Soul Survivor

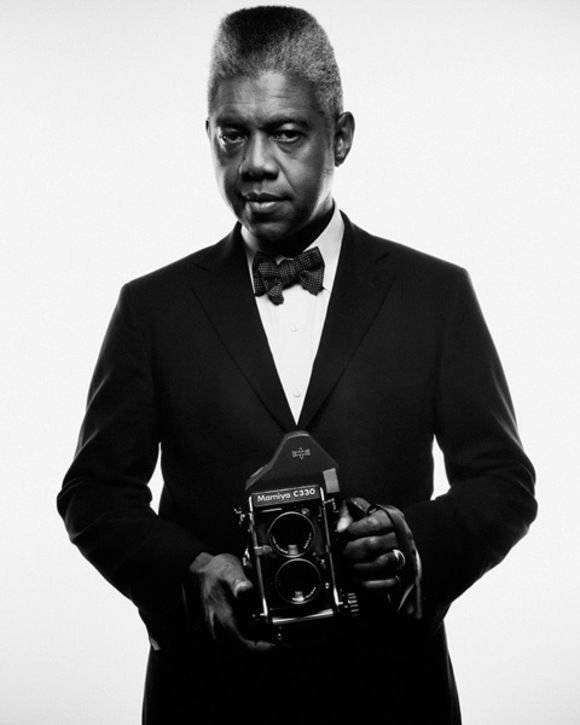

A conversation with designer Richard Baker (Us, Life, Premiere, Inc., more)

—

THIS EPISODE IS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR FRIENDS AT COMMERCIAL TYPE, MOUNTAIN GAZETTE, AND FREEPORT PRESS.

Just about every magazine Richard Baker worked for has died. Even one called Life.

Also dead: The Washington Post Magazine, Vibe, Premiere, and Parade. Another, Saveur, also died, but has recently been resurrected. And Us Magazine? A mere shadow of its former self.

Sadly, Baker’s career narrative is not that uncommon. (That’s why you’re listening to a podcast called Print Is Dead).

But Richard Baker is a survivor. He’s survived immigrating from Jamaica as a kid. He’s survived the sudden and premature loss of three influential and beloved mentors. And he’s survived a near-fatal medical emergency in the New York subway.

Yet, in the face of all that carnage, Richard Baker just keeps on going. To this day, he’s living the magazine dream—“classic edition”—as a designer at a sturdy newsstand publication (Inc. magazine), in a brick-and-mortar office (7 World Trade Center), working with real people, and making something beautiful with ink and paper.

Patrick Mitchell: I would like to start—there’s a lot of interesting things about your life and career—but I want to start with the fact that I believe you were the last art director of the venerable, legendary Life magazine. Is that true?

Richard Baker: Yes, I was. Yes. I am, I was.

Patrick Mitchell: I know that remains, you know, in some weird iterations of collections or special history things, but I would love to just hear you talk about how you got to Life magazine and what Life magazine was at the time. I think you were the last person to be the art director of Life in any sense of a real version of Life magazine—and a really interesting version.

Richard Baker: How’d I get there? I got there when I was probably seven years old. I just remember Life magazine back then. And I didn’t know what it meant. I didn’t understand it. And you’d come across it, especially in school and college, you come across it, you see old issues. So it’s stuck in your mind.

And in an odd way, Carin Goldberg played a little part in getting me there. I got a call from Bill Shapiro. I was at Premiere and it was one of those things where, I’m just gonna stay at Premiere for a while. I have always wanted a place where I could just stay for a while because even to this day, I’m still averaging three-to-four years at a magazine. And I really wanted a place.

So I was at Premiere and I got this call from Bill on the answering machine and I didn’t respond. I had heard through the grapevine that this guy, Bill, was looking for somebody. But he didn’t say what it was for. And I was just like, “Forget it.”

And then Anke [Stohlman], who was working with Carin at the time—

Patrick Mitchell: Anke is your wife.

Richard Baker: Yeah. She said, “Carin said to call Bill. She said that it’s important to call Bill.”

I said, “Why?”

And she said, “He’s looking for somebody at Life.”

And I said, “What the fuck?!”

And I was just like, “Oh, I can’t believe I dropped this!” You know? And I called him—it was on a Friday—and he picked up the phone. He goes, “Yeah, you never called me back. Nice.” And he was like, “Carin talks about you but you never called me back.”

And I said, “Okay, listen, I know that was a big screw up. Give me a shot.”

And he goes, “Okay, here’s the deal: Monday is when I’m making the decision. If you want to show me some stuff, sure.”

And I had this thing for a while where I was never going to do tests for anybody. I had done one before and it went so bad, I was just like, “Screw it.” But my feeling was: “Life calls—what are you going to do?” Right?

So that Monday I got my computer, put some stuff up. It was more about ideas than design. Some of the ideas I stole from Esquire. Remember that thing about Muhammad Ali’s fist, actual size? So I sent it on Sunday. Monday went by. Tuesday went by. Didn’t hear anything. And I went, “Well, I guess I really screwed the pooch on that one.”

And then later in the week he calls me. And he goes, “I really like this stuff.” And he goes, “Why don’t we talk?” And he meets me at this Greek place. And he said, “Look, I really like this stuff, but you never called me back. So I don’t even know why I’m talking to you.”

And I said, “You’re talking to me because I want this thing!”

And so he looked through it. We talked a little bit. He said, “Let me think about this. I really like this stuff.”

And then, like, a day later, he’s like, “Okay, Richard—no pun intended, but you’re the ‘dark horse.’”

Thanks, Bill Shapiro. And so we talked about it. And back then when they used to say, like in terms of budgets, you have a five-year plan. And I said, “How long is the plan?”

And he said, “Five years.”

And I looked at him and said, “Okay, so we have three.”

Because this was around 2004–2005 when the bottom fell out, really. Things were starting to change. And he was like, “Yeah, I give it three years.” But I really liked it. I really enjoyed working with him. I thank Carin, too, because I thought that was so awesome of her to do.

“You have this quintessential magazine. I’m just grateful to be doing it. I’m not there to rip it apart.”

Patrick Mitchell: So Life has come and gone many times. We’ve documented it in the podcast. This time around, it had been gone for a while, and was coming back as a Sunday newspaper magazine to be inserted in newspapers across the country.

Richard Baker: Thirty-six million papers. That was the idea. 36,000,000! And, in a way, that was my second time at bat for Life because I had applied for a job at Life, just for the hell of it, like the week before it folded. I actually went to … oh, what was her name? The wonderful woman who was head of HR? Really short and feisty and just wonderful. Bucky Keady!

Debra Bishop: Oh, Bucky!

Richard Baker: Yeah. So I went to Bucky and I said, “I really want to work for Life.”

And she said, “I’m trying to get you in here. Let’s see what we can do.” And so she introduced me to Martha Nelson who was the, I guess, the über creative director at the time.

Patrick Mitchell: She was the editorial director.

Richard Baker: Yeah. Yes. And so I’m there talking to her: “Blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.” And she’s talking to me about the fashion magazine InStyle. And then all of a sudden we both looked at each other and I said, “Oh no. I’m not here for InStyle. I want to do Life.”

She goes, “Oh. Bucky sent you up here for InStyle!”

I’m like, “No. I want to do Life.” And I think to myself, Am I telling this big-time woman that I don’t want any part of her magazine? What the fuck is wrong with you? And so she introduced me to this gentleman, whose name I can’t remember. I went to his office and I made my spiel.

And he looked at me and he said, “Sounds good, but you know what? We’re shutting it down in a week. You’re probably the first outsider to know this.” And he goes, “But you know what? Come back in about 10 years and make the same pitch. I’m sure somebody will start it up again.

Patrick Mitchell: What was the plan? It was going to be a weekly newspaper magazine—was the approach to continue the same sort of Life magazine that it had always been?

Richard Baker: Well, a couple of things. Aside from the economy, remember, it was maybe four or five years after 9/11. So that was going on. People were very careful about what they would put into a magazine, you know.

You know the magazine business—nobody has any answer, everybody’s guessing what people want to see. And Bill Shapiro—I wasn’t quite sure what he wanted, but when he hired George Pitts, I knew that somehow Bill had this idea that it was going to be, “Yes, we’re going to give the nice stuff.”

And I think the idea was to somehow straddle it so you didn’t take it too far around the curve so that middle America could get it and understand it. And at the same time try not to be too New York, because remember, as Maggie Murphy used to say, “Manhattan is an island off the coast of America.” So you’ve got to be careful about what you put in the magazine.

And I think the idea in his mind was, Yes, we’re bringing it back, but we have to plant it in a place of reality. It can’t be all sugar and candy. And at the same time, it wasn’t quite there yet. But the internet had a lot to play in it.

Patrick Mitchell: Did you go back and look at the history of Life magazine in terms of inspiring the design?

Richard Baker: You know what? I went back and I looked at it and the thing that occurred to me was, it wasn’t a great design magazine. It was a great magazine of ideas with great photography. The design was almost like an ‘accommodation.’ It was a “bit player.” It was important, but it supported the bigger thing.

And when I was doing the cover, it was weird because at one point I was doing the cover and somebody would come up and go, “We should make the logo green!”

I’m like, “What? Do you know what this is? No man, you can’t do that.”

And so I did a little design and the only person that caught on was Carin. On the magazine, if you look at the bottom of the magazine, it had this red bar that went across. And I think either it was the price or the date—it had a little square that went like that. The only thing I did was I made the square round.

And that was it. Because I think that’s all it needed. It’s like you have this quintessential magazine. I’m just grateful to be doing it. I’m not there to rip it apart. And frankly, whatever the new thing was going to be, the design was going to come out of that.

Patrick Mitchell: Its whole value is in what it has always looked like. That’s the reason people keep bringing it back—because it’s Life magazine.

