Design for the People

In this special episode we meet the creators of the 1980s/90s interior design juggernaut, Metropolitan Home: editor Dorothy Kalins and designer Don Morris.

For me, the 1980s comes down to two things: The Nakamichi RX-505 Cassette Deck and Metropolitan Home magazine.

First, the gear.

The Nakamichi RX-505 was an audiophile’s wet dream. It was prominently featured in the steamy 1986 film, 9½ Weeks. In a scene from that movie, Mickey Rourke walks Kim Basinger into his monochrome Hell’s Kitchen penthouse, where she glides through a living room full of furniture by Marcel Breuer, Richard Meier, and Charles Rennie Mackintosh. In the middle of it all, the Nakamichi opens, flips the Brian Eno cassette, and closes, automatically.

And now, the magazine.

Eighties movies featured a slew of inspirational apartments: Tom Hanks’ Soho loft in Big, Judd Nelson and Ally Sheedy’s Georgetown pad in St. Elmo’s Fire, Billy Crystal’s East Village flat in When Harry Met Sally. So when apartment dwellers from Des Moines to Manhattan asked themselves “How can I make my apartment look like the ones in the movies,” they turned to Met Home.

While the old guard, House & Garden, Architectural Digest, and House Beautiful, relished in displaying palatial estates and lavish celebrity spreads, Met Home was the design inspiration for the rest of us.

By the mid-80s — thanks to today’s guests: editor Dorothy Kalins and designer Don Morris — Met Home was the best-selling shelter magazine in America, boasting a higher circulation than all of them.

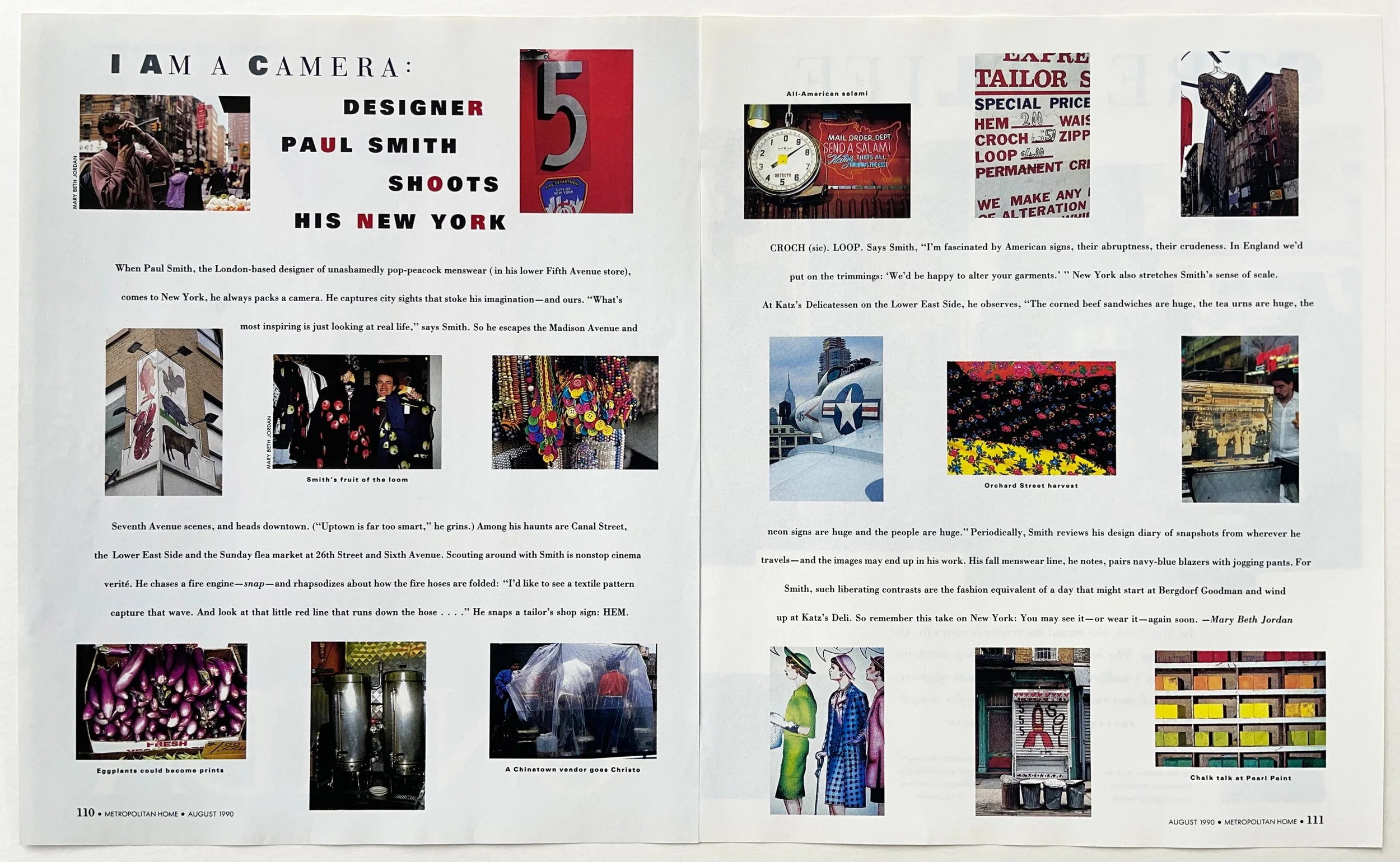

It was a magazine rich with design and lifestyle inspiration and beautiful apartments and houses, but Met Home was not a typical decorating magazine. Its stories were very personal and captured its subjects’ individual passion for the things that surrounded them.

But it didn’t last long. By the early 90s, thanks to a recession, Meredith sold Met Home to Hachette, who out-bid Jann Wenner’s Straight Arrow Publishers for the magazine. Hachette, though, was more focused on its own shelter book, Elle Decor, and left Met Home to languish and fade.

Kalins and Morris were gone, each off on their own new adventures.

For many of us, Metropolitan Home was a special magazine from a special time. A hopeful time. We were moving out — to dorms, first apartments, or starter homes. We bought affordable modern furniture from a brand-new Swedish big-box store called Ikea. We drank the New Coke while we played Donkey Kong on our Nintendos. We sang along with “We Are the World.” We watched Top Gun — the original — on our VCRs. And we paid an average of $375 (!!) a month for our rent.

Met Home gave its intrepid readers permission to indulge themselves in creating their own home design. And, as Morris says, “We helped expose people to a lot of design trends, but also gave them a sense of how they might be able to bring that into their own lives.”

