Very nice.

George Gendron: You went to high school at Pascack Valley High?

David Remnick: I did.

George Gendron: I went to Bergen Catholic.

David Remnick: Oh, you were far superior to us athletically, that’s for sure. Bergen Catholic, the rare times we’d play them, we’d get our backsides kicked.

George Gendron: And yet you were a regional school. So there’s no excuse for that.

David Remnick: “Regional school” is a fancy term for “we drew from two towns.”

George Gendron: I know. So just to come to closure about our common Jersey roots, just how much of your professional success do you attribute to having grown up in Jersey?

David Remnick: It’s nice of you to say it’s professional success. I don’t know what to say to that. What are the characteristics that are characteristically Jersey?

George Gendron: Tenacious? Scrappy?

David Remnick: I think for me, in all seriousness, what characterized it is its proximity to and its distance from New York City. In other words, it was a million miles away and 25 minutes away. And I wanted to bridge that 25 minutes and million miles as quickly as possible. And had my ear on and my eye on that place always. And now, at the age of 64, when my feet hit the sidewalk in the morning, I feel like somebody in a ’40s musical. I want to click my heels. I really mean it. I love this city.

George Gendron: I know exactly what you mean. I moved from New York in ’75 and I still miss it. I miss it in a way that’s extraordinary. So I’m going to stick with Jersey not as the location but as a period in your life. So you’re very young and I’ve heard you somewhere talk about, kind of, your, I think, your infatuation with magazines. And I’m assuming you were talking about Esquire and Rolling Stone. Maybe not The New Yorker, unless you were one of those savants that used to read The New Yorker with a flashlight under your covers.

David Remnick: I absolutely was not. And I came to magazines because we had a lot of them in the house. My father had a, I don’t know how to put this, extremely modest dental practice. And his office was attached to the house. And so I would, at night or on the weekends, I would sneak, through the basement and into his office, and lay on the floor of the waiting room, on the linoleum tiles, and read Highlights magazine and things like that.

As I grew older, I was completely taken up with what were the “cool” magazines. Time and Newsweek seemed awfully dull. But as I got a little older, the magazines that really knocked me flat were Esquire magazine and Rolling Stone, for obvious reasons. Counterculture was the news. And Rolling Stone had invented itself as the news of that culture, which seemed so far away and so tantalizing at the same time. And it was publishing all kinds of people as well as Esquire. And that just was not what was in The New York Times. That wasn’t what was in Time and Newsweek.

And it was really formative. The New Yorker was there too, but I didn’t know how to read it. Which is to say I didn’t know how to understand it. It seemed like something from Greenwich, Connecticut. Or Princeton, New Jersey. Which are two places I knew nothing about. It seemed distant.

George Gendron: Yeah, it seemed very grown up to me. Very grown up.

David Remnick: Yeah, and it didn’t have its feet firmly planted in the Church of What’s Happening Now, or what I thought to be the Church of What’s Happening Now. It had on its cover bowls of fruit and abandoned summer houses. It was not a language I knew quite how to cope with.

George Gendron: Although you still have bowls of fruit in summer houses on your covers.

David Remnick: Very often.

George Gendron: I’m kidding.

David Remnick: Very often.

George Gendron: We’ll get to that in a minute. It’s funny you say, “Okay, I’m reading Highlights.” But at the same time, you were also obsessed with Dylan’s “I Want You,” a song that was about nothing but lust.

David Remnick: Yeah, it was. The first album I ever bought that I ever spent my $2.99 on at EJ Korvette’s was something called The Best of ’66, one of those compilations. And it had really corny groups like Chad & Jeremy and Paul Revere & The Raiders. And it had this song on it, “I Want You,” by Bob Dylan.

And it sounded different than anything else. And he sounded different than anything else. And the lyrics were different than anything else I’d ever heard. That anybody had ever heard. And of course I didn’t know completely what to make of it. I didn’t know what to make of its emotions, physical and emotional, but it just hit home.

And I became, over time, so obsessed with him and his work, and his music, and his lyrics. And anything—or almost anything good that I bumped into until I was 15, 16 years old—came through the good offices of Bob Dylan. He would mention Cisco Houston—he would just mention American mythology, or he’d make a historical reference or a musical reference, and I would go seek it out. He’d mention Allen Ginsberg, I’d go to a church basement and buy, for 10 cents, a copy of Howl. Or he’d mention some seemingly obscure blues man and I’d find the album.

He was like the hub of the wheel, culturally. And when I look back on it, he was, you know, younger than 30 years old. He retired the first time when he was 25, which is such a weird thing to conjure when, you know, I’m 64 years old, for God’s sake. What an amazing figure he is. And he’s coming to New York next month to play—82 years old.

George Gendron: You’re going to go hear him?

David Remnick: What else would I do?

“If I were to put photographs on the cover of The New Yorker, I would just become like everybody else.”

George Gendron: You know, what you’re describing, this notion of the hub—I don’t want to get off on a tangent about this because I could turn our whole podcast into a conversation about this—but it’s really about how people really learn. Not school learning, but it’s about how people learn.

David Remnick: Well, look, I eventually—I am grateful to teachers that I had in high school and college, and I learned a hell of a lot, but the thrill of finding things on your own, and by suggestion, and through the radio, and through your record player, and what’s in the air has its own tantalizing thrill.

I noticed with my own kids something that I’ve decided is a law, and the law is the following: somewhere along the line, you have little kids and you play The Beatles for them and they love it. And as parents you become intoxicated and you think, The next thing I’m going to play for them, they’re going to love that too. No, that’s wrong. That’s wrong.

All little kids like The Beatles. It’s melodic. It’s magical. And then you play something else that you think they’re going to like, and they just, they don’t want to hear about it. They want to find their things on their own. And also, they have to drive you crazy. Their job is to push away their parents, not to invite every taste and auspices of their parents.

George Gendron: I think another effect of what you’re talking about though, whether it’s your kids and The Beatles as a point of departure, or whether it’s Dylan for you, is it encourages, and builds, and nurtures curiosity.

