What’s Black and White and Red All Over?

A conversation with designer Roger Black (Rolling Stone, Esquire, Newsweek, New York, Smart, more).

Roger Black is a pioneer. His art direction of iconic print brands and high-profile redesigns, his early embrace of digital publishing technology, and his typographic innovations are hallmarks of a 50-year, trailblazing career.

He’s refined his design mastery at publications ranging from Rolling Stone to Esquire to Newsweek to The New York Times Magazine. He’s written books and started companies. He’s worked for clients on every continent.

And now, at 73, Black’s focus has shifted to type. More specifically Type Network, a font platform launched in 2016, where he serves as the company’s chairman.

Black’s design legacy not only includes memorable makeovers but also the fundamental need for an underlying reason and purpose behind them, often sophisticated, always functional. Throw in his signature color palette — red, white, and of course, Black — and you’re in business.

All that said, Black preaches that the true DNA of a successful brand identity is its typography.

We talked to Black about why he left home in the third grade, how an early blunder almost cost him his publishing career, what it felt like to follow in his mother’s footsteps at the New York Times, what he thinks are the five best-executed magazines of all time, and about why he’s always on the move — and where he’s headed next.

Patrick Mitchell: In his in-depth article about you for New York magazine, the notorious Michael Wolf said of you, “The goal he seems to have set for himself is to design, practically speaking, all magazines. And to a large degree, he has succeeded. Certainly he has designed more magazines than anybody else. He may have also made more money from magazines than any non-owner.” There’s a lot not to unpack there, but I think it’s fair to say that most people in our business would say that's a pretty accurate picture.

Roger Black: Well, it’s a fairly low bar at the end to say that I made more money than non-owners, because most of the owners that I know went broke.

Patrick Mitchell: But you’ve taken the magazine art director position to a place few of us have ever seen. Was that your plan?

Roger Black: I think every art director, every designer, whether they spend a lot of time on it or not, looks at everything as a subject for redesign. You look at anything, and it could be architecture or industrial design, and you say, “I could do better than that.” I mean, nobody would be a designer if they didn’t have a certain amount of ego. And some of us have a lot more ego than probably the customary share. So that’s probably why I ended up doing so many magazines, that I just thought they needed to be done.

And as you know, I started a few, too, that weren’t fresh designs, but the thing that I note is very early on — well, fairly early on, I was probably in my early thirties — was that I wasn’t really designing pages much anymore.

I was designing systems for designing pages. And that was what I was most interested in. How do you set up the rules and formats? (That’s what we called it in those days, “formats”) …

Debra Bishop: … We still call it formats!

Roger Black: … And there would be a list of type, and we would do an illustration- and photo-stylebook and engage with photographers and illustrators, help hire staff photographers — if we could convince them to do that. And that became really interesting to me. And then it became a business.

People kept saying, “Could you do that? Could you do that?” And then I kind of went nuts and started other studios because my language skills are typical American. That is to say, I get through English probably not that well. And the other languages are pretty blurry. I can read the Latin languages, but if you came up and started talking Portuguese to me, I would have to use Google. Fortunately, Google has that automatic translation now, so your phone could help you.

Patrick Mitchell: So along those lines, I want to ask you, what is a creative director? Because I think, as important as your design work is, your true legacy is redefining the boundaries of where you can take a design career.

Roger Black: For one thing, creative director to me is a title, an advertising title. I think that Milton Glaser had it right when he tried to change the title to “design director” rather than art director. I mean, Milton, of course, was the greatest art director in history, in many respects, and certainly had the most wonderful studio with Push Pin, with Seymour [Chwast]. But he thought of the work that he was doing at New York magazine was more about design than art direction. And he liked that title. And it was slowly adapted or adopted. And I used it in a number of places, but then quickly I just became a consultant and there were other people who were design directors.

But I think that the point of being an art director, creative director, or design director, whatever we called it, is to be the agent for the customer, for the reader. To figure out ways of getting that person into the product — as they now call it — whether it’s a website, or an app, or a magazine or a newspaper, whatever it is.

And I only work with really text-based publications or products, because that’s what I know. If I knew more about video, I would certainly do that, but I don’t know much. And the thing is that most designers, and I’ve said this many times, think of themselves as artists.

One way of defining it, I’ve always said most art directors are frustrated artists or frustrated photographers. And there’s the typical stories that mom sent you to art school but then she said, “You got to get a job and maybe you should take some design courses while you’re there.”

So they came into the scene really being agents for photographers and illustrators. And the typography was thought of as art “graphics,” not as a conveyor of meaning. And my feeling was I didn’t want to be an agent of the photographers and illustrators. In many cases, I was trying to instigate them, trying to get them going, to try to get them excited, but I was also their adversary as well as their advocate. I wanted to challenge them. I wanted them to bend to whatever the publication needed, as opposed to what they needed, and also what the subject needed.

But anyway, the thought is that the role of an art director is really to get people into reading, in my view. And that means you got to make it easy to read. You have to give clues, you have to give summaries. No one’s going to read everything. You have to make it digestible and comprehensible and interesting. If somebody spends five minutes with your website, whatever it is, they should feel a little satisfaction. “Oh, I got something out of that. That’s cool. I’ll go back,” because that’s what you want. We want loyalty. And now of course they measure all of this, but we don’t just want good session time. We want return. We want subscriptions.

And that’s helped actually finally began to define what the digital publication business model is. It's subscriptions. So we should be working on that.

“I think every art director, every designer, whether they spend a lot of time on it or not, looks at everything as a subject for redesign. You look at anything, and it could be architecture or industrial design, and you say, ‘I could do better than that.’”

Debra Bishop: But do you consider yourself an artist?

Roger Black: I’m not an artist. I can barely draw. You don’t want to see anything I draw. It’s pathetic. I was an okay photographer, but my best pictures were taken with completely manual cameras. And my brain just isn’t fast enough to do all the calculation of shutter speed and aperture opening and stuff. And all my good pictures were taken by sure luck. I would say that’s probably a great photographer, is one who has a lot of luck, knows when luck's going to happen.

Patrick Mitchell: So looking back though, in the first grade you made a blunder that might have ended an otherwise promising career in the media. Can you share that story?

Roger Black: Well, my dad was an architect and his office was at home. His name was JJ Black, and he had a Ditto machine, which old people know was a spirit duplicator that was used a lot in schools for teachers to run off assignments for tests and things. And it was an easier thing to use than a mimeograph, which involved a stencil that you had to cut, usually just with a typewriter that didn't have a ribbon in it, but the Ditto machine was a heavy wax carbon back that you put on the back of a piece of paper and then you could draw or type on it and it imprinted on the back, unfortunately backwards. So then you could put it on this cylinder and little bits of alcohol would make it moist enough to make an impression on one sheet of paper without rubbing it all off.

And, of course, we did.

Sometimes we used too much to this “spirit” and it would get kind of messy. And my dad had discovered that you could get different colors than that usual blue that they printed everything with. And it was very fun, kind of very milky, dusty-looking crayon colors. So by changing the batch, you could draw and get a color image.

So I started using this in the first grade to print my own newspaper, which was called My Fun Reader. And it was aimed at My Weekly Reader, which was ... it may even still exist. It existed for a long time and was just filled with the most boring pap that you could imagine, but it was made for first-, second-, and third-grade readers. I think they may have had different editions as you got older.

Anyway, it was terrible and I said, “We could do better than this.” So we tried. And then the thing you’re alluding to is that I got in trouble because I started doing reporting and I had very little understanding of the conventions and rules on this [laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: You didn’t have your own libel lawyer.

Roger Black: I had no advice at all on this! Except for my friends who were helping me: Betty Legette and Johnny Ernest, and some others. Anyway, so I found out that two doors down, the lady had become pregnant and I thought this was wonderful! There’d be another little kid! And I printed that.

And my mother went berserk! And I said, “But it’s great news! And everyone knows about it.”

She said, “Yes, but she’s not married!” And my father threatened to take the press away. Well, actually he did. He closed it down and then I never got it going again.

Patrick Mitchell: They shut down My Fun Reader?

Roger Black: I know.

Patrick Mitchell: “Ladies and gentlemen, we’d like to announce that this is our last day of publishing…”

Roger Black: Yeah, we didn’t even get that opportunity. I don’t think it was widely missed. A few people in James Bowie Elementary may have noticed it was gone…

Debra Bishop: You once said, “I pretty much had my life figured out for me by my mother very early on. I was not going to be around very much.” And sure enough, you were shipped off at the age of ten — TEN! — from rural West Texas to a posh boarding school in midtown Manhattan. You said your dad was a workaholic and your mom kept herself very busy too. Why do you think they chose this path for you?

Roger Black: Well, my mother’s reason was that she had — one of the things she organized in my hometown, Midland, Texas, was the PTA. I had three older sisters and she got involved with ... they were in school and was an advocate for better schools in town and mobilized the other mothers, really. They were the main participants to push the school board in the city to spend more money and get better teachers.

And she pretty well was able to select my grade school teachers, first, second and third grade, fourth grade. And then she realized in the fourth grade that there was nobody in the fifth grade that she thought was any good.

And she said to me, “I don’t know what we’re going to do with you. In England, they go to boarding school at your age. So let’s look around.”

So she took me to the New Mexico Military Institute, which, remember Donald Trump went to a military boarding school? It was like that. And it was made to look a little like West Point. It was kind of Gothic. It was in Roswell, New Mexico, which is actually a much nicer town than Midland at the western end of the Permian Basin Oil Field. I always wondered why people put Midland where it is when they could have had their office in San Angelo or Roswell, which are both really interesting geographical places to live.

Anyway, Midland is like living on the moon. It’s flat. Anyway, I said, “I will not go to this school.”

And she said, “What would you do?” And I said, “I would run away.” So I pretty much do what I would do, and my mother said, “Huh, that's not going to work.”

And just by coincidence, she went most summers to visit her mother and family in New Jersey. And she saw an ad in The New York Times Magazine, which had an ad for St. Thomas Choir School, which was still accepting — this was in May — it was still accepting applicants for that year, that September. And she called them up and we went in. She took me in and it was kind of cool.

And I liked the idea of moving to New York. I always thought that my parents were thinking of moving back to New York. They met in New York and then moved to Texas when architecture came to a big stop in the early thirties. And they moved in 1932 to West Texas. And they always talked about New York and my mother always went every year. My dad often went. So I was like, “Yeah, I’ll go here. This looks great.”

Debra Bishop: Were you scared?

Roger Black: Not at all. I don’t remember being scared for a minute. I should have probably been scared, but I was excited. I was happy. I felt like this is it. I’m ready. I’ve got my suit, my overcoat. And I headed off in the airplane.

Debra Bishop: Was it a culture shock at all?

Roger Black: I knew New York well enough. I think the culture shock was the change in environment, from living at home with my family to a boarding school with 40 little kids, very carefully taken care of. It still is. It’s an amazing school.

At that point, we all sang in the choir. My voice didn’t change until the summer I was 13, so I made it all the way through school singing in the choir. But it was an amazing school. They had plenty of money and they had great teachers and they were also — and still that church, St. Thomas Church, on Fifth Avenue, is ... their parishioners in the 1910s and 20s were the people who lived on Fifth Avenue. Well, who were they? They were the super rich. So the church had plenty of money, and a beautiful building.

And that’s why my dad encouraged me to go, because he said, “The worst thing that can happen to you would be just study every square inch of that building while you’re there.”

So I did.

Debra Bishop: Were you homesick at all?