Richard Baker: And yet the value, in a way, hurt it. There was this wonderful editor Bob Sullivan, who had this great knowledge of magazines. And he had been at Time Inc. for a long time and was just smart. And there was another ad guy who I can’t remember, but they had their doubts, and in a real place. And these guys were like, “You think this 24-year-old kid is gonna know what this thing means? I don’t think so.”

And to a certain extent they didn’t understand what this thing was. It’s old media. They weren’t buying into it. These guys were happy to do it, but they saw something. They were very clear-eyed about it. It could go well or it could go south. I don’t think they had any delusions.

Debra Bishop: You grew up in Kingston, Jamaica, and you’ve said that your family was “just north of poor and just south of middle class.” Talk about your early days.

Richard Baker: Oh man! I was going to actually bring a photograph of me when I was like two years old, but I forgot. But I had a pretty decent childhood. It died in my teenage years, but I mostly grew up with my grandma who doted on me because I was the first boy.

And she liked Westerns and that’s why I like Westerns. And she liked movies and that’s why I like movies. And I’d spend the summers down there climbing trees, and making kites, and whatever. And then my parents eventually moved to a place called Caribbean Terrace, which was by the sea, which is my favorite place, even to this day, ever.

We grew up on the beach. We were, like, 25 yards from the water. We were always down at the water. We spent the summers down there. We lived near these hills. And I had a really good group of friends. And we all had pet names. What do you call them?

Debra Bishop: Nicknames. What was your nickname, Richard?

Richard Baker: I had a couple. Nobody called me Richard or Ricky. I actually ended up taking Richard when I moved to America. But my name is Richard Michael Baker. People called me ‘Mickey.’ I had a friend who called me “Baker Buggy.” I don’t know why.

But my best friend was a kid named “Skinny.” And to this day, we’re still in contact and I still call him Skinny. He’s not Skinny anymore, but I still call him Skinny.

Patrick Mitchell: Shout out to Skinny.

Richard Baker: Hey! The reason we called him Skinny was because his name is Andre. And there were two kids named Andre. He was Andre Goodleigh, and this other kid, Andre Kong. And Andre Kong was a big, tall, fat guy. And, I know, this is back in the day, so there was no sensitivity among kids there. So, we’d call big Andre “Fatty.” And we’d call skinny Andre, “Skinny.”

And then we had this song that said, Fatty and Skinny went to bed/Fatty rolled over and Skinny was dead. I don’t know who came up with that. But the thing is those guys didn’t mind. It was their name.

Debra Bishop: So what did your parents do?

Richard Baker: My dad was in advertising. But he came up through the ranks. When he left high school, he went to work for a platemaker that made print plates for newspapers. And then, you know, he learned how to do that as a craft and then learned how to do advertising, make advertising plates, and sort of came up the ranks through the company. And then he became, like, an art director or a design director.

And of course I was just like, “I don’t want to do that. Who the hell wants to be an art director?” And his claim to fame was he and a group worked on this ad campaign that when we were kids, we were like, “Oh, Daddy did that!” It was called “The Best-Dressed Chicken in Town.” It was a chicken with a monocle.

Debra Bishop: Love it. And your mom, what did she do?

Richard Baker: My mom, she worked with him for a little bit at the same company. And then we did the immigrant thing. My mom left and went to America. And the idea was—you know, the immigrant thing—the mother goes, she gets a job, and eventually she makes enough money, sends it back, and eventually kids come up one by one or a couple at a time.

And my older sister and my younger sister, they went up first. And in between that, my parents got divorced because my dad—the idea was that he was supposed to come and he decided he didn’t want to go to America because he felt like it was just not the place for him. And she had made a life. And I stayed back because I wanted to be with my dad for a while. So I stayed for high school.

“I was going to take a pay cut to do this magazine. I was pretty clear about that. It wasn’t about the money. I want to be a part of this.”

Debra Bishop: At a certain point, you came to the conclusion that if you were to stay in Jamaica your options were, uh, rather limited. What were the options?

Richard Baker: My options at the time were working, getting a job with the help of my aunt, at the Royal Jamaican Post Office—they had these cool little red vans—or selling weed. Which was pretty easy. It was accessible and I knew the people who sold weed. But I was never a great student. I went to school for engineering and I could do stuff with my hands.

I was great at drafting and great at making stuff. I was good at algebra and everything else was terrible, you know. Physics sucked. And so I knew I wasn’t going to go to university. Because the University of the West Indies is top notch. And at about that time, I saw what my life could be and I decided, if I want to do something, it’s not going to be here in Jamaica.

Patrick Mitchell: So you told us earlier that you had gotten your high school engineer’s apprentice certificate. How do you go from that to enrolling at the School of Visual Arts in just a couple short years? That’s a big turnaround.

Richard Baker: The thing is that my engineering certificate meant nothing in America.

Patrick Mitchell: Did it have meaning to you in terms of your interest?

Richard Baker: I thought I could get a job as an engineer, at least as an engineer’s apprentice. And they weren’t hiring an engineer apprentice. And the level of work that I know I would have needed to know much more. Basically what I had, essentially, was a certificate for trade school.

And eventually I made my way up to New York. And I think I mentioned I had an accident. You know, I was a messenger. I had an accident, got hit off my bike. And a friend of mine said, “Look, your face is pretty screwed up.” Because I’d fallen on my jaw and stuff.

And he said, “If you go to NYU, they’ll do it for you for free. (Because I didn’t have any money). So I’m walking down there and I’m on 23rd Street and I see this building with people just hanging out. And I’m checking it out. At first I thought it was—I saw the sign and I thought it was a school for the deaf. Then I saw these guys who looked like they just came out of the methadone program. So I thought, Okay.

But then I looked in and there was all this art on the wall. And I was just trying to find something to place my feet in, just give me some interest. Something. I wasn’t ready to sign up for school, like university. I mean, I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do. I went in and there was this guard there and he told me what it was. And, it was art school and, “All you need is a portfolio.”

I didn’t know what a portfolio was. And he said, “Listen, just put some stuff together. Put some art together—some drawings and stuff. Put them in a thing and then just bring them in and maybe get an interview. And you should call them first though.” That’s when there was no email, so I had to call them.

And I got an appointment. And at the time I was taking courses at the School of Art and Design up on Fifth Avenue near the Guggenheim. And I was taking printmaking classes. So the prints I made there I brought with me and showed them. And next thing you know I was enrolled. And then I had to figure out school loans. And I was just like, “Wow, school loans. God, I’m going to be broke for the rest of my life.”

And I went and looked back and I think it was somewhere between $1200–1500. And I thought I was going to be broke forever! Which made me get another job at Gimbal’s department store because I was so afraid I was going to be broke. So that’s how I ended up at the School of Visual Arts.

And I had no idea, honestly, what design was. I actually went to be a painter. But after my first semester of painting, I realized that was not where it was going to be for me. I was just not good at it. And I found it boring. And then I met people who were really good—like people who believed they were going to be painters. And I didn’t have that thing that they had. At all.

Debra Bishop: You studied with Paula Scher, as did I.

Richard Baker: Yes.

Debra Bishop: The eighties was such a special time for graphic design in New York. And we were taught by some of the best. Paula, obviously. And Carin Goldberg.

Richard Baker: Oh, absolutely.

Debra Bishop: Tell us about that.

Richard Baker: Okay, so to get to Paula I took these classes with a guy named Skip Sorvino. And he had this thing where the girls loved him. And I was just like, “Okay. All right.” And he had us do this project. And I didn’t know about design, so I’m doing the project, like, I’m doing the work. And he had us redesign Lotto cards. And I remember making a stat and an emulsion. And you could see through it. And then I had to paint the back of the card. It’s like all this machination, right?

And I remember taking my time and painting it. And I put it in between the cardboard and cut them out and framing it. And put it in my little make-believe portfolio. Eventually Richard Wilde said to me, “You should go take Paula Scher’s class.”

So I go to Paula Scher’s class. And remember, she’s looking through the work of different people just to see what you have. She opens my little thing and she’s like, “All right. You got to get rid of this.”

I’m like, “That took me forever to make!”

And she goes, “What, do you want to make Lotto for the rest of your life?” And she threw it out.

I was like, “Oh my God. Oh my God. My best work.” Yeah. I had the best time.

Patrick Mitchell: If you know Paula Scher, that will surprise no one.

Richard Baker: She’s a tough cookie. But what I loved was, she used to smoke and she would just look at your work. And it was like this: she had this long ash over there. I remember Syndi Becker, she’s, like, looking like this. I’m looking at Syndi’s work, and Syndi is maneuvering, just in case the ash fell, so she could catch it.

Debra Bishop: I remember all of this!

Patrick Mitchell: Paula is the one who decides when the ash falls.

Debra Bishop: Richard, this story was going to come out sooner or later.

Richard Baker: Oh my God, yeah. And, uh, the thing about why I said it ended up me going to her was I was still trying to figure out what this thing was, design. What was this thing? Because I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do, but I thought I had a kind of a knack for it. And I remember we did this thing this series of, I don’t know, images or whatever. We had them put on the wall in the foyer of the building. And Skip Sorvino came over and looked at it and he went, “Oh, you’re doing that Russian constructivist shit.”

Debra Bishop: I had that criticism as well!

Richard Baker: And I thought, I’m gonna stick it out with this woman here. Because essentially I liked what we were doing. The work that I was doing in Skip’s classes was fine, but I felt like if I could look at it with a cold eye now, you might say there was nothing wrong with it. It was very commercial in that way at the time. You might be able to take it to an ad agency as a designer and get a job doing layouts with markers or something like that.

Patrick Mitchell: Your first job was at Koppel & Scher as an intern. Did Paula introduce you to Terry [Koppel]?