David Remnick: As I’ve gotten older and I’ve still followed that career, it’s very obvious that—and I don’t think this is an original thought—but it just is that Bob Dylan himself is a magpie. That his lyrics, his style, his thinking, his work is the result of all the things that went into his ears. Not only when he was very young, but starting with that.

And he was listening to 50,000 watt radio stations while he was a kid in Hibbing, Minnesota, and he was hearing blues. He was hearing hillbilly music. He was hearing first generation rock and roll. And that thrilled him.

So he found himself on a stage in his high school in Hibbing playing a Little Richard song in order to drive the principal crazy and for them to prematurely shut the show down. And then he starts reading things, poetry, the Bible, novels, watches movies, and it shows up in his work. He was a magpie. The voice is the result of a kind of magpie influence. And then it becomes him.

This is the story of American culture in large part. Look at Muhammad Ali. How did some kid from Louisville, Kentucky—from segregated Louisville, Kentucky—become that personality? Sugar Ray Robinson, Gorgeous George, street corner preachers, the Nation of Islam—we’re all that. We’re the sum of our influences, and then something magical happens if somebody has some originality in them.

George Gendron: There was a certain point in your life where you talk about wanting to be a novelist. And then due to, I think it was both your parents health issues, you felt that you should go out And earn, earn a living, a more routine income. And so you decide—

David Remnick: It just shows what a limited imagination I have—the idea that the way to earn a living was to be a … journalist?

George Gendron: —I was about to say you’re the only journalist I’ve ever talked to who said, “I went into journalism to make money.” Usually you go to Wall Street to make money.

David Remnick: And, of course, I do because I’ve been crazy lucky, but it’s not the first couch cushion you’d look under. And when I went to college—so I went to a fancy college [Princeton], and it was the first generation where people became investment bankers and became automatically rich. It’s not because they invented anything. It’s not because they became the CEO of some company.

They became automatically rich if they worked hard enough and stuck around at Goldman Sachs or JP Morgan. And I didn’t know what an investment bank was when I was in college. I thought investment banks were where you went with a little book and it had your savings in it and you took out 50 bucks. I didn’t know what that was. But that was the first generation of deregulation in the Reagan era. And we all found out pretty quickly.

George Gendron: So you get out of this fancy school as an undergraduate and somehow you miraculously get a job as a beat reporter at the Washington Post. How in God’s name did you do that?

David Remnick: It was a different era. It was an era of expansion, not of contraction. The Washington Post was running very high post Watergate In the late seventies, they were hiring—and not very diverse—but they were looking for bright young people to be reporters and editors and the rest.

And I was an intern there, twice, and finally stuck around as a night police reporter. Not a very glamorous job, but I learned a lot. And if I was looking for money well, hey, I believe it was 14,500 bucks in 1980. But on the other hand, my rent was only 350 bucks. So I was a very happy boy.

George Gendron: I had a similar experience. I got out of school in 1973 and got a job at New York magazine. And I recently found a pay stub. And I think they weren’t even paying me the minimum wage. I think I was making less than $6,000 a year. Now, I’m older than you, but at any rate, same thing, expansion. And New York was a startup—there was always more work than there were people.

David Remnick: The post was the hot shit newspaper because of Watergate, because of Ben Bradlee and Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein and All the President’s Men. And to be in that room promised to be something extraordinarily exciting. And despite the fact that I arrived just after the plagiarism scandal, the Janet Cooke scandal, caused a certain temporary depression in the newsroom, it really was an extraordinary place to be. I don’t doubt that it is now, but it was thrilling.

And after some bumping around, I ended up in something called the Style section, which was the section of the newspaper that was meant to in some ways imitate or draw from the kind of things that you were seeing in Rolling Stone and an Esquire. There was a great deal of freedom and maybe some more length and the guardrails are down a little bit in terms of voice, for a newspaper.

And I enjoyed that immensely. And then I got the break of a lifetime in the eighties. I was sent to Moscow as the second correspondent, the junior guy in the bureau. And the timing was such in 1988 that the world was breaking open. And I could have written ten articles a day, and they would have published them all. The interest was amazing. This was the period of Mikhail Gorbachev, of course.

George Gendron: Did you overlap at all with Celestine Bohlen?

David Remnick: Yeah, I did. I replaced Celestine Bohlen. We overlapped for about two weeks. She was very kind to me and showed me a few ropes, and then off she went home. And I worked with a guy for a little while named Gary Lee. And then he was replaced with someone named Michael Dobbs, who became very close to and his family. And we worked together for the better part of four years.