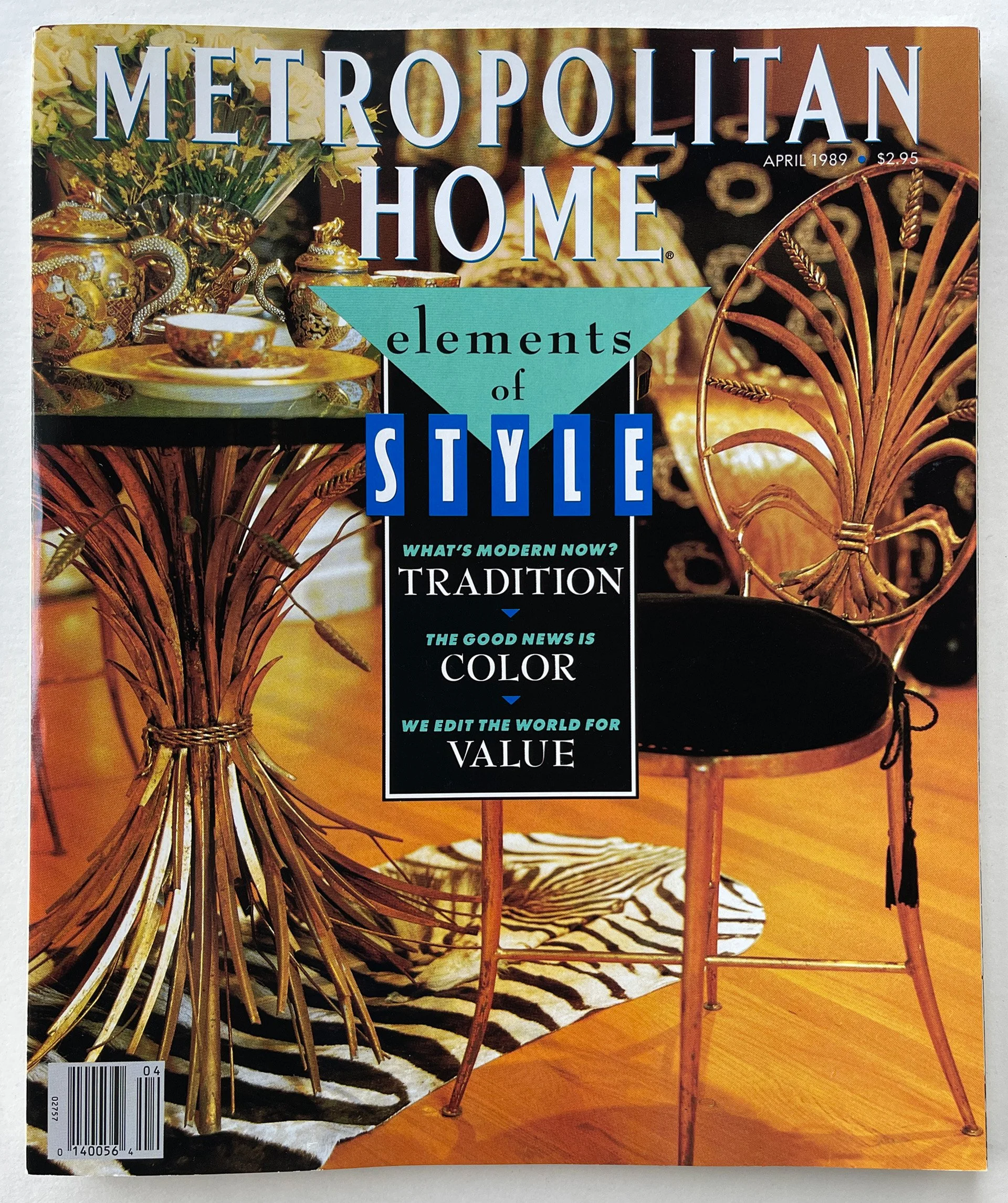

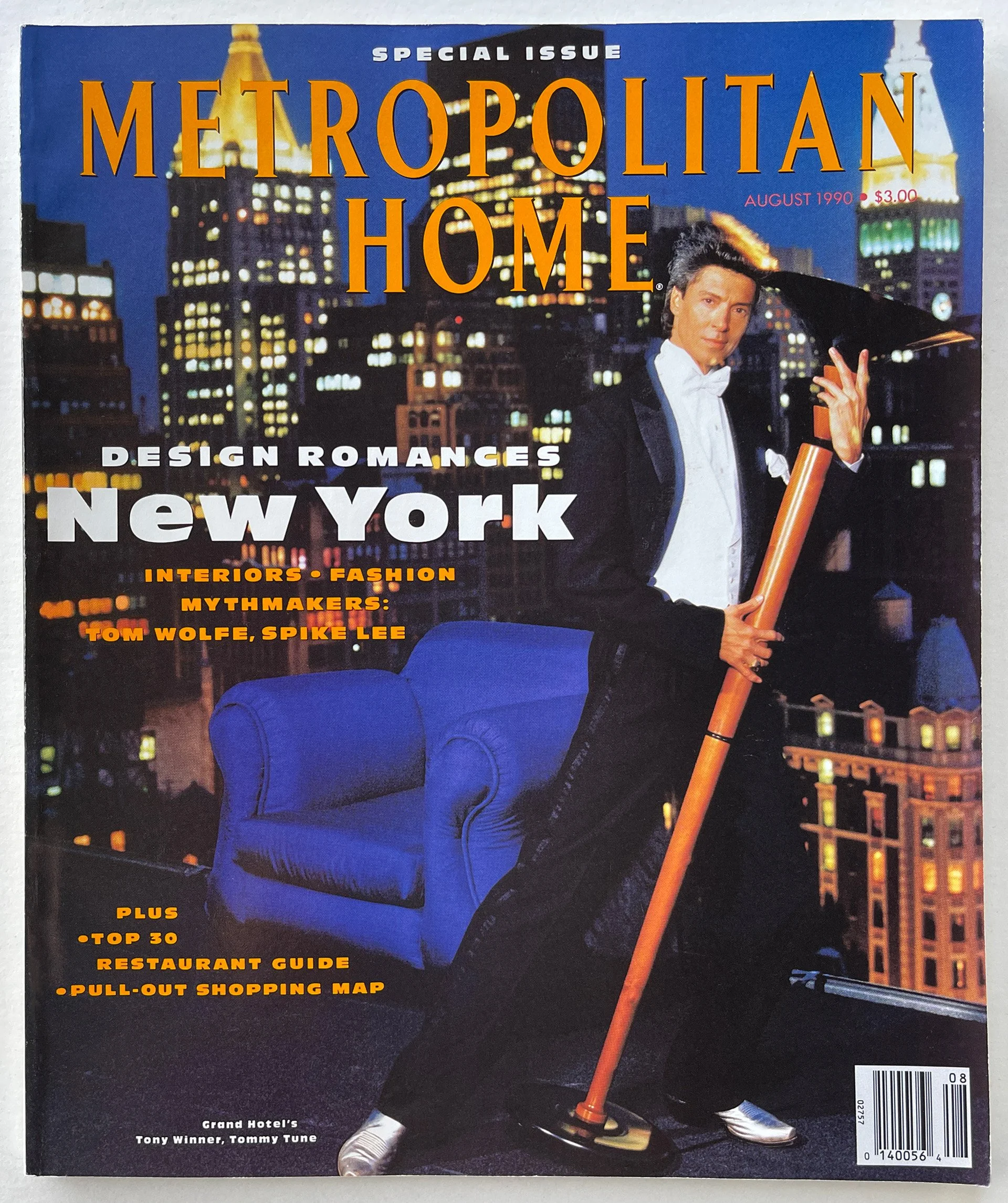

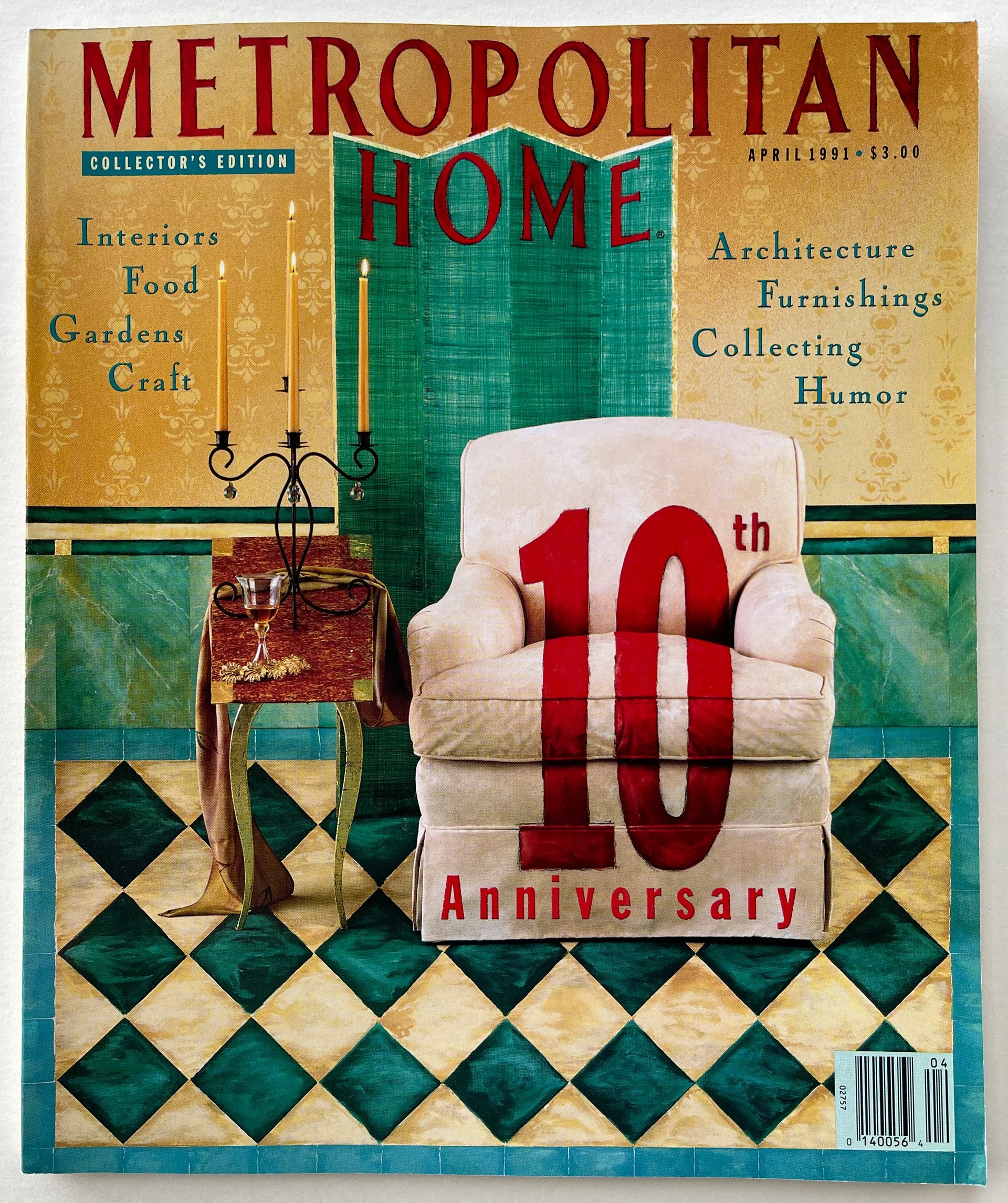

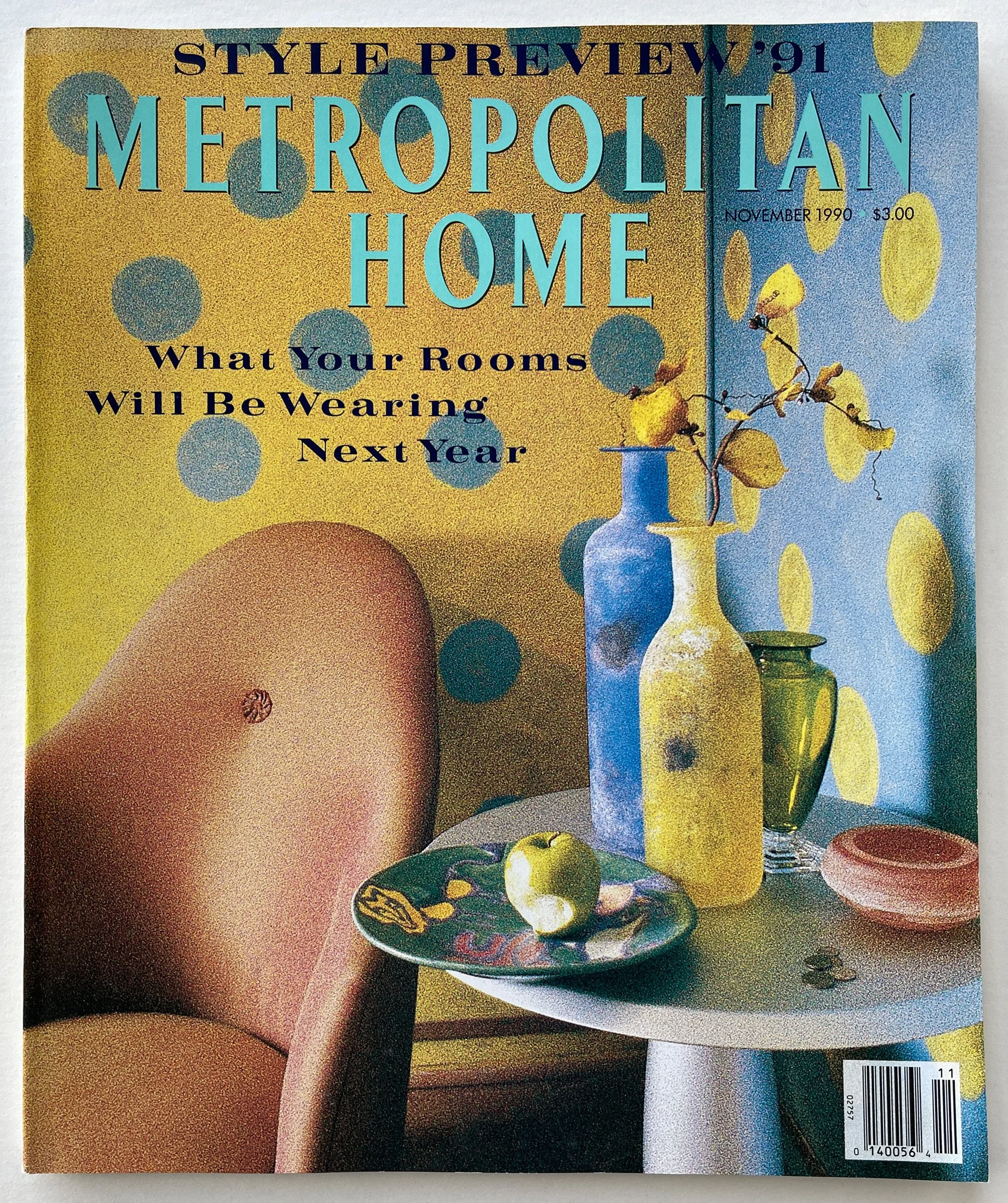

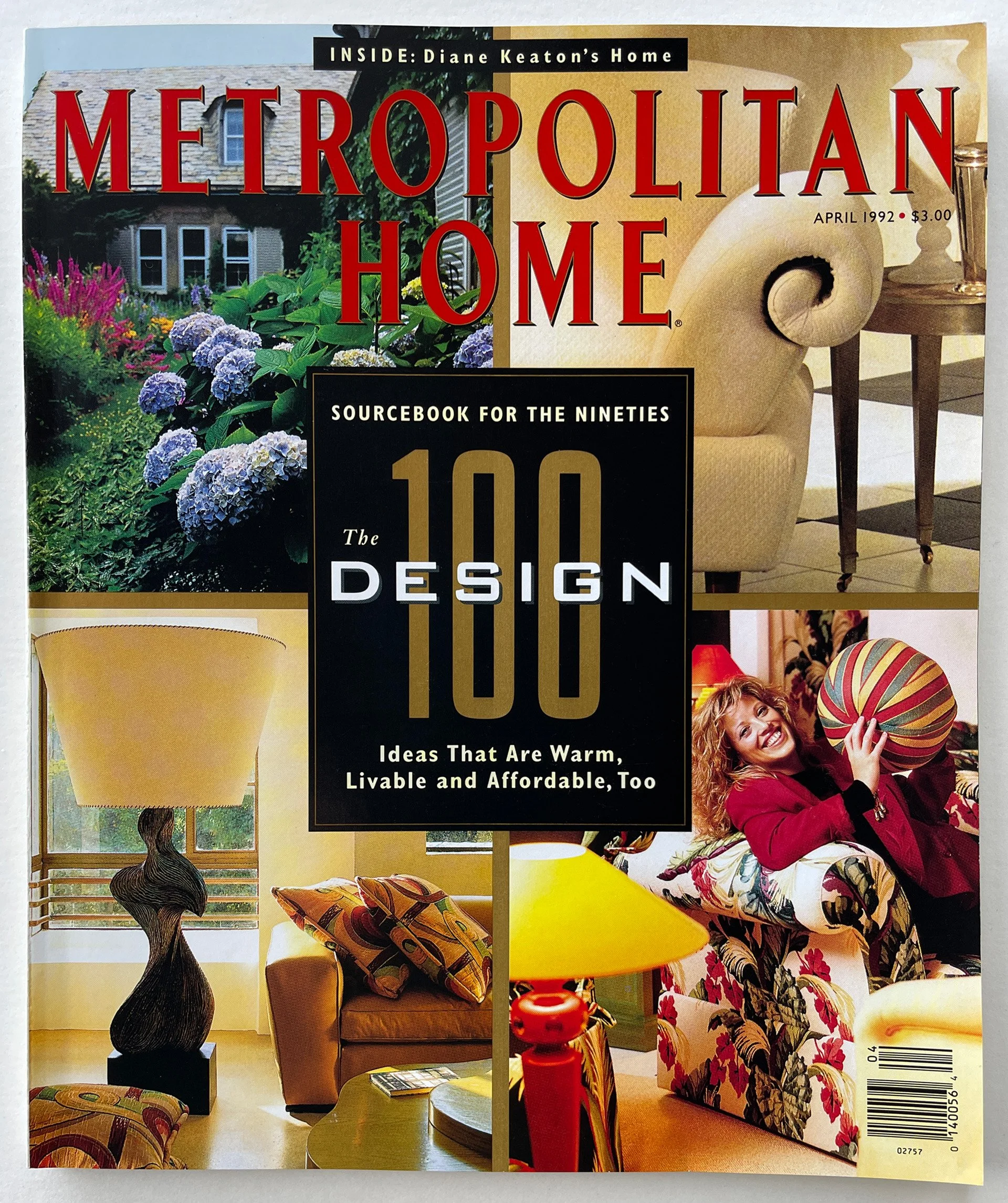

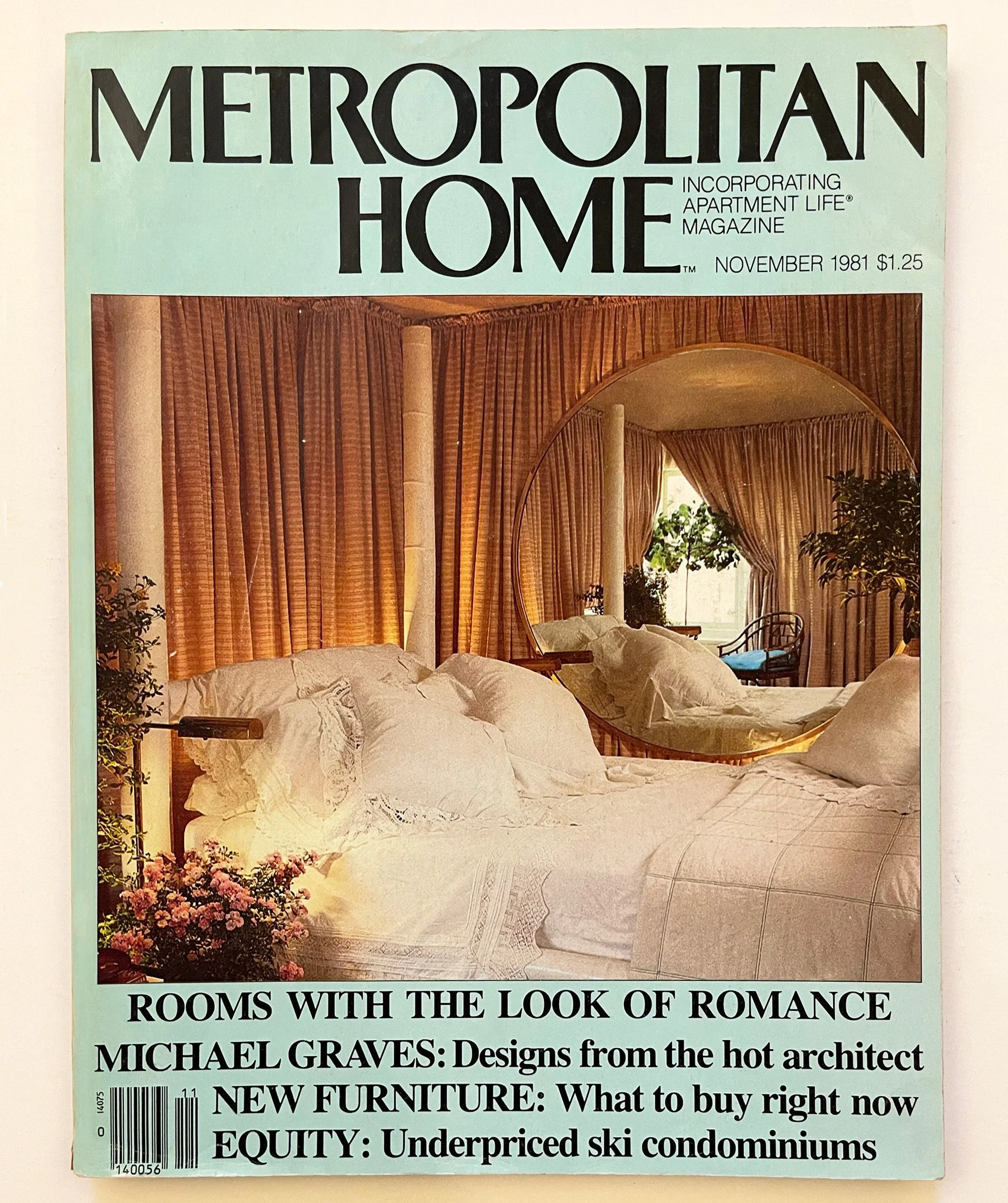

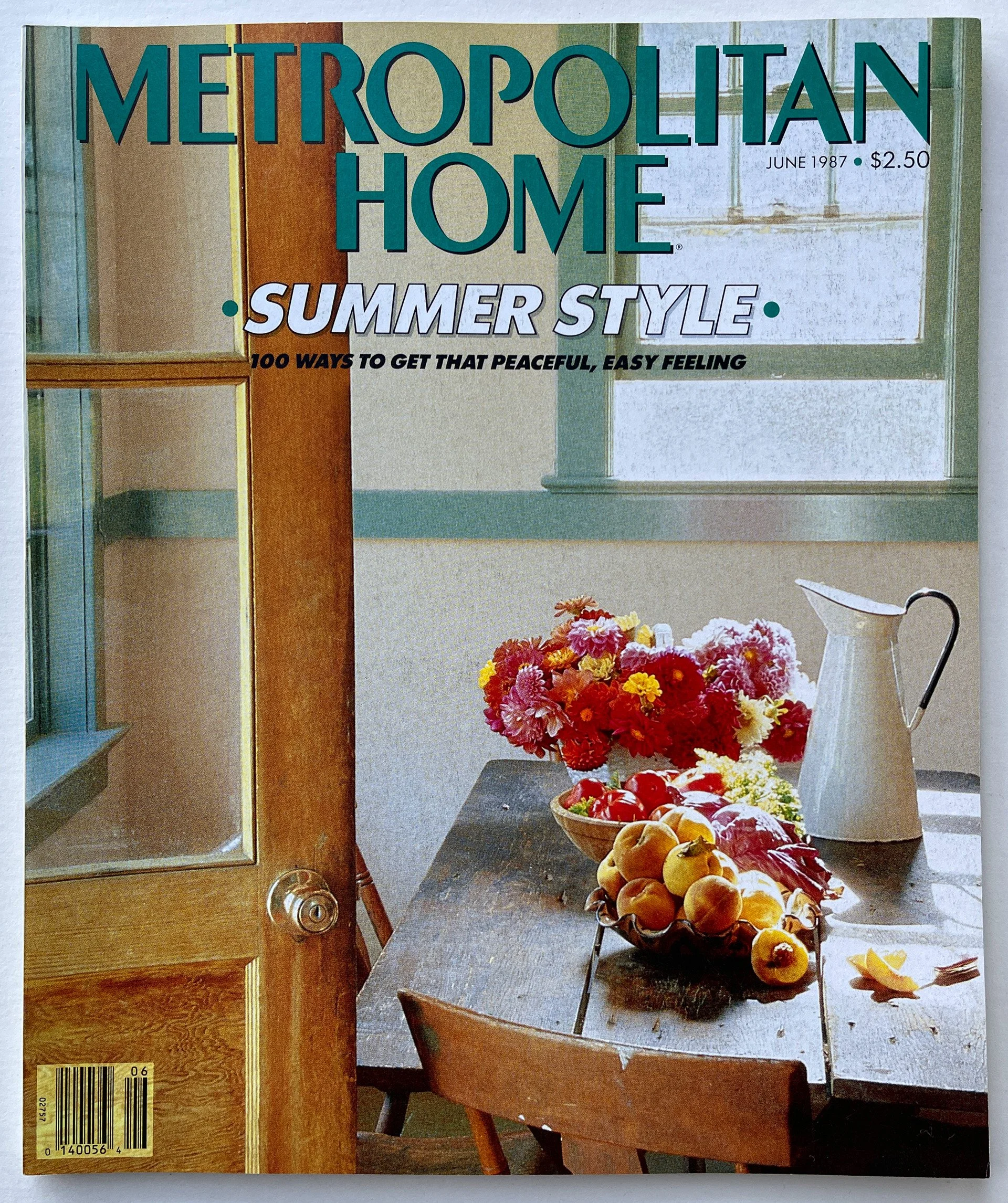

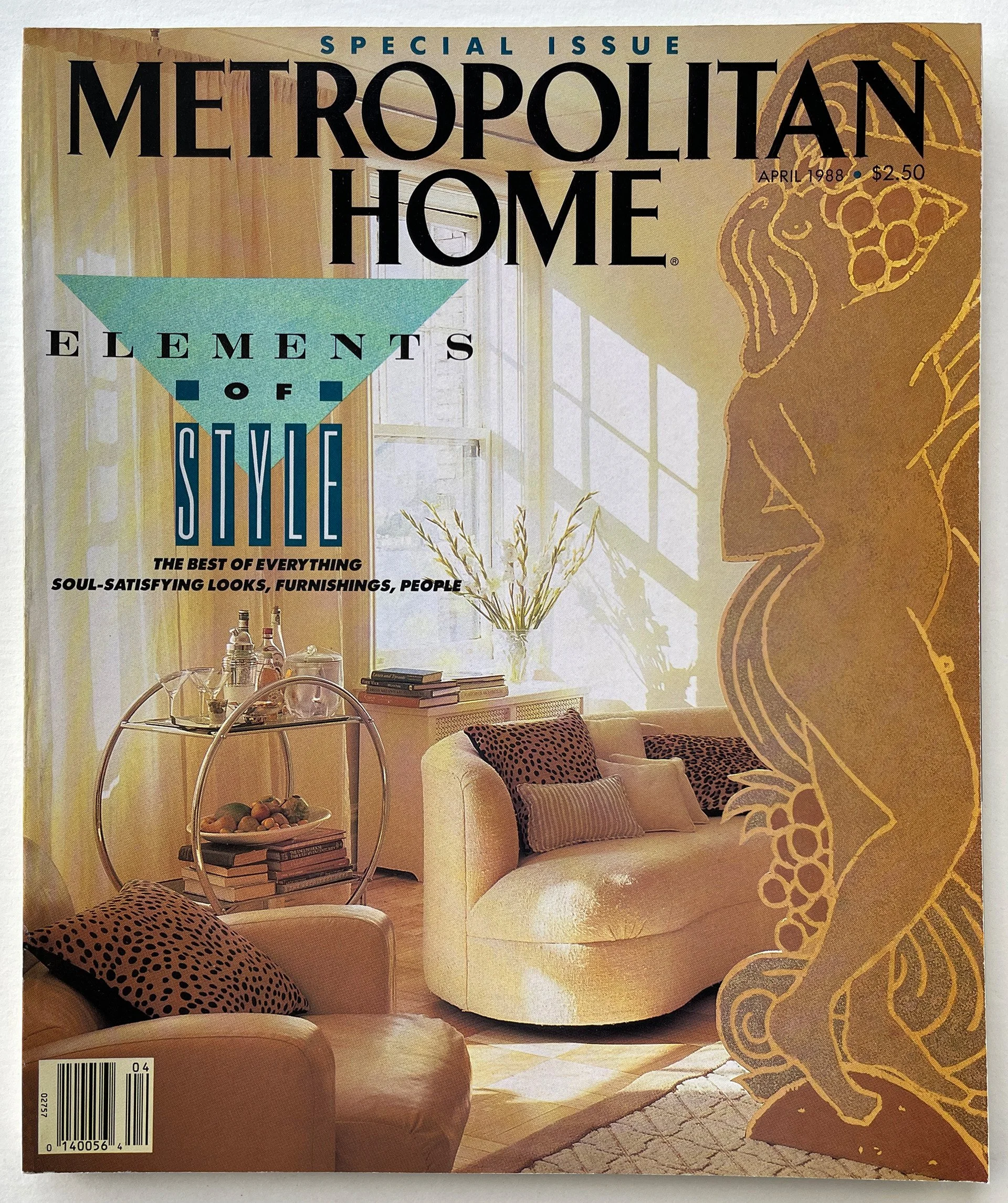

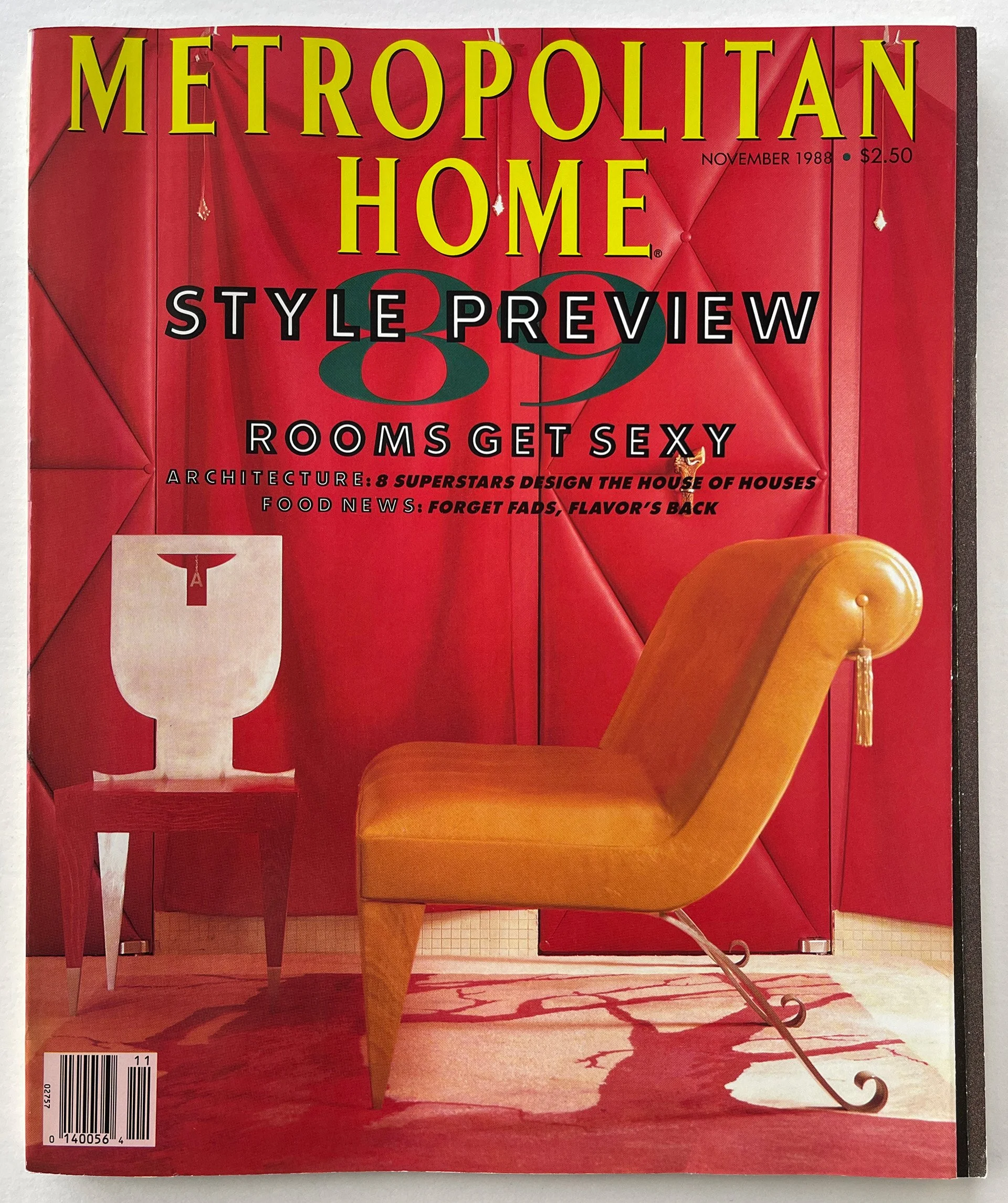

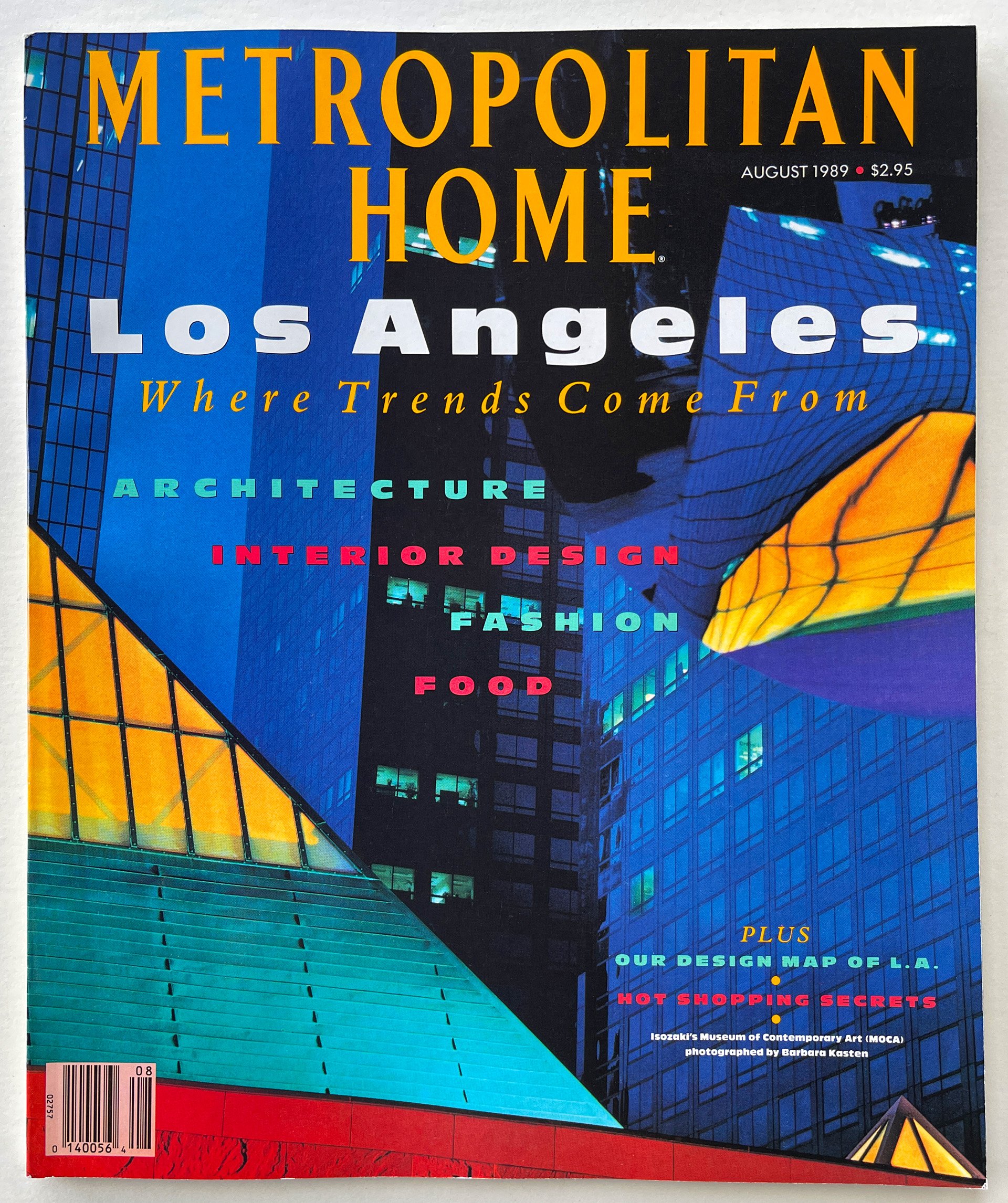

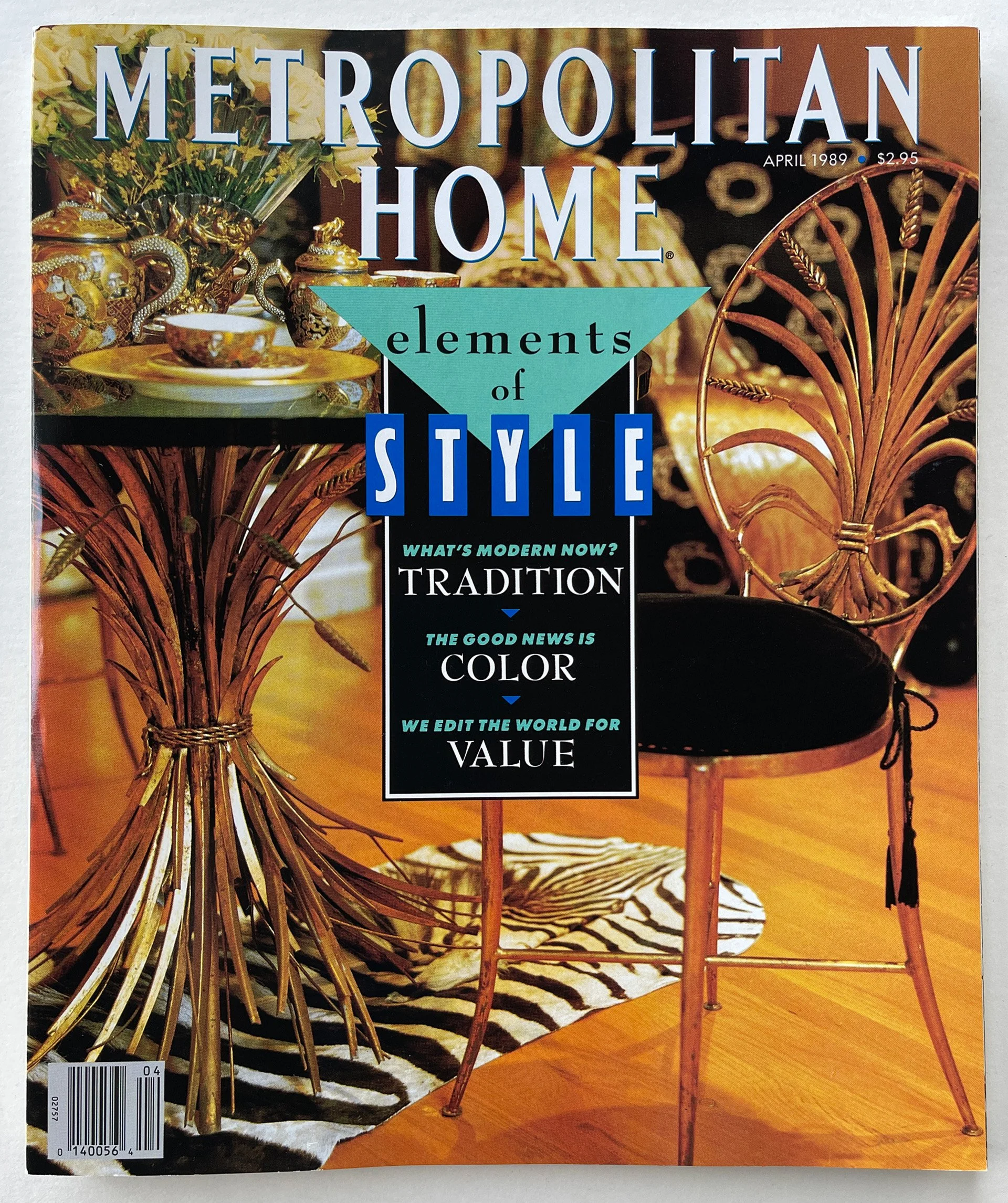

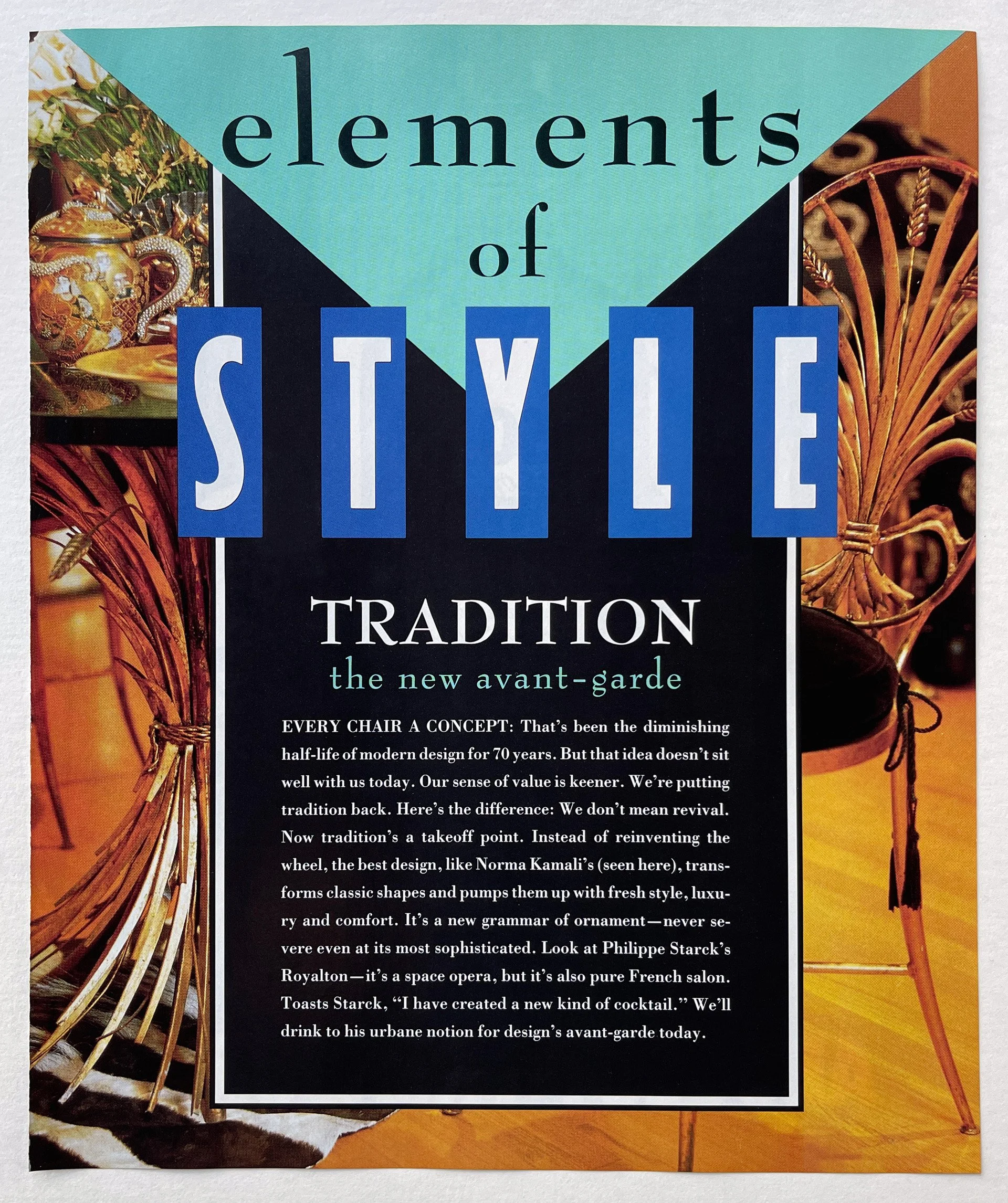

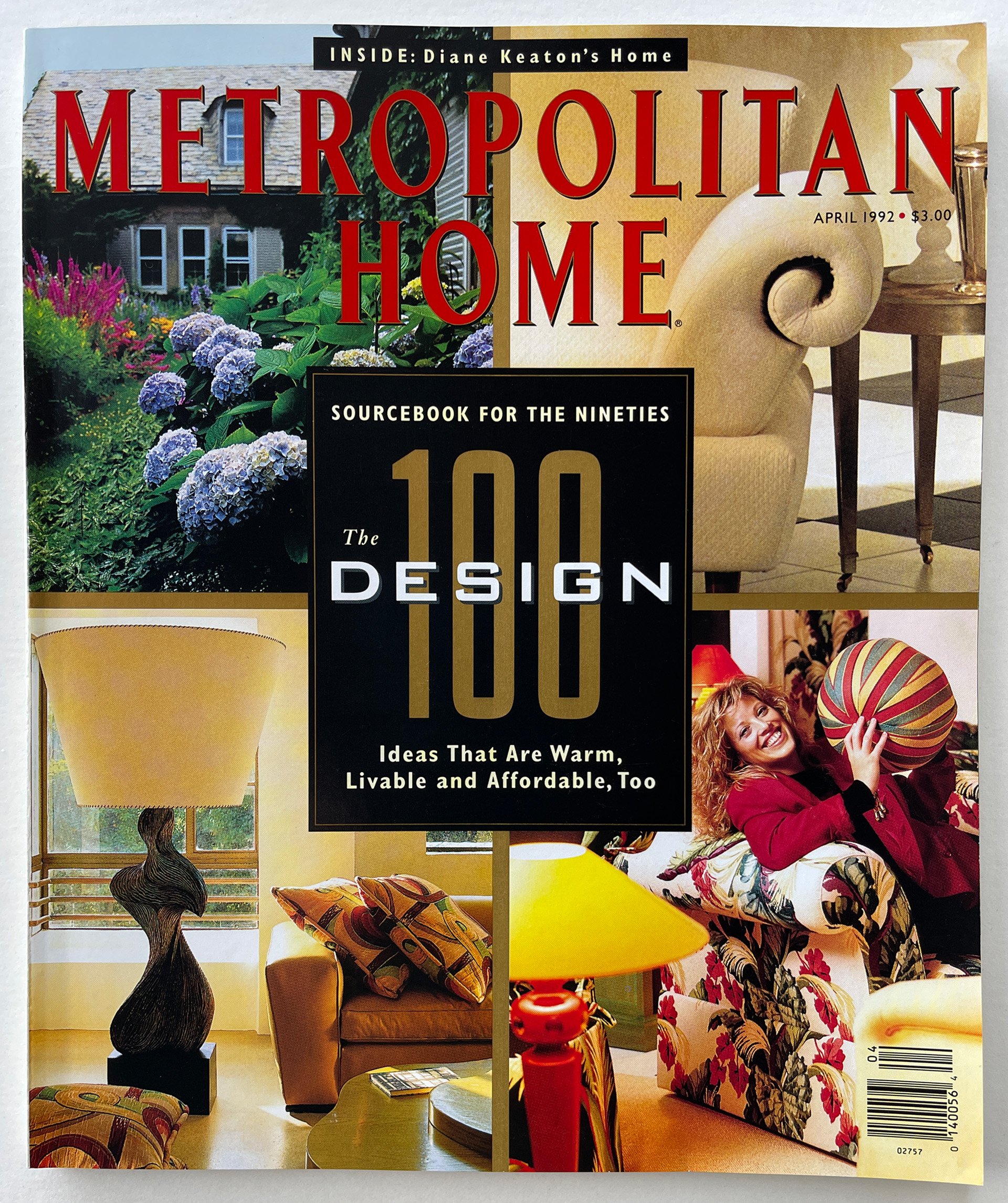

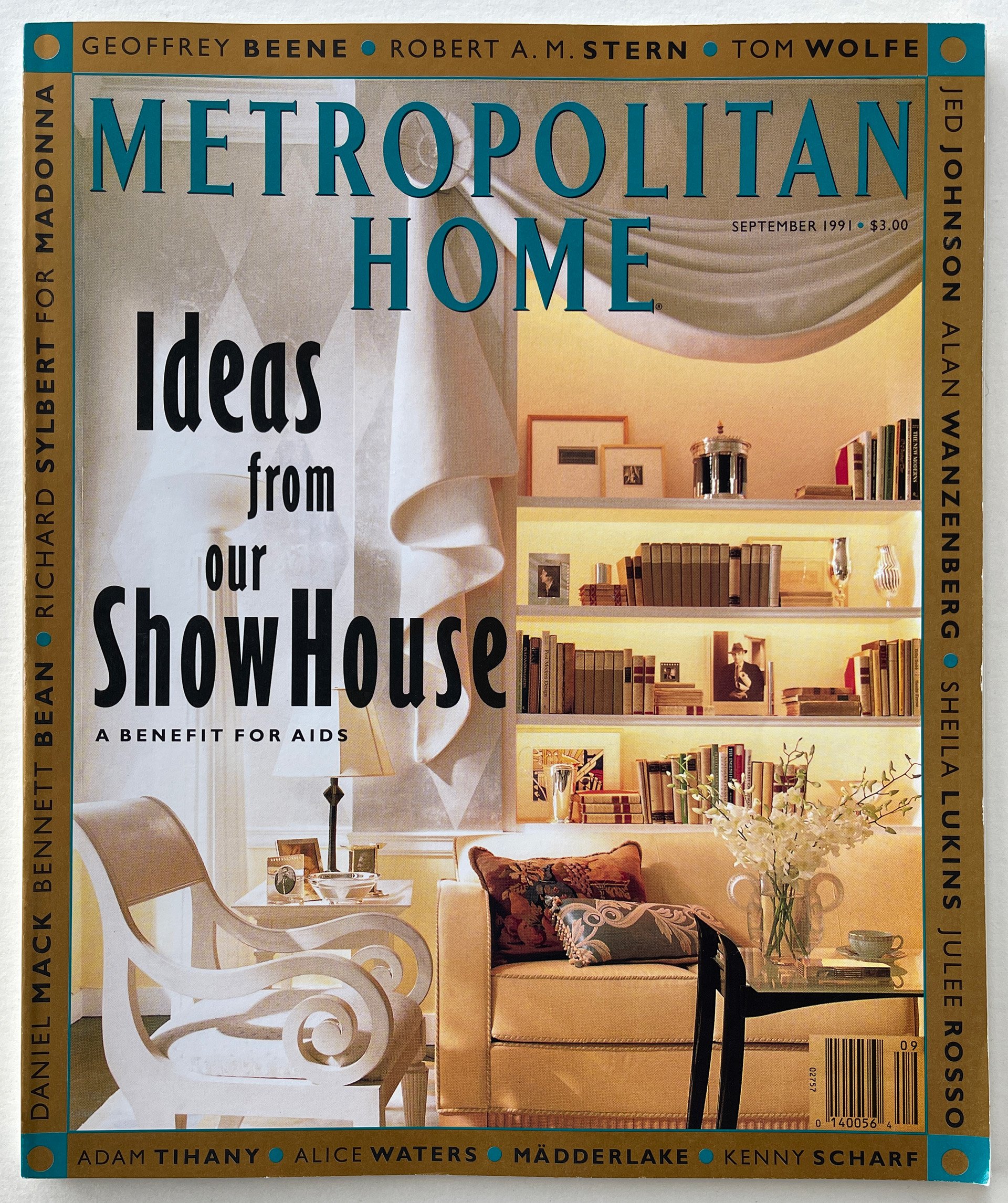

Metropolitan Home chronicled an amazing period of design innovation. Its audience was hungry for new trends, products, materials, and tips, along with inspiration for travel, collecting, and entertaining. That said, the strongest covers focused on a singular theme to make the most impactful impression on the newsstand.

“People were living very differently and their values were different. They bought different things. They wanted to design differently. They wanted to cook at home differently. They wanted to share their homes with all kinds of different people. It was not going to be the Better Homes and Gardens lifestyle.”

Dorothy Kalins (Photograph by Roger Sherman)

Don Morris (Photograph by John Dolan)

George Gendron: I want to start by asking you guys a question that Pat and I have speculated about, and we’re wondering whether it’s just our imagination or whether there’s more than some truth to this.

Not only that, something big was happening culturally in the US in the late ’70s and early ’80s. So think of this as the Apartment Life/Metropolitan Home era. And something big had to do with these really profound changes that were taking place in how, maybe baby boomers, I guess I’ll use to describe who we were at the time — still are — how baby boomers viewed their homes.

And that changed expectations, I think, about what people were looking for in a magazine. And we, being such incredible fans, in particular of Met Home, often attribute, at least some of this, to what you guys did at Metropolitan Home. Taking a completely different approach to the home as it appeared in print.

At the same time, some of the people that I grew up with at Inc. Magazine, like [Gordon] Segal at Crate & Barrel, often refer to this period, not that they had started Crate & Barrel — Segal started it in ’64 — but this was a period where, all of a sudden, Crate & Barrel started to really take off.

To the extent that I know my Pottery Barn history, the same thing was true there.

Dorothy Kalins: Yep.

George Gendron: Part of this had to do with kind of accessible housewares — really well designed maybe for the first time, but talk to us, before we get to the magazine, talk to us about what was going on in the zeitgeist that you guys were a part of and a leader of?

Dorothy Kalins: Well, to give credit where it’s due, the editors of Better Homes and Gardens and the publishers who were — Better Homes and Gardens was the biggest magazine in America and it was published out of Des Moines, Iowa — a bunch of very professional, but very conservative people were our bosses. The editor and publisher of Better Homes and Gardens kind of thought that perhaps the children of the Better Homes and Gardens readers would not be readers of BH&G.

And you’re right. It really is a baby boom idea. Our generation didn’t want to live like our parents. I mean, the fact that we have turned out to be more like our parents than not is something else altogether. But there was a huge rebellion. And we were not them.

And to their credit, they started a magazine out of the special interest division of Meredith called Apartment Ideas. They had a special interest magazine division that did things like gardening and building your patio on a weekend. And there was a whole division of special interest publications.

And so the real seeds of Met Home were in a quarterly magazine called Apartment Ideas. And the idea was that the people who were coming out of college were not going to go immediately into buying a home in the suburbs the way their parents did. They were going to experiment, they were going to travel, they were going to live in different combinations of people.

They were going to live in different ways, in different styles. Sometimes just to spite what their parents did. And they were right about that. So that magazine started sometime in the ’60s, became a quarterly, then became a monthly, and then sometime in the ’80s became Metropolitan Home. Because it really was following this generation as it came out of school, established our first apartments, our first roommates, our first relationships, and et cetera, et cetera.

Kalins had been at Apartment Life, Meredith’s youth-oriented home magazine, and later rebranded it Metropolitan Home. When Morris was hired to redesign the magazine, the first thing he tackled was the Met Home logo. Having a logo that felt cloned from The New Yorker wouldn’t do. Morris worked with noted type designer Dennis Ortiz-Lopez. The first iteration was a sans serif that balanced the letterforms and fixed the kerning. The second refined the logo and added small spiky serifs to reflect then-current architecture and interior design. And finally, the characters were made more condensed and spaced apart so the logo could mingle more with cover photography while remaining a strong statement.

George Gendron: You said when it was launched it was called Apartment Ideas?

Dorothy Kalins: Yes.

George Gendron: And when did it change its name to Apartment Life?

Dorothy Kalins: Somewhere in the late ’70s.

George Gendron: And then they recruit you, then you go to work there, right?

Dorothy Kalins: Yeah. Well, I was in New York and then, yes, I did. Then I went to work there.

Don Morris: Dorothy founded Met Home.

George Gendron: Yeah. So how did that magazine transform from Apartment Life to Met Home, and explain your role in it. Was that your idea or did they come to you?