Richard Baker: No. I took a class with Terry and somehow he asked me if I wanted an internship.

Patrick Mitchell: Can you just quickly tell people who Terry was to the design world?

Richard Baker: Yeah, Terry Koppel, at the time he was a teacher at the School Visual Arts. But Terry Koppel was—God, how do you describe Terry?—other than the most irreverent designer that I knew. Here’s what I know about Terry: He was brilliant. Really good, brilliant. But all the Jewish words I knew, I learned from Terry.

And I remember when I went home one year, and I was using goyim and shiksa. My mom was just like, “What the … ? What are you talking about?”

And I was just like, “That’s meshuggeneh. Forget it.” Yeah. And I learned all those words from Terry.

Patrick Mitchell: Were he and Paula, was their studio going at that time?

Richard Baker: Yeah. Yeah. They had two studios. The second one I wasn’t there for. But I remember going by there, it was this beautifully fancy studio. The first one was basically a loft. And it was on 26th Street between Sixth and Seventh. And I remember we would come downstairs at night and once-in-a-while the prostitutes would hang out in the corner, waiting for the cop cars to go by.

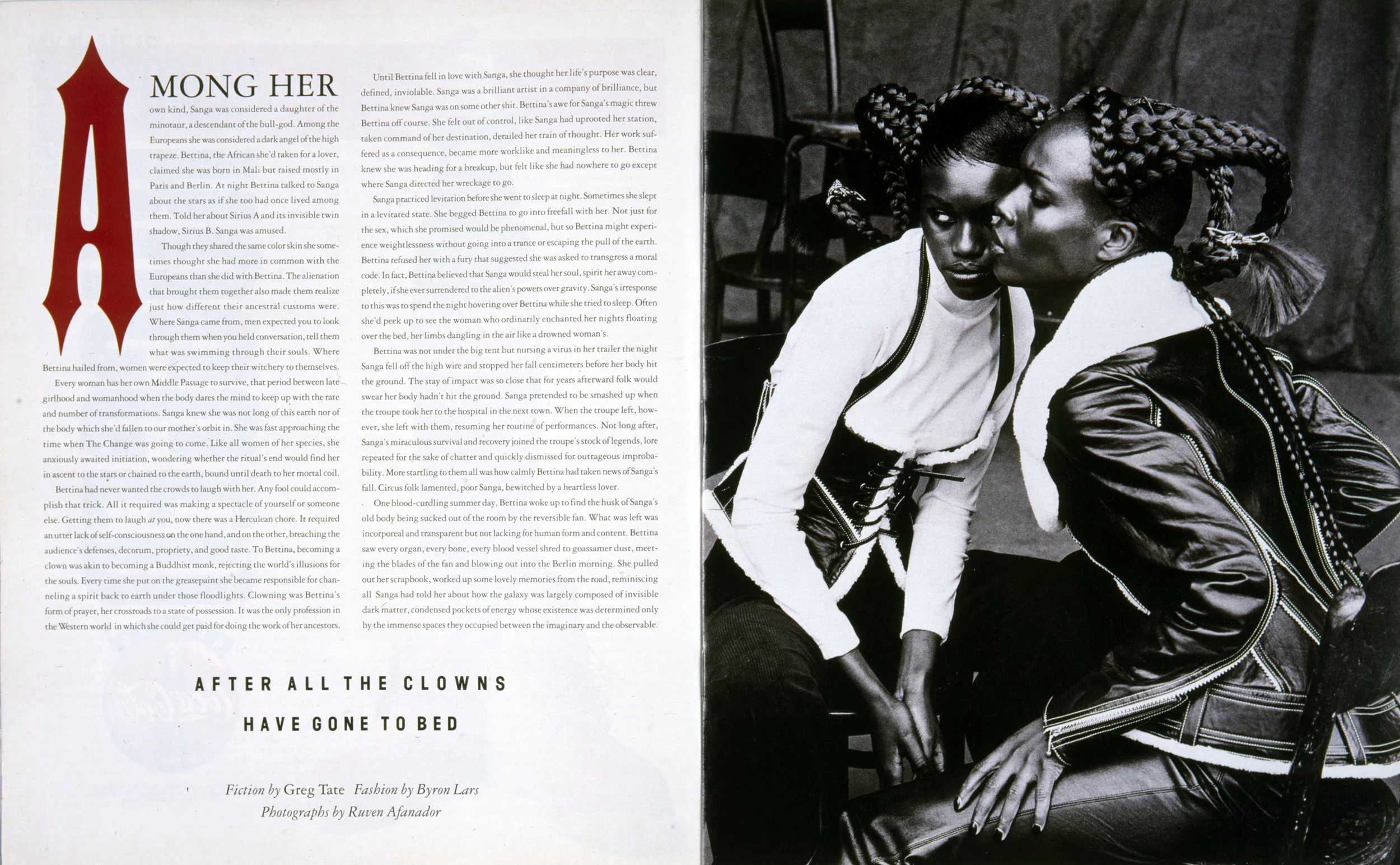

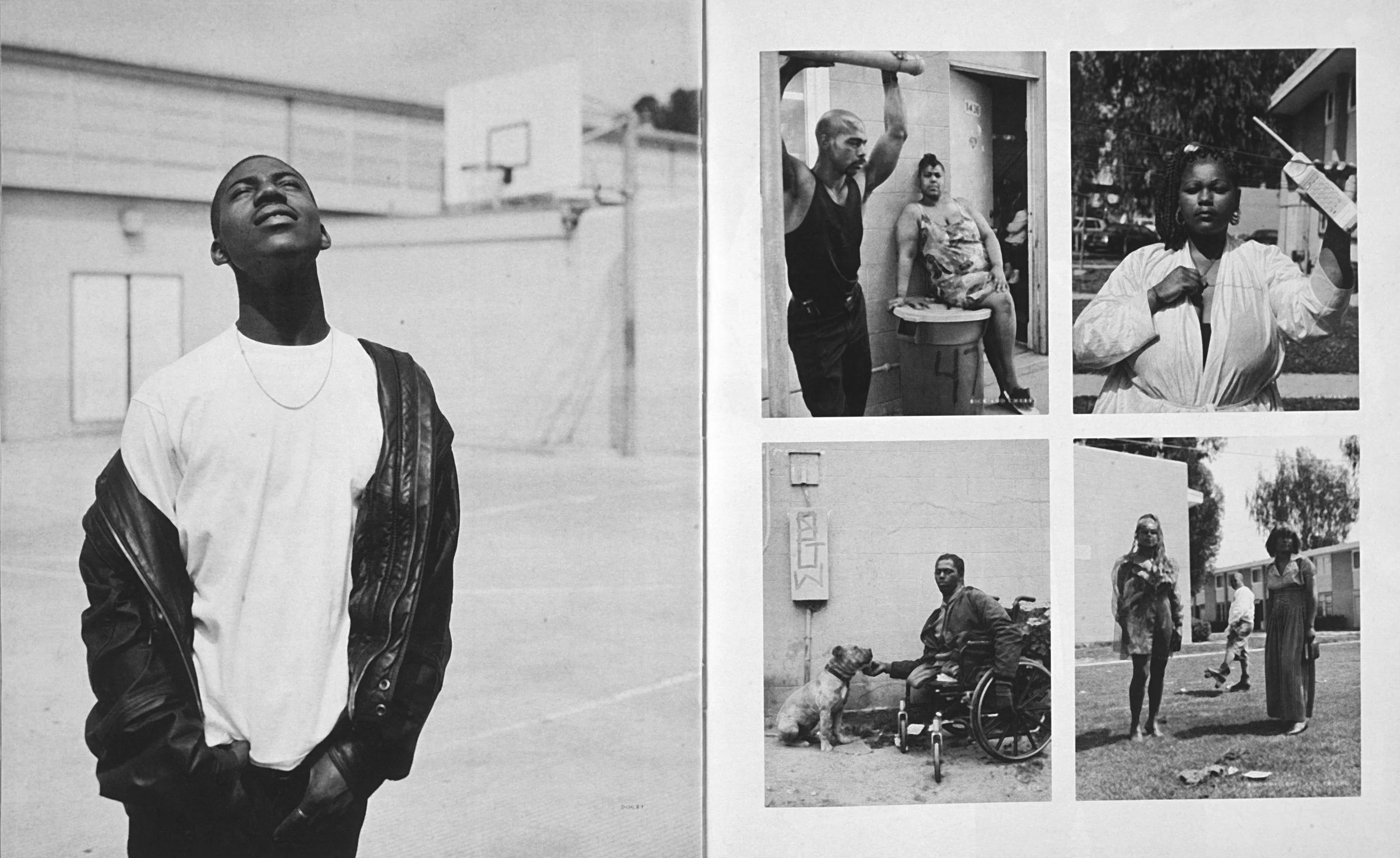

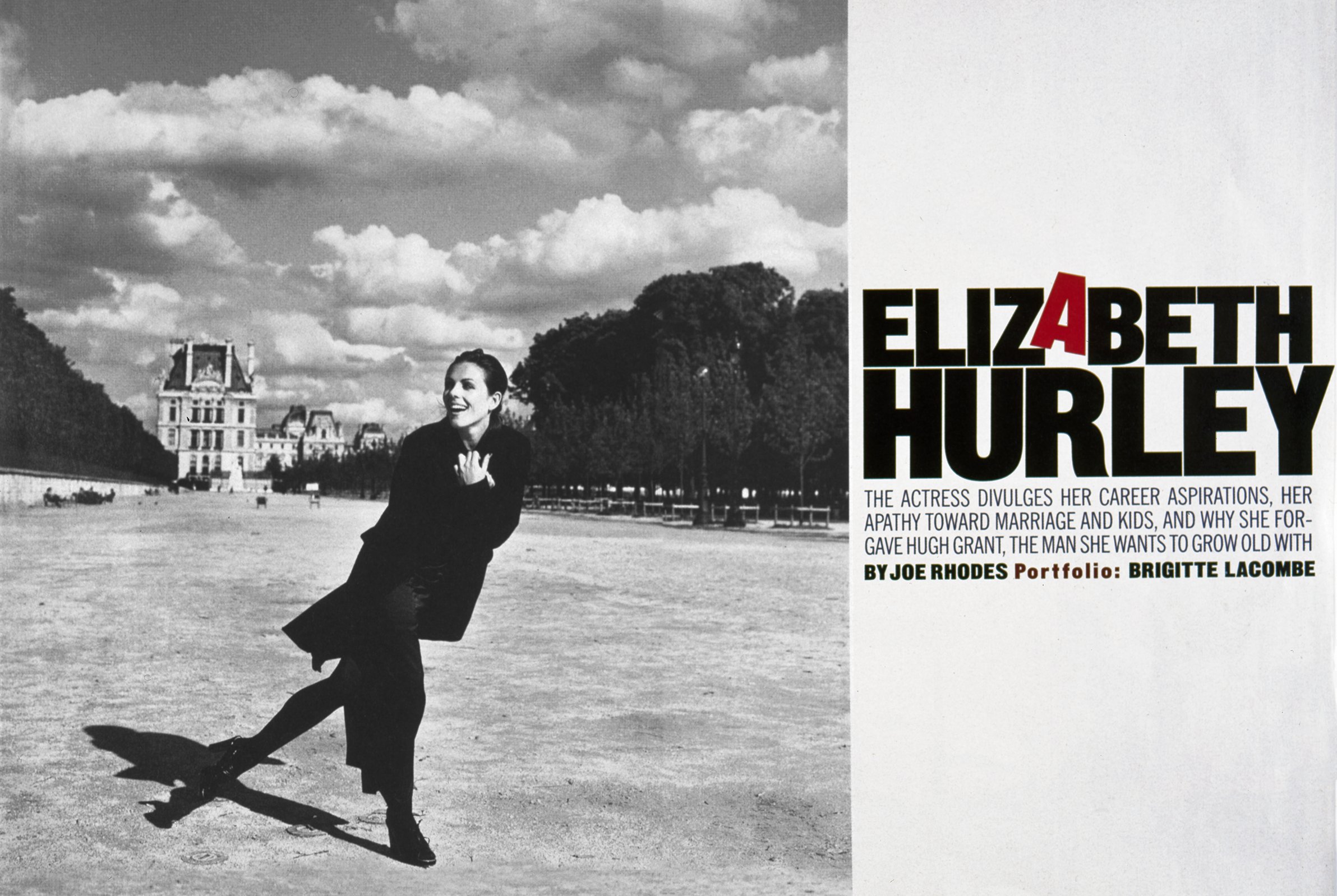

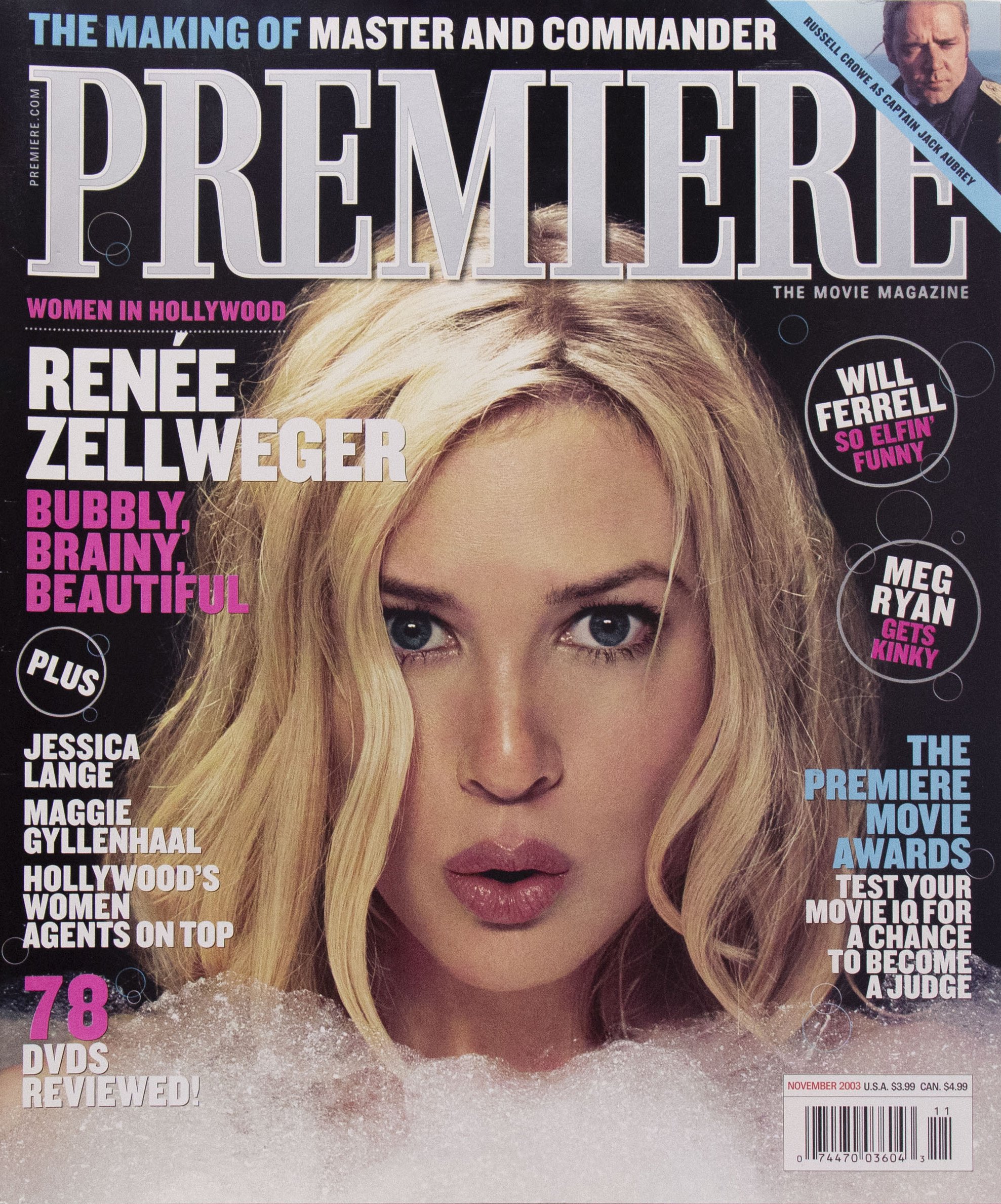

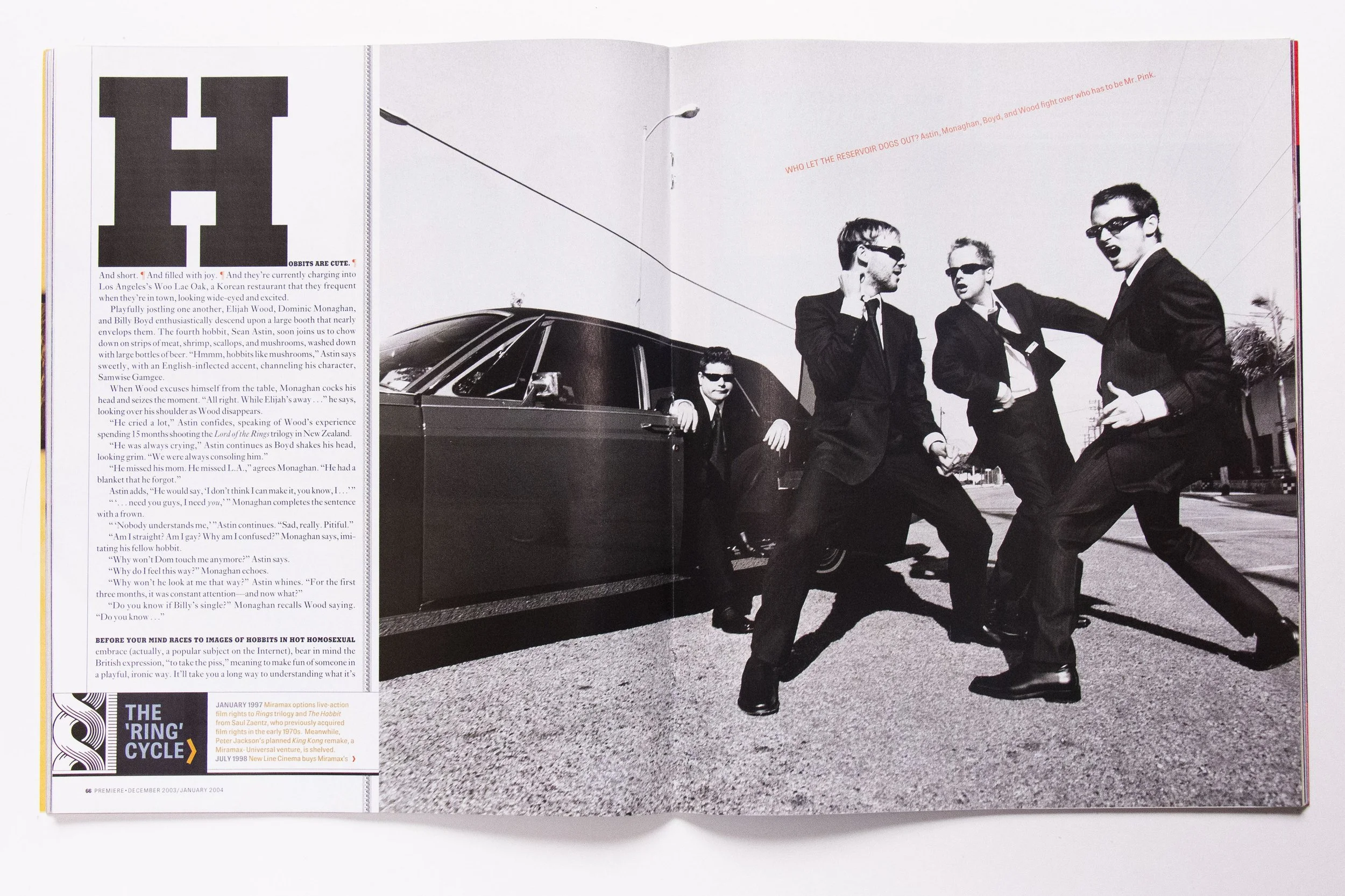

Baker’s Us Magazine portfolio

Debra Bishop: I think there was some sort of, like, massage parlor, too.