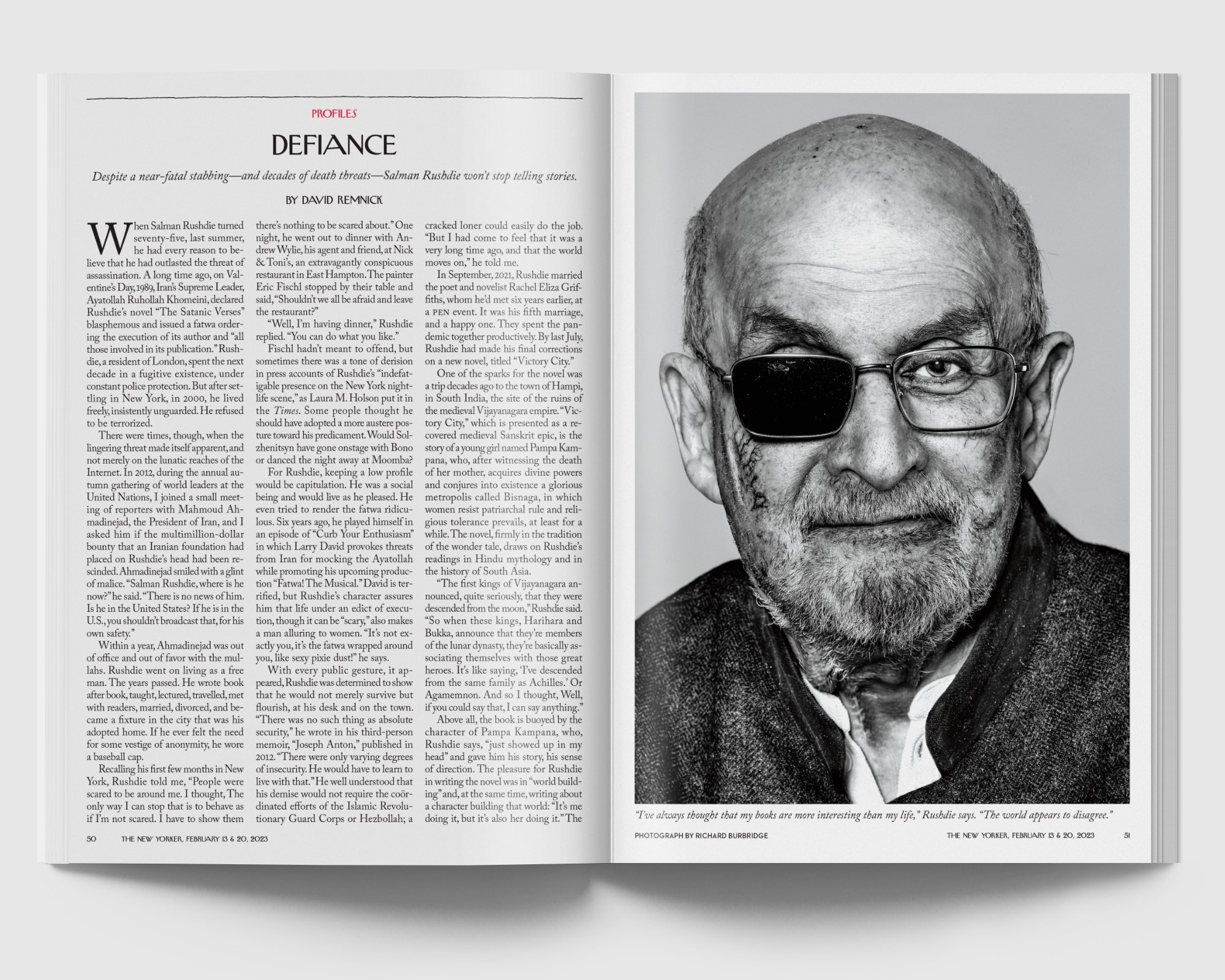

“As an editorial intelligence, I’m here to tell you that Tina Brown is really special.”

George Gendron: Celestine was extraordinary. Still is. But I want to go back to what you were talking about, which is, people probably know this intellectually, young people, but I’m not sure they really appreciate the kind of glamour that was associated with the post around this period, post Watergate.

David Remnick: That glamour emanated. Largely from its editor, Ben Bradlee, who was this combination of a ship captain and Humphrey Bogart. And he was a fabulous looking old wasp who wore Turnbull & Asser shirts, and could curse like a sailor, and had been the best friend of John Kennedy, which, in retrospect was probably a bad idea for a journalist.

George Gendron: Right.

David Remnick: And who basically built the modern Washington Post. First by building the newsroom together with Catherine Graham and her money. And then, joining on to the Pentagon Papers publication, and then emphatically with Watergate. He was a fearless, charismatic figure. And there have been some terrific editors ever since, but no one had the same sort of swagger and presence in a kind of cinematic way as Ben Bradlee.

Look at Marty Baron, who just finished at the Washington Post about a year ago. An unbelievable career. You know, with the Boston Globe, with The New York Times, and finally with the Washington Post. But not the same kind of personality. You know, if you see him in that movie about the Boston Globe?

George Gendron: Spotlight.

David Remnick: Spotlight. And Liev Schreiber gets Marty Baron pretty much on the nose. He’s kind of an anti-personality. He’s the sum of his judgment and steadiness. With Ben Bradlee, even Jason Robards could not match the charisma of the guy he was playing in All the President’s Men. It was thrilling.

And he was succeeded by somebody named Len Downie, who was less charismatic, but had all the, you know, strength and principle that Bradlee had embodied. I admire Len Downie very much, both as an editor and as somebody who had to carry that burden of succeeding someone who was like a comet.

George Gendron: Well, Bradlee looked like he stepped out of a ’40s movie, for God’s sakes.

David Remnick: He was a ’40s movie.

George Gendron: Somebody told me a story about you. I forget who it was, it might have been one of Ben Bradlee’s successors, about you and your wife going to the Hamptons.

David Remnick: I’ll tell you the story. I know what you’re referring to. I’m married to a woman named Esther Fein. We’ve been married for over 30 years—luckiest thing in my life—and had been in the same room with my wife, with Esther, and Ben Bradlee, who was then well into his eighties and we were then in our forties. And I was absolutely sure that if Ben Bradlee had lifted an eyebrow and gestured for Esther to go off with him to Morocco or Kalamazoo, off Esther would have gone.

George Gendron: Okay, that really sums that one up.

David Remnick: And I would not have blamed her. I would not have blamed her for a moment. Such was his charisma.

George Gendron: I feel journalistically about Clay Felker at New York magazine the way you do about Ben Bradlee, but Clay was never a threat when it came to my marriage.

David Remnick: Well, it was quite a stressor.

George Gendron: One thing you say about Bradlee that is really interesting is you refer to it as “the deep, dark secret” that Bradlee exemplified about the sheer fun of journalism. Adult fun. And how Bradlee just radiated the adventure of it all. I think at one point, maybe you’re talking to Alec Baldwin and you say he was driven by—he was driven out of his seat—by the story.

David Remnick: He was insatiable in wanting to know what was going on. You know, he exemplified that human desire to know, to be inside, to know what so and so was like, to know what was going to happen next, to know the secret behind the façade. And at the same time, it was fun.