Roger Black: Oh yeah. Sure. In fact, there were two teachers — the headmaster, Robert Porter, and Gordon Clem, Mr. Clem, who later became headmaster — one evening about week three said, “Maybe you should stop by Mr. Porter’s apartment after dinner.” And I did. And they were both sitting there.

And what I remember most about that encounter was that these men were sitting on either end of the sofa in two different chairs. And I was in the middle of the sofa and they were talking so quietly compared to my family that I could not hear either one of them. I had to ask them to speak up. And they said, “We’re concerned because you’ve been so upset.” And I was probably as far away as any kid there. A lot of the boys there in my class were local. We had people whose parents were in London. And they took me through it. They got me to ... it was like therapy. They took me through why I was homesick. And it was all empathy. It was all, “We understand. We were there once too. We get it. This is what we did," rather than feeling sorry for me. And it carried me.

I was fine after that.

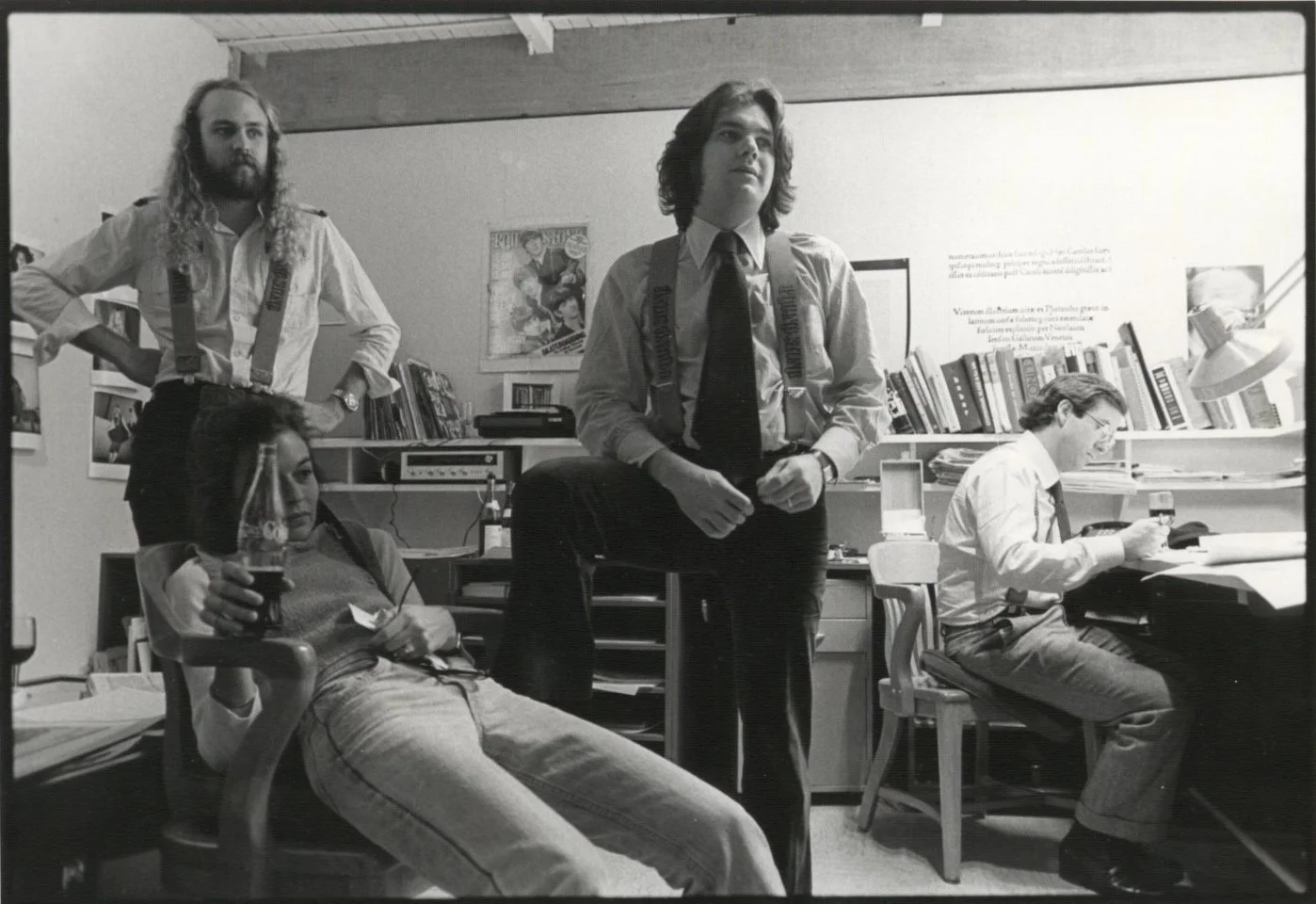

Black, far right, with Jann Wenner, center, in the Rolling Stone offices.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, your posh education was just getting started. You went from St. Thomas to the prestigious Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts, and then on to the equally prestigious University of Chicago. Princeton Review says, “Students at UChicago are both incredibly diverse and also consistently intellectual and quirky.” Do you think of yourself as intellectual and quirky?

Roger Black: Maybe more quirky. I must say that, well, after Deerfield, going to Chicago was stunning. They were all so much smarter than the average Deerfield kid. And they were all smart in different ways too. So that was very interesting. I mean some of them were math geniuses. I mean, some people — there were freshmen who knew more about astrophysics than I would ever learn. And it was a little hard to keep up with. There was enormous expectation of the students, spending essentially most of your life in the library doing research. And I wasn’t very good at that.

And in addition to which I started doing publications at Deerfield, I pretty much moved away from schoolwork to doing extracurriculars and learned about design that summer before college. I had a summer intern job, which was called an “apprenticeship,” and that shows you how old I am!

That cued me up in this ... I tried out for the Maroon, the student newspaper, and became managing editor sophomore year and the editor junior year. And my junior year at Chicago was 1968, which was an extremely good year to be a student editor …

Patrick Mitchell: … In 1968 Chicago!

Roger Black: In Chicago, yeah. In addition to which we had our own ... in addition to the democratic convention, and Mayor Daley, and all of that, we had great race riots, we had a sit-in and pretty much shut down the university. It was pretty crazy.

Patrick Mitchell: What was your major?

Roger Black: Political science. But I never graduated. I left to start a magazine, which I never regretted.

Patrick Mitchell: Wow. Do you think if you had finished that major you might have chosen a different career, or were you definitely headed …

Roger Black: No, I was doing that in order to become what I thought I wanted to be when I started and selected my major was a political writer, correspondent journalist.

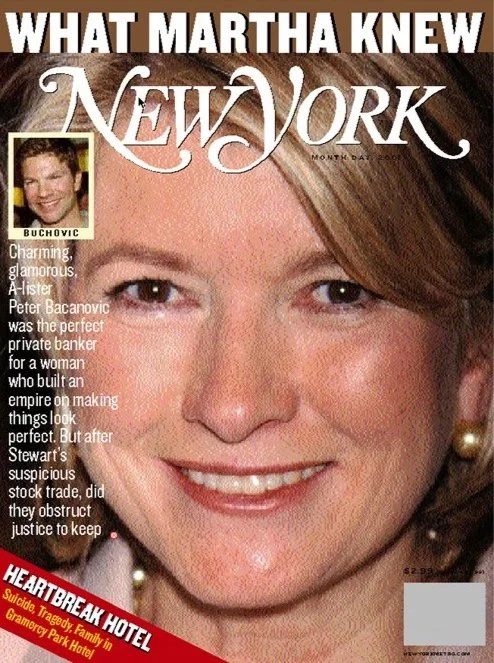

A 2001 Roger Black cover of New York Magazine

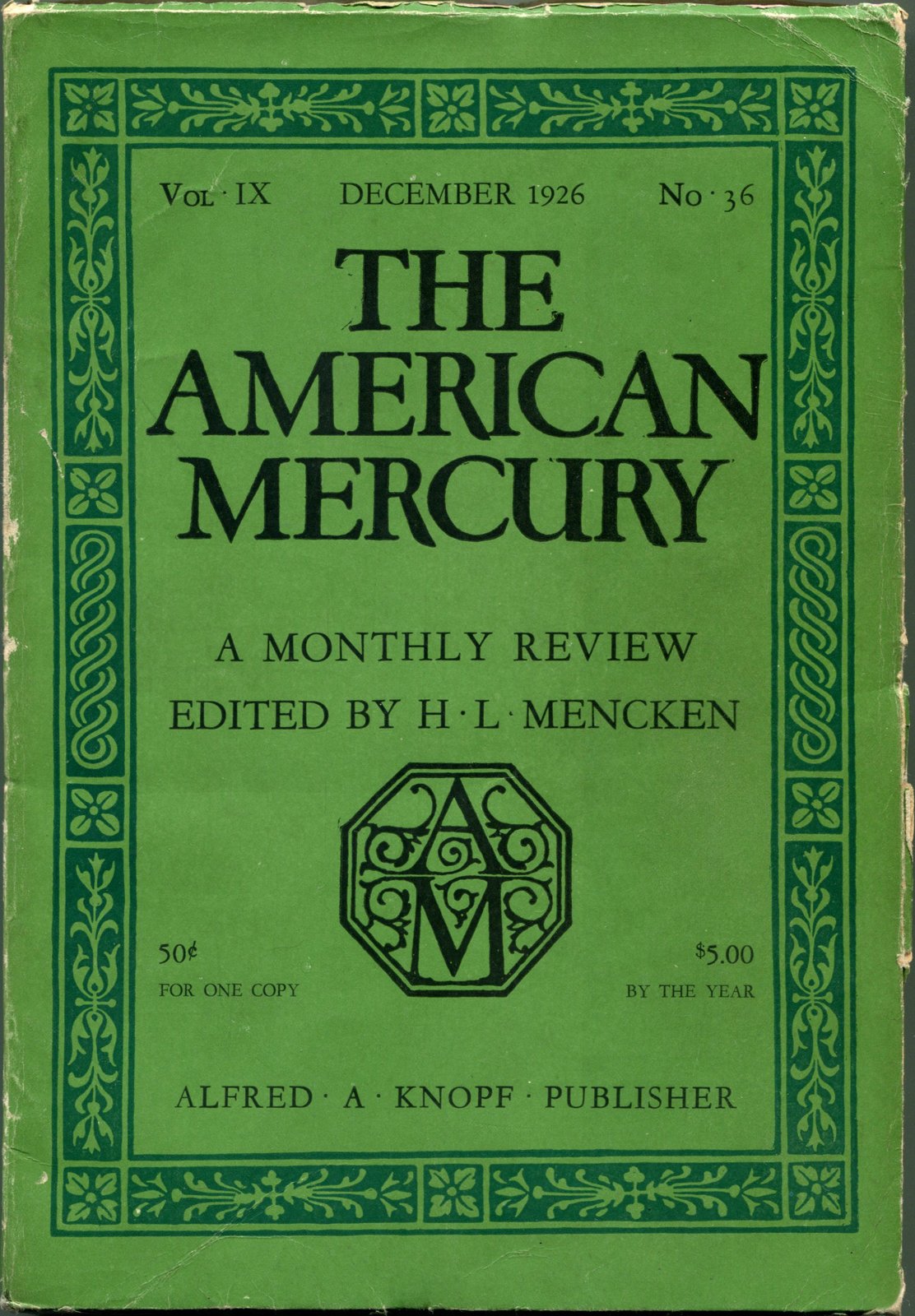

Debra Bishop: Your dad was a noted architect in Midland, Texas. And your mother, Eleanor, once worked at The New York Times and at H.L. Mencken’s The American Mercury, a very influential magazine from the twenties and thirties. What did they want you to be when you grew up?