Richard Baker: Yeah, exactly, yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: All right, so after your internship, after graduation, You find yourself in Boston and—

Richard Baker: —Again, through Terry. Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: So Terry had worked at The Boston Globe before you came to New York. But talk about the Globe. This is really your first paying job after college, right?

Richard Baker: First job. I was interviewed by Ronn Campisi, who has his own “cone of silence.” You couldn’t get two words out of this guy sometimes. The interview was essentially he takes me out to lunch. We say, maybe, two words the whole time. And the whole time, I’m thinking, I don’t have this job. I don’t have this job because this guy’s not even talking to me.

And he just looks at me and he goes—I’m not kidding—he goes, “You want a job?”

I’m like, “Yeah!”

And he goes, “Okay.” And he says, “It’s about $18–19,000. I thought that was the most money in the world, man!

Patrick Mitchell: What year are we talking about?

Richard Baker: It was about 1984, maybe? Like I thought, are you kidding me? I had part-time jobs at Gimbels department store. I remember taking—because I was so paranoid—whatever money I had, my receipts, I’d keep them and take them to the H&R Block. And I remember the guy was just like, “You make less than $3,000. There’s no reason for you to come down here.”

So I was making nothing. And I thought, This is the most money—and it was—that I’ve ever made. But it was also money that I could send back home. My dad lives in Jamaica, and my grandparents, and I could send them money. And I could give my mom some money or whatever.

Debra Bishop: And you could still afford to have your own apartment?

Richard Baker: I rented a room, a great little room. It was a wonderful little brownstone. And it was a wonderful little place. It was $400 a month. And it was one room. Which was fine because when I moved in there, I literally, and I kid you not, I moved in there, I had one plate, one knife, one fork, one cup, a chair, and a mattress on the floor. The woman was nice. She was like, “I’ll bring up a bed for you. You could use it.” So it was just, like, bare minimum.

But the Globe for me was—it was such a great school. It was a great school in a sense of your first job, you think, “Oh, my God, what is this going to be like?”

Patrick Mitchell: And you’re doing daily stuff, right?

Richard Baker: Mostly I started out just shadowing people. And it was a great group of people like Lucy Bartholomay, you know. And Holly Nixon. And I didn’t even know that people designed newspapers. That was the thing. I was taking the job because I needed the money. And the thing is, honestly, it was out of New York. And I really wanted to get out of New York for a little bit.

Debra Bishop: When we interviewed Gail Anderson, she told us that in addition to great opportunities, basically the Globe presented some difficulties for both of you.

Richard Baker: This was at a time where affirmative action started. And I remember, it was a weird time. And I knew why we were hired to a certain extent. And at the same time, I think we both hoped we had enough chops as young kids. We weren’t without any kind of talent. And I think that was how Ronn wanted to look at it: If I’m going to make this hire under these circumstances, I’m going to hire some really good people.

But, aside from the guys who worked in a print shop, who would call us “colored.” And it was not very long ago that they referred to us as the “colored kids.” But there was one designer who basically was very clear about it. She says, “You only got hired because you guys are black.”

And yet, you know the truth, but you also know, “Yeah, but I can do the work.”

And so you had to deal with that. Neither one of us, Gail or myself, it wasn’t about getting mad or whatever, it’s just doing the work. But what it did offer me was a pleasant place to go to school. The designers I worked with, the ones that I had to deal with and I liked, they brought me through. I learned how to assign an illustration.

And this is a time where you have to talk to the person, they fax you a sketch, the next day it comes in FedEx. And so you learned how to do it quickly, you know. You learned how to make decisions. And I enjoyed it.

And I enjoyed, to a certain extent, listening and sitting at the feet of somebody like Lynn Staley. Or as I said, Lucy Bartholomay. They were, like, really talented people. Plus at the time they were doing such interesting work on the broadsheet. And winning awards. And these are the people I came to admire.

Patrick Mitchell: And actually at the time, the Globe was really considered nationally, like a cutting-edge publication. Like all the work that was coming out of there.

Richard Baker: And the thing is like what they were doing, they were just doing the work. They were doing the work and being creative about it. And I have to say, I have to give Ronn some props, because he was being very fearless at a time where they’re almost like saying, “Yeah, we do newspapers, but we don’t have to do it this way. You can do it that way too.” I felt like I was just lucky to have dropped in at that moment.

Patrick Mitchell: I have to assume, knowing what editors were like in those days, they must have been pretty progressive. Or Ronn must have been incredibly forceful. Or a combination of both.

Richard Baker: It was a combination of both. And in a way, you might even say, to a certain extent it’s not like I was fearless and brave or whatever, but I was clueless. And even in my life of living there, I remember somebody invited me to some dinner at the time in Southie. And I remember taking the bus there and I ended up walking someplace and getting to her house.

And she said, “What are you doing here?”

And I said, “What do you mean?” It’s like me and a bunch of people.

She said, “I said, I’d come pick you up. This is a really bad area for you to be walking through.”

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah, that’s the old Irish section of Boston.

Richard Baker: Yeah. And there were people that I think about now, who really helped me through. There was a designer named Jim Pavlovich, who I’ve always remembered, who died tragically one night. He fell, hit his head, and basically froze in the snow. And I had to work with him. I had to shadow him for a while. And he made a place that I thought could be scary—and he was a grumpy gusset for me, no doubt—but he made it really fun and pleasant.

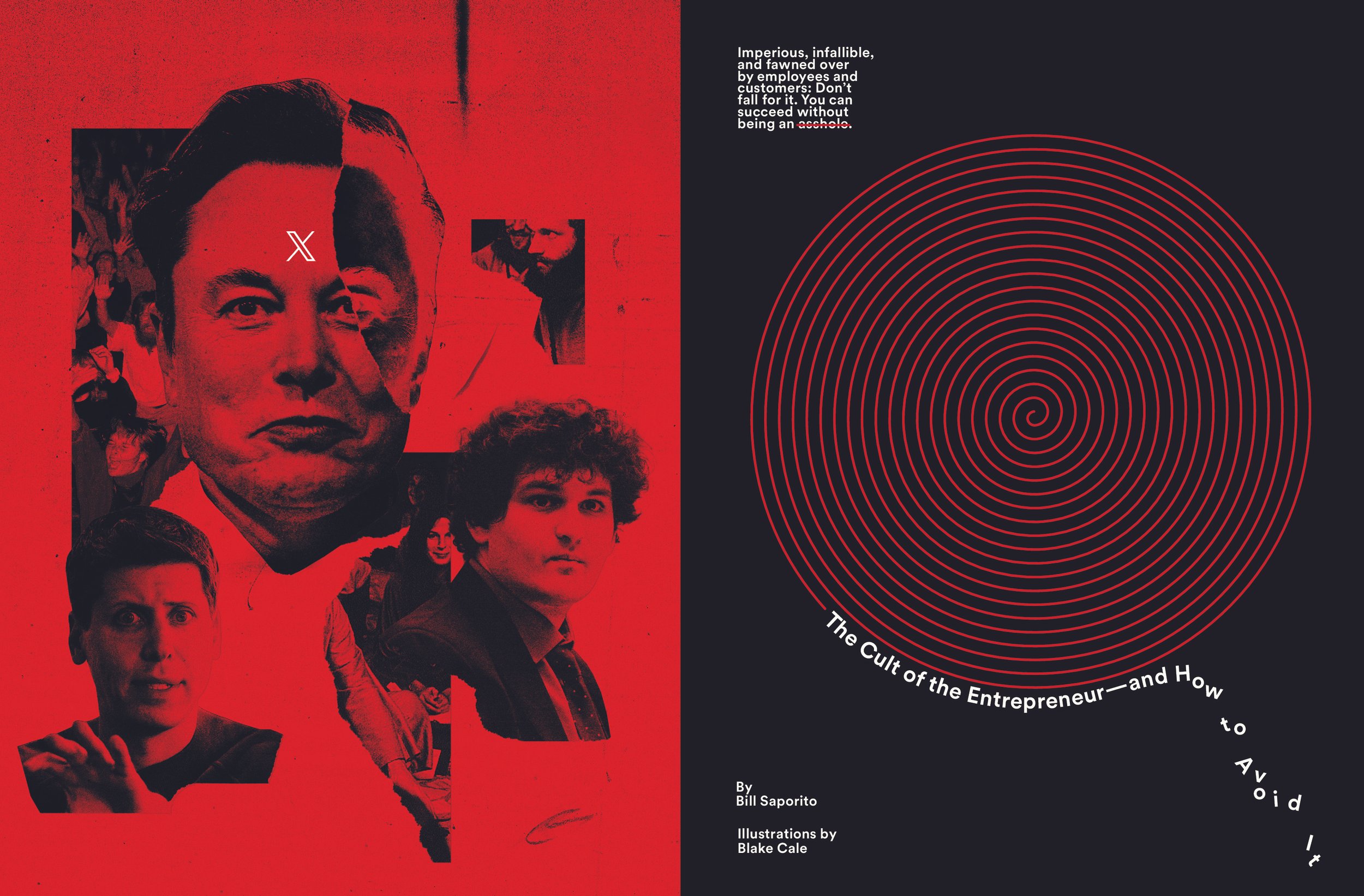

Baker currently serves as the creative director of Inc. magazine

Patrick Mitchell: All right. so you did your time at the Globe—your standard, couple, two or three years.