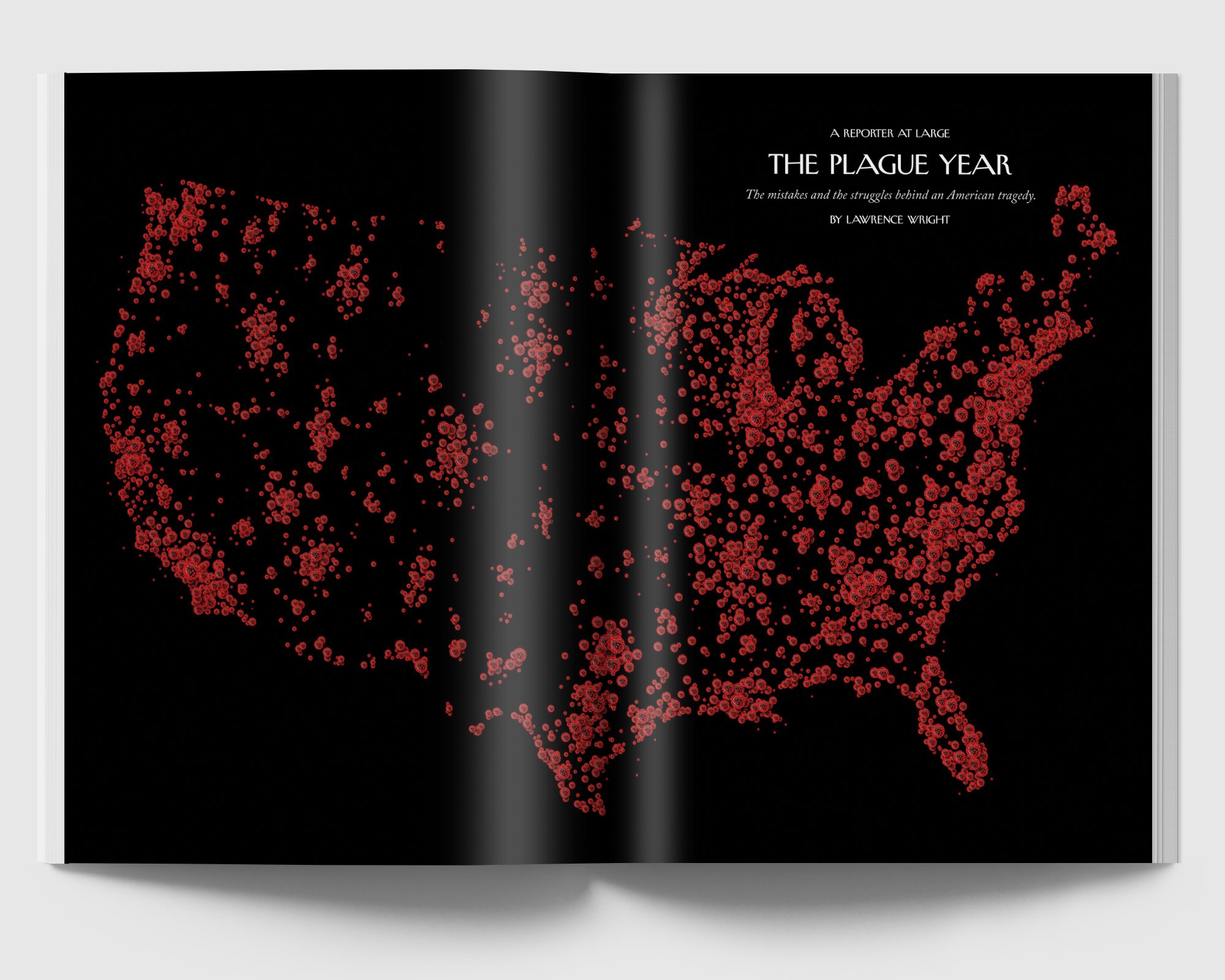

Look, in today’s world, there’s no question—why hide it—the media business all across the board is a struggle, a business struggle. All kinds of bad weather systems are flying in your face, whether it’s the change in the advertising business, or increased competition for subscriptions, or now AI, or the social media companies changing their algorithm and screwing all of us suddenly. It’s tough.

And so you’re constantly in meetings and you’re on Zoom and somebody will say, “Do you mind if I share my screen?” And suddenly you’re looking at a 40-slide presentation of just … numbers. And I try to imagine Ben Bradlee—and it’s necessary, by the way, it’s necessary. If you don’t get that right, there’s not going to be a lot of journalism. So I’m trying to imagine Ben in the world of Zoom and endless business meetings and acronyms and the use of the word “content,” I don’t think it would have gone well.

George Gendron: Adam Moss and I not long ago had a conversation where we said that if we had been born Trustafarians, which we decidedly are not—

David Remnick: Rich kids.

George Gendron: —rich kids. We would have paid to do the work of editing a magazine.

David Remnick: Since I’m still employed in doing that, I don’t want to give my overlords any ideas. So I’ll have a “no comment” for you on that.

George Gendron: Okay. Is it still fun for you with The New Yorker in this way?

David Remnick: Oh, yeah. Oh my God, yeah. Oh my God. It’s just that not every minute of every day is fun.

George Gendron: Of course not. It wasn’t ever, really.

David Remnick: No, and it’s a very big distinction to be drawn between editing and being a reporter, being a writer. Those two activities are, maybe they’re joined at the hip, but they certainly don’t overlap.

When you’re an editor, your concerns are across the board. They’re with the enterprise. They’re with individuals. They’re with groups. They’re with economic concerns as well as literary and journalistic ones. It’s a whole cast of things that can go terribly wrong or right in a given day. And it’s not just about you.

Whereas the writer—writers get knocked for being ego-driven, but of course they are. It’s their thing. They’re performing in public. That’s a very difficult thing to do. And I don’t blame the individual writers for not knowing every little detail of the whole business. Why should they have to do that? If they want to know, I’ll tell them. And God knows there’s a lot of writing about it in the press and so on.

But they’re very different activities. And I’ve tried with minimal success—only minimal success, George—to do writing while doing this job. And I have the illusion, and it’s only an illusion, that one day when I am not doing this job, I’ll have a whole new lifetime to have a fuller life as a writer. But I’m told—I read it in the Bible and I read it in the newspaper—that I’m not going to live forever. None of us are.

I made my choice at a certain point. In about 12 seconds. I was offered this job and Si Newhouse said, “I want to announce it in half an hour.”

I said, “Do I get to make a phone call?” It was like getting arrested.

He said, “Yeah.”