Roger Black: They actually said that’s up to me. My dad said “you should not be an architect.” He explained on any number of occasions how horrible it was to be an architect. And if I had just done search-and-replace and said “art director” instead of “architect,” I never would’ve become an art director, because it’s the same thing.

It’s completely unresponsive clients, very difficult contractors and people you hire, very hard to staff, and almost no appreciation, and almost as soon as you're done, they tear it down.

Of course, at that time when I was listening to him, I didn’t think I was going to be a graphic designer. I thought I would be a writer. So I was saying that everyone thinks that they’re a frustrated artist, I’m a frustrated writer, and that may explain why I’m more interested in typography than anything.

Patrick Mitchell: I saw a quote that he once said to you, “You work a short time on pieces of paper that will be duplicated by the thousands and then thrown away.” When I read that, I couldn’t believe I’d wasted my entire career! Did they approve of your career choice?

Roger Black: No.

When I got to be the art director of Rolling Stone, my dad thought that was okay. My mother didn’t live for me to be the art director of The New York Times. But my dad said, “I wish she had lived for that. It would’ve redeemed you in her view.” So there was something very nice about going back to New York and working in the same building as she worked, the 43rd Street building.

Debra Bishop: A few years ago, you made several posts on Facebook about someone named “Pinky.” The photos and memories you shared were very raw and moving. Can you talk about her?

Roger Black: Well, Pinky was my first spouse — I guess that’s how you have to say it these days. We met in LA. My first job as a publication art director was in LA for L.A., a weekly tabloid, which didn’t last very long, but set me up as a designer. I learned a lot, met a lot of people. And I had, in 1973, started a studio with Tom Engels and a fellow named Jim McKinsey called Type City. And I also was working under my own name doing publication design, but Type City was going to do typography and make logos.

We had something called “Instant Logo,” where, for $100, you could have as many logos as you wanted. And it almost killed us when the Grammys — not the Grammys. What was it? — Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass. A&M records decided they were going to change their name. He was going to call it Herb Alpert & The TJB [laughs].

So the art director of A&M called up and said, “You know that Instant Logos? Can you send 20 over by the morning?” And I think we said, “Can we do 10? We can’t do 20, we’re too busy.”

I think maybe they asked for 50, and we settled on 20.

And Tom and I sat up all night doing logos and it was really fun and it was the most money we ever made in that company, I have to say.

Anyway, so I was in LA, wandering around, and a young kid named Allen Ehrenberg came in to work as an assistant. And his girlfriend lived in this beautiful apartment building in Brentwood, the fancy part of Santa Monica. And Allen came from a very prosperous family. And his mother had divorced and remarried the guy who owned the Philadelphia Eagles, and she had a house in the Malibu Colony, and Allen would invite people out there sometimes on the weekend.

So we all went out and sat out on the beach, had a great time. And so there was one very pretty young woman whose name is Clementine van Deusen, and also from a prosperous old family. They used to live in the colony too.

And we were lined up and it was Sunday and we all had newspapers, and I said, “Does anybody have a rolled reefer?” And they did, of course, it was 1974. Everyone had rolled reefers in those days.

Clementine van Deusen, aka, “Pinky,” was Black’s first wife.

And then I realized I didn’t have a match. I said, “Does anybody have a match?” Then I kept saying that, and there’s a nice breeze, it’s hard to hear, people weren’t paying much attention. And finally, Pinky got aggravated that I kept wanting a match and nobody was helping, so she said, “I'll go get you a match.”

And so she went into the house and came back with a match, and as she’s stepping down, she hit a splinter on the stairs and screamed. Actually, it was a shriek, a really blood chilling shriek.

And I ran over it and said, “Now I felt guilty,” because she had hurt herself trying to get me matches so I could smoke pot. And we started talking, and that evening everyone was tired of the house. We thought we’d go into Malibu. The only restaurant we could think of was Alice’s Restaurant on the pier. And everyone said, “We hate it. You have to remember that we hate it and it’s expensive and we don’t have any money, so let’s just play it cool.”

And so we went in — and some of these were rich kids and some of them were people like me, just trying to make a living — and they hated it. And I had spent my last $7 getting a shrimp cocktail and a margarita — that was my dinner. And they decided they were going to leave. Just get the check and get the hell out of there, and go to the Corral. Or, no, The Stampede, which is some horrible country-and-western bar in west LA.

And Pinky and I had said, “No, we’ll just go back to the house. Don’t worry about us.” And so we did, and we were walking back along Pacific Coast Highway, it was about a mile and Pinky was limping because she had hurt her foot so I was trying to help her. And we complained about the spoiled rich kids. And that was the bonding thing. There’s nothing more bonding than both hating the same kind of thing.

So a year later we got married.

Debra Bishop: The famous New York Times street fashion photographer, Bill Cunningham looked at an old contact sheet of pictures of her and said, “Ah, Pinky. Pinky was the ’70s.” You, as an art director of the hottest magazine on the planet, and Pinky, as a fashion icon, must have been quite the power couple. Can you talk about those years in California?

Roger Black: In California, that’s not when we became the power couple. She had become really interested in fashion, but it was not until New York and I got a little more money.

We moved to Gramercy Park, suddenly we were the toast of the town to be working at Rolling Stone. And then she met, in London, a designer, Rachel Auburn, who now is pretty well known as a DJ, but was quite a big fashion designer in the “new romantic” era.

And she would get foot lockers from London and there were wool garments beautifully made and you wondered what animal, which species was this thing made for? It looked like it had extra arms on it and stuff that she would wrap around her body.

Anyways, Bill Cunningham loved all that. And we were at 59th and 5th, and Bill used to hang out at 57th and 5th at lunchtime because that’s where all the ladies who lunch paraded by, Jackie Onassis and everybody, there was Lutèce, and Côte Basque and that’s where they went.

And so Pinky would just be walking down 5th Avenue, maybe to go to Rolling Stone, and he would take her picture. So he had hundreds of pictures of her just on the contact sheets. Every now and then she would get in the Times. So it was definitely quite a scene.

I’m reading Jann Wenner’s book, which is coming out this fall. I got an advanced copy from him. It’s pretty amazing. He’s very nice to me, but he describes how crazy we all were, including himself. Now, we were running around New York at night in limos going to Danceteria and Studio 54.

Debra Bishop: You once said if she hadn’t left you, you’d still be together today.

Roger Black: Yeah. I don’t leave people. And we were very much in love. She had her own ideas about what she wanted and she decided it was not to stay with me. So she moved to Tortola for a while, and then ended up back in California.

Just a couple of kids in love: Scenes from Black’s earlier life with Pinky.

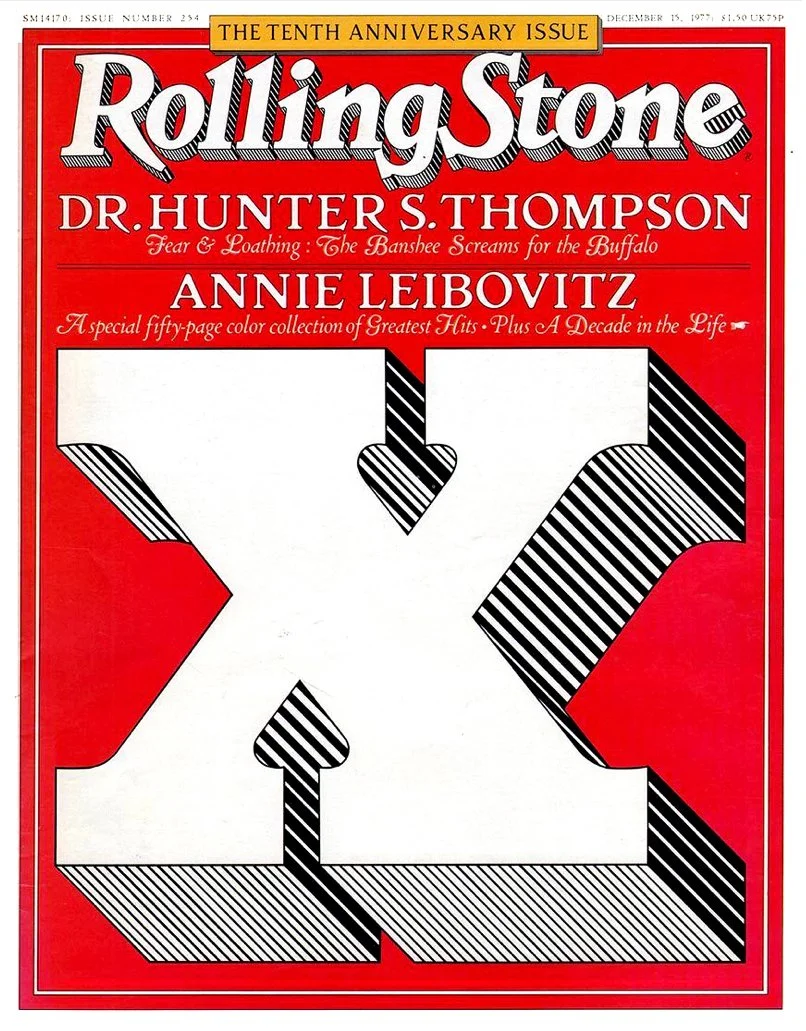

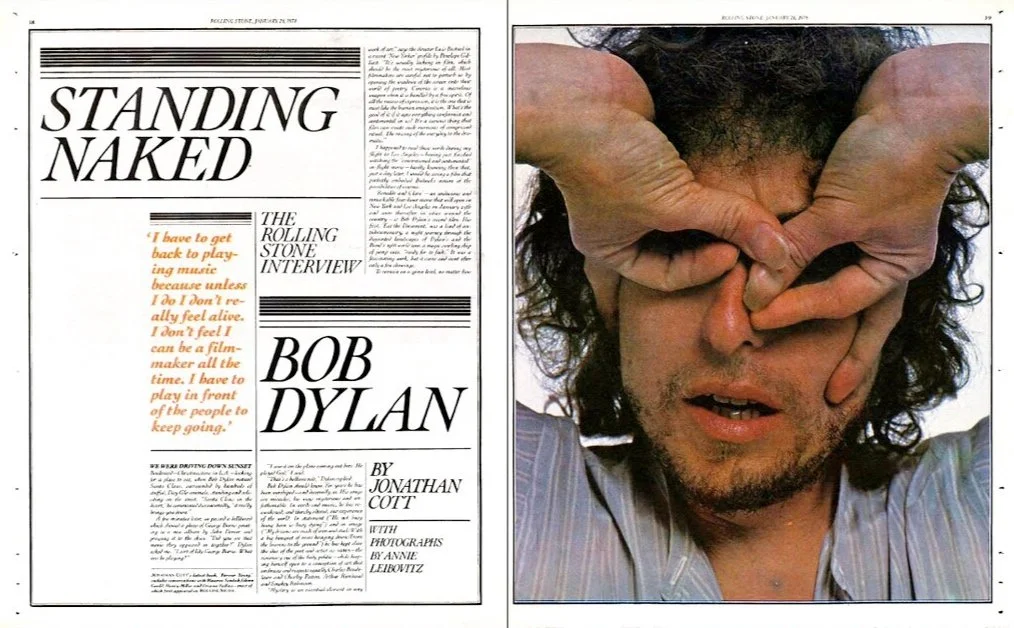

Patrick Mitchell: Speaking of Jann Wenner, you were at Rolling Stone in its heyday with Jann, Hunter Thompson, Annie Leibovitz, Cameron Crowe, Lester Bangs, Tom Wolfe. You were all around 25 at the same time and trying to run a business. How did a bunch of kids get a magazine out on a regular schedule — a biweekly schedule — at that?