Richard Baker: Actually, I got exactly 16 months.

Patrick Mitchell: Okay. Short stint for you, but probably because of the next opportunity that came up. You got a call from the Washington Post. And, because I know Sunday magazines from doing them myself, it was another really big deal, what was happening at the Post. They were reinventing their Sunday magazine. They were sizing it down to a newsstand magazine, with great paper and new trim size, and all kinds of possibilities. But talk about that opportunity getting you to Washington. What did they promise you?

Richard Baker: The thing is I had met Michael O’Keefe. He was the creative director for the newspaper. And I had met him at a conference and we had talked and we had gotten along. And I said, “Eventually I want to try something else.” And it was one of those things where you don’t hear from the person—it was just a conversation. And then he called. And he said, “Do you want to come by? Let’s talk about some stuff.”

And I remember getting on the plane, while I was on the plane—and I was going there for the newspaper—while I was on the plane, the magazine was sitting on the seat. With the bar that went like this, The Washington Post. And I was just like, “Oh, this is really cool.” And it felt fat, like a thick magazine.

And so we talked a little bit and he said, “We don’t have anything right now, but I really want to keep you in mind for something.”

And I said, “Okay.” I’m like, “Not for nothing, but I saw your new magazine. I wouldn’t mind working on your magazine.”

And he said, “I think they’re actually looking for somebody.” And so he brought me down to Michael Walsh. And Michael Walsh introduced me to Brian Noyes and to Jay Lovinger, who was the editor at the time, and he was a great guy. And I met with those guys and I think, like, a month or so later, they gave me a call and said, “Do you want to come work for us?”

And I was conflicted because I was actually having a good time in Boston. The only thing that I hated about Boston was the cold. So I went to Washington—and by the time I left Washington, the only thing I hated about Washington was the heat. Because it’s built on a frigging swamp! But the Globe, I wasn’t sure if I’d learned enough yet at the Globe, but I couldn’t give up the opportunity.

Debra Bishop: And so when you got there, you fell in love with the newspaper vibe at the Post. The romance, Ben Bradlee, Woodward and Bernstein, et cetera, et cetera.

Richard Baker: Oh, yeah. You walk into that place and it’s—these guys, like you’ve heard about, you know? It’s like Ben Bradlee. He didn’t look like Jason Robards from All the President’s Men. But you know, when he’d walk down the hall to the magazine, he’d use his fist, like, to bang the cabinets. And they all talk like this: “Hey! Get that son-of-a-bitch up here.”

Debra Bishop: What was your position at that point?

Richard Baker: I was the designer at the time. The number three guy from a three-person team. And the guys were really giving. Michael Walsh was the one I connected with mostly. And he was this designer with, kind of, the “art mind.” It just didn’t come from a pure design place. There was always this little part of art that had to exist in there for him.

Debra Bishop: What do you remember most about working there?

Richard Baker: It made me appreciate the story. It wasn’t just the design. It’s like design didn’t exist without the story, what you could do with it and what the possibilities are. And that even stays with me now that what I’ve always liked is the possibilities.

And what I loved about newspapers is the people: smart, driven. Just real smart people. They can drive you crazy. They can be full of themselves at times, but just so smart. It was almost like going to school, like an education that you missed. And then you came back around and you got how important this thing was.

In the early 90s, The Washington Post introduced a radical redesign of their Sunday magazine by Walter Bernard.

Debra Bishop: There was a standard to uphold.

Richard Baker: Yeah. You had to get it right. I remember we were doing a story about Japanese internment camps. And I’m laying it out and I had this idea of using within the layout, this piece of barbed wire, because the piece talked about a barbed wire around the internment camps. And I liked how it looked.

And I remember Walsh saying to me, “Yeah, but you know what? It’s not what the barbed wire looked like. That’s barbed wire from 1990.” And that’s the thing that I love about it. You can’t muck around. There’s no faking the thing.

Also what I liked about working at the Post—I loved, absolutely loved, the stories, the people, the characters. My first week, they took me to a place called the Post Pub. And you could get a burger. And a lot of the writers would go there. You’d see them working on stories or whatever. And they’re having their lunch.

And I remember the first day I got there and they’re ordering stuff and the waitress comes around to me. And she’s got, like, an old school waitress uniform. And she says, “What do you want?”

And I said, “Can I get a medium burger?”

And she goes, “You get a burger, but you get that the way we make it.”

I was just like, “I love this place.”

Patrick Mitchell: Okay. So after the Post you head back to New York for yet another incredible opportunity to go work with Gary Koepke, who sadly just passed away a couple months ago, at Vibe magazine, but also with the man who would become your hero. George Pitts, who was the photo editor. Let’s talk about Vibe briefly and talk about what getting to work with George meant to you.

Richard Baker: I can’t even remember how I went to see them. But I remember that I was going to take a pay cut to do this magazine. I was pretty clear about that. It wasn’t about the money. I wanted to do this magazine. I want to be a part of this. And Gary was there. And in fact, you know, he did ask, “Are you sure about that?”

I’m like, “Yeah, I’m gonna take a pay cut. It’s okay. I’ve lived on less and I can figure it out.” And I remember the first time I saw George, I thought he was, like, Al Green or something like that.

Patrick Mitchell: Just for our listeners, tell people who George Pitts was.

Richard Baker: Oh, George! George was a little older. George was the smartest black man that I know. Erudite. Somebody said—and I kid you not—somebody said that George walks in the light. And what they meant was, if you’re with George and something good’s going to happen, it’s going to happen there.

He was open. He was an incredibly gifted photographer, self taught. Incredibly gifted painter. Much later in his life, much later that I found out—because he didn’t talk about it—that he had written and published a poem in The Paris Review. Just incredible, this person. And I loved working with him.

Baker’s friend and mentor, George Pitts

And when I went to Vibe—and Vibe is probably the only publication I had conflict with. For a long time, I felt like there was unfinished business there. But If I know anything about photography, it’s all through George. There were things I couldn’t see. And when he talked—and he’d always have a toothpick—and he’d go, “Richard, that’s really novel.” And then not say anything after that.

And, in fact, at one point I said to George—this is going to be embarrassing—but I said to George, “I want you to be my rabbi. If I have a problem, I want to come to you. If I need advice, I’m going to come to you.”

Debra Bishop: What does Bill Shapiro call you?

Richard Baker: Was it Bill? Or Mark Danzig?

Debra Bishop: Oh, Mark Danzig, maybe.

Richard Baker: The “Jamaican Woody Allen.”

Debra Bishop: Yeah.

Richard Baker: But George, he left a mark on me. And I enjoyed working with him just immensely. And even after Vibe, we remained friends. And then when Bill decided to hire George for Life, I’m like, “Sure! This is the guy.” Because photography was photography with George. It wasn’t like, “This is for this. Or this is for that.” And he was a humanist.

Vibe magazine, especially in the first five, six years, owed so much to him. One of the first things that we did, I don’t know if you know the work of Dana Lixenberg. She is a Dutch photographer. And she came to the office at Vibe with this incredible pack of work—photographs of people that she had been working with for years in Watts.

Here’s this white, blonde woman hanging out in Watts, and the work was just amazing. And she brought it and we saw it and I looked at George and I said, “We’re gonna print these. We’re going to print these, right?”

And George was like, “Of course we’re going to print these.”

And she looks at George and she says, “I have to take them to Vanity Fair because they want to see them.”

And George was like, “Vanity Fair is never going to print any of these, forget it. But you should take these to Vanity Fair, though.” Because one of George’s things—George would always say, “Richard, always take a meeting.” And so he says to her, “Go take the meeting, and then when you’re finished, come back to us and we’ll print them for you.”