Dorothy Kalins: They were smart enough to hire a group of social researchers called Yankelovich. It was Dan Yankelovich’s company. And they were really on the leading edge of this kind of generational surveys, studies about behavioral attitudes and buying patterns and all of that. And it became really, really clear that there was, in fact, a Baby Boom and that they were not going to behave the way their parents did.

Their values were different. Their M.O.s were different. Their living arrangements were different. And the people at Meredith that were smart enough to know that they needed a different magazine. And the reason it changed from Apartment Life to Metropolitan Home was that all the studies — there were, there are lots and lots of studies. Meredith’s a big company and there they did lots and lots of studies of their readers and of these behavioral patterns.

And it was very clear that these people were grouped around cities, the people who were attracted to Apartment Life. And they were, in fact — I mean it’s, when you look at it and you look at the map of Georgia in the recent election, it’s all those blue counties. And that’s what happens. The people came to the cities all over the country. So that’s where the Metropolitan name came from.

“I remember going around the country with the first issue of Met Home saying, ‘It’s not the Pepsi generation, it’s the Perrier generation.’”

George Gendron: And you became the editor-in-chief, the founding editor-in-chief of Met Home?

Dorothy Kalins: Mm-hmm. I was the editor of Apartment Life. Yeah.

George Gendron: So, go back to a point before you had launched that premier issue, and tell us what was the blueprint, what was the idea, what was the positioning behind this new magazine called Met Home that was growing out of Apartment Life?

Dorothy Kalins: Well, first of all, the circulation of Apartment Life, at the time we made the change, was 800,000. Which was a very, very large circulation for such a magazine.

I mean, it wasn’t the 6 million that Better Homes and Gardens was, but it was a very hefty size. The idea was — it was very much a marketing idea — to take the top, the crème de la crème, of that readership, around the most major cities, highest income, highest education, and realize that these people were living very differently and that their values were different.

They bought different things. They wanted to design differently. They wanted to cook at home differently. They wanted to share their homes with all kinds of different people. It was not going to be the Better Homes and Gardens lifestyle.

So at that point, I remember going around the country with the first issue of Met Home saying, “It’s not the Pepsi generation, it’s the San Pellegrino, or the Perrier generation.”

It was the Perrier generation. It was those subtle ideas of what we were drawn toward. And we thought we thought we were just … everything. I guess every young cohort thinks that, right? That they’re the hippest, smartest, chic-est, whatever. But basically we wanted to talk to them where they lived.

And we did not want to talk to our readers in a dictatorial way. We wanted to talk to them in a journalistic way. And that was the editorial positioning of Met Home.

George Gendron: That’s a great line. “It’s not the Pepsi generation, it’s the Pellegrino generation.” Which you could argue was a tagline for how you spent much of the rest of your professional life.

Right? Because it wasn’t just about Met Home. It was about gardening. It was about food. Cooking. So how did you and Don meet, and what was Don’s role at Met Home in these very early days?

Dorothy Kalins: Well, I’ll tell my quick version of it. At that point, I had an office in Des Moines and in New York.

I was going back and forth and we had much of the art department. There was an art department in New York, but not the definitive production of a magazine. And it was time to make the switch to be a New York-based magazine. And we had a very nice man who was an art director who wanted to go off and become a photographer again. Right? Isn’t that what happened?

Don Morris: Yes.

Dorothy Kalins: We were talking earlier about New York magazine and how all of our collective experience with New York magazine shaped us. And so it definitely was one of the first things that I did after my first job at Fairchild. But after that, I was a contributing editor at the very early New York magazine. And I got to work directly with Milton [Glaser] and Clay [Felker]. And I was really influenced by the energy, and the chutzpah, and the point of view they had. Journalism first. The look of the magazine really mattered. Every detail about it mattered. It all added up to something that nobody had really seen before.

So, fast forward, we were looking for an art director. I opened an issue of New York magazine and I saw a layout of objects. I don’t even remember whether they were chairs or gifts or whatever, but they were put on the page with such verve, and intelligence, and charm.

And our magazine covered a lot of objects, chairs, sofas, cups, saucers, pitchers, whatever. And I just wanted that energy. So I literally said to the art director who was about to become a photographer, “Find that person who did that layout.” It’s rare when you can trace it to that exact thing. But that’s what happened.

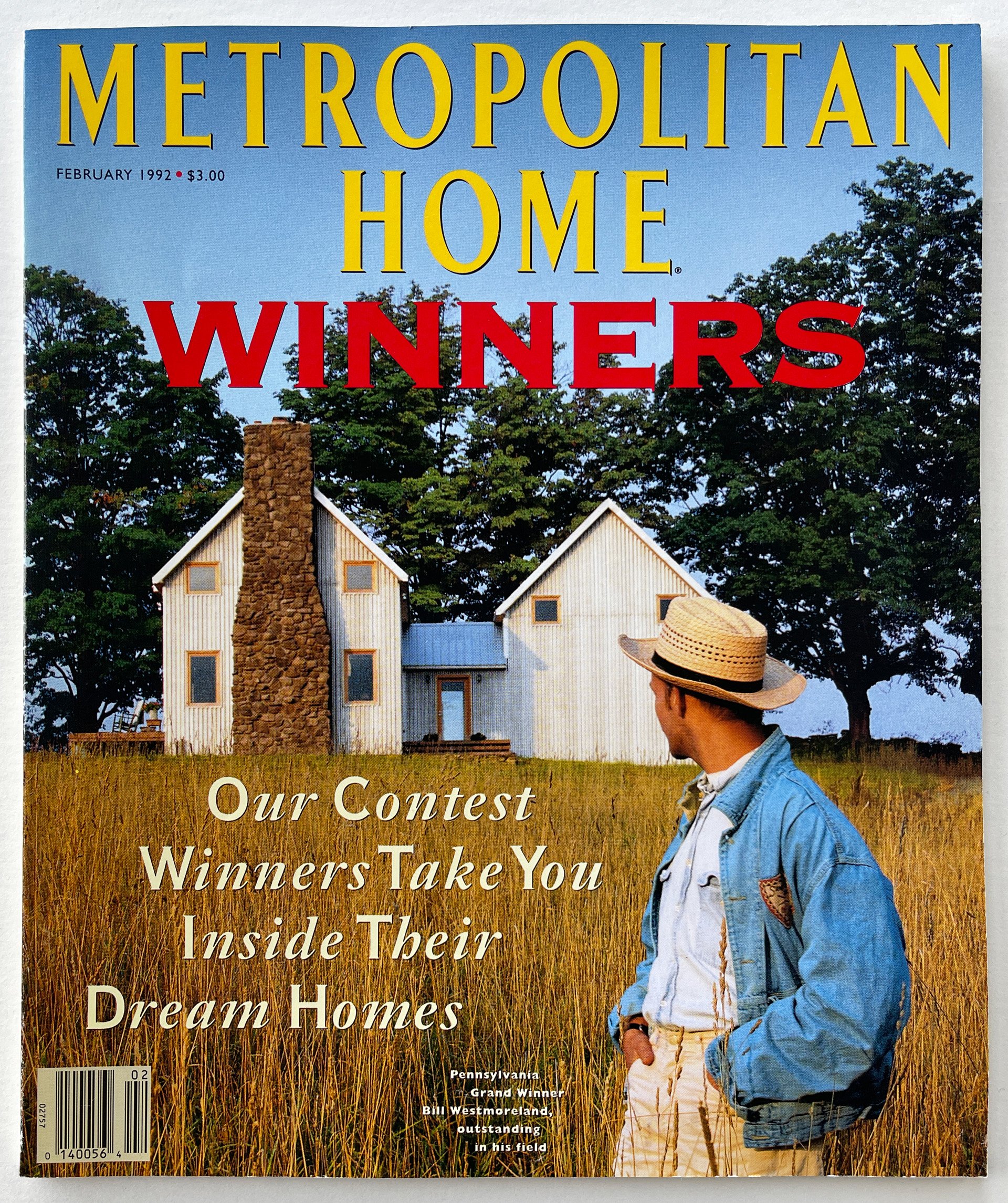

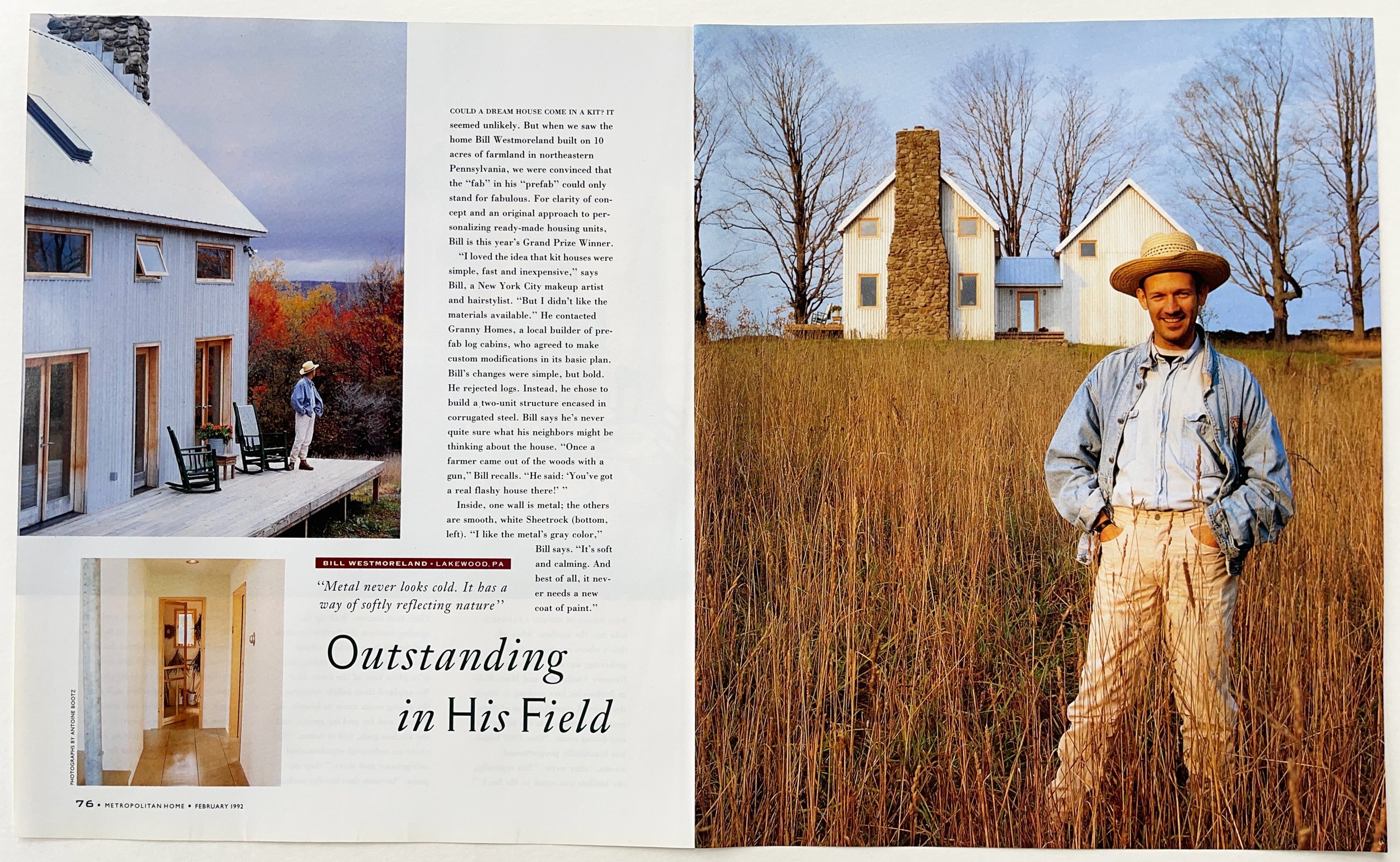

Met Home Franchise Stories

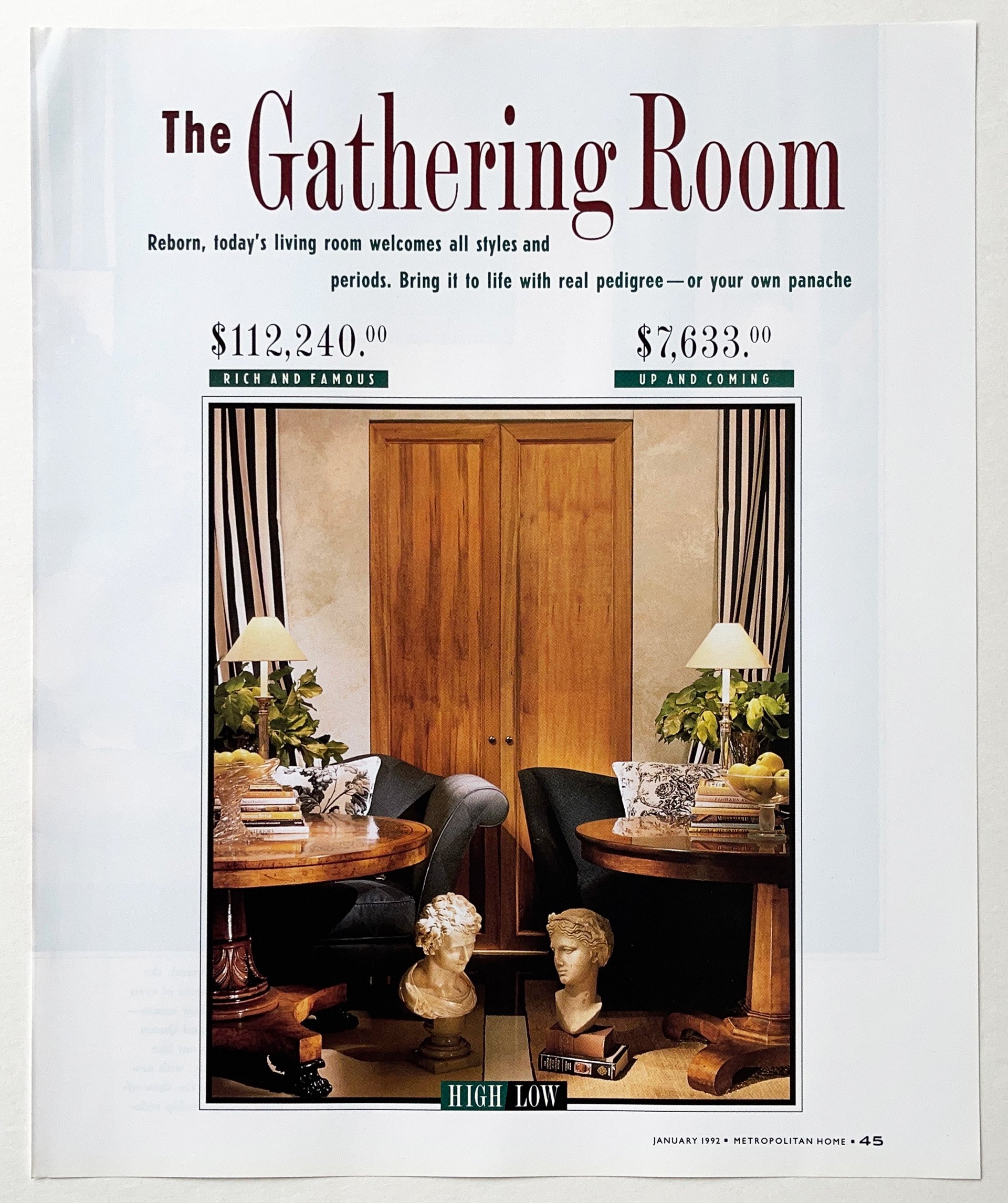

Using regular focus groups, competitions, and reader letters, Kalins identified the stories that our readership craved on a regular basis. Above, three examples: Met Home’s annual reader’s homes competition, the High/Low extravaganzas produced by Carol Helms that showed luxurious furnishings and very similar yet affordable alternatives, and inventive renovations of the ubiquitous ranch-style home.