Roger Black: Well, there are a lot of us, but Jann had gotten successful very fast and hired everyone he could think of, everyone he could find. He was a very good judge. He also had the wonderful human resource trick of getting rid of anybody that didn't work out very quick, which big companies have a hard time doing. So there was very little risk in hiring anybody because he’d fire them.

And so everybody was on trial all the time in a way. He was very indulgent to the writers, which is maybe why the magazine read so well. And he was a very good judge of talent, so he’d get all these kids in, but everyone thinks it’s all kids. It wasn’t all kids. Tom Wolfe was doing some of his best work for Rolling Stone and there were others. Jan Morris came in when I was there and did these amazing travel pieces that, if we were lucky, we would assign a photographer.

I remember she went to Panama and I got Nancy Moran to go down there, and Nancy says, “What do you need?” And I said, “I want to see, in one picture, if you can possibly do how the Panama canal works.” People are vague on that.

And sure enough, she got on top of a mountain and took this giant picture, which we ran as a double truck, that showed it exactly. There’s the lake where these freighters are lined up and then one ship is high, one ship is low. It’s like, “Thank you.” It’s so wonderful. She was — is — she’s still around, and she’s a great photojournalist.

But that was the other thing, pretty much anybody would work for us. Just call them up and they would say “okay.” And we had enough money so we could pay reasonably. It was not the great era when covers got paid. In the ’40s, a cover would be paid $10,000 to the artist, but we would pay $1500 or so in the ’70s.

So everybody — Milton Glaser, and virtually every known illustrator at that time, Danny Maffia, did some wonderful things for us. Jim McMullen, Phil Hayes, everybody. And then of course the photographers Jann hired. Hiro, who just died in the last year — one of the great photographers of the 20th century in my view — to do stuff he hadn’t really done much of, which was portraits. But he originally was hired to do the space shuttles. It’s bizarre. He did the famous picture of the spacesuits on a cloths rack, like it was 7th Avenue.

It took me 20 years to realize that was a setup, because unlike photojournalist — because he was not really a photojournalist — he did an advanced trip to the whole shuttle program: Cape Kennedy, and Houston, and California, and Huntsville, I guess.

I remember we got the bill for that. It was two first class tickets and fancy cars at four-star, five-star hotels. And I gave it to Jann — it’s thousands of dollars — and he said, “Yeah, I’ll pay it.” That’s not [inaudible 00:27:31]. So, that was the thing, we were doing very interesting things and people would work for us so we got everybody. It was fun.

Patrick Mitchell: In your blog, you tell a very funny story about a “stop the presses” moment that I wish was at Rolling Stone, but I think it was at L.A. Can you share that?

Roger Black: Oh, that was Bill Cardoso, the famous Bill Cardoso line. Cardoso was the inventor of the phrase “Gonzo Journalism.” And he’s the guy who introduced me to Hunter Thompson in 1972 at his apartment in West Hollywood. Anyway, he had done The Boston Globe Magazine and then had retired to the Canary Islands and ran a jazz bar for a number of years. He got bored with that and came back and got this job with Karl Fleming and Bob Sherrill — the good Bob Sherrill — at L.A.

Anyway, it was 1972. And at one moment he comes running back to the art department, yelling, “Stop the press!”

And we all look up, like, “What?”

And he says, “I lost the hash pipe!”

So we had to help with that.

“Stop the presses! I lost the hash pipe!”

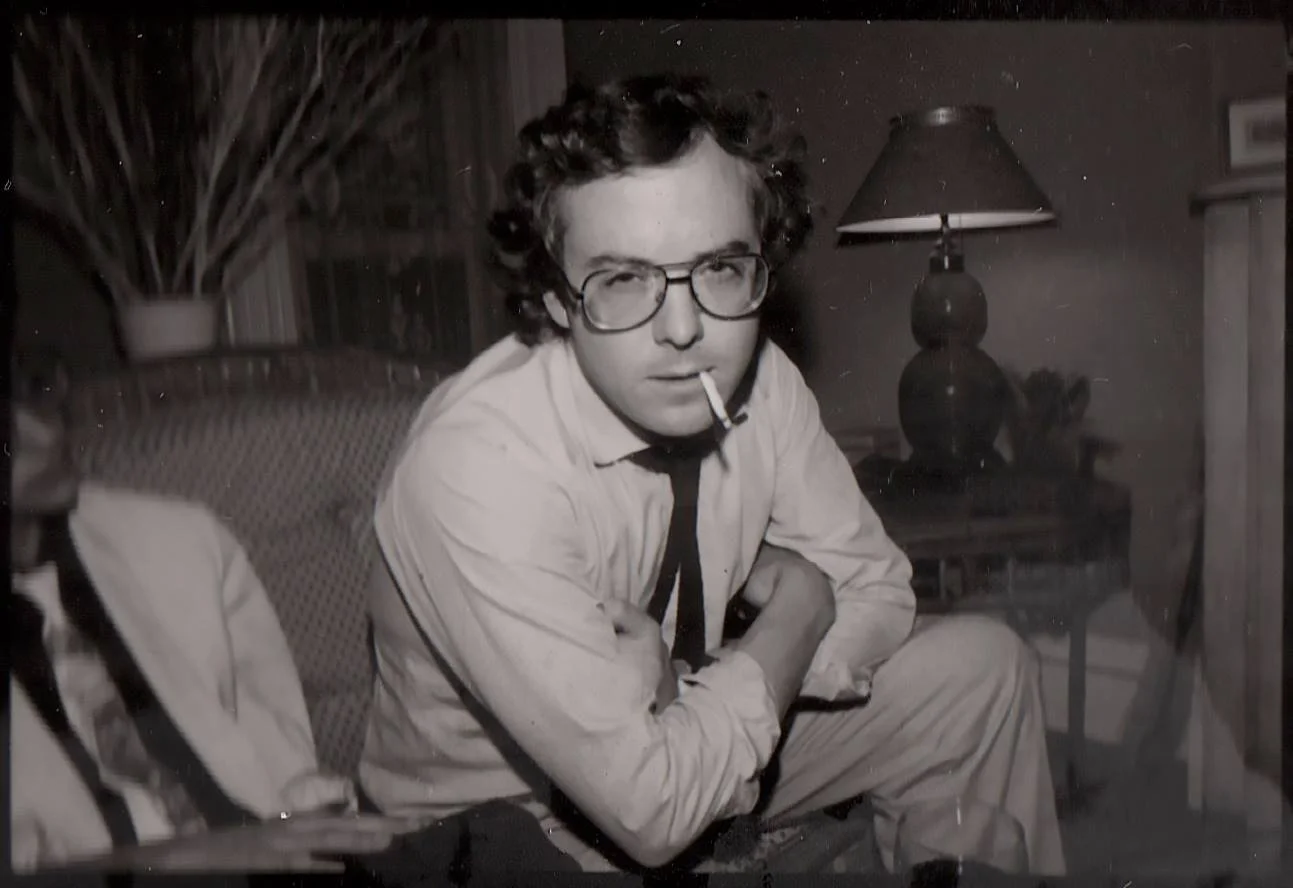

“Does anybody have a rolled reefer?” Black in his Rolling Stone days.

Patrick Mitchell: It's a funny story, but it says a lot about those times, and even at a business like a magazine, things and people get out of hand, including you. You told me about an instance in New York, shortly after moving there, when you experienced an intervention and were given an ultimatum. Can you talk about that?

Roger Black: Yeah. The New York Times confronted me because I was really drinking much more than I was doing drugs at that point. Basically, I’m one of these people who can attest that marijuana, if it becomes a daily habit, leads to other addictions. And it did in my case, with cocaine. And then that led to alcohol because cocaine and alcohol go very nicely together.

Cocaine tunes you up if you’ve drunk too much and alcohol calms you down if you’ve taken too much cocaine.

This is what happened to Hunter Thompson. That spiral becomes very difficult to handle because you’re addicted to both. And at one point it became clear to Lou Silverstein, my boss at The New York Times, that I was not going to make it if they didn't do something.

So they had an employee assistance program (EAP), which, we’re talking about 1982. So you got to admire them firstly for hiring me knowing that I had a problem. But then you have to admire them for putting up with me and trying to help.

So I started going to this EAP guy — who became essentially my first sponsor — and with Pinky and other friends, they did an intervention and said, basically, the choice was you’re not following the program, you’re not... “You could either go to rehab or you could leave the premises now. Don’t pack your bags, just get out of here.”

And didn’t take me very long to say, “Okay, you’re right. I’ll go to rehab,” in, I would say, 30 seconds. I had passed the denial period at that point and had realized that I had a problem and I could die.

I think that the way that people get over addiction is to realize that you are going to die if you don’t do something. And that’s also the message. It’s true, you will. And I know, I’m going to say, dozens of people who didn’t take that opportunity to stop. And the only thing I would say that we really need to do is do more education about that. People don’t understand that drugs do lead to death and or that there’s help. And if they did, more people would get into the program.

This is going to be my 40-year mark, as they say, “God willing …"

Patrick Mitchell: What was that time like when you came back from rehab?

Roger Black: I initially thought that I would never be able to think again, because I think a lot of people who do a lot of drugs and alcohol think that’s helping them, and I quickly realized it was actually not helping.

Patrick Mitchell: Helping you in terms of … ?

Roger Black: Creativity. It actually was a crutch. All addiction is like that. You’re addicted to the substance, there isn’t a reason for it. If you did a log of all the times you did drugs or alcohol or smoked cigarettes or whatever it is you’re addicted to, there would not be a pattern. It’s like you do it when you’re happy, you do it when you’re sad, you do it when you’re tired, you do it when you wake up. It’s because you’re addicted, it isn’t because it’s an antidote to anything. You just think that, that's an excuse.