And I decided. And the decision was this: If I had been Philip Roth or Toni Morrison, or in other words, a writer of real consequence, I wouldn’t have taken this job in a million years. I just thought that I could make a contribution as an editor of The New Yorker, which had its established reputation and way of doing things and all the rest that I believed in, that I might be able to make an impact for the good.

“Most of all, we’re publishing writers that readers want to read.”

George Gendron: David, as long as you bring this up, it doesn’t happen every day that someone who hasn’t really ever been an editor becomes an editor-in-chief. Not to mention the editor-in-chief, the fifth editor-in-chief of The freaking New Yorker.

David Remnick: Yeah. And that’s a fair point.

George Gendron: Could you explain, could you pull back the curtain? How did that happen?

David Remnick: Yeah. No, I’ll tell you. Look, you invite me on, I’m going to tell you. I’ll answer your questions best I can. So you’re right. I had been at the Washington Post for 10 years and then I got an offer, when Tina Brown came to edit The New Yorker, to come write for her.

I’d written one piece for her. Two pieces, actually, for her Vanity Fair. One which ran and one which didn’t. So that’s not a very good percentage, 50/50. But anyway, I came. And at The New Yorker, I was thrilled. I didn’t think anything would match Moscow—four years in Moscow for the Washington Post—they were apples and oranges, but I loved it. I loved being a writer for that New Yorker, from 1992–98. And then, one fine day, Tina quit, and she went off to start Talk magazine.

And that put Si Newhouse in an unaccustomed position. Normally he decides when somebody leaves. In other words, he fires them or somebody retires. And there was no editor of The New Yorker. And he had to come up with an answer very quickly.

And I think he had a discussion with Graydon Carter. Graydon Carter wanted to stay put at Vanity Fair. It suited him better, according to him. Fine. And other people were interviewed, and I got called over to Si Newhouse’s office—the late Si Newhouse—who owned all of Condé Nast, the company that owns our magazine, as well as many other things. A billionaire, art collector, very cultivated person, a very quiet person.

And I was called to his office to be interviewed and I didn’t know what it was about. I thought maybe he wanted to hear from a writer to get an insight in the office and maybe they had a suggestion. But certainly I didn’t think he’d be insane enough to even consider a 39-year-old writer who had never edited anything other than his high school newspaper. (And not very well either).

And we had one discussion, and it was pretty fuzzy. And that was fine. And then the next day I was called back to the office. It was a Friday in July, a very hot day, 1998. And we had a slightly more direct conversation: What would I do if I were the editor, blah-blah.

And then the penny started dropping. Is he thinking about me? What is this? And I wasn’t entirely comfortable with that conversation. And so almost as a way to put an end to it after an hour or so, I said, “Why don’t I write a memo for you over the weekend?”

“Okay … mumble, mumble.” And we left.

Little did I know that he was also talking with an amazing editor named Michael Kinsley, who had edited Harper’s, who had edited The New Republic twice, with great distinction. An extraordinary, short form writer, essayist, political thinker, and editor of The New Republic in the eighties, at its real zenith. You could argue with this, that, or the other thing about it, and that’s another discussion. But an extraordinary journalist who had taken on the job of starting Slate, which was the first high-powered internet magazine of its time.

So he was living in Seattle, near Microsoft, which owned it. And Kinsley flew in on Saturday and met with—and I’m only telling you this because he’s told the story, and I believe him—but Michael came in and spoke with Newhouse on Saturday, and they came to an agreement, a tentative agreement, that Michael would become the next editor of The New Yorker.

And I’m here to tell you, if that had been the case, I would have been perfectly happy. Michael Kinsley is, you know, a person of real substance. And the next day, there was a dinner with the Newhouses—that generation of the Newhouses—and Michael Kinsley. And after the dinner, Michael came back to his hotel room to get a message from Si Newhouse that he had changed his mind.

George Gendron: Wow!

David Remnick: That he decided not to go forward with it. I do not know why. Whether it had to do with some vibe he got about him editorially, or personally, or—subsequently, we learned that Michael’s health was not good—I don’t know. I don’t know. I’m not sure that even Michael knows why. And Michael’s still very much alive and well. Well, he’s got Parkinson’s, but he’s very much around. He’s married to a woman named Patty Stonesifer, who’s been the CEO of the Washington Post lately. And I knew nothing about this. And then the next morning I got a phone call from the late Steve Florio, who very decorously said, “Come over to Si’s office. And don’t fuck it up.”

George Gendron: Oh, don’t you love that?

David Remnick: I was literally getting my hair cut when he called me. So I came over and there was Si Newhouse and he offered me the job. And he said, “I want to announce this in an hour.” And I called my wife and she said, “If you hate it after a year or two, you can always quit and go back to writing.” And that was 25 years ago.

That’s the story, George. What can I tell you.

George Gendron: That’s a great story. I’d never heard that before.

David Remnick: I don’t make any secret of it. And I tell it only because it gives an indication of how different it is from The New York Times. The New York Times is a real institution in that people go up the ladder and there’s competition and there are rivals and all this kind of thing.

Here, there was nothing of the kind. There was an editor. There was no thought to her having a successor because she’d only been the editor for five or six years. The New Yorker had been through a succession crisis when William Shawn, as brilliant as he was, had a very hard time dealing with the notion of life after him.

And he was put out by Newhouse when Shawn was about 79 and replaced by Bob Gottlieb. And Bob Gottlieb did the job for six years and that ended and Tina was brought in. So nobody really expected this. Tina kind of caught everybody by surprise. At least she caught me by surprise. And I got along great with her and still do.

George Gendron: I’m curious now, having told that story, what were the advantages of never having been an editor and taking over a magazine?

David Remnick: None.

George Gendron: None? Okay.

David Remnick: None. I can’t think of one. I didn’t know how to run an institution. I didn’t know how to edit. I didn’t know how to organize the place. Traditionally, people—somebody like Adam Moss, say—when he went from The New York Times Magazine to New York magazine, he had his people, he had experience, he had a circle of trusted senior editors or money people, whatever.

I had goodwill. I worked in the office five days a week. There was a time when people did such a thing. And so I knew people at The New Yorker and I had their goodwill and they brought me along like a toddler.