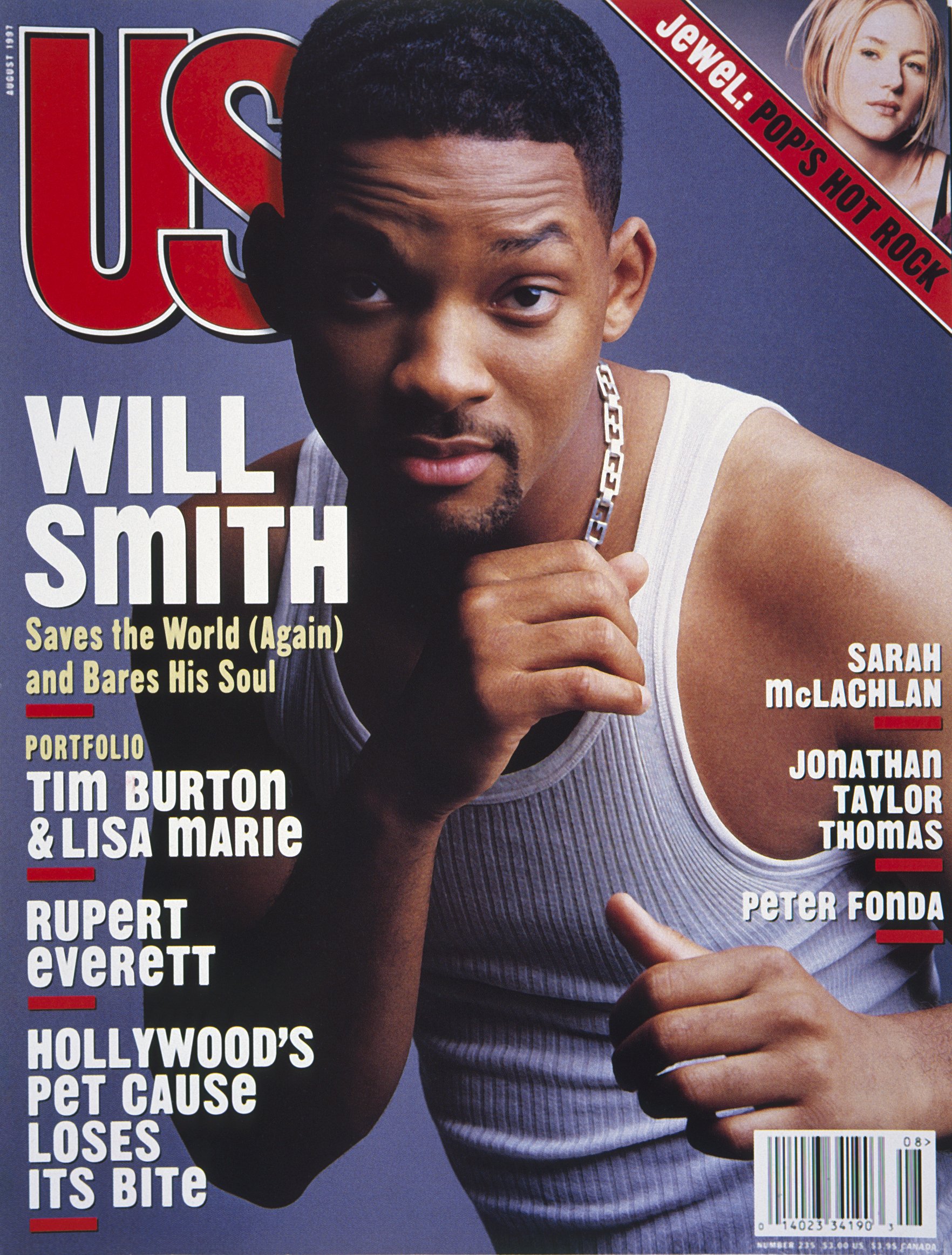

Debra Bishop: Let’s jump ahead to Us Magazine, where it looked like you really hit your stride as a magazine designer.

Richard Baker: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: I’m not quite sure what your title was at that point. Is that the first time that you led an art department?

Richard Baker: That was after Vibe, which didn’t end well. But it made a great transition because after Vibe, I went to work for Janet Froelich at The New York Times. And I’ve always said, if there were five art directors, my favorite art directors, she’s either one or two. And it’s not just the design. I watched her work and the thing like, God, I wish I could work like this person. Just so smart.

And I remember one day sitting in a meeting with her with a bunch of these, you know, New York Times “old-boy” guys, and she just navigated that. And I was just like, “When will she be president? She should go work at the UN or something.” But she helped me at a time when I was just kind of a little bit down in the dumps—to watch somebody do something really well.

Patrick Mitchell: She could do a master class on running an art department.

Richard Baker: Oh absolutely. She’s one of my favorites.

Patrick Mitchell: She’s a great partner and she’s willing to let people go. Let them do their thing.

Richard Baker: Yeah. And I learned that from her. Because somebody gives you a desk and a computer and a couple people around you and you think you know how to do it. Until you see somebody do it, and then you go, “Oh shit!”

Debra Bishop: One of the things that I always thought was very impressive about her was how she dealt with these very intelligent newsroom men.

Richard Baker: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: And was able to collaborate, and persuade, and was able to create great work even under those circumstances. Which is not easy.

Richard Baker: That was the thing that was so impressive to me. Because it’s not about that she was smart and—that’s her, that’s natural—it’s how she could navigate all that. Because there’s smart people who can’t do that. And it was so seamless.

Patrick Mitchell: Graceful.

Richard Baker: Graceful—and herself full of grace. And effortless. And so when I’d gotten to Us—and this was with the help of Gail and Fred [Woodward]. Fred didn’t sign on. And Fred—Deb knows Fred—is not going to sign on with somebody he doesn’t know. He’s got to be convinced that the person can do it. Not even for Gail is he going to do that.

“It’s like being a jazz musician. After a while, the trumpet becomes harder to blow. You can’t make that tune again.”

Patrick Mitchell: Us magazine was owned by Wenner Media, which owned Rolling Stone and Men’s Journal at the time. So Fred was the de facto design chief for the whole company.

Richard Baker: Yeah. And it’s funny because it’s one of the things I felt like that was another school. And I think that if I had gone there first, before I had gone to Vibe, I think I would have survived Vibe longer. I learned a lot at that place. And it’s funny it’s one of those places where people go, “Who was one of your favorite editors to work with?"

And I would say—and Deb is going to be like, “What? Are you out of your goddamn mind?” I would say, Jann [Wenner]. And people go, “What? Have you got Stockholm syndrome? What’s the matter with you?”

Debra Bishop: Jann had incredible taste.

Richard Baker: Look, he owned the store so he could do whatever the hell he wanted. But at the same time, what I did admire at times where there’s a gut feeling. He wasn’t right all the time. And he had his issues that we all know. But I also thought that he was smart about realizing the partner that he had in Fred.

He’s not a business guy. But I would be in an office where you know, we’re sitting around a table and the business guys would be, “Blah, blah, blah.” And Jann would look around and go, “So Fred, what do you think?” And Fred’s not like, gregarious. He’ll just say his thing. And Jann goes, “Yeah, that makes sense. Move on.” So he’d recognize that.

Patrick Mitchell: So were you replacing Robert Priest at Us?

Richard Baker: No. I think Pam Barry had left. She moved to Italy. When I got there her team was still there. I inherited these two wonderful photo editors, Rachel Knepfer and Jennifer Crandall. And with Jennifer, I felt like I was in the fifties or something. “Darling. Oh, please, darling, no.”

I’ll tell you, that series of work that I did, with the big type, that would not have happened—and I really mean this—would not have happened if Jann didn’t listen to Fred. I had this idea, and the idea was, “Why write the headlines the same way all the time?”

You’re gonna write the same stupid headlines. It’s always, “Hanging with blah, blah, blah.” Or, “The Life of yada.” Why not just use their names big? And in the deck, you do your whatever, blah, blah, blah. And I could say that, but I couldn’t sell it. There’s no way I could. Fred’s the one that sold it.

Debra Bishop: He did sell it because we used to do that at Rolling Stone.

Richard Baker: Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: So Richard it’s funny—having now gone through your whole path to getting to Us magazine—it’s funny how you can see all of that come back out when you were at Us. I see Paula Scher. I see Terry Koppel and the way he used to have fun with type and his personality. I see Gary being cutting edge. And your understanding of photography, learning from George Pitts. And working at weeklies. Us was a weekly at the time?

Richard Baker: It became a weekly after I left.

Patrick Mitchell: Okay. And all of these steps of your career, they manifested themselves in your design at Us, which proceeded to go on and win a ton of awards. It was in all the design annuals. Several issues of yours every year would win tons of awards. I don’t think Us has ever looked as good since. It began its downfall long after you were gone to become basically a supermarket tabloid. But just talk about—from an outsider looking in, I see it as you finding yourself and expressing it through your work.

Richard Baker: It’s a little bit of both. Obviously, if you look at Us, its inspiration came out of Miles Reid’s jazz records.

Patrick Mitchell: We’re talking Blue Note Records, basically?

Richard Baker: Yeah. All that Blue Note, Miles Reid, all that stuff. And he was still, I think, an unsung designer. And I have those records. And I’ve always loved them because my dad kept them. And, I enjoyed doing it and playing with it and then riffing on it. The idea that you can riff on it and make it your own. But at the same time, it’s like people like the work you do, and I appreciate it, but it feels like what have I done lately that makes sense?

And even when I left there and went to Premiere—I mostly went to Premiere so I just could get away from Us. Because it was becoming a weekly. And to be honest, yes it didn’t look as good, but it made more money. And ultimately isn’t that what a magazine is for? It’s a commercial venture. And so my feeling was, when I saw that coming, it’s either you stay or you get out of the way. It’s not my magazine. It’s Jann’s magazine.

And as much as I enjoyed it, what I did enjoy about that place is the people I worked with. I really did. Such characters, and the stuff that happened. But I could see this change happening where it wasn’t going to be as much fun.

Debra Bishop: Yeah. I mean things were changing. I left to have a child. But I think things were steadily changing after that.

Richard Baker: Because I’d seen you guys working and you guys were doing this fantastic—I still remember there’s this wonderful thing you did with an arrow, and, I think, it might have been a big “O” or whatever. It was just beautiful.

Debra Bishop: It was a “C” shaped like an arrow.

Richard Baker: Yes.

Debra Bishop: For Kevin Costner.

Richard Baker: And I felt so privileged to be in this place where, down the hall, were this group of incredible designers. How could you not be inspired? And up the street, was David Armario and before him, Mark Danzig. And I have to admit, we were all feeding off what was going on down at Rolling Stone. But what I think was good was that the guy who owned the magazine allowed it. For whatever reason, he allowed that to happen.

Debra Bishop: It’s true.

Richard Baker: For all that fantastic work to come out.

Debra Bishop: And it was such a golden age.

Richard Baker: It was.

Debra Bishop: At all of Wenner Media. It was Straight Arrow Publishing then.

Richard Baker: To a certain extent I have a difficult time talking about this stuff, because it was such a great time. And I look at the work that I see. And it’s like being a jazz musician. After a while, the trumpet becomes harder to blow. You can’t make that tune again. You can’t hit that note after a while.