George Gendron: And we’re assuming here that that layout was done by Don Morris.

Don Morris: Well, they couldn’t find the guy that did it. But I stepped in.

George Gendron: Nice move, man.

Don Morris: Yeah. New York magazine was just an incredible experience for me. I had just recently graduated from Parsons and a friend of mine who was working there was moving onto his illustration career and asked if I wanted to do what was the lowliest job in the art department: running the stat machine.

And it was like walking into an improvised sitcom, you know, just incredible characters, incredible energy. So many different paths crisscrossing. The non-sequiturs floating around were just so funny and so full of smart minds that I was just taken. I always thought I’d be there for about two weeks.

Dorothy Kalins: It was never a division. Something that you and I always maintained. There was never a division between words and pictures. Never. It was always the pages. It was always the message. It’s how you got the energy out to the reader.

George Gendron: When we were talking a few days ago I was mentioning my time there as a very young kid and that was my first job. And so I grew up, unfortunately, with the expectation and understanding that, “Well, that’s the way all magazines worked.” You know, that’s the way all editors and designers collaborate. And then I left New York and found out...

Don Morris: So Roger Black had just taken over at the time at New York and I’m running the stat machine, and thinking that I was only going to be there for a little while. I was always asking questions and seeing if anybody needed anything, and I just couldn’t believe I was there.

I was so excited about being there that I think I had this smile plastered on my face the whole time. And about four months in, Roger Black came in and — he moved through the art department like the furniture was going to stop him. It was just like this force going through and talking as he went.

And always very entertaining. And he asked me if I wanted to go out to lunch with him. I went out for my first business lunch, had my first sushi. And he’s telling these amazing stories and at the end of the lunch he said, you know, “I love your enthusiasm. I love that you have an interest in all this. You have great ideas. I’m going to make you assistant art director.” So I came back ...

Dorothy Kalins: …Had you done layouts before?

Don Morris: No. No.

Dorothy Kalins: “You’re a nice guy. You’re adorable. I’m making assistant art director.” [laughs]

Don Morris: You know, yeah. It was sort of shocking.

George Gendron: What did he see in you?

Dorothy Kalins: Smartest thing he ever did!

Don Morris: I don’t know. You know, I was really struck from the beginning with the generosity that a lot of people in magazines had. You know, before that ever happened, just the way that people would explain to me what’s going on and exposed me to things.

And then after that, the four people I was in charge of had to teach me how to do the job. So it was my first challenge of management. But luckily I had such nice rapport with them and they were such nice people that they helped me along. So I learned a lot. And when Roger left, Robert Best took over.

Patricia Bradbury was his art director. And Bob was just a force of energy and goodwill. And he did a lot of things — at the time, Ed Kosner became the editor and wanted to put a stop on anything that was too experimental. He wanted to make basically Newsweek for New York and bring credibility into a magazine that was known for being very fluffy.

And, at a certain point, we were doing layouts twice. We would do Ed’s version and we would do Bob’s version on a weekly basis to try to get ideas across. And we did this for months. And for me it was an incredible opportunity because I was in charge of the more formatted thing. So I learned really how to do layouts in a pretty executed way while Patricia and Bob would experiment and go off and do these amazing things. And then I would draw little dingbats or little drawings for the things that Bob was doing. And, at a certain point, there was this incredible moment where you would meet with Ed and he would talk about the stories and he started to draw on a pad ideas that we had shown him in layouts that were rejected.

So Bob’s tenacity — and you know, he didn’t change. He just moved through things. He was someone who saw the long path during a weekly deadline. And from that moment on, we got to do all these different things and Ed trusted us.

And so when Mike Jensen, the art director, came to me — I think I had been there for four years — we had won the National Magazine Award for design. It was just thrilling. And I was ready. I had done a lot of studying. I was working on a lot of freelance on weekends.

I was really trying to really get to know this as well as I could, spending a lot of time at newsstands. And I became really enamored with the Esquire that Robert Priest and April Silver and Stephen Doyle were doing. It just was, I thought, an incredible, urbane, bold execution of a magazine.

And as I read it, it really brought me in. And as I became an avid reader, I saw how well it articulated the voice of the magazine. So that was a completely different thing than New York, which kind of changed its hats every week, doing radically different editorial requiring radically different solutions.

So when Mike Jensen came to me I was really intrigued with the idea of taking a magazine and really trying to find its personality and find its voice. And when I met with the staff, it was this incredibly exuberant staff at Met Home who really knew the subject and were incredibly enthusiastic and knowledgeable about it.And I didn’t feel like that was on the pages.

So I left the interviews thinking, “This is an incredible opportunity because I think I can make a magazine that looks the way I hear these people exploring and speaking about the subject matter.” So it was just a great moment for me to move on to something that was a whole different kind of way to think about design.

“For Dorothy to say to me that she liked what I was doing and felt like it was making some change to something that she held so dearly was an incredible thing.”

George Gendron: I want to put the Met Home story itself on pause for just one moment and comment that we’re talking about 30 years ago. And fast forward, and you two, editor and designer, are still working together 30 years later. I think that’s probably more challenging and difficult than sustaining a marriage for 30 years!

Don Morris: Yeah. Well, you know, we considered marriage, but we thought this would be better.

Dorothy Kalins: Yeah. Way better!

George Gendron: Very smart. So what’s the secret sauce to having this kind of vibrant, intense, collaborative relationship that lasts not for a period at a publication, but for decades over a wide variety of different projects?

Dorothy Kalins: I think it's mutual respect and we love the work. We love the work. Yesterday we were on the phone for five hours just laying out one chapter of a book we’re doing, and it’s a constant conversation. The conversation is probably the same conversation we’ve had for many, many decades. But it’s always about how to get the ideas across. It’s never about decoration.

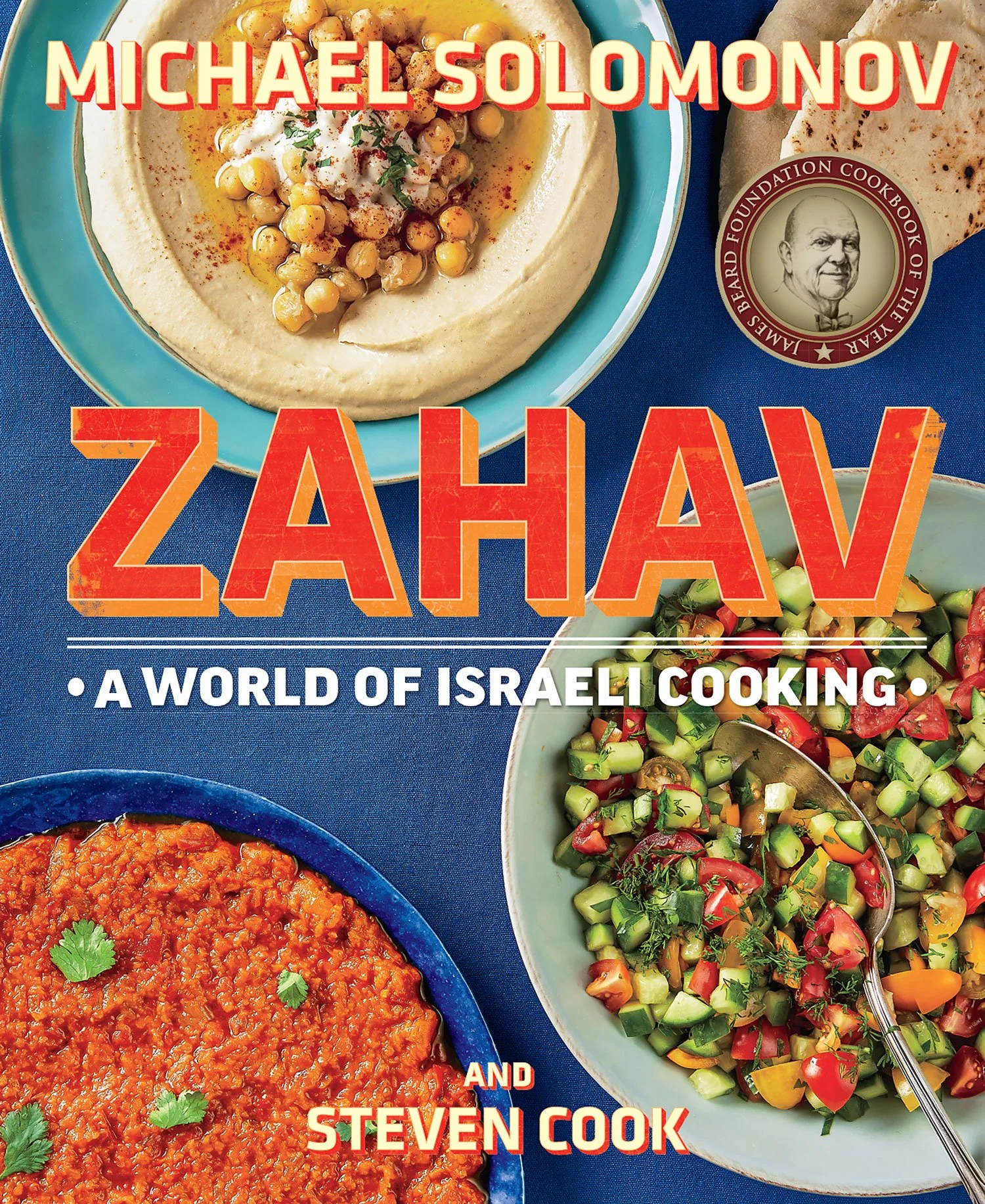

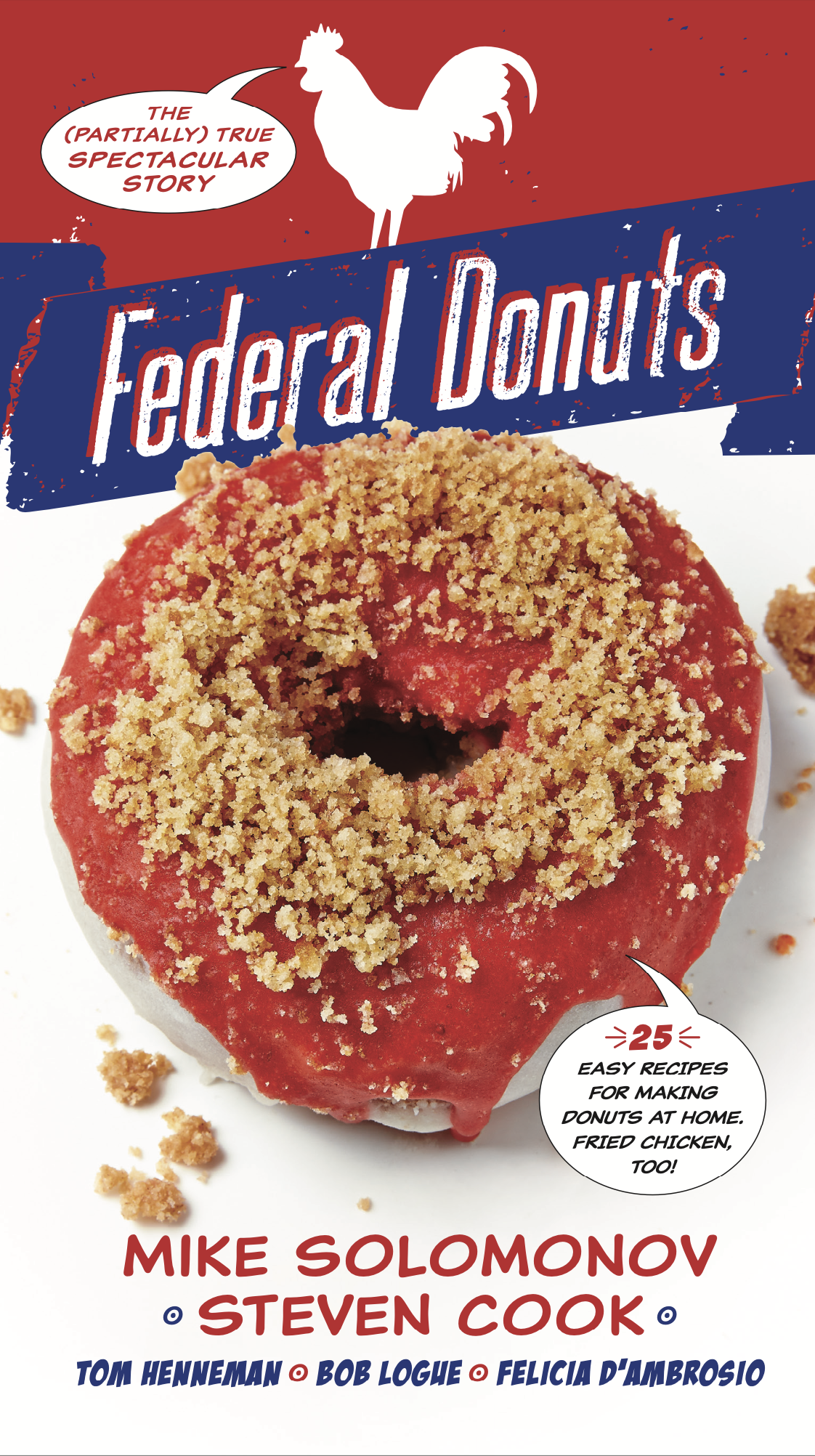

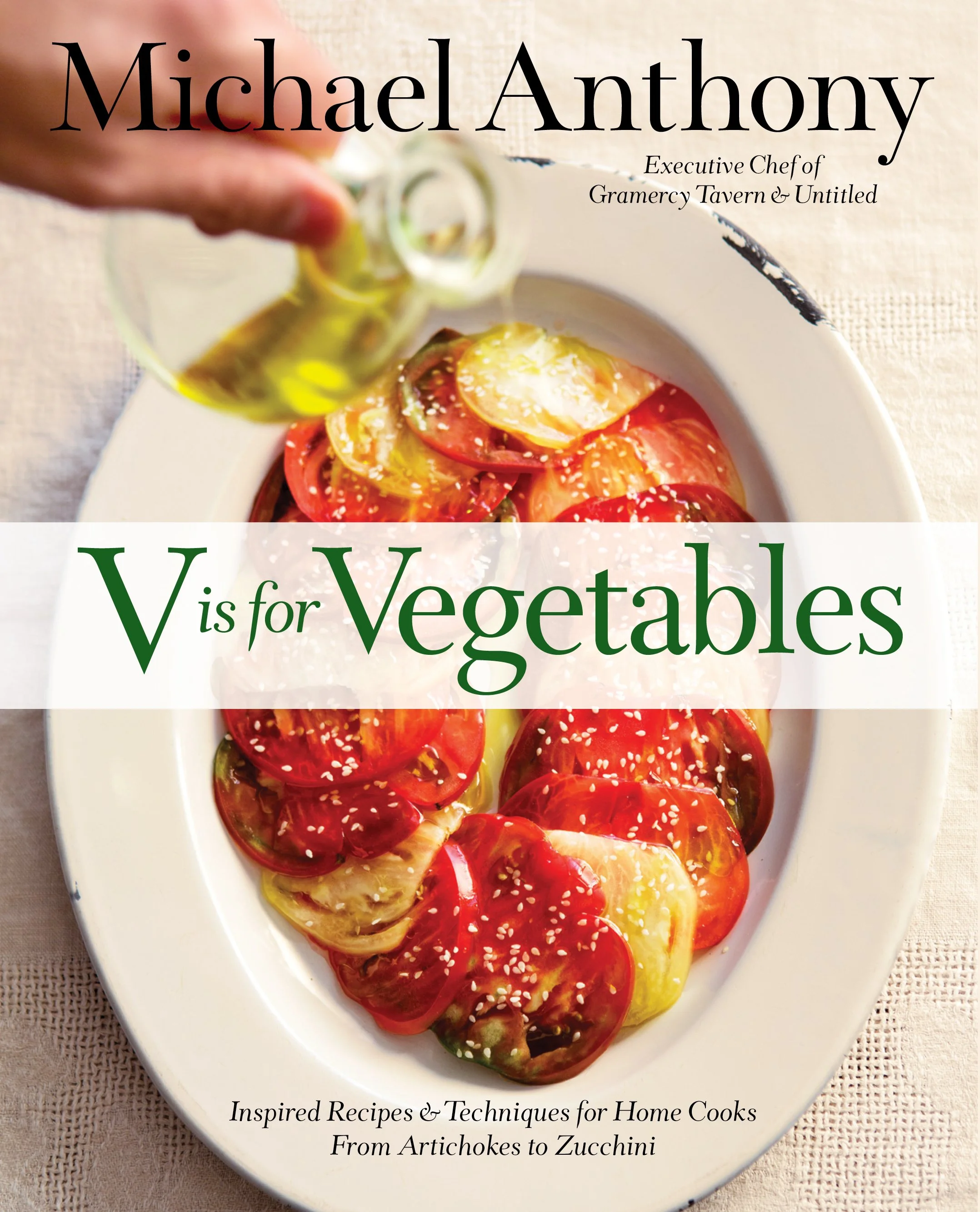

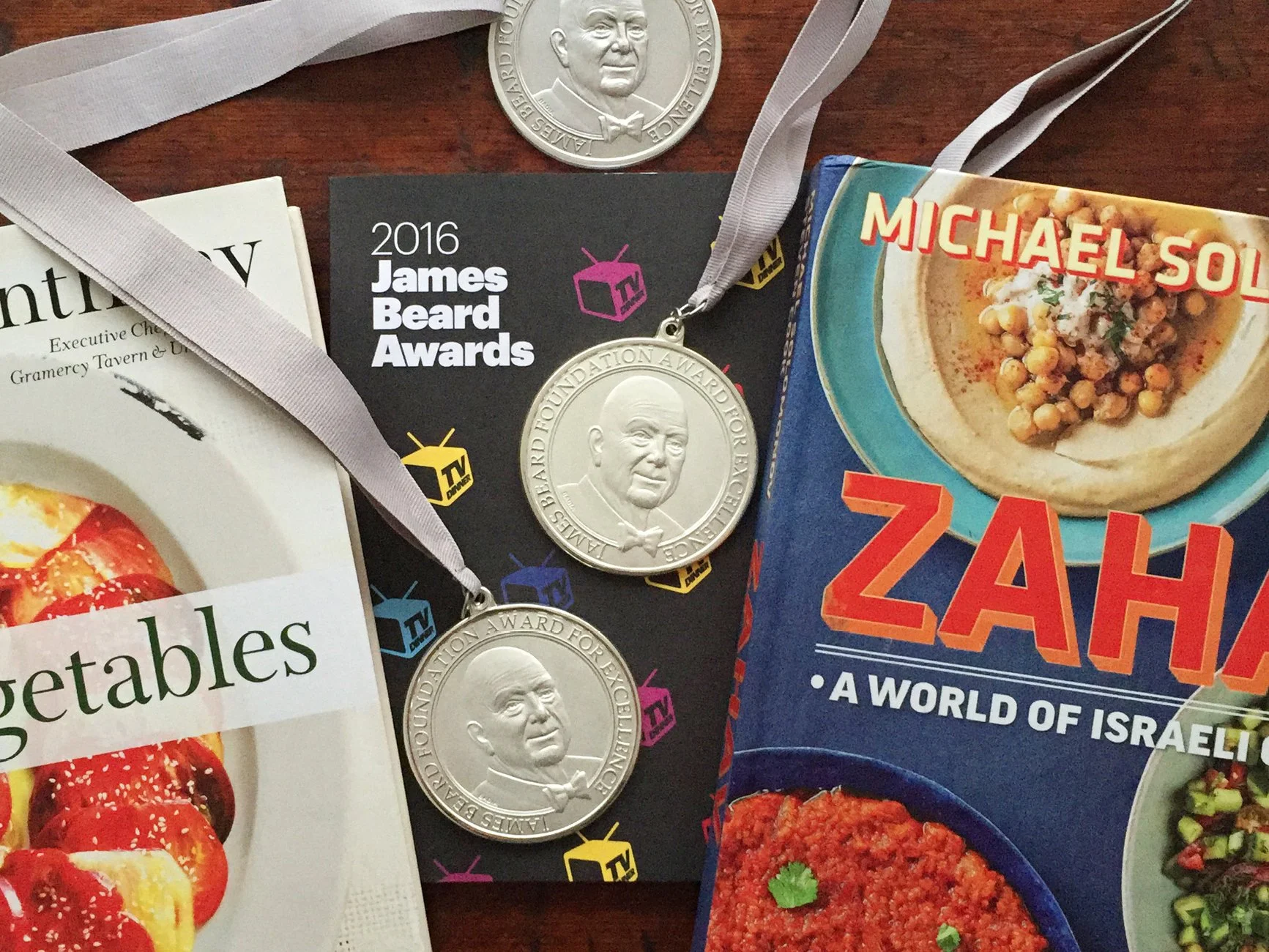

It comes from an intrinsic love of the subject matter and then, you know, a very eager way to interpret the way it goes. I mean, when I started doing books after a long, long career in magazines, it was never a question to me. And Don had his own studio by that time and — we’re skipping ahead decades — but we just started doing from day one, my first book, I knew.

See, there’s a little subversiveness here. It’s not just ego. I just knew that we know how to tell stories. And when I started doing books after I left my last magazine job, I thought, “Books are so stupid.” They’re done by 16 different people who are not talking to each other. You have the person who’s the writer, then you have the person who’s the photographer, and then you have the person who’s the designer, and then you have the person who’s the production manager. And nobody makes something that’s a whole. And I said to myself, “If I’m really lucky, I’ll be able to do books the way we’ve done magazines.” Which is a totally collaborative way.

So on every book we’ve ever produced, we’ve had an agreement — and we are lucky enough to have found a good agent who was able to sell this — that we deliver finished files. Just like a magazine goes off to the printer, our book is finished. Now, fortunately, we rely on a copy editor at the publisher and, believe me, I love copy editors, and publishers do certainly add value. They get the right paper and they make sure the binding is right and they produce the cover, and they sell it. Maybe. Sometimes. But we really do books the way we’ve done magazines.

George Gendron: Okay. Don, what’s your version of that relationship?