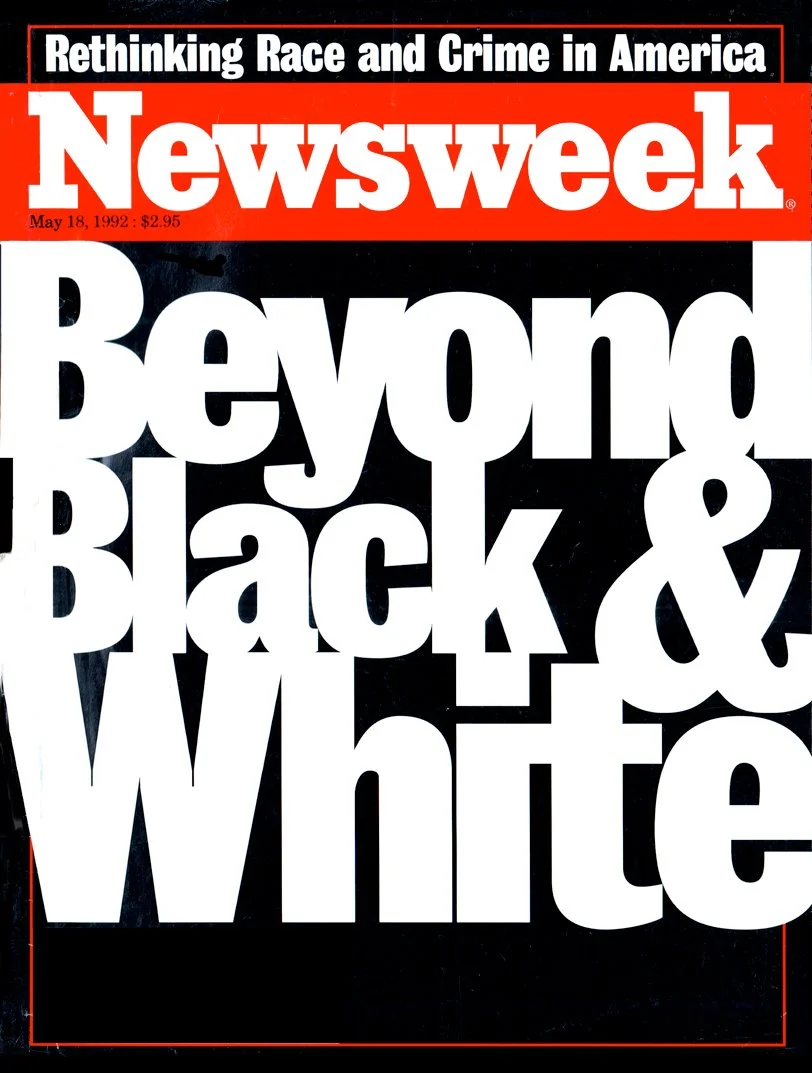

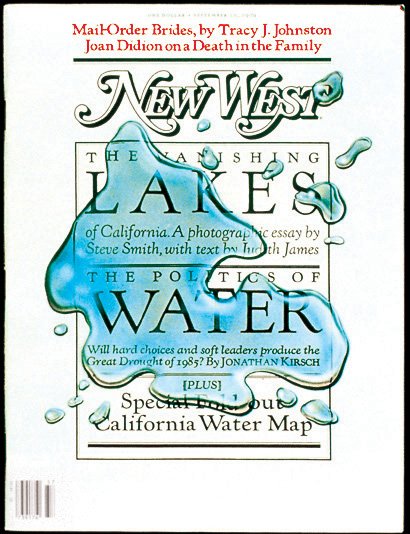

Debra Bishop: After Rolling Stone, you began a grand tour of the magazine business that included stops at New York, New West, The New York Times and the Times Magazine, Newsweek, Smart and Esquire. All in the span of about 10 to 12 years. What was the driver behind so many stops?

Roger Black: Well, I was doing redesign basically, but the thing is that I quit Rolling Stone without really knowing what I was going to do next, but very quickly Joe Armstrong, who had also quit Rolling Stone as publisher had gone to work for Rupert Murdoch who had bought New York and New West called me up and said, “Do you want to do New West?” And I said, “No.” And he said, "Yeah, but you’re probably going to do New York too, but we have an art director there and it hasn't been worked out yet.” And I said, “All right, but you have to pay me a lot more than I’m making now,” because that’s one of the reasons I quit Rolling Stone.

Jann puts in his book that the reason I quit Rolling Stone is exactly the reason. And I asked him, “How did you get that story right?” I mean, people’s memories are usually not that good. He said, “Don't you remember? I interviewed you!”

But it was really nice of him to tell that story, because it’s sort of on himself. Because I said I would stay at Rolling Stone if he paid me a little more money or if he came back and acted as editor and stopped all this nonsense of being a celebrity and rich person, but he declined.

So I left, but then I didn’t know what I was going to do, but Joe called, I ended up moving to LA, which I kind of liked. And then he immediately said, “Could you come back for a little bit and meet Rupert and talk about the New York Post?”

So, like, month two, I flew back and met Rupert Murdoch and did a redesign of the New York Post in my spare time, which was really fun. And Rupert wanted to do something. It was sort of like Tina Brown, it was a high/low thing.

They’re going to take the New York Post, which still had famous names and some great reporters, but they wanted tabloid sales. So he bolted gossip on there. That’s essentially Tatler, Vanity Fair.

And so I did this very juicy tabloid design and had quite a bit of fun with Rupert, and got to know him and Anna, who is his second wife, who is those people from News Corp — the Murdochs — are her children. And he says, “You know, it’s really fun, Roger, but we decided I’d have a lot more respect in town if we took the high/low approach, but it’s going to be so much easier just to do low.”

Debra Bishop: During that span Roger, what was your favorite job?

Roger Black: The New York Times. I mean, what happened was during that period, the Times hired me to do the magazine, and then, after they made me clean up my act, they pretty much said they were grooming me to be the new art director because Lou Silverstein — I didn’t understand there was some mandatory retirement age and that Lou was reaching it — and they were going to have to find somebody else and it turned out he wanted me to do it.

And so he made me the senior art director, where I padded around following him through the newsroom and doing all this other stuff. And then he did retire and they made me the art director, but it was very frustrating. And then I realized that Abe Rosenthal, who was my mentor/boss, he was going to have to retire. And they were going to bring in more typical non-visual person to be the editor.

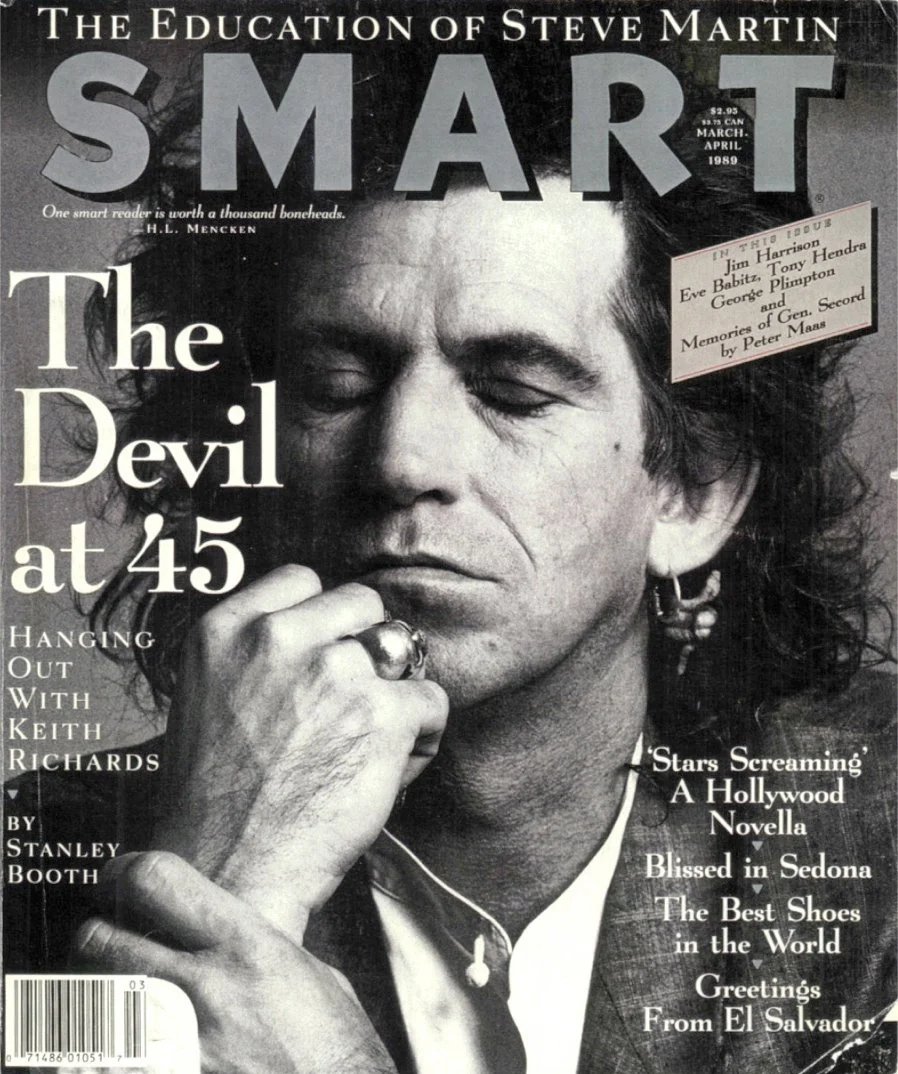

Debra Bishop: Who was the best editorial partner that you’ve ever worked with?

Roger Black: Well Jann is clearly, probably at the top. Terry McDonell, we worked in a number of places, including Smart. Yeah, that would be the short list. But I can’t say that I’ve really met, I mean, all the successful magazines had good editors. If they’re really ugly magazines that I’ve done, they’re bad editors. I’d blame that.

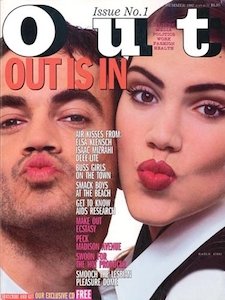

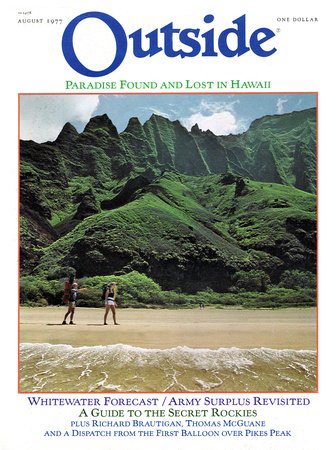

Patrick Mitchell: Can you name, as a reader and not including former clients, what you would say are the five best executed magazines ever?