Debra Bishop: Okay. So once you finished at Us, you went on to Premiere, and then you went on to Saveur. But Saveur must have been quite a change, because this was food and shelter.

Richard Baker: And at the same time, I felt it was food, it was shelter. I still believe designers, that’s why we’re there. We solve problems. Better still, if you have taste, you can solve it better. My grandmother always said, “Good manners and taste, they’ll get you anywhere.”

Patrick Mitchell: Did you have to get into the nitty gritty of food photography, which is an incredibly super specialty?

Richard Baker: I had a wonderful photo editor there and she helped. Immensely. Michelle Heimermann. And she helped me get to that place. But I enjoy the difference. And to be honest, there was a period of time when I wanted nothing to do with any more celebrities. I don’t want to see them. I don’t want to hear them. I don’t want to hear their whining. At that point, I started looking for something different.

Debra Bishop: Let’s just talk about where we are now. We’ve lost a lot of magazines.

Richard Baker: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: And you’ve certainly seen your share of magazine deaths—as have I. Yet we’re still surviving, still making a living. On staff with real magazines. Let’s just talk about the changes that you feel have happened during this time. There’ve been a lot.

Richard Baker: I’ll tell you one thing—as you said I’ve seen a lot of magazine deaths—when Scott [Omelianuk] was hiring me for Inc., I said, “I’m going to be very open with you. Just about every magazine where I’ve been has died. So, essentially, I should be looking at you with a shroud and a sickle.”

Patrick Mitchell: You were the Grim Reaper?

Richard Baker: Yes. I am The Grim Reaper of magazines. So be careful. This is before he even said, “Yes.”

Debra Bishop: Yes, but we’re all Grim Reapers. You made the list. Do you find it harder these days, as I do, to be courageous, to be the same design director that you’ve always been?

Richard Baker: It’s in that place where it’s like everything means something. To editors anyway. “Don’t do this because Florence in New Jersey might not like that. Don’t do that because Ezekiel in West Virginia is just going to hate that.” And some of it could be legitimate.

I remember at Life we had put Catherine Zeta-Jones on the cover. And we got a letter from somebody that said, “How can you put that crackhead whore on the cover?” And that was the thing where, when I thought—the Jann thing—it’s like gravity left the building. A kind of sense of, Can you take a chance here? And the thing that people take chances on—they’re not chances. Not really. Not after they have basically put it through the machine and tested 10 million times. That’s not taking a risk.

Patrick Mitchell: In a way it seems like with the focus on digital, and social, and mobile and all that, would I be wrong in assuming that there’s less pressure on the print that there would be maybe more opportunities to experiment?

Richard Baker: From where I sit, on our magazine, I think there might be less. Our business model is a little different because we have several issues a year, and it's a legitimate magazine. But all at the same time, it’s not like pure print anymore, magazine anymore. It’s used as another vehicle within the company, part of the ecosystem.

But I’m very hopeful about it because I don’t think the technology has caught up yet with the possibilities of what can be done. But at the same time, I think when you’re hemmed in by parameters, you get creative. The issue is, as I see it right now, it’s hard to break and get those possibilities going because a lot of magazines want you to do that with as little as possible.

Debra Bishop: And very little risk.

Richard Baker: Yeah ... and very little risk. And the thing I don’t think they understand is because it’s digital it doesn’t mean that you need less time. There’s this weird fallacy that happens that because it’s digital, it shouldn’t take that long. You’re still thinking. You’re still a thinking person. You still have to create it. It’s only a tool. That’s what it is. It’s a tool. And I am convinced that you can be as creative as you are in print, but you need the support. You need people to take a chance on you to take that risk.

Patrick Mitchell: All right Richard, I want to wrap by asking if you would be so kind as to share the story of an event that changed everything for you. I think it’s very uplifting, the lesson you learned in this process of what’s important and what’s not important. It’s an inspiring and terrifying story.

Richard Baker: So in 2008, Terry [Koppel] and I had just sort of formed an informal partnership. I was working at his house in Brooklyn. That was his office. And one night I left. And I have to say, there are parts not even I remember. All I remember is leaving, getting on the train—and this was January 15th, maybe. It’s whenever the “Miracle on the Hudson” happened. I can’t remember. And then waking up, like, a week later in the hospital.

I had what they call a “sudden cardiac death.” And what it means is your heart stopped beating. And sometimes you get out and sometimes you don’t. And the scary thing, I thought, was not me, but the fact that my daughter at the time—I think she was probably two years old—that the police showed up at my door, and they said, “We have this wallet and we have this address. We need you to come with us.”

And the funniest thing was Anke said Luna really liked the sirens on the car. She liked it. And, in any case, I was born with a defective valve. And every doctor I went to said, “Oh, you have a murmur. You have a murmur.”

And then, at one point, a couple of months before, I went to a doctor on the Upper East Side, and he said, “This kind of sounds funny. We should take a look at it later in the year.” And somewhere between that and that, that’s where I ended up.

And the good thing was—it’s weird. This is how it was told to me by several people: I passed out on the train. I’m lying face down. The cops come around. As somebody put it, they thought I was drunk, or something. Or on drugs or whatever. And an EMT worker who was coming from the Miracle on the Hudson. She sees me there. She sees the commotion. She goes up and goes, “What’s going on?” She sees the cops, and she looks down and she says to the cop, “He’s turning blue. He’s having some sort of attack. Go get a defibrillator.” And she sends him out.

And because of her efforts, they got me in an ambulance really quickly. When I get there, they call my wife. My wife and my child got to the hospital. Poor Anke is not even sure what to do. And there are two doctors, an older doctor and a younger doctor. The younger doctor said, “Look, there’s this thing now where when this happens, a person [is put] in a cold bath, into a bed of ice, to slow things down.”

The old doctor said, “Listen, he might just get out of it.”

Anke doesn’t know what to do. She calls her brother, who is a neurologist. And he says, “Stick him in the ice.”

And I’m assuming that may have helped me. So they stuck me in the ice. And I was there for a couple of days. And I eventually woke up. According to Anke, she said, one day I just got up and looked around. And I looked at her and she was on the computer. And she said I looked at the computer and said, “What a wonderful machine. What is that thing?”

And she thought, “Oh my God! His brain is gone. She was just like balling.

Debra Bishop: Oh, what a story!

Richard Baker: Yeah. And then after that, I don’t know, things changed. It changed how I dealt with people and how I worked with people. And somehow the design didn’t seem as—it’s still important to me, but important in a different way. But what became important to me is how I work with people and I see it in myself. I have a group of people that I work with. And it’s all diversity. And I’ve always been doing that anyway. And they’re all diverse. But what’s important to me is, like, to become better people or something. That’s what’s important to me.

Debra Bishop: The process?

Richard Baker: It’s the process and it’s working with them. And because they’re much younger it’s almost like, you know, my kids. But it’s whatever I can do to help somebody get on their way from here to there. Because at the beginning, after that attack, I had thought that it was over for me. I didn’t know what I was going to do. I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do. The thing with Terry and myself collapsed, and not in a good way. Because I really didn’t know what I wanted to do.

Debra Bishop: At what stage was that? Was that while you were working at Saveur?

Richard Baker: This was before Saveur. And it’s funny because I took Saveur because I needed to feed my family. But I don’t know if my heart was in it. And after Saveur, I decided, Let me see if I can do something that makes sense, that offers some kind of contribution. And so I went to Foreign Affairs. It was political, there were no celebrities, it was about exposing people to what was going on in the world. And yet, that didn’t pan out as much either. It didn’t. Yeah, so I guess I’m still looking.

Patrick Mitchell: It’s interesting. When you first told us that story, I was thinking about how—and I’m sure all three of us are guilty. I think it’s a generational thing. It’s also a sort of creative obsession thing. The way we have all always sweated what normal people would think is pointless. It’s just, “Really? You’re going to sweat designing a caption to go next to a photo?” And when something like that happens—you were dead, briefly, but—

Richard Baker: Yeah. That’s the thing!

Patrick Mitchell: But the industry we’re in recycles that mentality of, Everything’s so important, and it’s so urgent, and it’s going to cost me my job if I don’t get it and other people will see my mistake. And I’m curious—so that was 2008, 2009—you come back to work really a changed man in a really changed industry at that point. And you’re now, I’m sure working with a bunch of, I don’t know, millennials, Gen Z’s or whatever. We have a completely different relationship to work.

Richard Baker: Completely.

Patrick Mitchell: It’s completely different, but I would say it’s veering towards healthy. But so I just wonder, because we’re all sort of the same age, I wonder what it’s like. Because I have not been working in a company in quite some time and I wonder if the combination of your looking at life differently and their looking at life differently, what’s the day-to-day like in a magazine environment anymore?

Richard Baker: First of all, it’s not even a magazine environment. It’s just work. Because it’s all one thing now. There’s no separation between digital platforms and—

Patrick Mitchell: —and between advertising and everything else.

Richard Baker: They feed each other. But I still like the idea of trying to be creative. It’s trying to bend the spoon as in The Matrix. How can you make this thing happen and still make it be lovely? And the thing I learned is, I think mentorship is important.

And I say that because sometimes mentorship doesn’t mean like somebody you have to sit next to or whatever. Sometimes it’s a matter of learning something from somebody. And sometimes that mentor is younger than who you are. And some of those people that I work with who are younger, I’m learning from them as much as they’re learning from me.

There’s a saying from Gil-Scott Heron who says, “Mentorship is important because sometimes the dream you’re in is not your own.” And I love that. It’s like whatever you do could come from somewhere else. And it keeps me hopeful. It keeps me hopeful.

More from Print Is Dead (Long Live Print!)