Don Morris: Well, to go back to the beginning when I was hired to redesign the magazine, that was always kind of part of the brief. And so that meant that I could begin experimenting and begin talking with the staff and looking at the competition, looking at what we wanted to do.

And four months later — Met Home had great parties, you know, everybody, there was a great cook. They knew entertaining. We talked about entertaining. And they had the best parties. And, maybe four months in, there was this party at someone’s townhouse — I think Ben Lloyd’s townhouse in Brooklyn — and we all got out there and, you know, there’s fabulous music, great food. We’re having this great time and just hanging out together and laughing. And Dorothy pulled me aside and said, “You’ve already made a tremendous change. I’m so excited about what you’re doing.” And that was incredible. It was incredible to have that kind of support.

The Met Home Mix Tape: Art department tunes, circa 1986–92, courtesy of Don Morris.

And Dorothy had a very journalistic approach to design. So she really understood it. She really understood what was going on at the time — who was making waves, who were the people that were doing work that really lasted over a period of time. And for her to say to me that she liked what I was doing and felt like it was making some change to something that she held so dearly was this incredible thing.

So from the beginning, I had a lot of support. And that also meant that I had to go through a gauntlet because the magazine was filled with design people. Journalists as well as people that built sets. That thought of really incredible solutions to ways to live. And they would build things.

And we would put all the layouts on the wall and everyone was invited to comment. So it was rigorous, but it was also smart people talking about what you do. So I had to defend things. I had to learn things. The whole experience was really like going to grad school.

We had a network of writers and editors around the country that we called city editors and they would report on what was going on in their part of the world, part of the country, trying to pitch stories. So it was competitive and they would come in a couple of times a year, they were constantly feeding new ideas.

So as a young designer, I was hearing about all the stuff that was going on all around the country. Seeing images of it, hearing about what was moving, what was shaking, what was working, what wasn’t in retail, in design, in architecture. It was incredible. So I would go back and I’d talk to the people in my art department at certain points, the people that were higher in the art department would also attend these meetings.

It was all about learning and reflecting on what was going on, and trying to figure out how the magazine would, again, get that voice and get that sort of framework that would really be in sync. This pretty incredible moment with a lot of design exploration was happening in the country, but also in the world. We did a lot of things in Europe. We started to look at Japan. There was a lot of really interesting information that was always passing through the doors. And that was great for us to be influenced by.

George Gendron: Don, you mentioned the network and I’m curious about that perhaps because I was myself in New York and a New Yorker, and I was an avid reader of Apartment Life. I always thought of it as very New York-centric. And maybe it wasn’t.

Dorothy Kalins: It was Des Moines, Iowa-centric at that time, early on!

George Gendron: Well, you fooled me, I gotta tell you. And so I’m curious about this idea, Dorothy, about having this national network of contributors.

Dorothy Kalins: We always believe that ideas come from all over, and it was never a top-down dictatorship. I never believed that. I always believed that you get the smart people in a room and the best ideas happen, they “verbal up.” And that’s my little parenthetical about people who are now working remotely. I mean, we managed to have a conversation right now, with us, because we share a frame of reference.

But think about the young people. Where do they learn? They don’t learn sitting at their computers and then going off and watching television at night. You learn by being, by experiencing, by traveling, by talking, by all being in the room together. And I just believe there’s a certain chutzpah that happens when the people are in a room together and you get the right people.

And I always gravitated toward people — not Don, because Don was demonstrably excellent in everything that he did — but some of the design editors that I hired were not people who came from House Beautiful. They didn’t come from Architectural Digest. They came from life.

One worked with Terence Conran at Habitat in London. One was an Italian American who grew up in Italy and just happened to have the right fingertips to everything. One was a woman who had worked at Better Homes and Gardens, so she had the grounding on that. But she was frustrated because she couldn’t do enough. So it was always “get the people in the room.” And it’s all the people.

Not only were there no walls between the art department and the editorial department, there were no walls between the kids we hired — really smart assistants who all came out of good educations and learned everything and they were hired up and they became editors themselves. So it’s about the ideas. And it’s about the energy. That’s what magazines at their best are.

You know, I’ve taught for years and years and years, both at the Stanford Publishing Course and at Yale, and I hear what people do at other magazines, which is, “You have to submit an idea in writing.” Well, if you submit an idea in writing, you’ve already sucked the air out of it and you don’t have that buy-in.

What happens when people are really enthusiastic about being in a room together and they make it better. They just nudge it a different way. And they feel a part of it. So that’s how we built our staff and that’s how we operated.