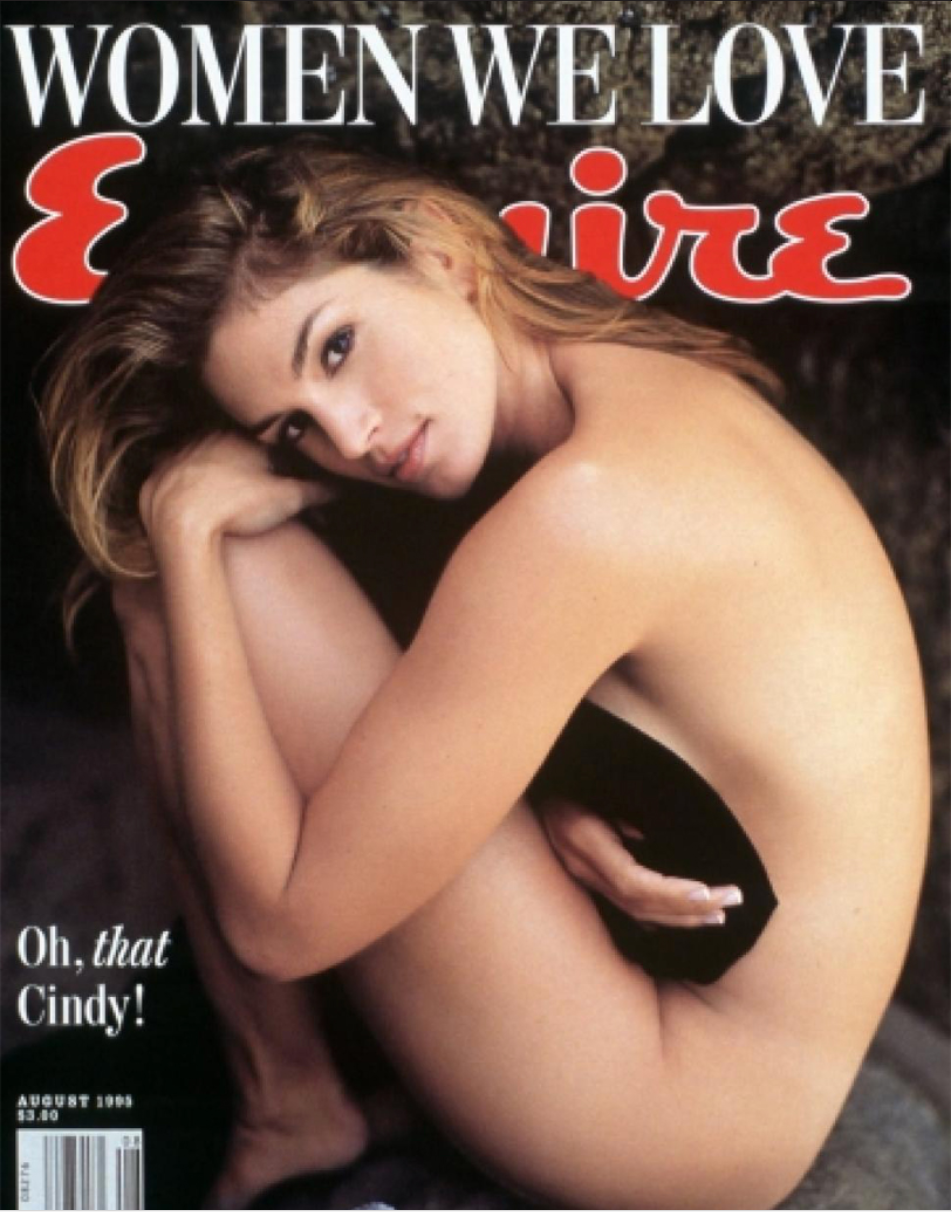

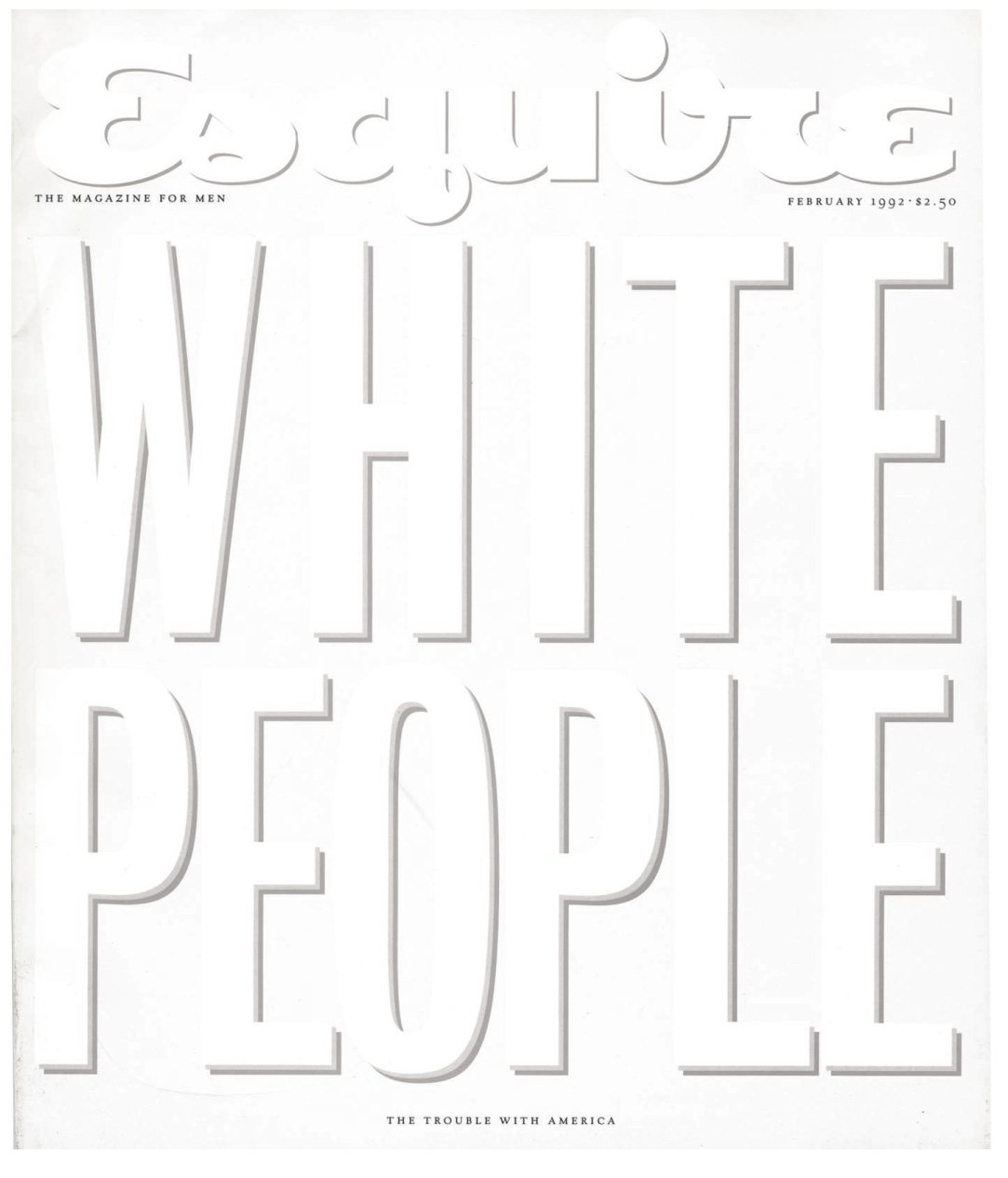

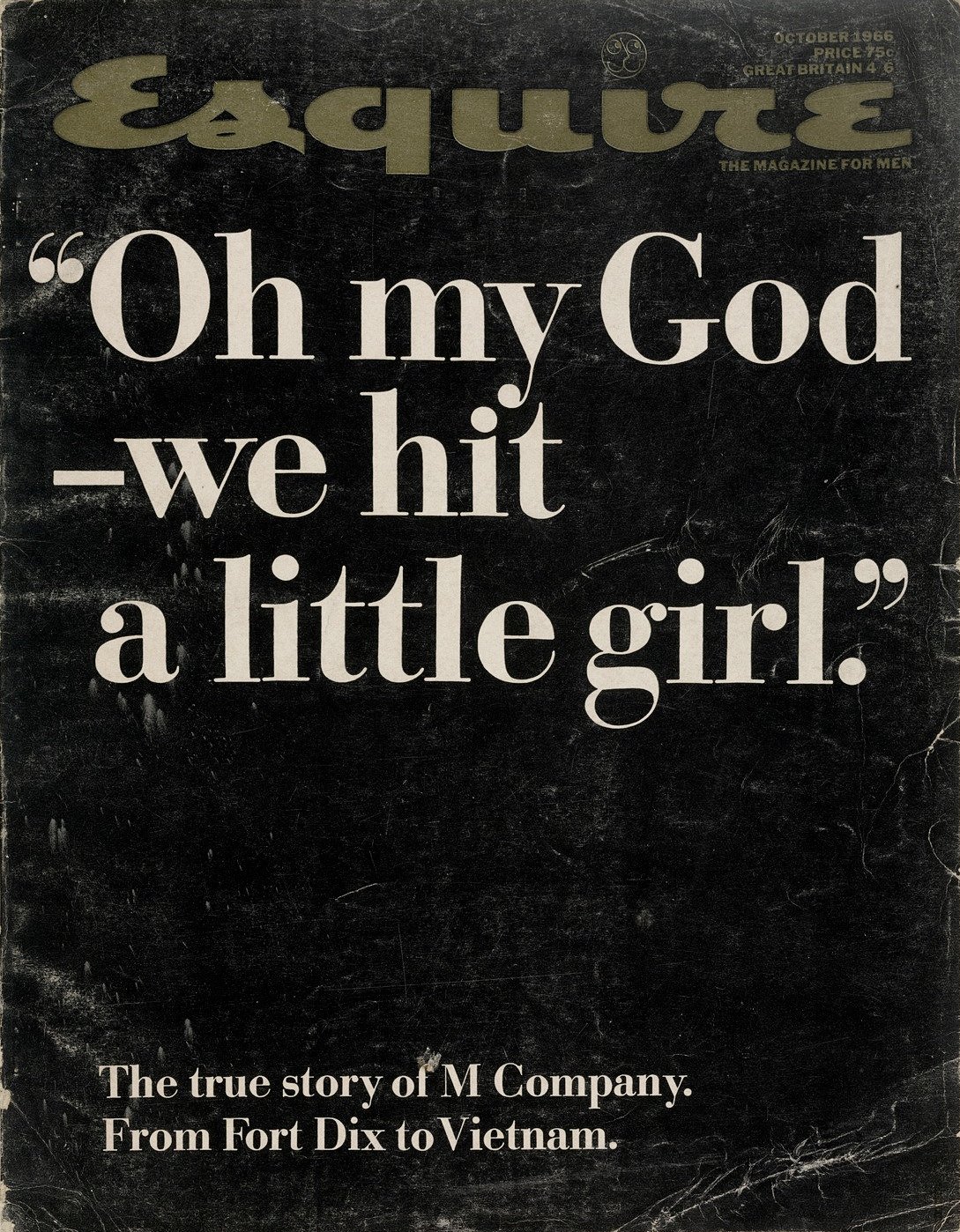

Roger Black: Well, I’m glad you gave me a hint that you’re going to ask that question because it probably changes every time you ask, but I think top of my list has to be Esquire under Sam Antupit. Sam Antupit is the one who made me understand that there was a job for art directors, magazine art directors. Because I worked with him on Print Project Amerika in 1970. And George Lois did the Esquire covers. Everyone thinks it’s George Lois’ era. He never did the inside pages, but he was a genius on doing the covers. Harold Hayes was the editor.

And then from my childhood — only vaguely aware of it as a child — was Cipe Pineles at Charm.

Charm, I think, is one of the great magazines of all time. It was stupidly named because it was a magazine for working women in the early 1950s and still looks fabulous. It was beautifully art directed. The photography was flabbergasting. Of course, the idea that a woman would wear something like that to work today is, you know, they were gorgeous at the factory.

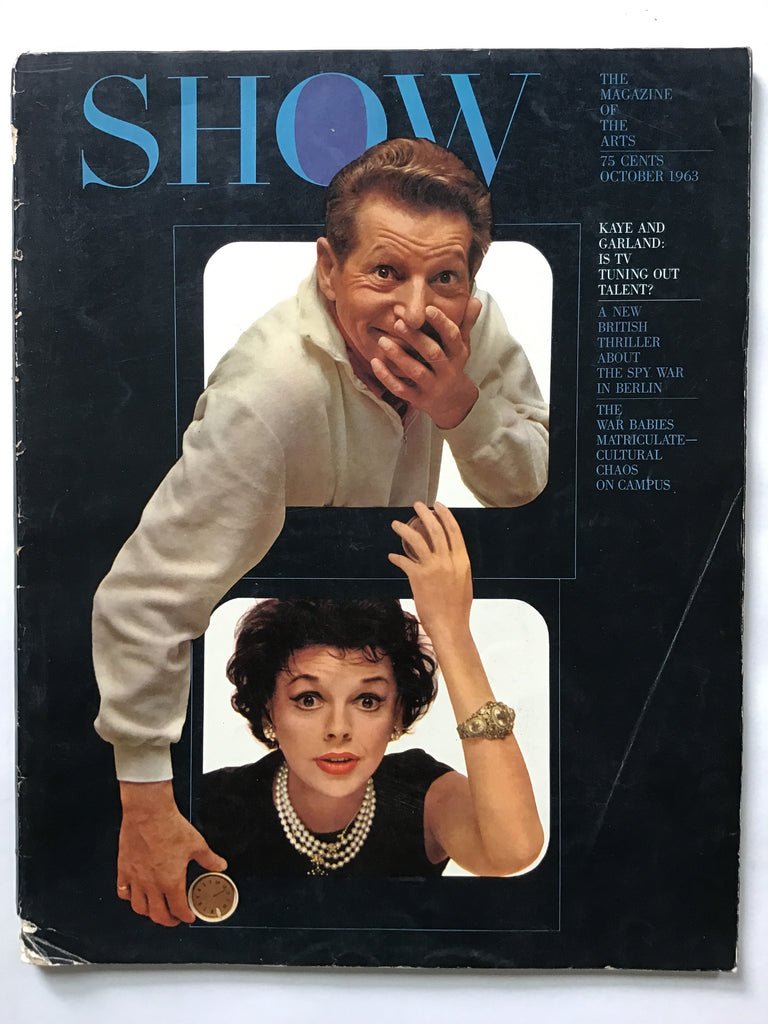

Then I would say probably Show. Henry Wolf’s Show, because I subscribed. I was a subscriber back at St. Thomas Choir School and also a patron to the Gallery of Modern Art, which was Edward Durell Stone’s building for Huntington Harvard’s own show. But I loved that magazine. It was really surprising. It was amazingly lavish. I don’t know how I saved enough money to subscribe.