George Gendron: Well, I was about to espouse my theory of the competitive advantage of ignorance, but forget that.

David Remnick: No, no. It’s too much the big leagues for there to be a competitive advantage of ignorance.

Remnick hosts The New Yorker Radio Hour podcast, a co-production with WNYC Studios, which features interviews, profiles, and humor. Top: The New Yorker has gone all-in on podcasting.

George Gendron: Okay, I want to move ahead, but I have to ask a question that any listener is going to be thinking right now, which is, what was the staff reaction when you were named editor? We know what it was when Tina Brown was named editor. Did anybody threaten to quit?

David Remnick: Well, we know what—I think if you’re implying that it was negative when Tina became editor, that’s not true. It was mixed. There were some older writers, particularly of a kind of middle-older generation that rebelled, that were not happy.

And then a lot of people were, “Let’s wait and see,” and had the decency to be there. I think there was some reaction that was just purely sexist, to be perfectly honest with you. And I think some were alarmed because she was an “outsider.”

You know The New Yorker risks, over time, being too insular a place. And I think somebody coming in from the outside, from a magazine deemed by some to be excessively flashy, or Hollywood, or something like that, didn’t take her seriously. But as an editorial intelligence, I’m here to tell you that Tina Brown is really special. And she broke some crockery, but she also intended to break some crockery. And I think some crockery needed breaking too.

And she made my life, I’ll be very frank, easier, because The New Yorker had, in some ways, ossified. There were a lot of people around who were only nominally writers, because they weren’t really writing. And it was both a difficult thing on a human level and an economic level to shift the staff, to revive it.

And when you do that, you hurt feelings, and drama ensues, and not everybody you hire works out to be what you had hoped, and there’s a lot going on. And somebody, like Garrison Keillor, dumped on Tina from a high height before she published ten issues. I didn’t think that was fair.

George Gendron: There were people dumping on her before she ever published anything. So now I want to fast forward here in the interest of time. Today you preside over a New Yorker that includes print, the website, The New Yorker Radio Hour, video and short film, The New Yorker Festival, the shop—

David Remnick: If you want a New Yorker t-shirt, I’m your guy to come to.

George Gendron: I’m going to ask a question that a dear friend of mine asked me to ask—and I’m definitely not going to identify her—do you sleep in The New Yorker PJs from the shop?

David Remnick: I do not. Let’s leave it at that.

George Gendron: Yeah. Okay. Oh by the way, you have a softball team.

David Remnick: Of course we have a softball team.

George Gendron: And I promised Gloria Steinem I would ask this. Is the team any good? And who dominates the league these days?

David Remnick: You promised Gloria Steinem? I don’t know that we’ve played Ms. I don’t go to all the games by any stretch of the imagination.

George Gendron: We did. At New York magazine I was on the softball team and we got our butts kicked by the Ms. team.

David Remnick: Can I tell you who the best team consistently year after year in the last 20 years has been? High Times. High Times. And believe me, they came as advertised. I mean, the weed smoke that was coming from the other side of the field was impressive. And yet they smoke the ball. And we—I don’t think The New Yorker was alone—we always lost to them, 15–2.

George Gendron: That’s because they were relaxed out there.

David Remnick: They were, exactly. Exactly.

George Gendron: I asked Gloria—

David Remnick: I give them credit. I give them credit.

George Gendron: Unlike High Times, I said, “Did the Ms. magazine softball team have a secret superpower?” And she said, “Yeah, of course we did.” And I said, “What?” And she said, “Bella Abzug on third base.”

David Remnick: I would pay big money to see Bella Abzug at third.

George Gendron: Me too. Evidently, she was an extraordinary athlete. So you have this incredible variety of offerings, and yet, in a wonderful conversation you did with Alec Baldwin, he says to you at one point, he’s talking about editing, and he’s, “Well, when you’re working with young writers, you don’t do line-editing and worry about the right adjective and adverb?”

David Remnick: I’m line-editing right now! The very young writer, John McPhee, who has a piece in the magazine week after next.

George Gendron: Boy, does he need help.

David Remnick: Oh my God, what a mess he is. Thank God I’m here to rescue him from his egregious mistakes.

George Gendron: But then you say to Alec, “Yeah, of course I do. Everything matters.”

David Remnick: But here’s the thing. That is exceptional. I read everything. Not everything that goes right online. I want to be accurate here, you know, because the volume of what we publish is much greater than it was when we were only doing a print magazine. There are things that go online before I read them. But I’ve had to learn to be a trusting soul.

George Gendron: Do you have a newsroom?

David Remnick: Michael Luo and Monica Racic and many more who run the website, we’re mushed together. It’s not like the website is in North Dakota and the print is in South Dakota. It’s increasingly well-integrated and that’ll only increase more with time, a short period of time. I read everything. Do I single-handedly close a lot of pieces during the course of the year? No, I don’t.