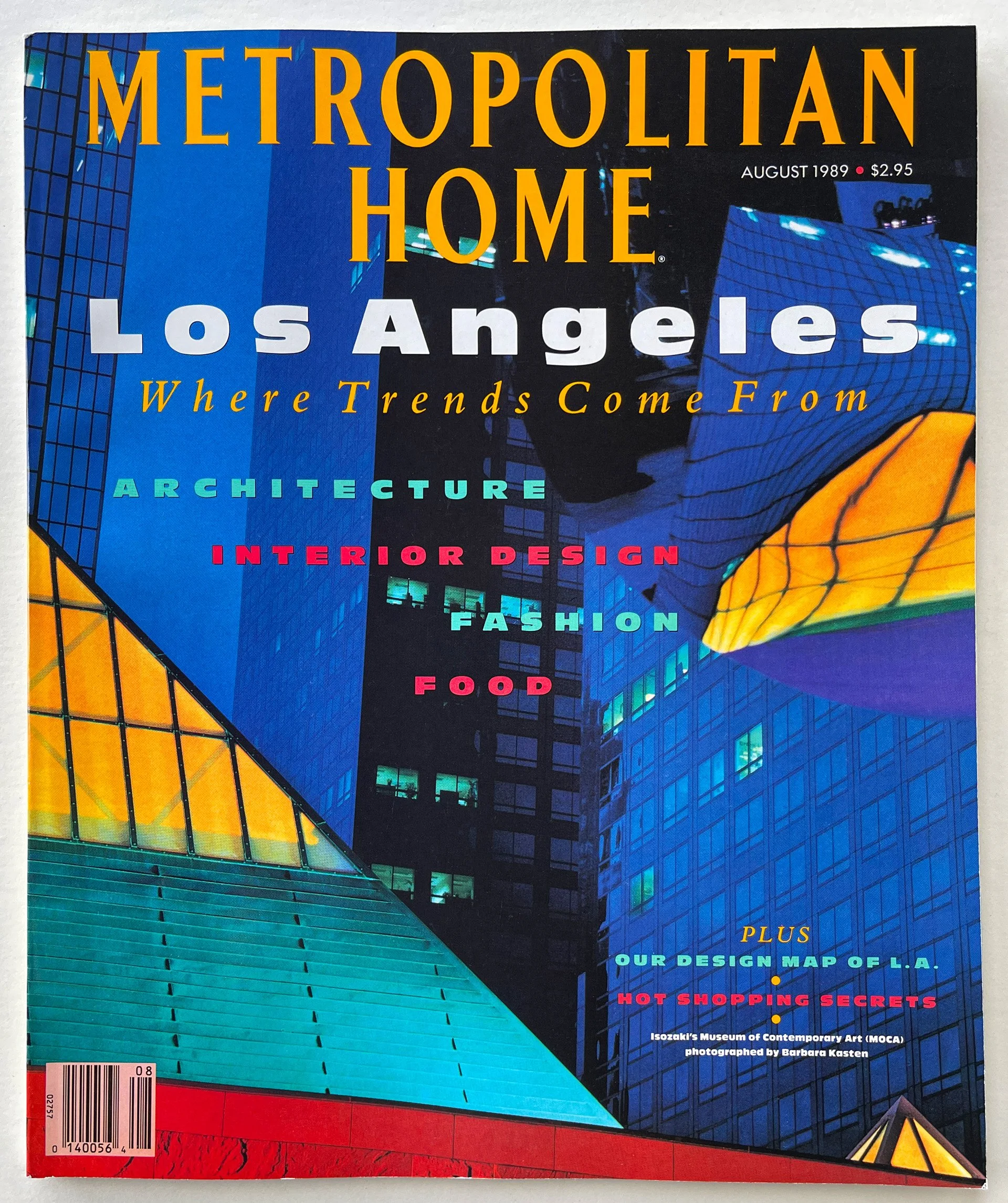

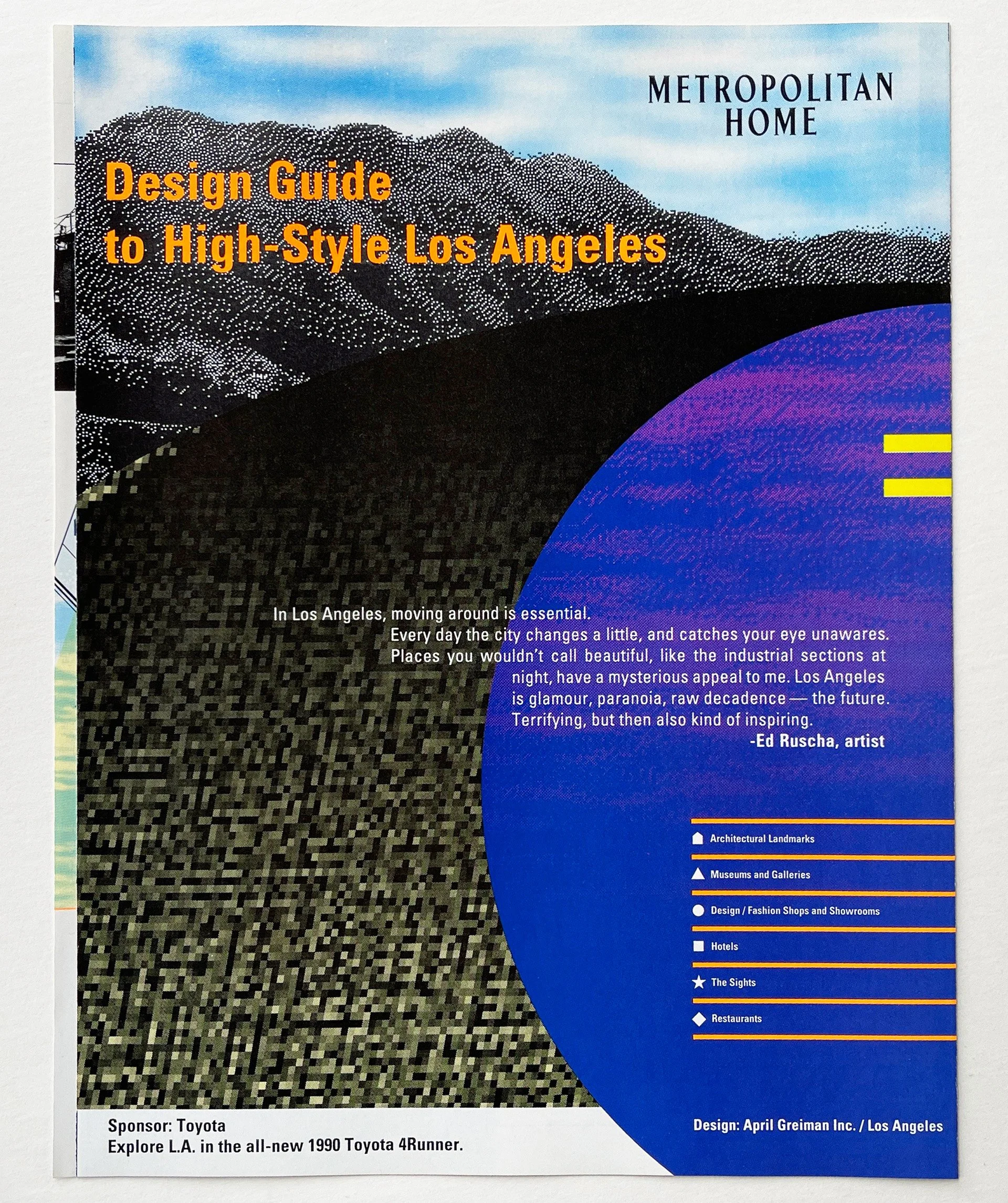

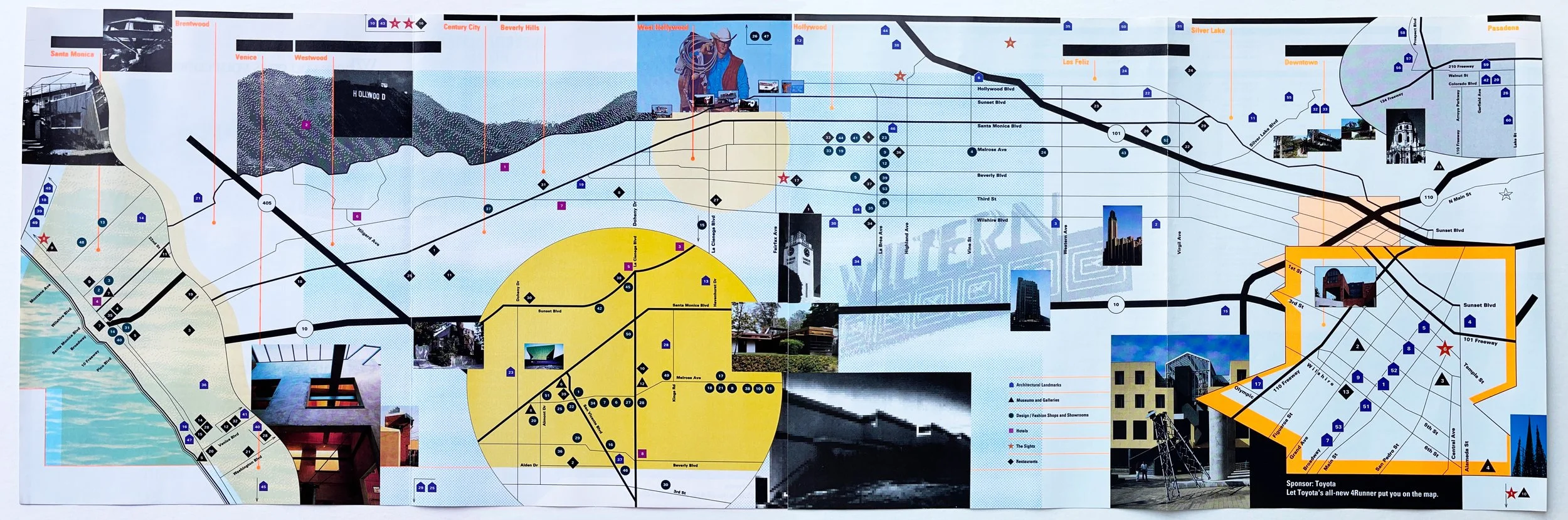

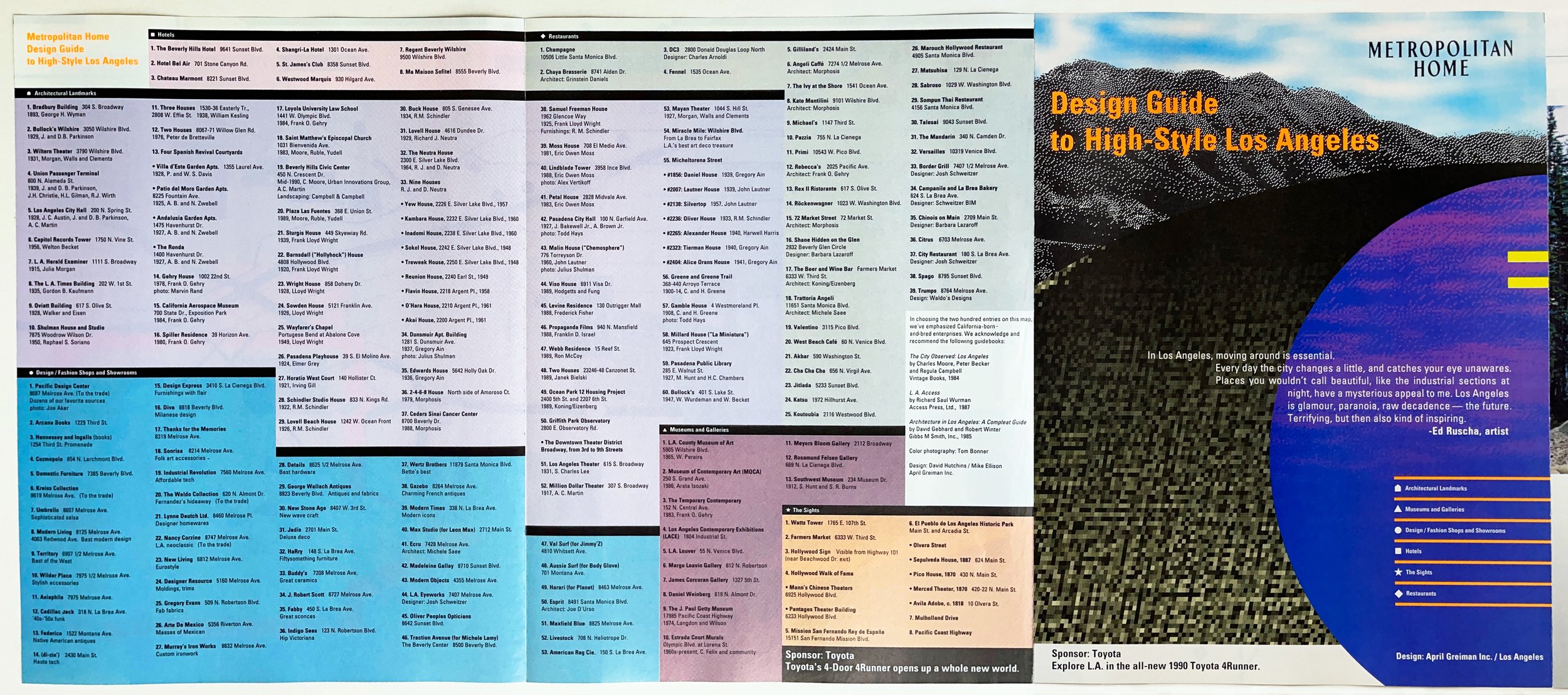

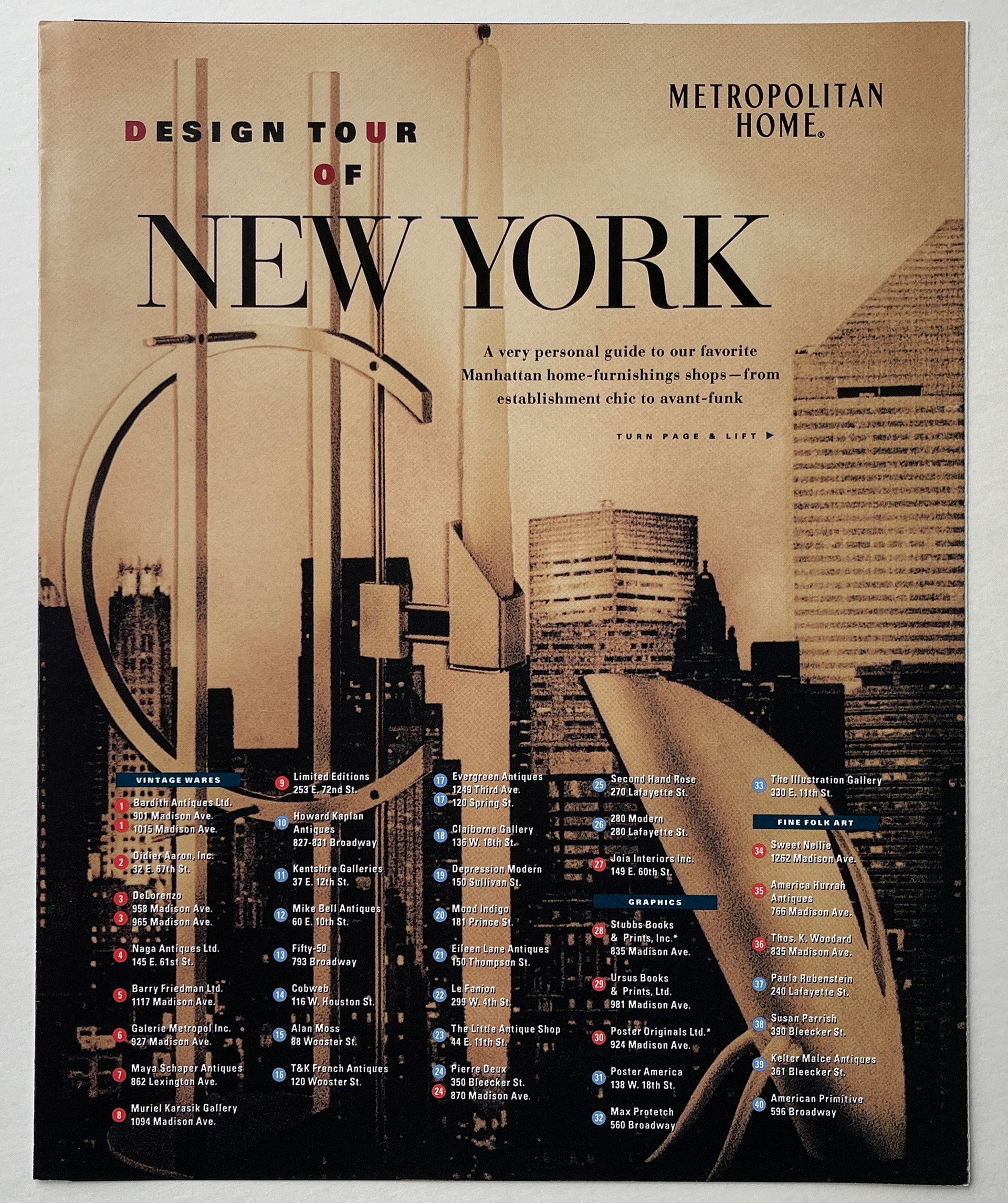

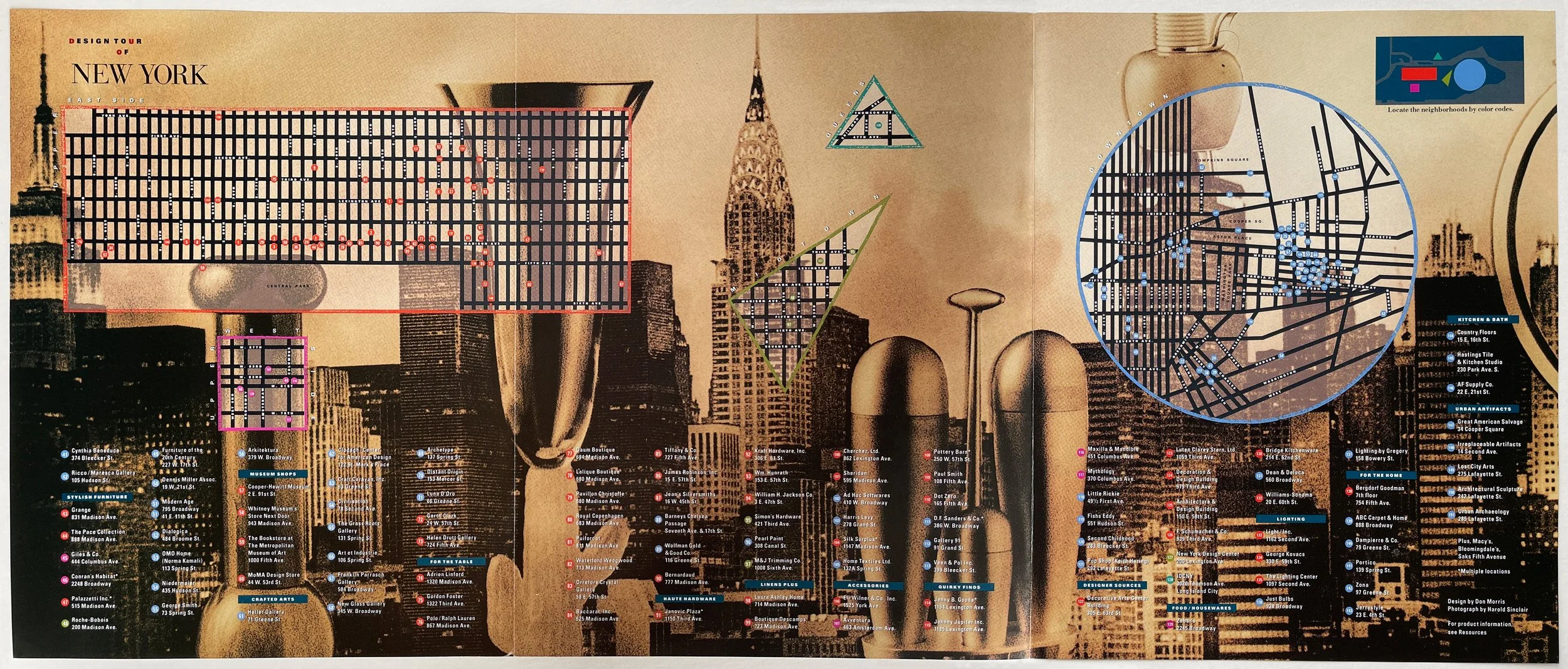

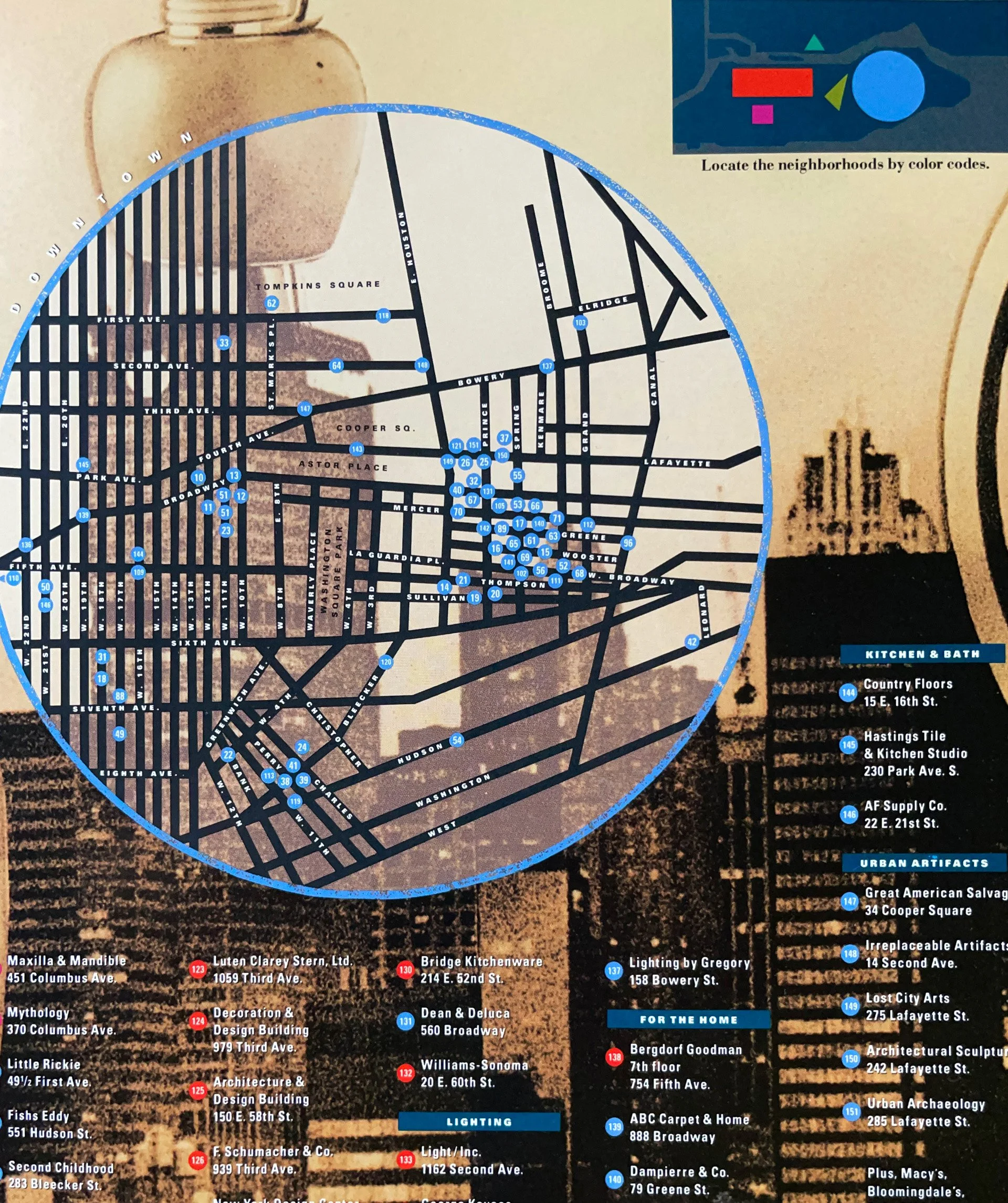

MH Gatefold Maps

At the height of Met Home’s success, many advertisers requested placement in the most highly-trafficked sections of the magazine. This led to the creation of special gatefolds—a premium adjacency to editorial. Toyota sponsored seven pages of editorial with one ad page for a special Los Angeles issue. Morris commissioned pioneering digital artist April Greiman to produce a striking (and useful) graphic — going to bat to acquire a fifth color channel for a Pantone fluorescent orange. For the New York issue, Morris hired photographer Harold Sinclair to create a fanciful Manhattan skyline peppered with sleek tabletop design objects to set the theme.

George Gendron: A theme running through a lot of the Print Is Dead podcasts is this: the thrilling experience of working shoulder to shoulder with a very diverse group of people.

Dorothy Kalins: Mm-hmm.

Don Morris: Absolutely.

George Gendron: Adam Moss, who we did an interview with recently, said one of the things that he loved about his period, particularly at New York magazine, was that there’d be times when an idea found its way into the magazine and someone would say, “Oh, that’s a great idea where’d that come from?” And he had no idea.

Dorothy Kalins: Yeah.

George Gendron: It had been in this fluid group discussion...

Dorothy Kalins: In the air! Right.

George Gendron: You know, and it probably started with something that wasn’t anywhere near the refined idea when it made its way into print and people would start to riff on it.

Dorothy Kalins: The other thing is that people, they urge you on to become more audacious. You become more audacious in a group because you think, “Oh, we can do that? We can try that? We can, ooh...” And I know it’s true. I’ve seen it happen to me. I mean, I come in thinking something, not conservative, but certainly a set idea, and then it just gets better. And there’s buy-in by everybody in the staff. So it belongs to everybody.

I don’t believe that creativity comes from a top down dictate. I mean, it can. And that’s how a lot of businesses are run. But it’s not what I love or thrive in.

George Gendron: Flashback to a moment when I was still a very, very young kid in the New York magazine newsroom. And mostly I was editing and I wrote for the Intelligencer. But I hadn’t really done any substantial writing. And I had this idea, I won’t bore you with the details, but I went to Shelley Zelasnik and pitched the idea, and I barely got the first two sentences out. And he said to me, “What is it you want from me, young man?” And I said, “Well, I really want permission to do the story.” He just said, “Just go do the damn story. If it’s good, we’ll publish it. If not, we won’t.” And that was huge. Because we don’t come from that kind of an environment, most of us, right? And so what you’re talking about in these meetings about being audacious is that it’s, for young people, it gives you a kind of permission to think big and to realize, “Man, I can go off and do this.”

Dorothy Kalins: Yep.

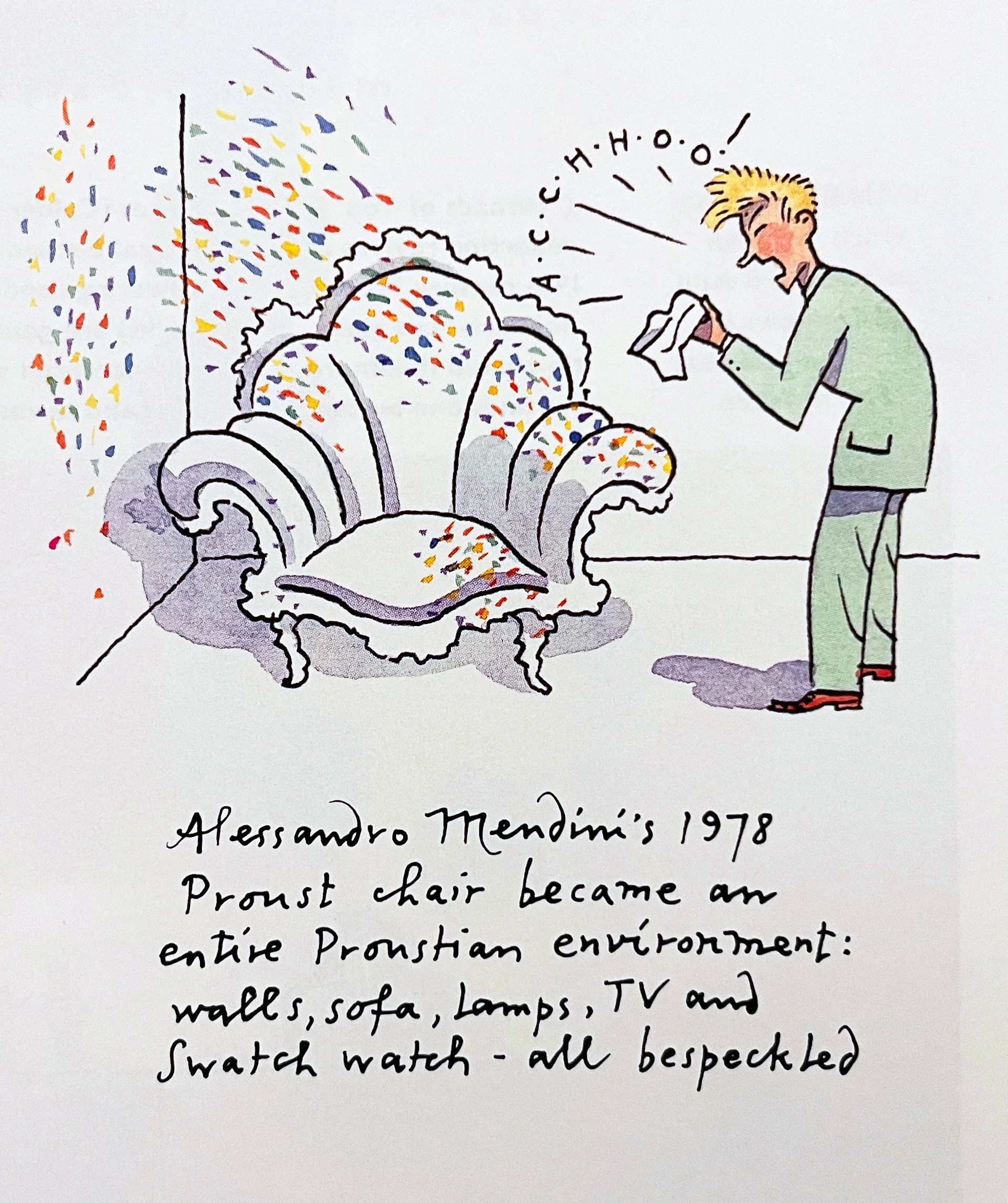

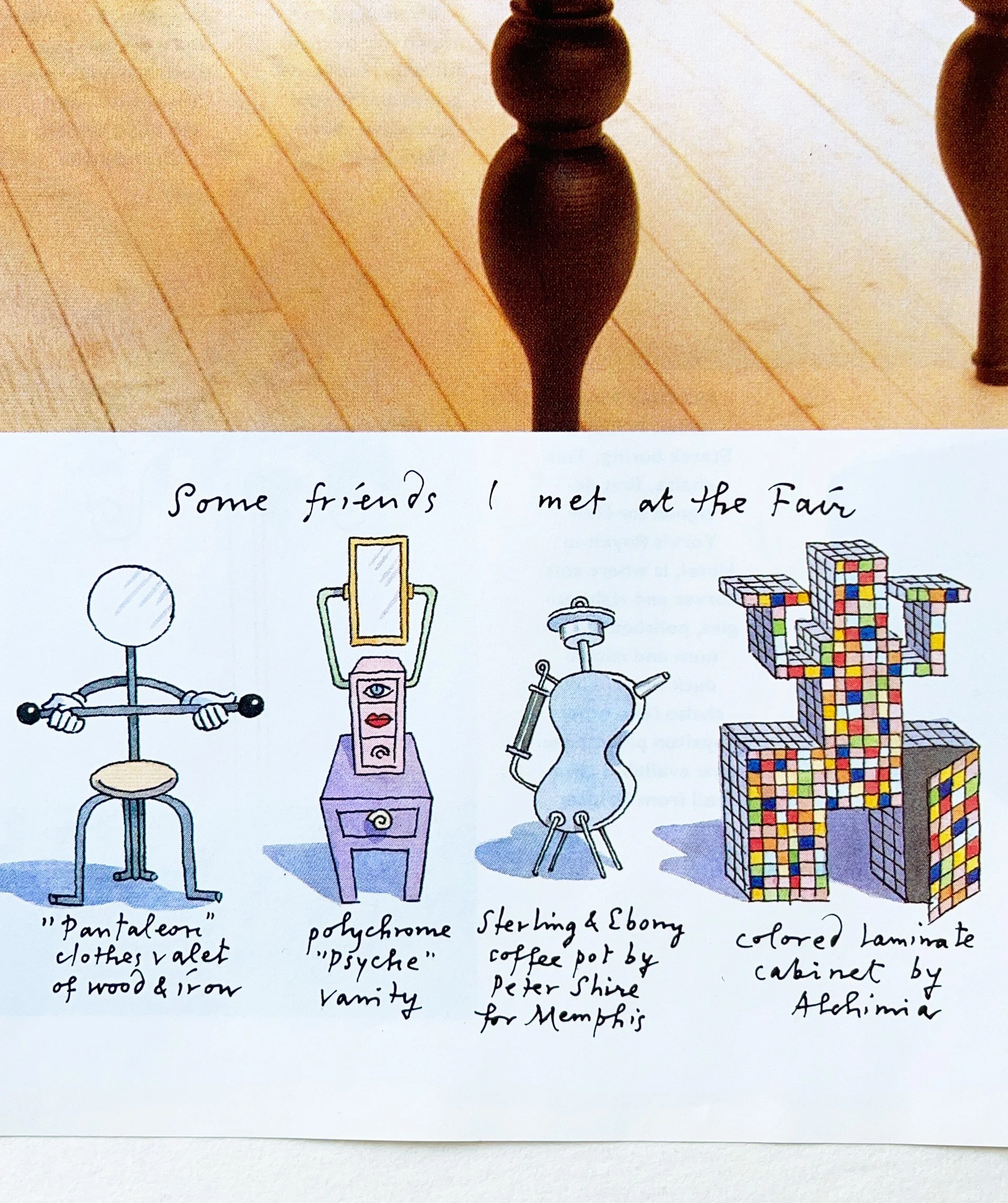

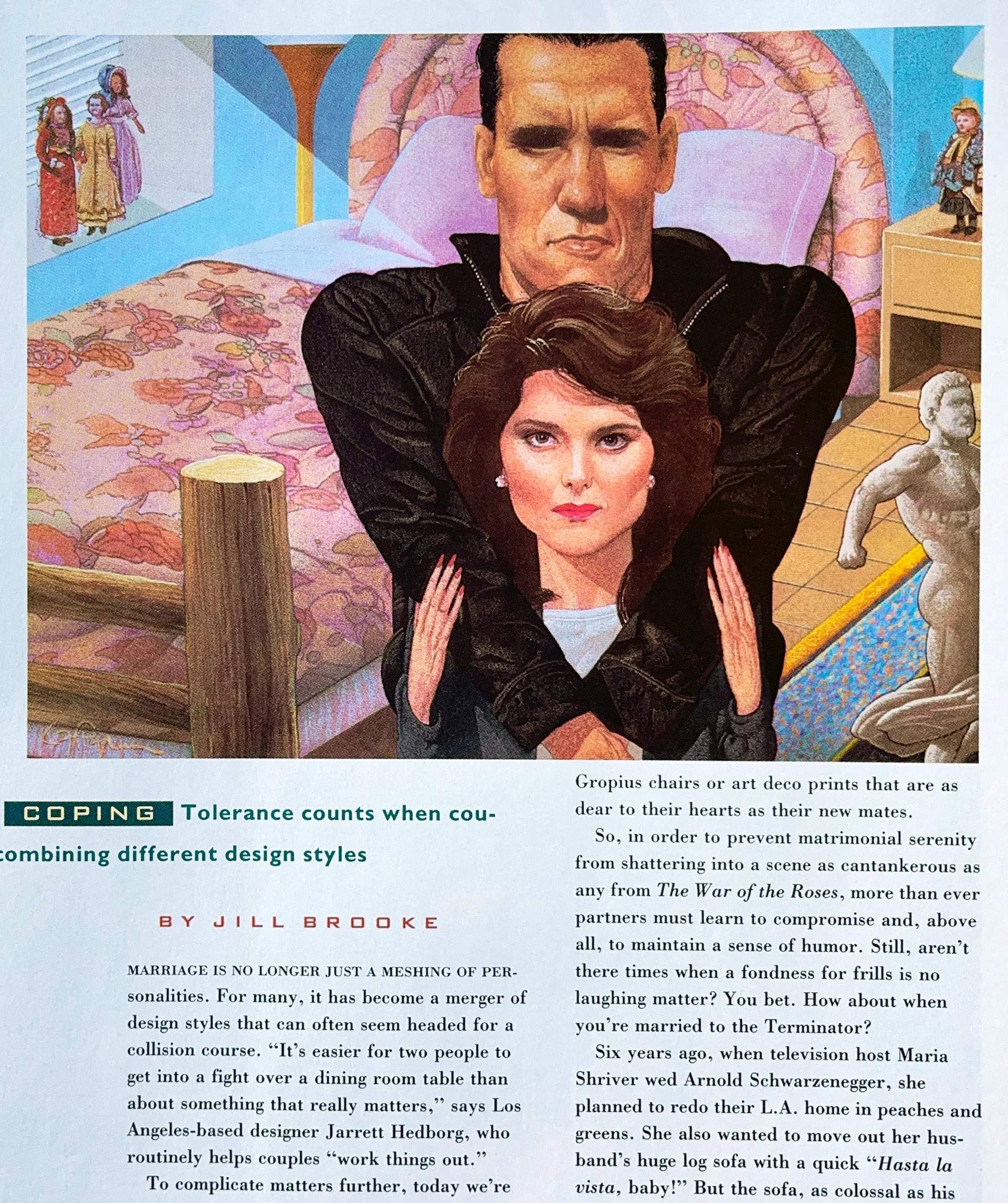

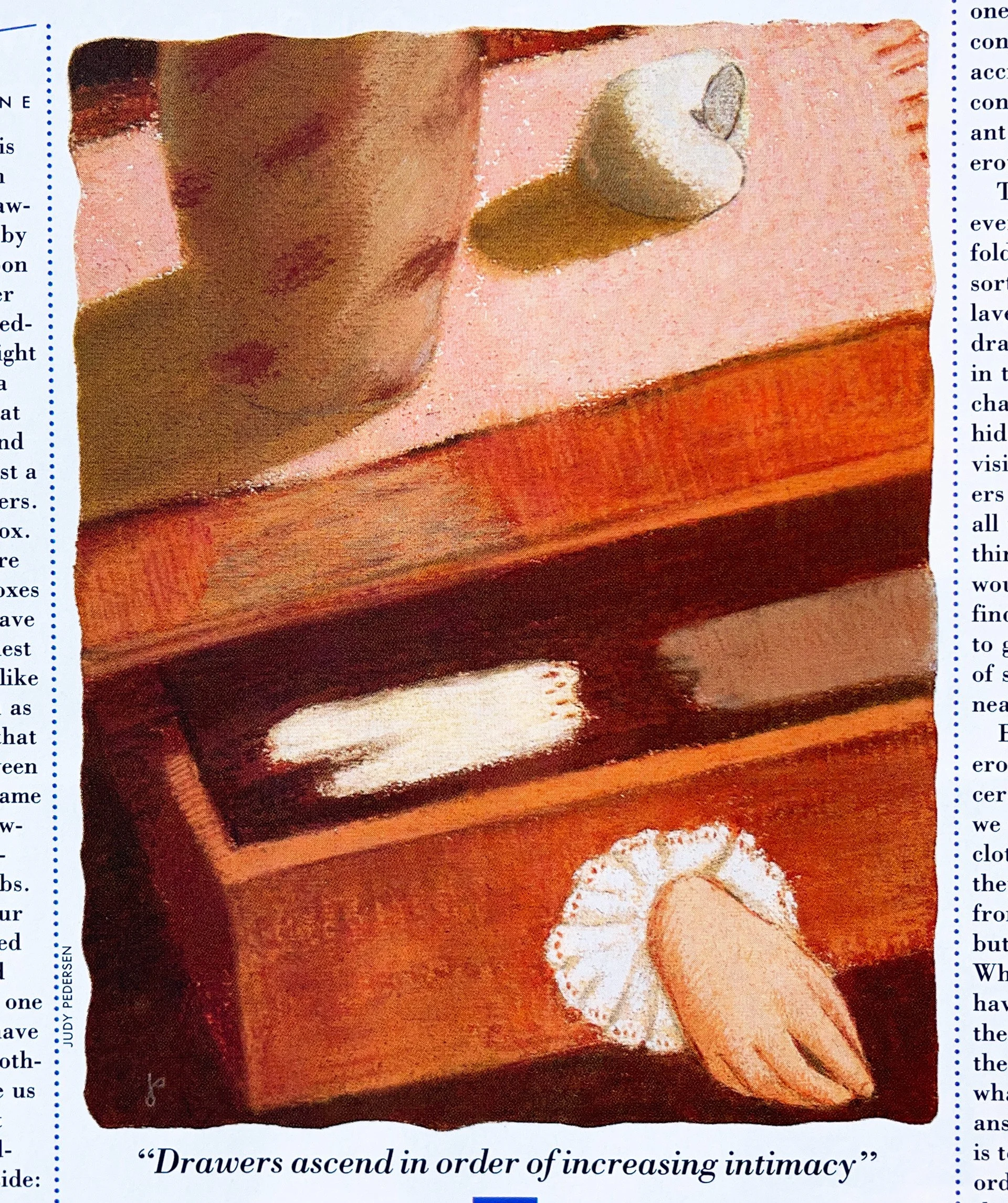

Morris on MH’s approach to illustration: “Though photography dominated our pages, we regularly enlisted top illustrators to bring abstract concepts to life, or to add wit to lifestyle stories. We took all visual storytelling very seriously. Among our talented contributors were: Steven Guarnaccia, Victoria Kann, Barry Blitt, Steve Salerno, Jon Pirman, Judy Pedersen, Gene Grief, Paul Yalowitz, and C.F. Payne.”

George Gendron: One really crucial theme here that I’m glad we’re exploring, we were talking about some of the packaging devices that you guys invented at Met Home that people adored. And I forget the names of them, but you know, the elegant room on the left and then the modestly-priced equivalent of that on the right, the details that you would zoom in on.

Dorothy Kalins: I can tell you exactly where that came from. So my first job was at Fairchild Publications. I was on Home Furnishings Daily and Women’s Wear Daily — which was the hot rag — was next door to us.

And so I read it every day and they had a little feature that was maybe a quarter of a page and they put, “Get the Look for Less.” And that was when I was five minutes out of college. And then we started doing Met Home, and I thought, “A lot of the furniture that we’re seeing just isn’t affordable.”

And the thing that they would say to put us down was that we were “orange crate.” We decorated with orange crates. We never did. Maybe a wine crate, but never an orange crate! And I thought, “Okay, well, what that does is that lets you just take off on an idea and go with it.”

George Gendron: But you also said something else to me that was very interesting. And you said, maybe it was about the details in a room, and you would zoom in and you said to me, “Well, you know, you have to use everything because you just don’t have unlimited resources.”

Dorothy Kalins: Mm-hmm.

George Gendron: And boy, do I think that’s true, this notion that scarcity kind of breeds invention and resourcefulness and creativity.

Dorothy Kalins: Well, it gets back to the tools of magazine making, which is one thing that Don and I really invented when we were doing this together was that you took ideas apart.

Like, I see a room behind you. And I see a sofa, a striped sofa, and I see there’s a lamp on a table and there’s some black and white pictures artfully tilted against the bookcase. And if you call those out and let people focus on that, instead of just room after room… Remember you asked the other day about what our competition was and it was really staid pictures of rooms from Architectural Digest, House Beautiful, House & Garden. They had different levels of taste and style and approach, but we were about journalism.

Don Morris: Right.

Dorothy Kalins: We were about the ideas. We were about conveying the ideas. We were excited about things. And we made our pages exciting. And that had never been done before.

George Gendron: It’s about a sensibility that you bring to something.