And then I would probably say The American Mercury itself, which had no art, but great stories and great type and very easy to read and beautifully edited.

It had the classic look with the front of the book. Mencken, H.L. Mencken, was one of the genius editors of all time. And he created, I mean it was 1924, a year before The New Yorker ever started. The New Yorker was essentially just was cribbing The American Mercury when they started. And their big donation to mankind was the cartoons.

But The Mercury didn’t have squibs (coverlines). The art director was Elmer Adler. Adler invented this whole game before the people who taught us were even born.

And The American Mercury was Garamond — ATF Garamond that Fred Goudy designed. People say it’s not really Garamond okay, fine. It’s a very, very good letter press text face, but stylish. So it’s perfect for this magazine and it was set up perfectly with the right widths and all that. And it was printed by the Haddon Craftsmen in Canada. Beautifully printed.

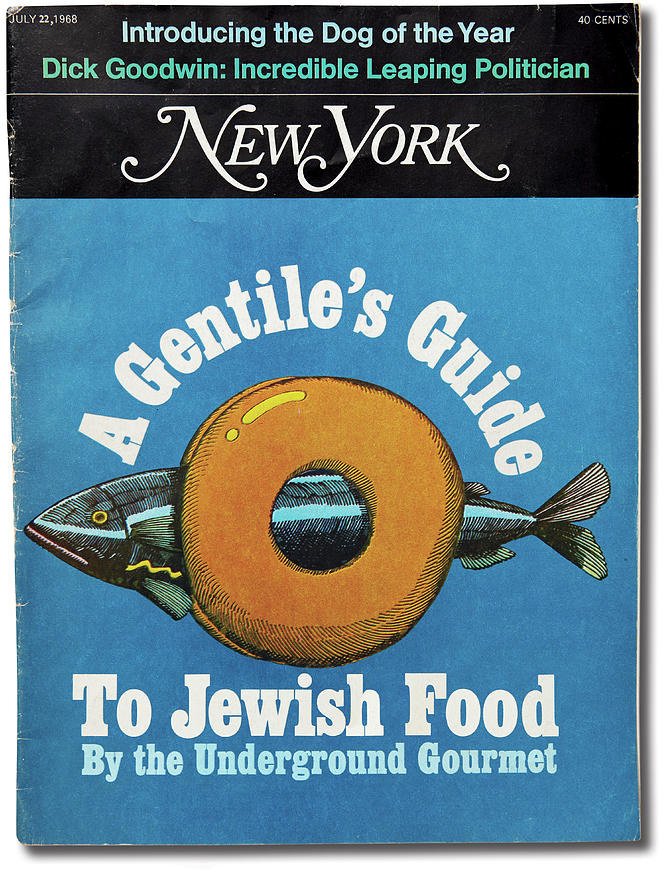

Number five would be New York under Walter Bernard. And that was, typographically, not … I think that the kind of evocation that they’ve done now at New York magazine — with the Egyptian Bold Condensed as their kind of “show face” — is much more typographically interesting than it was under Walter. Of course you have to remember how bad the printing was in those days.

But his art direction, his sense of pacing and all that, in a weekly magazine is fantastic. And it created the business.

Suddenly everybody wanted to, I think Rolling Stone and New York — which came out the same year, 1967 — created a demand for art directors. And that was how I got started because I didn’t have any experience. I was a kid, but they didn’t have any experience either, so they hired me. It was great.

Patrick Mitchell: There weren’t really our directors before that.

Roger Black: Yeah. Not like we had in the 20th century, no.

Roger Black’s 5 Best-Executed Magazines of All Time

Debra Bishop: Was Roger Black Design just the next logical step on your career path?

Roger Black: Yeah, because once I realized what I was doing was redesigns and formats, I wasn’t loving the art director part. I enjoyed it. But as soon as possible, I got other better people to do the work like great photo editors and associate art directors who were really art directors who had that Rolodex we had at Rolling Stone, there were four associate art directors in New York working with me and then two or three assistant art directors.

And then we had a paced up team that include people like Robert Raines, who became art director of Book of the Month Club and AOL, and April Silver became art director of Esquire. She was a paste-up person at Rolling Stone. And yeah, we had an amazing backfield plus the whole photo desk with Carol Malarkey as photo editor, Susan Vermazen as associate.

Patrick Mitchell: Actually, before we get into Roger Black, Inc., I wanted to share this quote I read and I’m not sure the source, but it says, “Roger draws a monthly consulting retainer as the design director at Esquire and as the grand design consultant to the Hearst Company” — that’s when I met you — “The idea is that Roger will become a kind of Alexander Liberman at Hearst, except that Roger will be free to work from his Hearst offices on his many other non-Hearst projects and assignments.” Was that the beginning of Roger Black Inc?

Roger Black: No. Actually Roger Black Inc. was incorporated in 1982, when I quit New York. I freelanced for a year before The New York Times hired me and I had a really good time. We did some funky publication work, but I also did Martha Stewart’s first book Entertaining. And my favorite magazine work was for Don Welsh, another ex-Rolling Stone person who had Welsh Publishing, which did children’s franchise magazines. And the one I did was Muppet, my favorite.

Muppet Magazine was, at that time they had the Muppet Mansion and I got to work directly with Muppet people. And the whole idea was to make a magazine that looked like The Muppets were putting it out. Like their TV show. And so Miss Piggy had the advice column, for example — my favorite. And it was all real Muppet art and then celebrities, like the TV show. Robin Williams was the first cover. That was fun.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, was this idea of becoming the Alexander Liberman of Hearst something that was discussed there?

Roger Black: Well, they never used that phrase because they hated everything to do with Condé Nast. So that wouldn’t be their admitted model. But they wanted design at a higher level than they had. And people forget when Randolph Hearst bought Cosmopolitan — he liked magazines. The only magazine he ever started himself, though, was Motor, “a magazine for chauffeurs and mechanics.” Because he thought they needed some information [laughs].

But Claeys Bahrenburg, another ex-Rolling Stone ad salesperson, had become the head of Hearst Magazines. And people forget that there were quite a few good art directors and visual-minded editors. I think of John Mack Carter, who had become head of magazine development. And he was still editor of Good Housekeeping and was the old Hearst Building, which is now just the base for the new Hearst Building. And on the top floor was the Good Housekeeping Institute with John Mack Carter and his test kitchens and quite an elaborate dining room.

So, I mean, there were a lot of people at Hearst who cared about these thing. Helen Gurley Brown, of course. But some of the magazines were getting a little long in the tooth in terms of design and they wanted to get more commercial. They wanted to compete more with Condé Nast, at that level.

So I came in to do Esquire, but the idea was that I would be kind of consulting art director for everything.

So I slowly redid, you know, I worked on Town & Country a little bit. Did House Beautiful, I mean, just consulted. And I remember Richard Deems [former chairman and president of Hearst Magazines], after the whole thing and we had waited and talked to the editor — he’d been there a long time — got the redesign approved and moved on. I said, “So Dick, what did you think?” And he says, “Well, as the old man [William Randolph Hearst] used to say, ‘You can light your cigar with a hundred dollar bill, but it’s still just a smoke.’”

So … squash. Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: How long did things last at Hearst?

Roger Black: It was maybe four years. So yeah, it was really all the way through the ’90s I had something to do. I got out of Esquire pretty quick. And that was because [Edward] Kosner showed up [laughs].

Kosner has become a very sweet guy in his old age. I hope that happens to me. But he was doing the same thing, trying to save it. Terry McDonell had been the editor and run it into the ground as a business. Although it was a really interesting magazine, really fun, and Rhonda Rubinstein had become the art director and was really doing all the work.

One of the proudest things in my career is that almost all my successors at magazines were womn. Mary Shanahan was my successor at Rolling Stone. Patricia Bradbury was my successor at Newsweek. Diana Laguardia was my successor at The New York Times Magazine. And it goes on.

And why was that? Well, because all these great art directors I would hire, and then I would get the hell out of the way. “I’m just slowing you down.”

Debra Bishop: I read an article where you said back in the mid ’90s, “Don’t have a lot of text. Nobody reads anything anymore. The only person you can count on to read every word of what you've written is your mother.” You were at the forefront of putting real editorial online. How do you think it’s going now?

Roger Black: Well, it’s a complete mix. It goes all the way from very, very high end … to nothing.

I don’t know where that quote came from, but my feeling has always been, you don’t want to give the impression of a lot of text because people would be turned off. If you take a look at The New York Times Magazine today, which wins all of the awards, they don’t make any concession to the reader.

There’s a lot of sometimes very exuberant and wonderful design work or artwork, typography. And then there’s the text just layered in. And then, just like what you had to do in the ’80s, the text jumps to the back. It’s like, really? Why is anyone doing jumps when there’s no ads? I don’t understand that.

But the end result is that you look at the raw text, you say, “My God, there’s a lot to read and it looks difficult. I’m not going to read that.” So the job is to entice them into it, to give them enough information so that if they don’t read it, they still enjoy the article. And that includes the writing, you have quotes or you have big, big chapter openings, good chapter titles. Great captions.

Patrick Mitchell: Can you explain Apple News to me? I mean, they’ve hired away some of the greatest talent in the magazine business, and yet you’d be hard-pressed to see any of that creativity in their editorial output.

Roger Black: Well, I only have one Apple [product] left, which is an iPad, because I find the Apple environment suffocating. And I guess that’s what happened to those guys. They got inside that giant dome, and there's not enough oxygen in there — despite all the plants, trees and things [laughs]. You think that they would be making oxygen at Apple, but it’s very interesting to compare Google’s version of that, which is called Discover, which is an adjunct of the Chrome browser.

It also appears in Android. You just kind of swipe to the left and it shows up and it refreshes.

Of course, like everything Google — and I think Apple News is the same way — it follows what you’re interested in so that it creates a little bubble. Google does a little more random, interesting stuff, which is my definition of something that’s good about newspapers, but Apple, I don’t read it enough so that they know my preferences very well, but I’m very frustrated when I hit a link in Apple and it goes to a subscription page … very often.

Patrick Mitchell: I’m thinking about their presentation of newsstand magazines, which all mirror each other, identically.

Roger Black: Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: You’ll see a magazine’s logo, but then every layout of every story of every magazine is exactly the same.

Roger Black: Yeah. You know, it reminds me of the ill-fated iPad experiment at Condé Nast where half of it was sort of PDF magazines, but the other half was their templated magazines. And one of the worst things that’s happened in this modern era is the kind of standardization of formats in groups. For example, Hearst Magazine took my design of the Houston Chronicle, a multiple-design effort at the San Francisco Chronicle that included Jim Parkinson's amazing fonts, plus whoever did the San Antonio Express-News, and just gutted the local designs, and replaced them all with a kind of well-intended design that is just generic.

And then Gannett, or whatever it’s called now, they have “hubs,” so that one whole section of their newspapers, which don’t necessarily relate to each other, all look alike. And then you move into the web, and you get all these templates from the various platforms that — WordPress or whatever — and they all start looking alike.