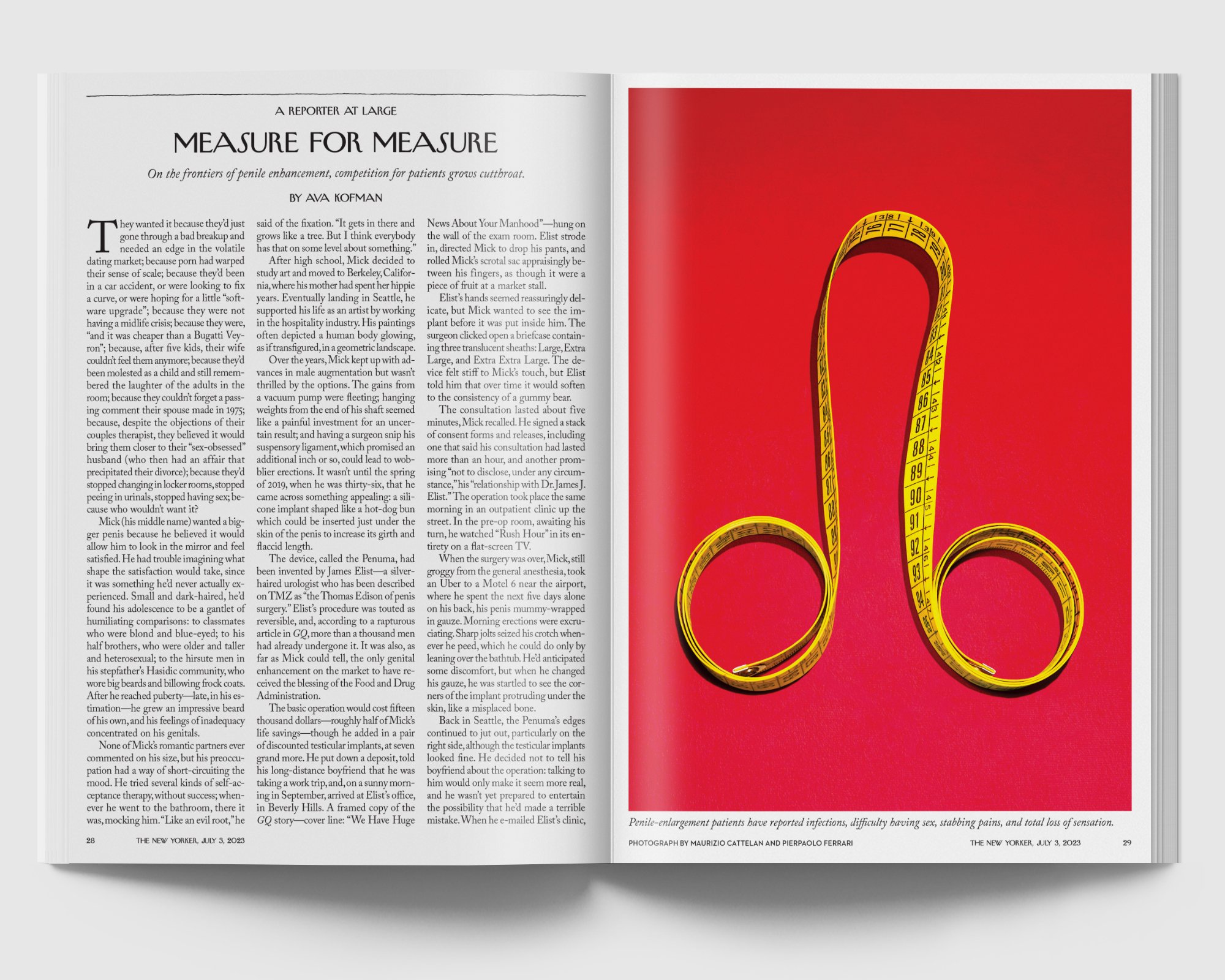

George Gendron: But do you still pick the cartoons?

David Remnick: I do. The way that works is Emma Allen is the cartoon editor. She and a couple other people read hundreds of rough sketches a week. She whittles it down to about, I don’t know, 50? And then sometime in midweek, we have an hour long meeting or so, in which we go through those 50 and we get to about 20.

So I’m the decider going from the 50 to the 20. But she’s sitting there with me and I ask her advice and she, you know, puts her thumb on the, on the scale. And, she's terrific to work with.

“If I had been Philip Roth or Toni Morrison, or in other words, a writer of real consequence, I wouldn’t have taken this job in a million years.”

George Gendron: What’s been your favorite cartoon during your tenure? Or is that impolitic to ask?

David Remnick: It’s extremely impolitic. It is like, um, George, who is your favorite child?

George Gendron: Yeah. I do have one, but I’ve just never said.

David Remnick: I mean, I have favorite New Yorker pieces over time, over the years. God knows there are a lot of them. But you know, if I’ve learned anything since that July of 1998, it’s that you don’t answer questions like that.

George Gendron: Yeah. No, I got it. I wanted to give it a try. We just did a podcast, a great one, with Barry Blitt. So I was rooting for Barry.

David Remnick: And Barry Blitt, who has done in the past—certainly in my time—the lion’s share of political covers, is a guy who presents, certainly on a podcast or in conversation, a kind of arch, schlemiel-like presence. But that’s all facade. He is all steel and iron and wit.

George Gendron: But that persona, he’s really refined that.

David Remnick: He’s got it all going on there.

George Gendron: Okay. Now, as long as we’re talking about cartoons, it raises the question of the visual identity of The New Yorker.

Speaker: Yeah.

George Gendron: Within magazines and then the larger culture as well for some time now, thanks, not exclusively, but very much to Apple, and Steve Jobs, and Johnny Ive, design has been in its ascendancy. And designers in some cases in large consumer companies now demand to be and are included at the strategy table. It’s not just a functional role. I’ve never heard you talk or I’ve never read anything you’ve written about design and I’d love to hear how you think about that at The New Yorker.

David Remnick: It’s a good question. I think something like The New Yorker, whether it’s in the print age, or now in a kind of multiplatform age—print, digital, on your phone, on your screen, in the air, you know, projected against the Empire State Building, whatever it might be—needs to still be instantly recognizable. You need to glance at it and know as quickly that it’s The New Yorker, as opposed to something else, as you would on a football field and know it’s the Giants, as opposed to the Philadelphia Eagles.

I think of the many things that we are happy to inherit. We have these signifiers. We have the Caslon typeface. We have the Irvin typeface. Irvin is The New Yorker logo. And then Caslon is the body type. It’s very distinctive. You see it from across the room and it’s The New Yorker.

If I were to put photographs on the cover of The New Yorker, I would just become like everybody else. Have I ever been tempted? Uh, yes. But, but no. Because that would be giving away the store. That would be the height of foolishness. Now, how does that then translate to other media? How does that translate to other media as art changes, as styles change, as the staff becomes different, more diverse, all the rest?

Well, it does change. And people die and new talents come along. I just—I swear to God, George—a month ago, I had a speaking engagement. And somebody asked me why we don’t run any more Charles Addams drawings. She loved Charles Addams when she was young. And I didn’t want to be flip or dismissive or mean.

George Gendron: But how do you not be?

David Remnick: Immense restraint. Immense restraint.

George Gendron: So what’d you say?