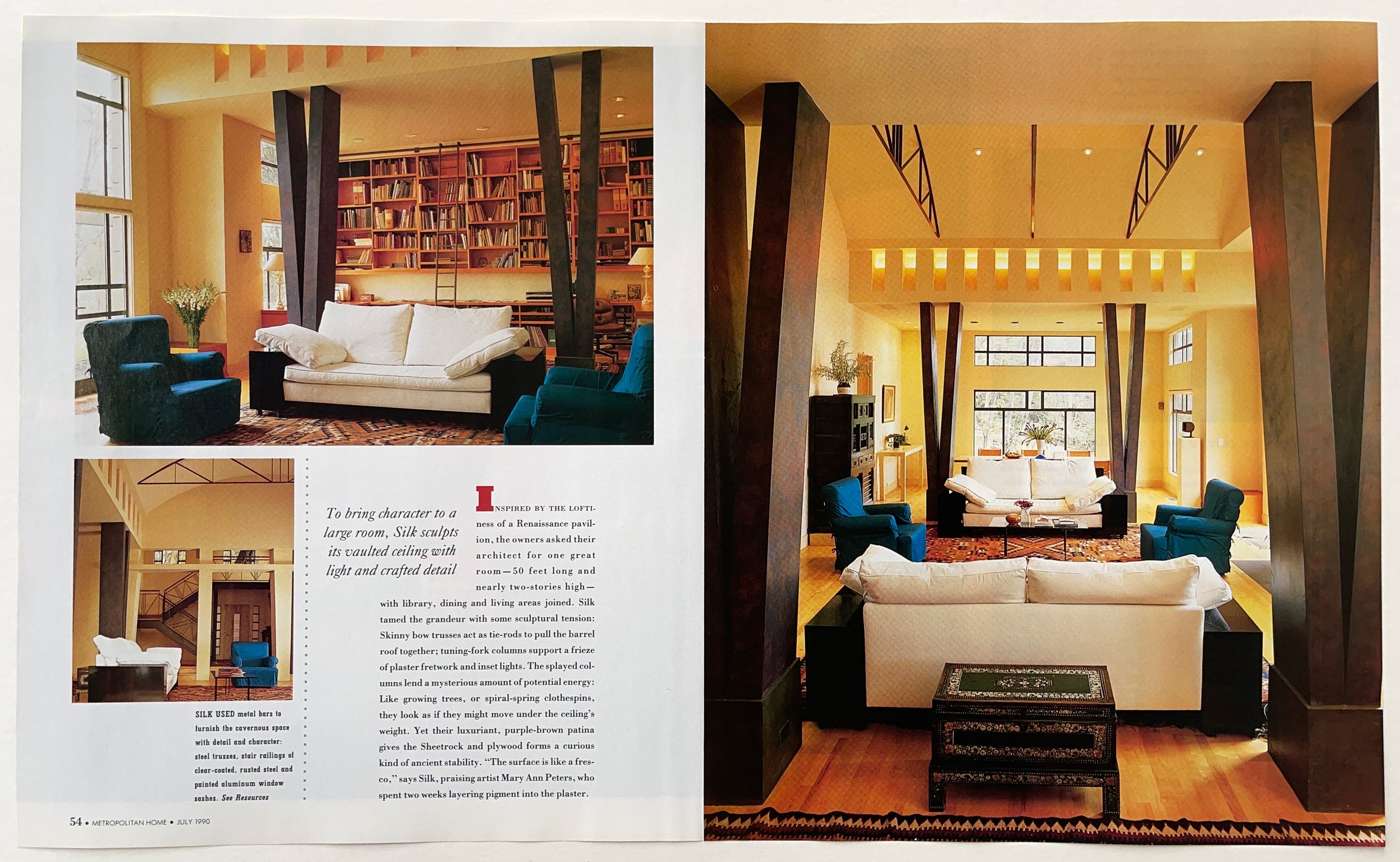

Don Morris: Well, from a formal standpoint, there was kind of a way that interiors were shot. And it had to do with correcting the perspective and lighting every inch. And they were presented in a hands off, finished, almost gallery-like way.

Dorothy Kalins: It was all about pretentiousness.

Don Morris: Yeah. And the mission of the magazine was to get people in there and make it feel like people were in there. Make it feel like it was a real space. So we experimented a lot with the kinds of photographers that we would hire, the ways that we would approach shooting a room. The idea that certain things would fall out and that was okay, because that’s what it felt like when you were there.

And that led to us starting to invent these editorial concepts, these editorial conceits that were more like the way magazines we had admired tackled their subjects. And creating these things that became franchises like what you mentioned was called “High/Low.”

And we had a way to do the logo of that. And we had a way that we would pair the rooms. They were tremendous productions. We had a studio and Carol Helms, one of the main design editors was in charge of all of this and created this. And you would go down to visit and it was amazing to see this whole thing coming together.

But that was just one conceit that was developed to be able to have something that people could remember Met Home by. That was something that gave them a little bit more information, more useful information to take away. And we tried to do that, and that led to themed issues and reports that we would do. We got more and more ambitious in our journalistic approach.

Dorothy Kalins: Yeah. The idea of journalism coming to the field of home design — they had never met before. They didn’t know each other. And not only did we have to do it because we were interested in that, it was our point of difference to our readers.

And our readers were interested in that. That’s what they want. They didn’t want the staid interior — you know, I invented the phrase “buttery sunlight” because we used available light, which meant that photographers wouldn’t light the room. We used to call it “holocaust lighting,” which is when they would come and blast every sense of light away from the room.

But it started with that. So everything had to fit that. You could be playful with where you put captions, and you could play with the language of design. You could play with the language of home. Because we wanted it to be about personality. We didn’t want it to be just about pretention.

“I always believed that you get the smart people in a room and the best ideas happen. You learn by being, by experiencing, by traveling, by talking, by all being in the room together. And I just believe there’s a certain chutzpah that happens when the people are in a room together.”

George Gendron: I am sure you’re aware of this, and I’m sure you heard this many times, but the effect that all of this had, among many other things, was, I’m going to use your word, Dorothy, from when you were talking about one of the effects of being in a group and brainstorming, and that is it gave readers a certain kind of permission to think about the fact that they could express themselves through their homes as well. And that this was not a pursuit of the wealthy. You didn’t have to be able to afford an architect. And perfection wasn’t the goal. These homes looked lived in. They looked like places that would be fun to entertain in, to cook in, have friends over. There was a kind of invitation.

Dorothy Kalins: At the same time, we did cover who we thought were the most influential architects in the world. And designers. Because the ones that we gravitated to, and the ones who we featured, were people who wanted life in their rooms, in their houses, in their homes.

They wanted energy, and warmth, and human interaction. They didn’t want the kind of sealed off protectiveness that a slipcover gave you that you wouldn’t dare touch.

And I think the way you used captions, Don, and the way you were able to manipulate the elements on the page was always lively. It gave a reader something to do instead of just turn the page, turn the page, turn the page. There was always a reason to stop and read something and delve further into it. So it was very interactive before there was anything interactive in magazines.

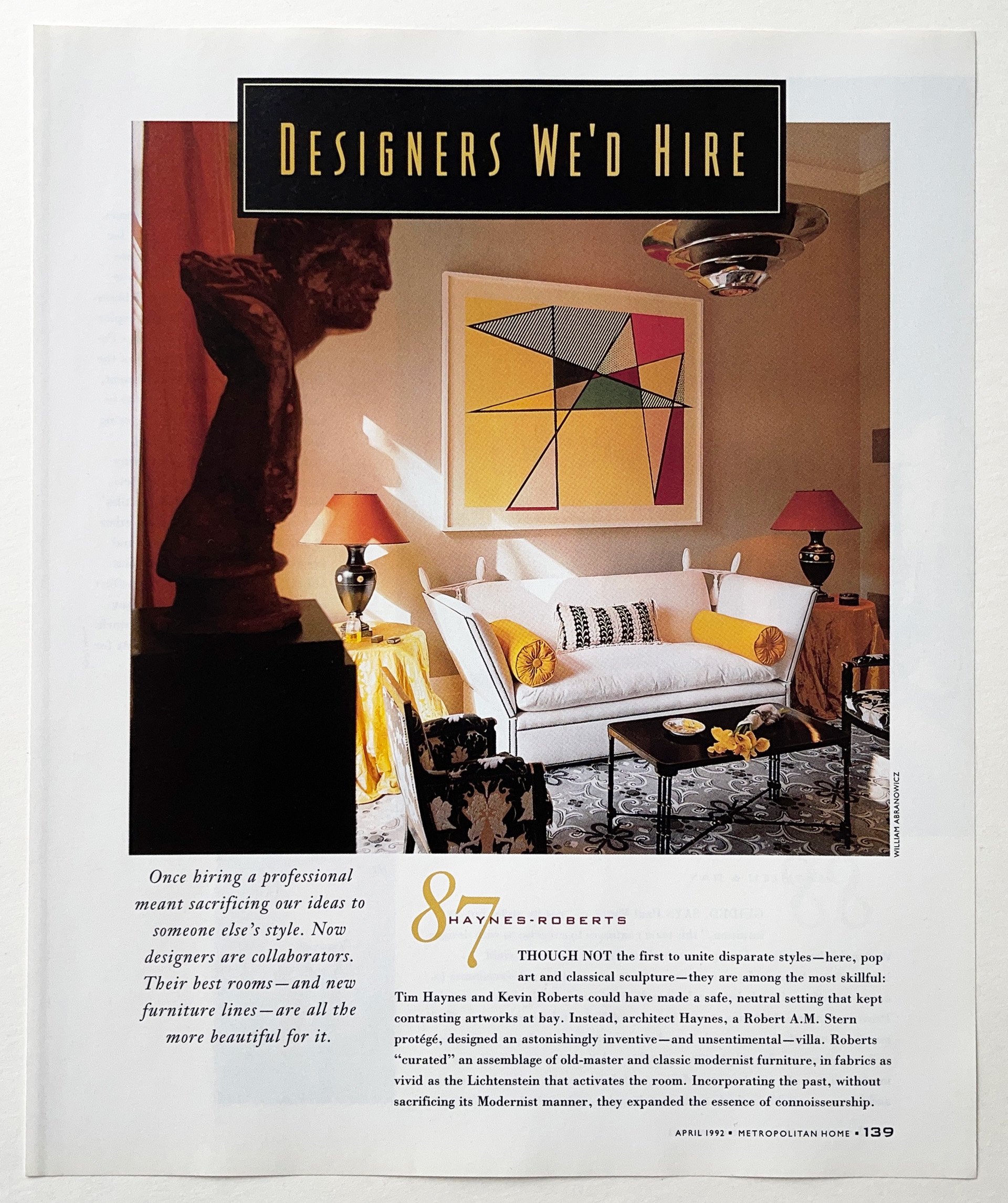

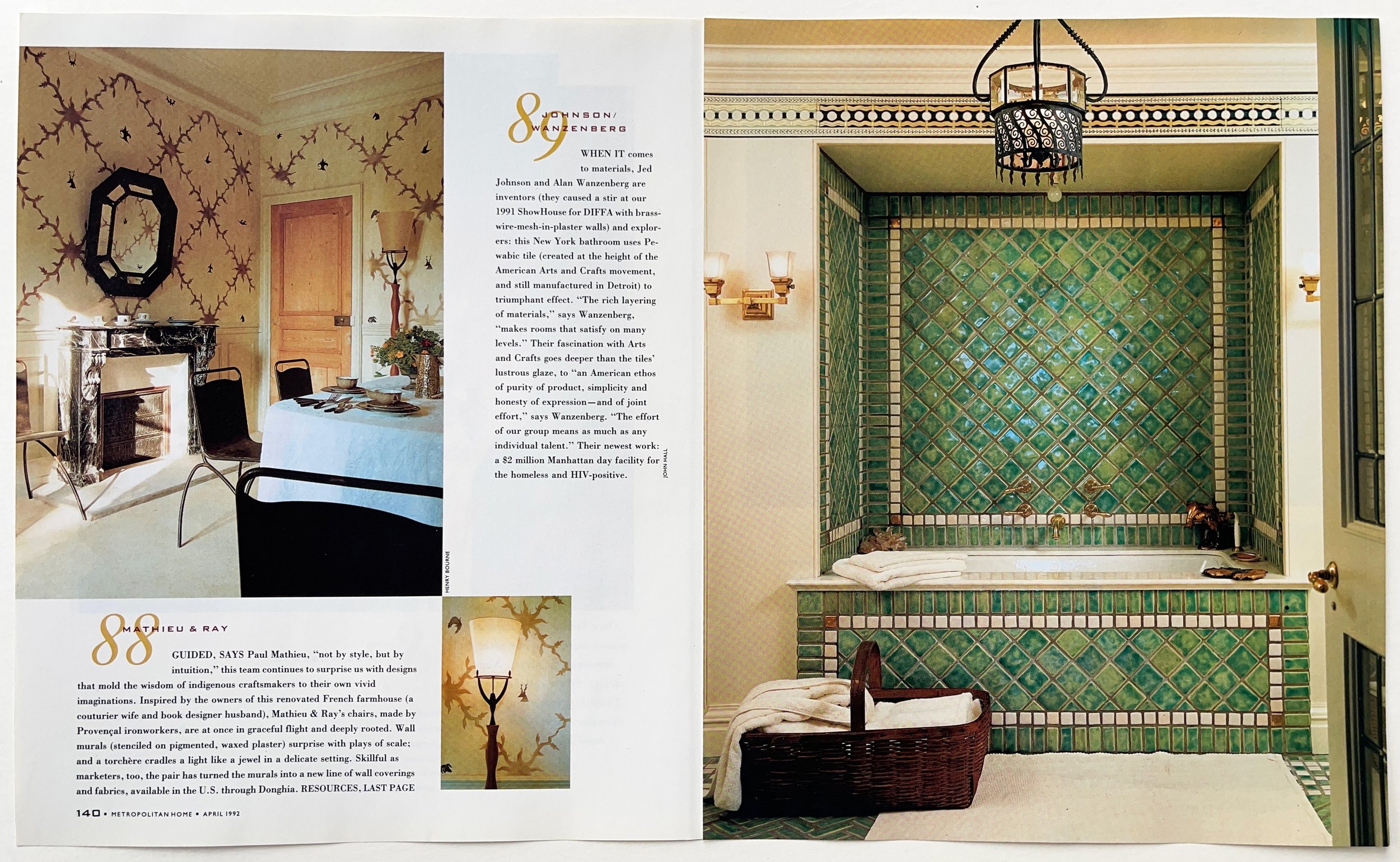

Don Morris: Editorially, again, looking at the landscape, magazines that centered on this subject were pretty siloed in their point of view. You were modern, you were country, you were traditional. And we took a much more humanistic approach. People were walking through this world and they were exposed to Italian design and they were exposed to amazing antique pieces that spoke to them. And so we gave them permission to, to take what they saw in the world that they loved and help them to figure out how to make sense of that or to show some approaches that shows how the sleekness of some things can work with the sort of more ornate nature of other things.

And so this whole kind of personal style was celebrated and explored. And that also came through with a lot of the designers and architects that were putting their mark on the world with what they saw and what they were putting out there. What it was about them that made them different.

And we helped to expose people to a lot of different design trends, but also give them some sense of how they might be able to bring that into their life. So it was very relevant. It wasn’t like that kind of temple-like point of view.