I mean, the Russians figured this out when they were gaming the last election, because they could put a nice WordPress newspaper template up and make a newspaper and people would think it was real. Because it looked like the other ones they got.

Blame it all in the Russians [laughs].

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah the Gannett newspapers, regardless of what city, they all look like USA Today.

Roger Black: Well, yeah, and it didn’t used to be the case.

Debra Bishop: I’ve been wondering, maybe you can shed some light on this. How do old brands like Time, Vanity Fair, Vogue, The Atlantic, retain their brand identity in the digital world? What should they be making?

Roger Black: I would have to say that the number one thing is language, in the sense that art directors are working on a kind of visual voice and personality for the magazine. The editors also wanted to create a style, editorial style. Now in the old days, they were dictatorial about that. In the case of H.L. Mencken, he simply rewrote everything. So it sounded like he wanted it.

The New Yorker brought together a group of people who were social friends and/or admirers from across ... who were just mailing in the copy, but they all loved that style. And so The New Yorker sounded like The New Yorker all the time.

When Henry Luce started Time, they rewrote everything and made up words, and the whole thing became very punchy. There were papers like The New York World, and then later the Herald Tribune, that had quite a lot of style and personality.

A World story had to have a certain tone to it. The New York Times ignored all that. It was boring as all hell forever. But I think that starts, the way the headlines are written and all of that stuff is essential. Beyond that, it’s typography.

How do they do it? The answer is always type. Just … you can fill out the rest of your questions very easily. The problem is they’re all using Google. All these newspapers are using Google fonts, and I’m not a huge critic of Google fonts. It’s amazing what they did. They brought 99% of websites into fonts, but I think they developed their library because they didn’t want to spend a lot of money on licensing. They developed the library very quickly. So they’re not all that great.

Patrick Mitchell: You once said when talking about one of your digital publishing startups, “The first to contact us were editors and publishers outside the big groups or refugees from them. These publishers and wannabes are the future of publications. They get social media, crowdsourcing, iterative live content. And the idea that readers increasingly want to participate in a conversation, rather than just sit there and read.”

That’s several years old, but it is where new indie magazines, digital and print, are right now. And they’re doing, maybe in a lot of cases, better than the big publishers. Will it work? Is that the future?

Roger Black: I think it is the future. I think it’s the present. There’s been an enormous emergence of bloggers. My current favorite blogger is an old-time reporter and writer, Lucian Truscott [The Village Voice], who’s live blogging the invasion of Ukraine. And he has an amazing background, but he’s also quite a pungent writer. I mean, we were talking about this yesterday: Who are the Hunter Thompsons or Tom Wolfes of today? There are not that many people who really can deliver very pungent ideas and pungent prose at the same, and Lucian is one.

Patrick Mitchell: And what is he on, Substack, or something like that?

Roger Black: Yeah. But he has his own, you subscribe, or you can’t subscribe. I mean, you can read it for free. And he sends out a newsletter, which he’s constantly updating, and it’s very personal. But he really thinks about it and writes well.

Patrick Mitchell: So he’s a micro magazine.

Roger Black: Yeah. Now he’s not designed. He took a Substack format, I guess. It’s okay. The things that I read now tend to be in print, too. And what’s interesting, that print still exists is interesting, and there tend to be... The successful things, I think, in all of these, are either razor-focused … Do you see Arch Daily? That’s not bad looking. And it’s really interesting. And I don’t know how they produce all this content. It’s a micro focus. It’s a particular kind of modern alternative architecture with a big whiff of green to it. There’s another one, Dezeen. That’s another design and architecture …

Patrick Mitchell: …Yep. It’s really good. Yep.

Roger Black: Now they don’t have print, but then some local things like The Big Bend Sentinel, which is Marfa, Texas, is a website and print, and they put out a weekly. It’s boring as all hell looking, but it’s really good. And it’s surviving.

Patrick Mitchell: Don’t they have their own café too?

Roger Black: They have a very nice café. I recommend it.

Patrick Mitchell: That’s the business model? That’s what Monocle’s doing, in a way.

Roger Black: I think, yeah. I think you have to have a café. Why wouldn’t you?

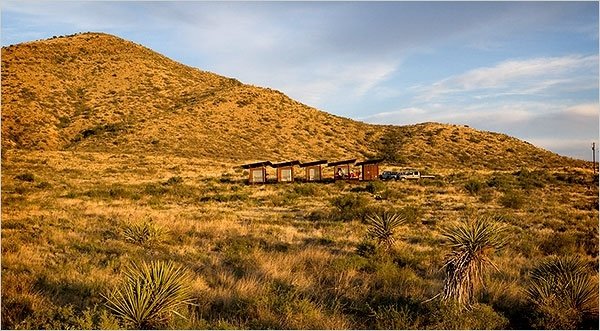

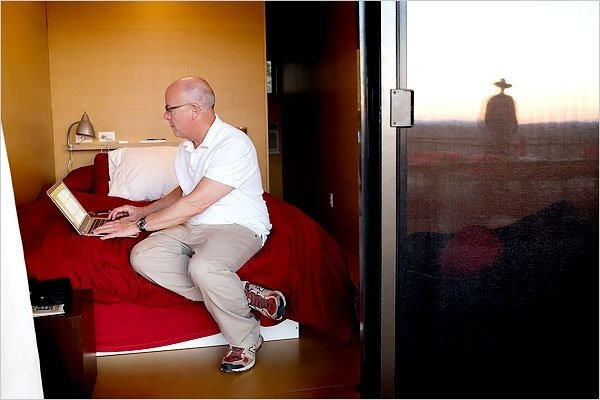

Black’s retreat, Camp Cinco, near Marathon in Texas’ Big Bend country.

Patrick Mitchell: There has been one remarkably consistent theme in the Roger Black story, and that is movement. This is one incredibly integrated work-life philosophy. Movement in life, movement in work. Which one is the driver here?

Roger Black: I think it’s the same thing. I don’t think that there’s a priority. Your work is your life, at least for me. And everything that you do that you don’t think is working helps your brain work when the time comes. So that includes food, or talking to people, or getting around.

I think the coronavirus lockdown has been debilitating for people who like to move, and worse in some places than others. Nevertheless, I have been able to get around a little bit, and I spend, basically, I go out to Texas for a period of time to the ranch, which I’m getting ready to do in April, and try to spend a month there and then do some side trips, and people show up.

And I think that in New York, I was able to have an interesting lunch essentially every day. That was my idea, that lunch should be an important part of your day. Your big meal, and it should last at least two hours.

And you go to a great restaurant — what’s wrong with that?

And then that kind of morphed to doing lunch parties at home, rather than a dinner party. Inviting three or four people to lunch and have a topic and never record anything. And that was fun. So I’m looking forward to that kind of reconvening a little bit. But Foster, my husband, and I are both talking about kind of a major change, getting the hell out of Florida, and restarting a European pattern.

And we’re going to go to Norway and to London to take a look. And so I could imagine living in the countryside near Oslo, and then also at the ranch.

Patrick Mitchell: So no intention to slow down?

Roger Black: Yeah. My dad, who taught me a lot, one of the things he taught me — I mean, this is by example — was just to keep working if you enjoy work. If work and life are the same thing and you like your work, why would you stop? So he continued working every day until he was 80. And then he quit and he only lasted a couple more years. So I figure I’ve got to go until 90.

“My dad, who taught me a lot, one of the things he taught me — I mean, this is by example — was just to keep working if you enjoy work. If work and life are the same thing and you like your work, why would you stop?”

Debra Bishop: What’s the biggest mistake you’ve ever made professionally?

Roger Black: Well, I don’t think it’s a one mistake.

I’m not sure that I could point to it, mainly because I’m the kind of person who always has a reason, can justify anything, and argue himself into whatever reality that he wants. But I would say that there are patterns or kind of syndromes that I wish I didn’t have. So one of those is relative volatility. I mean, this was much worse when I was drinking, but I still get angry. I still, I push people very hard. And part of that is the way, that’s what my parents did, that’s what all my great bosses did: Abe, Lou Silverstein, Jann Wenner. They didn’t cut any corners in terms of making something polite when they wanted to tell you something.

And sometimes they would use — Jann would swear and everything else — but I don't think they would’ve gotten the results otherwise.

So I kind of got some bad habits that way. And nowadays, I couldn’t work in a big corporation, because I’d get canceled out pretty quick, because I would tell them. So it’s very good to own your own company. They then say, “Well, he’s the owner.” And I’m not working in ... I don’t have any direct reports, so there’s nobody I get really mad at.

But I think that would be my worst problem, being too hard, or what would now be regarded as abusive behavior. It doesn’t go over very well. It’s not effective. In the old days, that’s just the way everything was.

Debra Bishop: How would you want to be remembered?

Roger Black: Well, I think it gets back to process. I think that it isn’t the layout, it’s the system, it’s the code. It’s the, What’s moving forward? What’s the logic of the typography or the design structure?

And I think that what I’d like to be remembered for is thinking about the way things move, not the way things are page-by-page. And that makes, that’s why I was able to go into the web so quickly, is that it’s saying, oh yeah, we can move. And I think most people had trouble because they defined everything in terms of a particular shape of a page, eight by eleven or whatever it was.

Since I’m not a painter or not an artist, I never thought of it as a canvas. I always thought about it as, What is the impact you’re making? How are you interacting with whoever is getting it, reading it, or using it? And that’s what I like to be remembered for. Thinking about it as a process and not as a layout.

Patrick Mitchell: Someone like say, Jeff Bezos, comes to you and says, “Roger it’s 2022. Money is no object.” Obviously, for him. “I want you to create a print magazine for our times, the magazine of your dream.” What would you make and who would you make it with?

Roger Black: That’s fun. I love the idea of Bezos, because if he can spend $300 million on a boat, he is being very productive with The Washington Post, by backing the Post. And people said, “Oh, The Washington Post began to decline. Their subscriptions are off.” I don’t know if that’s true. They just hired another 50 people in the newsroom. So I mean, it doesn’t have the level that The New York Times has, but it’s still pretty fantastic, and that’s thanks to Bezos. But what I would like to do, would be to reinvent Life magazine.

The weekly Life had three photo stories, usually one, not hard news, current, one of personality, and then one, some kind of travel log.

I’d like to pair that with three essays, and make a printed edition, and maybe it’s not weekly, but then have a front of the book that is all short takes, and a back of the book that’s got reviews and culture items, just like a classic magazine. And I bet you, if you got ... I mean the thing is, you would have to get great artists and photographers and great writers to do it, but I think you could find them. There are really hundreds of people who I would talk to about doing that if I had the money.

Patrick Mitchell: Who would you hire as the editor? Yourself?

Roger Black: No. I wouldn’t hire me to do anything. I’m past that. That’s a really good question. I’m not...

Patrick Mitchell: … Living or dead…

Roger Black: I think all of us from my group are maybe a little long in the tooth for this, but I’m not sure, I haven’t gotten that far in terms of who would be...

Do you see Susan Zakin’s crazy Journal of the Plague Years? She’s put this together with no money, and she just kind of grabs art. I’m not sure if she’s cleared everything that she runs, but it’s still really entertaining reading and very current. I don’t know if she would be the person, but somebody like that. Somebody who’s out there doing really interesting stuff, probably from the digital side. You could basically ... I think a print edition is sort of a snapshot. It’s like if you do a 20-minute cut of a movie. That’s what the magazine is. But there’s still a movie going on. Except there is no ending, it just keeps going.

For more information, visit Roger Black’s website, follow him on Facebook or Instagram, or visit Type Network.