David Remnick: But it’s nothing new to me. When I first started, I would get notes, “How come you don’t run Mr. Thurber anymore?” Well, to quote Joseph Conrad, or to twist the quote, “Mr. Thurber, he dead.”

George Gendron: I remember Conrad. I never came across that Conrad quote.

David Remnick: “Mr. Kurtz, he dead.” Yeah. But we know this. And it is true that the style of cartoons generically has changed. There are fewer, fully, lushly-inked, cartoons in the style of Peter Arno, or Addams, or people who are wonderful.

And do I miss some of that? I do. I have to confess. I don’t want to be old-fashioned, but that kind of lushness and attention to style, as opposed to the more neo-primitive, whatever you want to call it, the people that are—you look at Roz. Or imitators of Roz. I think Roz Chast is a kind of genius.

Remnick interviews director Spike Lee at The New Yorker Festival

George Gendron: Oh my God. Is she ever.

David Remnick: Genius!

George Gendron: I wait for her to post on Instagram.

David Remnick: I wait for her every week. So it’s good that we have certain things that don’t change or that if they change, it’s because we’re playing around with it, like Eustace Tilly. But everything else is up for grabs. It drives me nuts to hear somebody refer to “The New Yorker style,” a “New Yorker story.”

I just think that’s lazy thinking. I think it’s bullshit. It’s like saying, “Okay we published short stories by George Saunders and by Edna O’Brien. Are they the same?” I think that’s crazy. Or a nonfiction, is Janet Malcolm the same as Evan Osnos or Hilton Als or Vinson Cunningham? No.

What I admire most about The New Yorker is that, yes, we pay attention to subject and we want to get to certain subjects over time. But most of all, we’re publishing writers that readers want to read. They see the byline as quickly as they do the subject.

And that’s the appeal. I want to read what Parul Sehgal has to say. I want to read what Rachel Aviv has to say. Or Evan Osnos, or Julian Lucas, a wonderful young writer, joined the staff just a year or two ago.

George Gendron: I have a slightly different reaction, because of my distance from The New Yorker, but when I hear people say that I think of it as a sign of, kind of, intense loyalty and passion for the publication in a way. When I think of The New Yorker, I think of Adam Gopnik, given my interests. I think of Elizabeth Kolbert.

David Remnick: But that’s natural. It’s because they’ve been around for a while. You know, Anthony Lane’s been around for a good long while. So has Adam Gopnik or Hilton Als and any number of other people. Calvin Tompkins is 96 years old and he’s writing absolutely fresh and wonderful profiles of artists. Remarkable person. John McPhee, I’m editing this week, is 92. Roger Angell died only recently at 101 and was writing almost to the end.

George Gendron: Yeah.

David Remnick: But a magazine can’t only exist on its elders. Although we value them beyond measure, I am constantly reading other places and other people to see what’s happening, who’s new—what does this person have to say and how does she say it?

And quite frankly, the diversity in the magazine is essential. When I got to the magazine, I came with Hilton Als and, I guess, Skip Gates also wrote periodically for The New Yorker. Jamaica Kincaid. I mean, it was really parlous. It was bad.

I’m not saying we are anywhere near where we should be in certain ways. We don’t have enough of this or that, but it’s vastly different. Cartoons are the same thing. It’s no longer, you know, like the cast of the Friars Club and that’s important.

The New Yorker online: Non-stop fun.

George Gendron: You just talked about when you got to The New Yorker with Hilton Als. Let’s go back and imagine, it’s maybe two years into your tenure there and you show up, I don’t know, at an ASME event or at the Columbia School of Journalism and somebody’s speaking and they predict that 25 years into the future, the two leading magazine properties in the digital age would be what my buddy, the producer of this podcast refers to as a designer, as the “eggheads”: The Atlantic and The New Yorker. Can you imagine how the audience would have reacted?

David Remnick: I don’t know how they would have reacted. I do know—and I’m very proud of my former colleague at The New Yorker and now the editor of The Atlantic, Jeff Goldberg, I think he’s done a terrific job. But what I know best is The New Yorker. I also know, just as democracy is fragile, these institutions are fragile. I look at The New Republic, and how great it was. Complicated, much too male and too white, and so on and so forth. But it really was an exciting institution, and it got turned upside down, and not for the better, in an instant.

I think it’s finding its feet again now, as a more Left magazine, and an interesting one. But these things are not forever, necessarily. In fact, most of them are not. When my parents were middle-aged and younger, Life magazine was at the center of their middle-class and middle-brow cultural existence. Life magazine, and to a lesser degree, Look magazine, and Time magazine, and Newsweek magazine.

Life magazine doesn’t exist, neither does Look, neither does Newsweek really, and Time is on the bubble. And it’s important to think about that for somebody in my position or the people that own the place or the CEO, Roger Lynch, who I think has done a stunning job of getting Condé Nast on his feet, and finding a way toward the future. A stunning job, actually. Great partner. But it’s important to remember that. Everything is fragile.

George Gendron: I want to come at this from a slightly different perspective. There’s been lots of talk among those of us in the media about the renaissance taking place in radio and television. Can you imagine a similar renaissance in print? Any idea where we might look for that type of renaissance to begin?

David Remnick: I’m 64 years old. I grew up with print. I love print. And yet you’re talking to somebody who does not any longer get a print subscription to The New York Times. I never would have thought that would happen even as recently as five years ago. But I read The New York Times no less intensely than I did all my life.

I think a print New Yorker is a way better technology than a print New York Times because of the whole giant broadsheet problem. What I care most about with The New Yorker is what’s in it, what’s on it, what’s said, how it’s said, how it’s edited, how it’s written. If somebody chooses to consume it, to read it, to love it, in print, digital, in both, I’m happy. That’s the most important thing.

Long live Print Is Dead. You choose. The audience is going to choose that for us. What I want to do is make the best possible New Yorker and see The New Yorker thrive long past me. And I know my colleagues feel the same way. And it’s an absolute privilege to serve that cause because that’s what I think it is: a cause.

The New Yorker will be celebrating its 100th anniversary next year. For updates on their plans visit the website or follow them on Instagram @newyorkermag.

More from Print Is Dead (Long Live Print!)