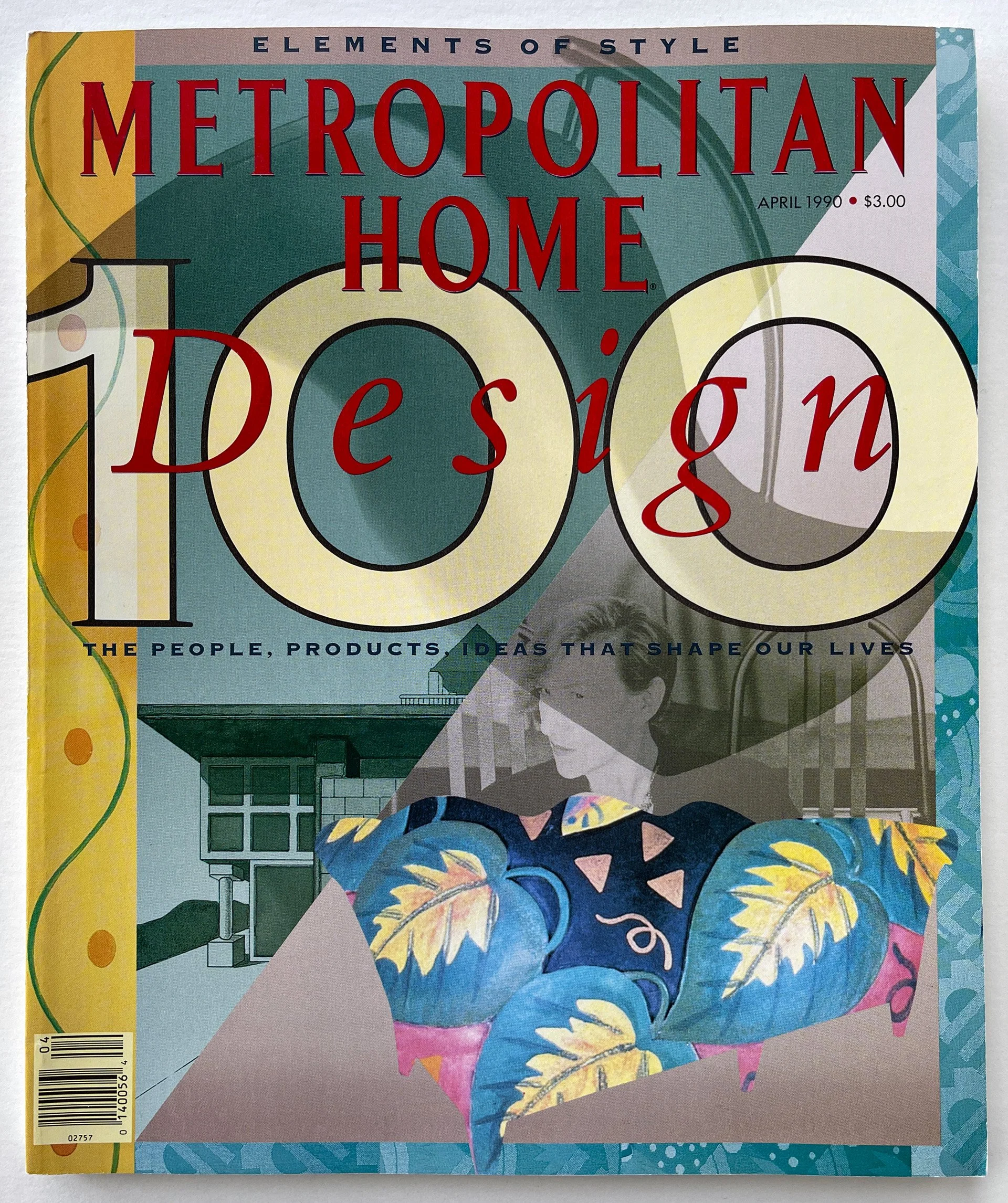

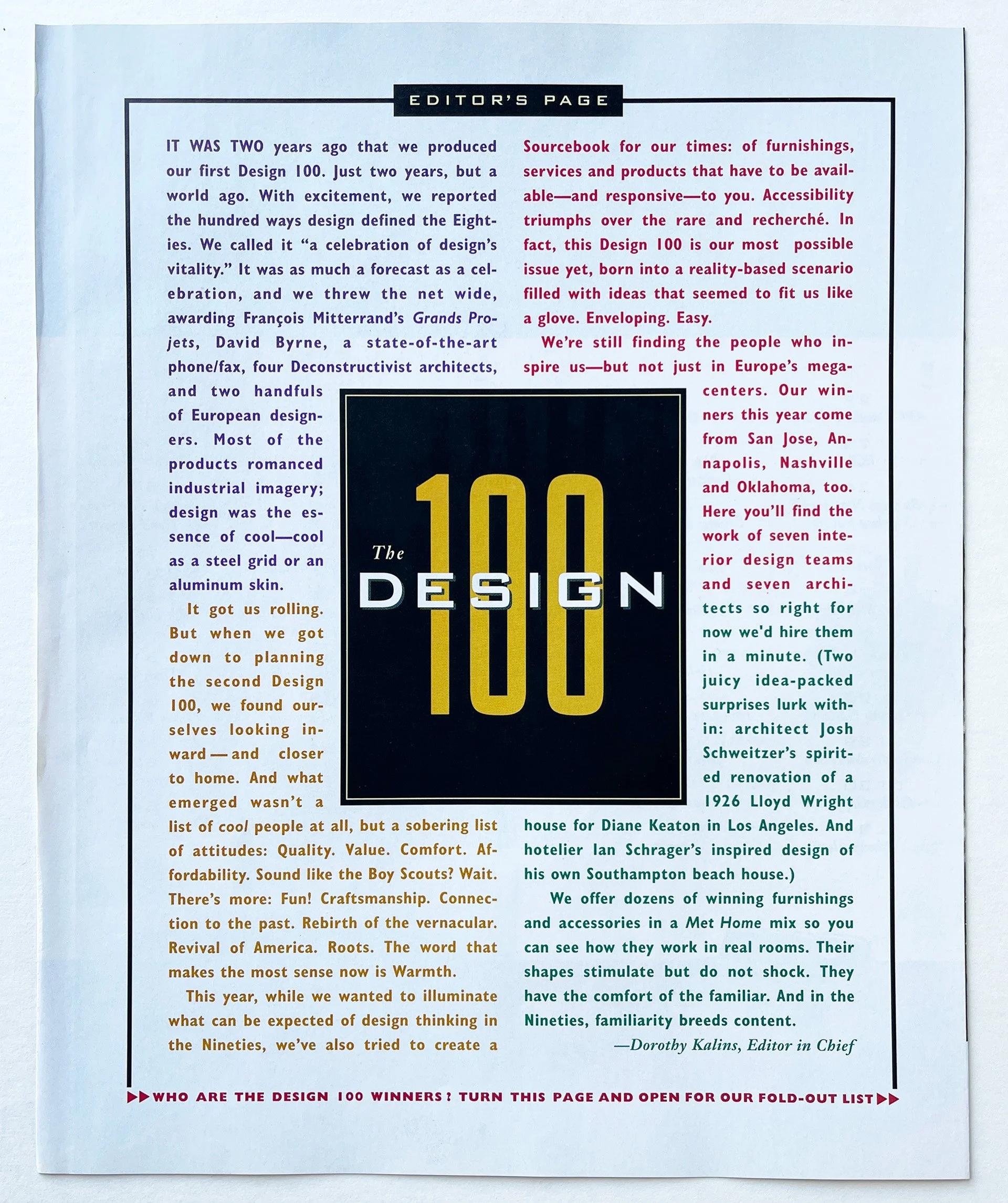

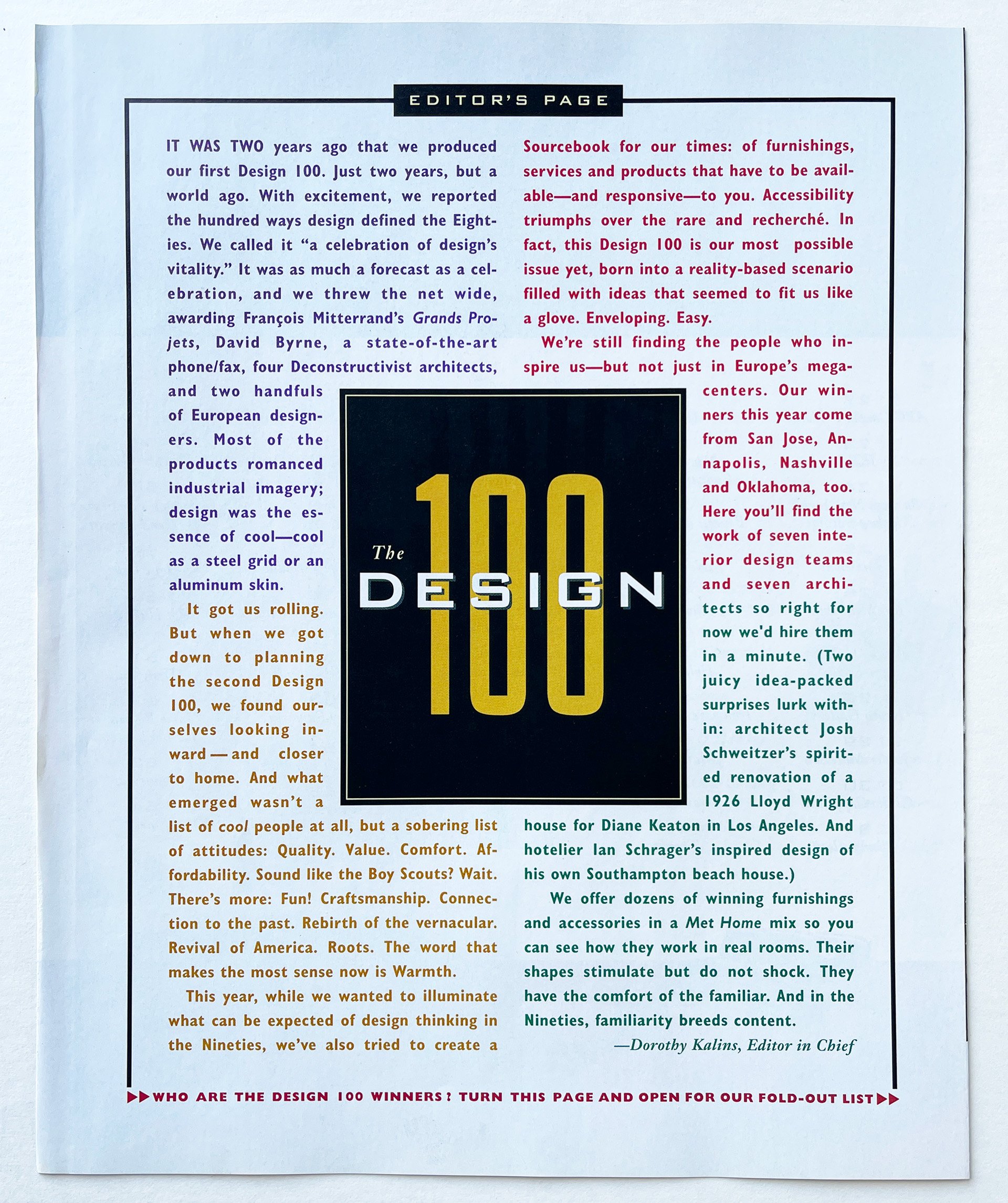

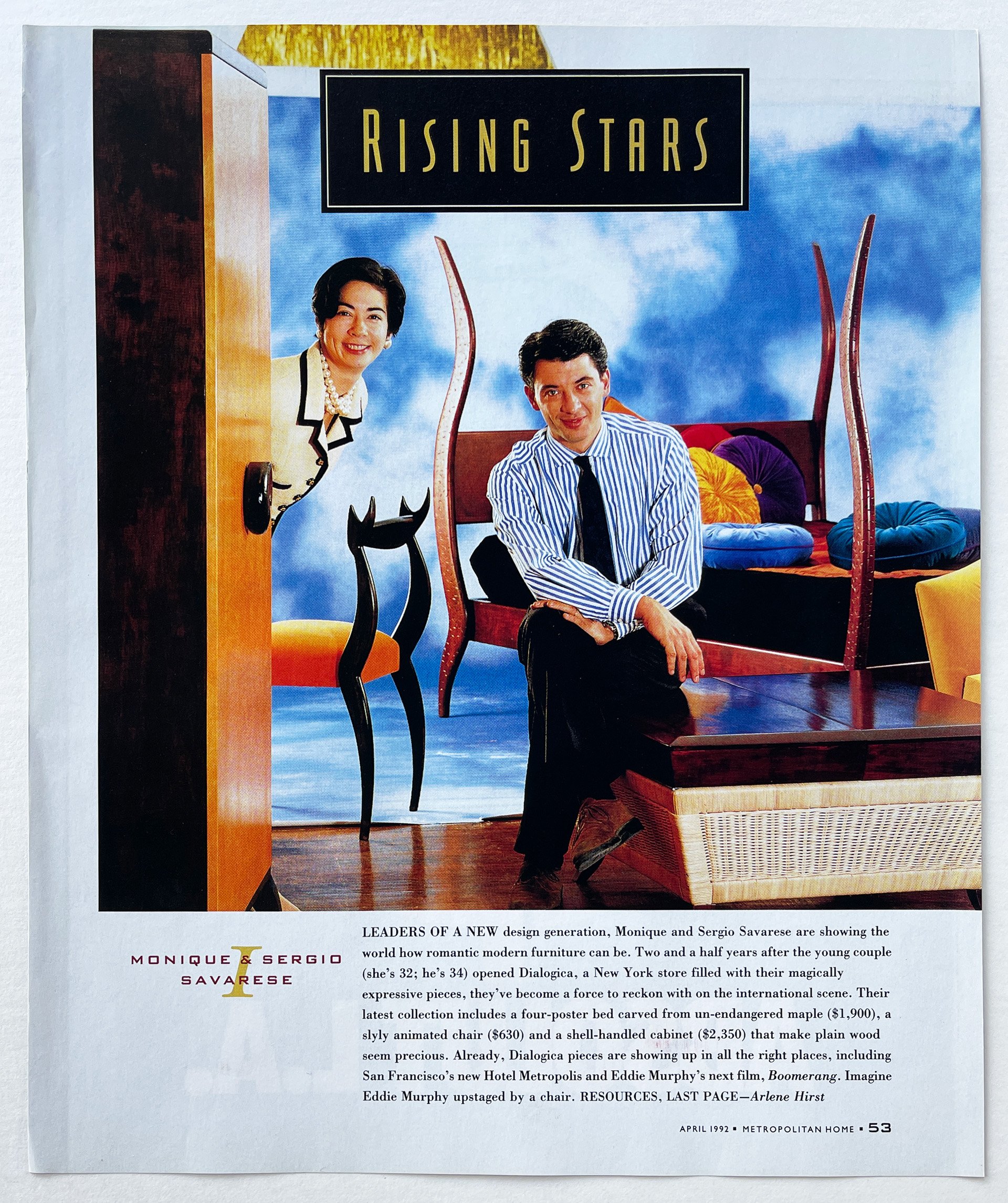

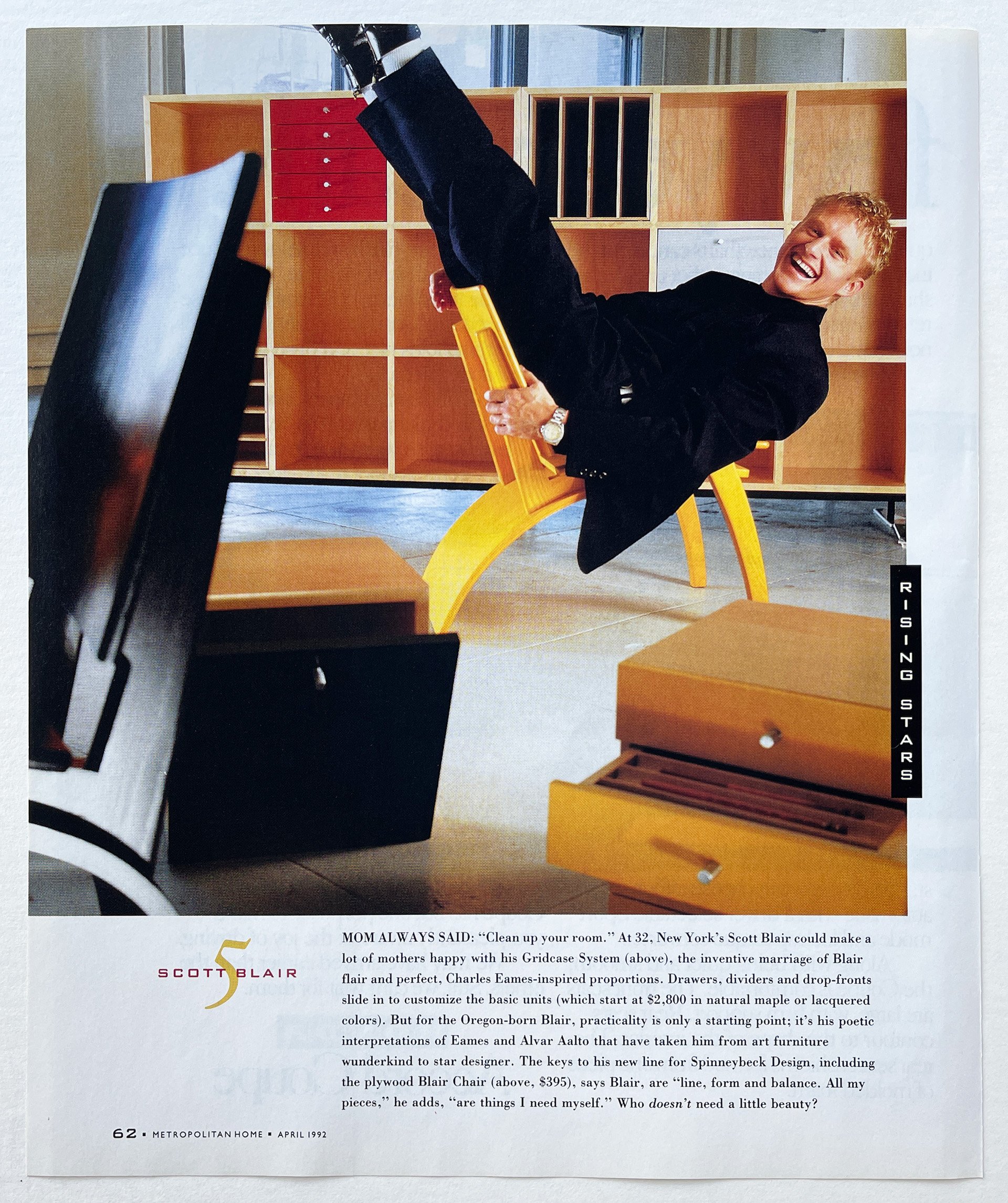

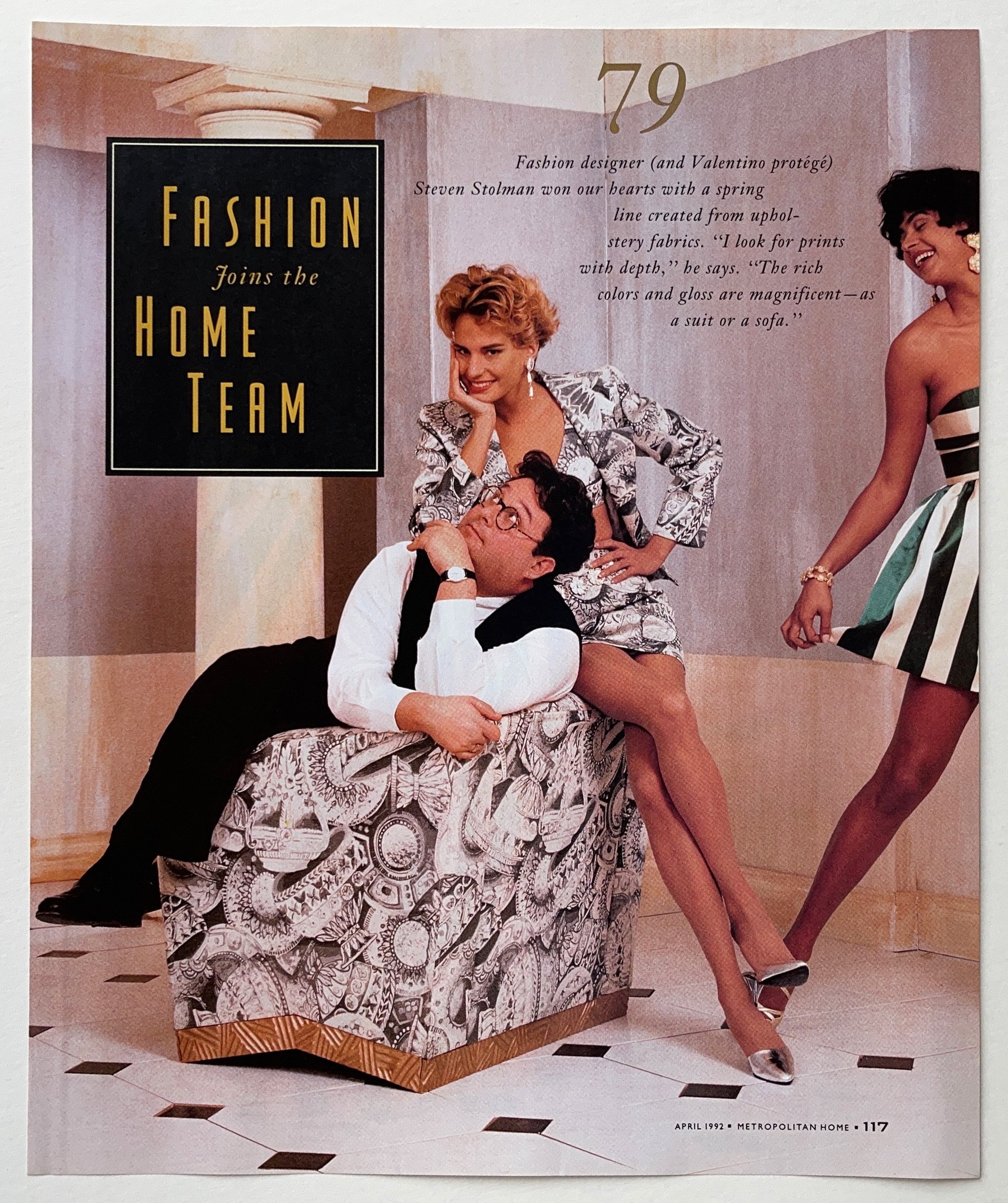

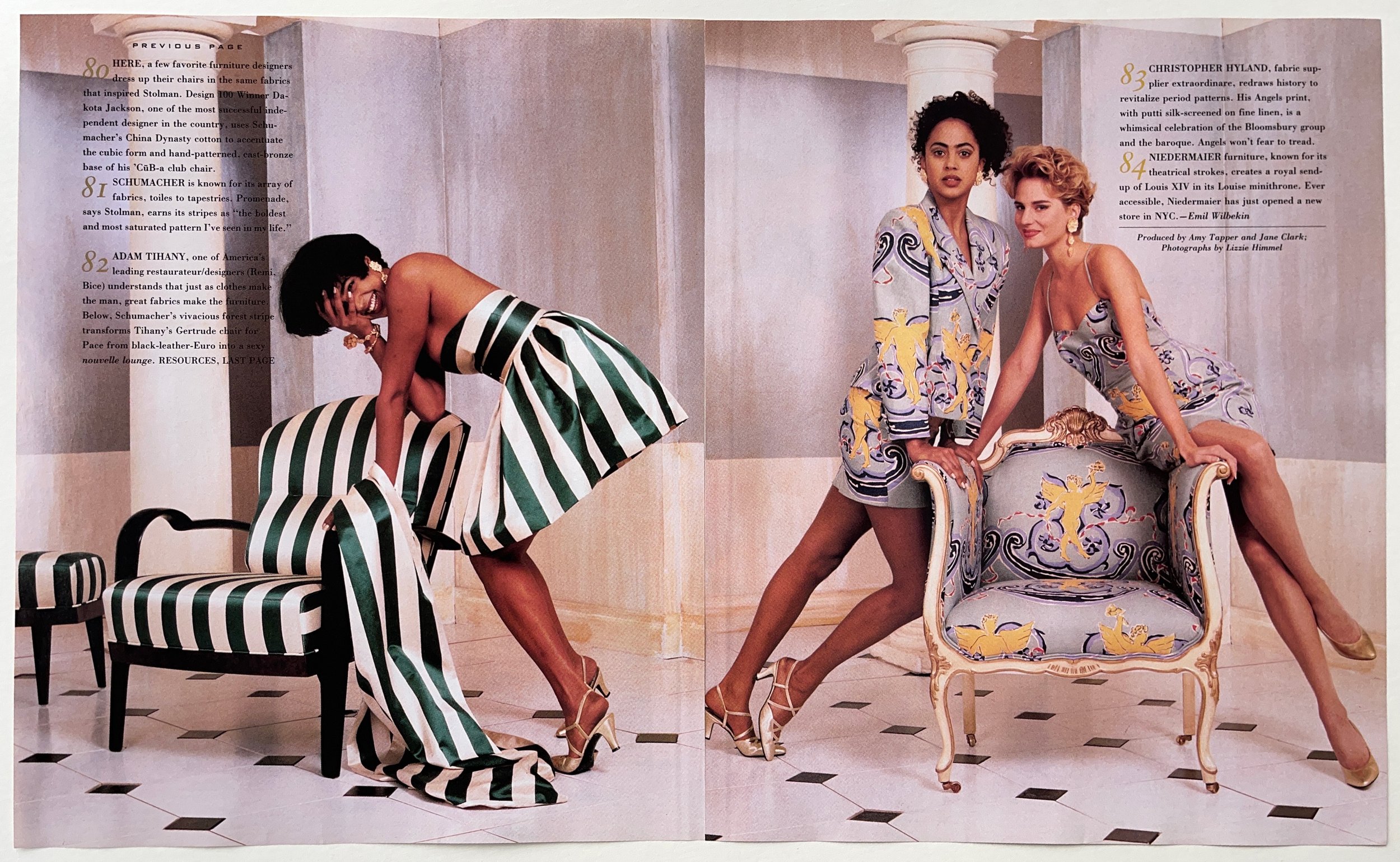

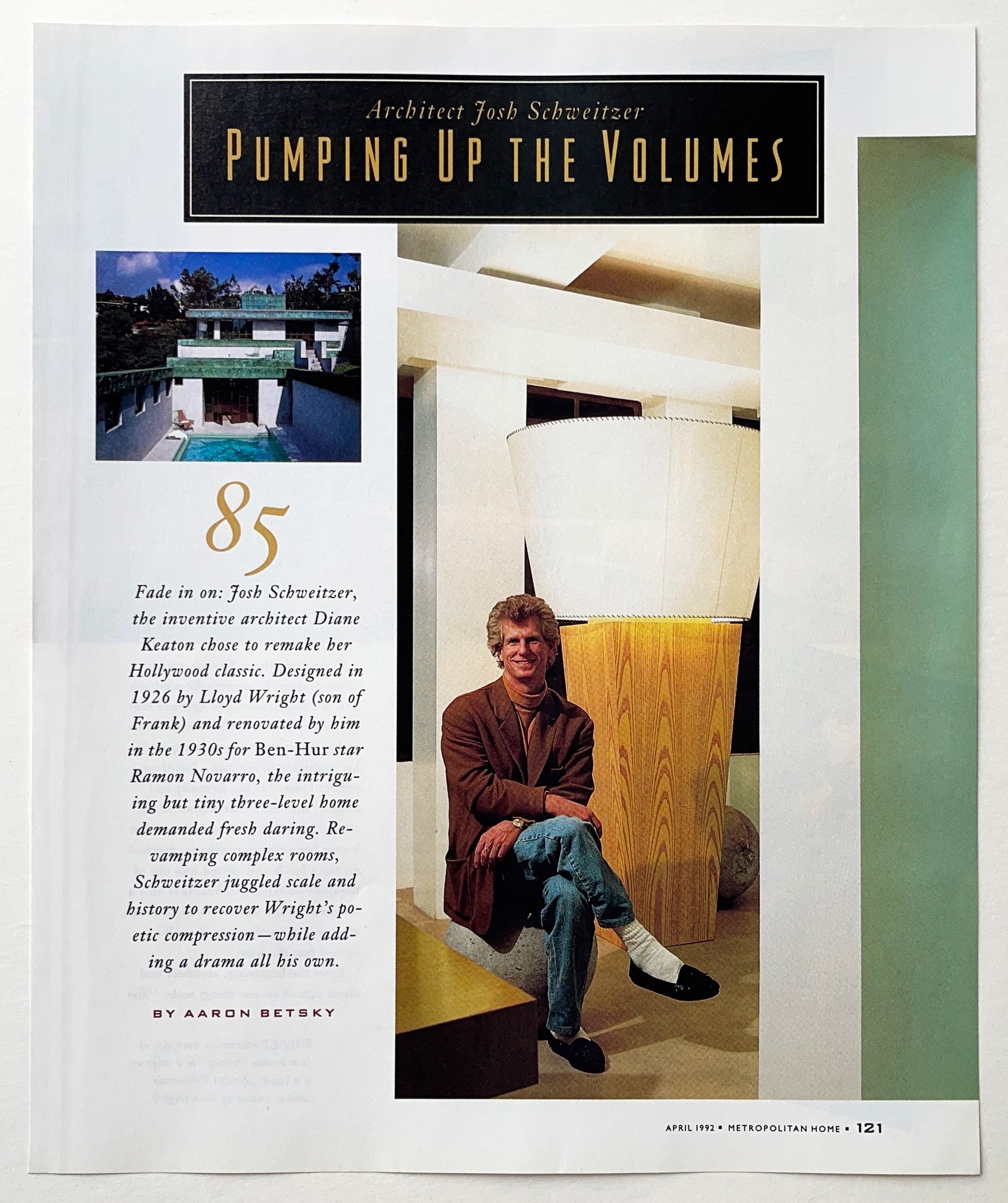

The Met Home Design 100

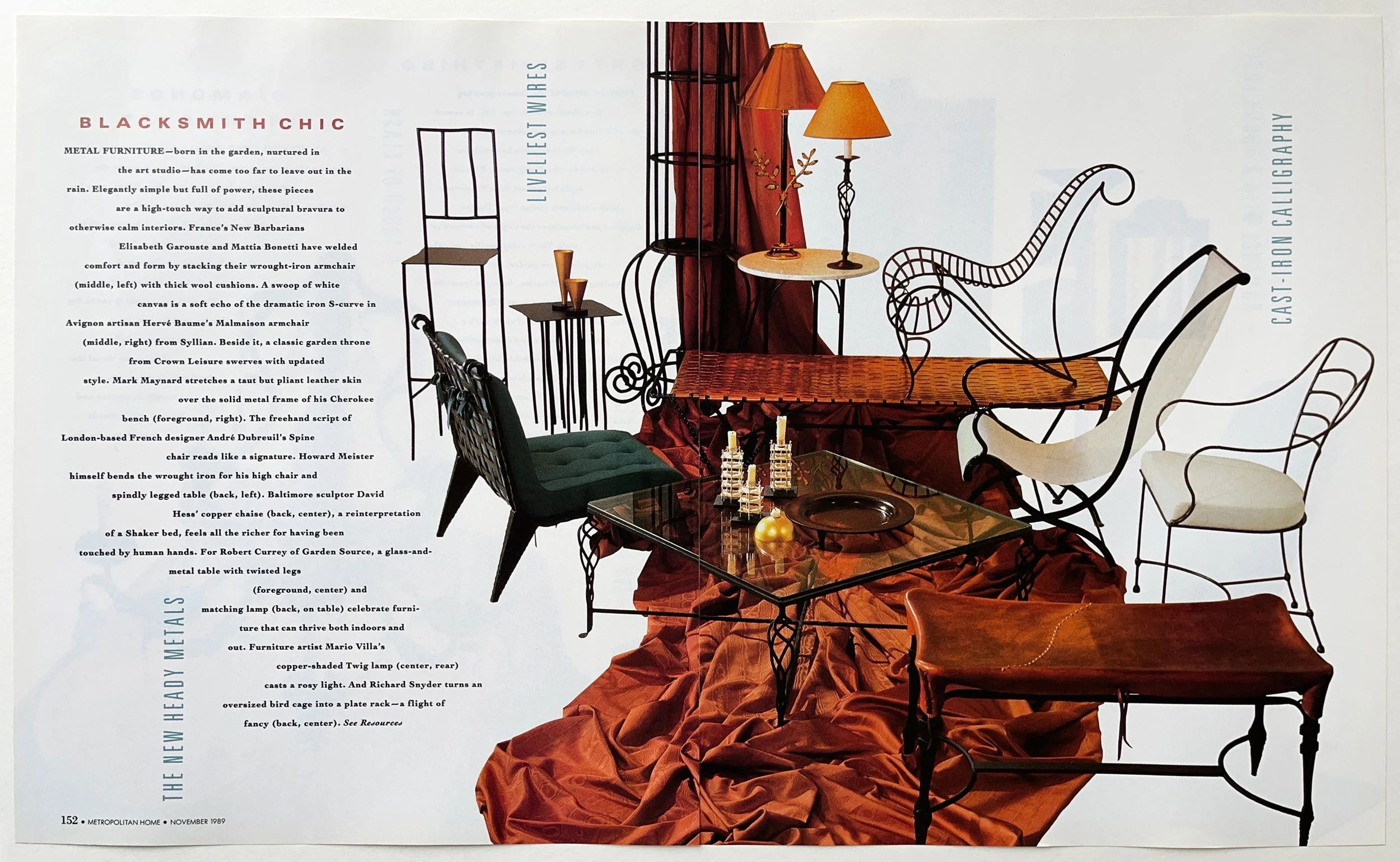

The Design 100 was an annual special issue that honored superlative invention and creativity in international design. The entire issue was designed as a one-off, with distinct typography, grid variations, color palette, and graphics. Art Director Kayo Der Sarkissian, whose incredible eye for detail and encyclopedic memory helped establish the rigor of the magazine’s evolving design.

George Gendron: Don, I want to go back to something we were talking about earlier, which is the transition you made from New York magazine to Met Home. And one question I should have asked back then, I’m really curious about, was, did you and Dorothy do a really dramatic redesign of the magazine all at one time, so that the look and the feel of the magazine, the typography, everything changed from one issue to the next? Or was this something that evolved over a period of time? Or a little of both?

Don Morris: I had to critique the magazine to get the job. And there were certain things that I saw as being sort of newspaper-like in their simplicity. And I’ve talked about how the verve of the subject and the sensibility of the subject could be more in the pages. And so from the beginning I was exploring that.

I was always, again, with that model of Esquire and developing a very strong relationship with the reader, I was interested in finding the right vessel for Met Home. For these voices that I was hearing in the halls that were telling stories. And I wanted to make a better, more in-step vessel to what it was I was hearing and what it is that we were reporting on.

And over time, I was there a while. I was there I think eight years, and I think we did three major redesigns. So we brought it to a place where I think we had a lot of tools that we felt were really perfect for what we were going to try to do. And we wanted to explore that.

We worked with grids a lot. We had sort of an elaborate set of tools. We drew our own type. But then there would be kind of constant evolution with the way that we would bring illustrators in, the kinds of photographers that we would invite. There was a lot of experimentation at that time with having people from different fields come in and bring that point of view to a new subject.

So we were inviting people that were not really in interiors to help portray the subjects of the magazine. We were shooting a lot more people, so we had great portraitists come in. There was a lot of evolution there, as the content sort of required.

George Gendron: Now we want to talk about something that was really, really striking about Met Home that had nothing to do with magazine making per se, but it was the unbelievably public support of the magazine for AIDS treatment, AIDS research at a time when there wasn’t even a vocabulary to describe what that was. During the later part of the ’80s, we would start to talk about social responsibility. We would start to talk about corporate social responsibility. But that language, that vocabulary, didn’t even exist then. So I’m curious about how that evolved. And I’m also really curious about what was the response of your owner?

Dorothy Kalins: That’s such a great story because here we were the “Lefty, Pinko, Radical” magazine of the Better Homes and Gardens company, which, by that time, had bought the Ladies Home Journal. So, I mean, they were just entrenched. My boss was the head of the magazine group at Meredith and they had dozens and dozens and dozens of magazines. And I was the one who would, you know, mess up the sandbox.

And we decided to do it because the people who we covered and our readers were getting sick. And it was very early on in this process. So early that when we actually decided to do a dinner and a gala to raise money, I called the director of the Museum of Natural History and they said, “Well, sorry. AIDS is not an approved disease. We can’t let you rent the hall.”

And I had a conversation with somebody at Canada Dry who said, “We don’t know how this disease is spread so we can’t support you because you might be able to do it by sharing cans.” Those are two examples of how resistant — the head of the magazine group at Meredith said, “This is so radical and this is so not in our wheelhouse.”

And here’s what was also important. Not only could Don and I work really closely together, we work really closely with our publisher. We happen to have a nutty, idiosyncratic, very effective publisher who was all for our doing something that would break through the sameness of our field.

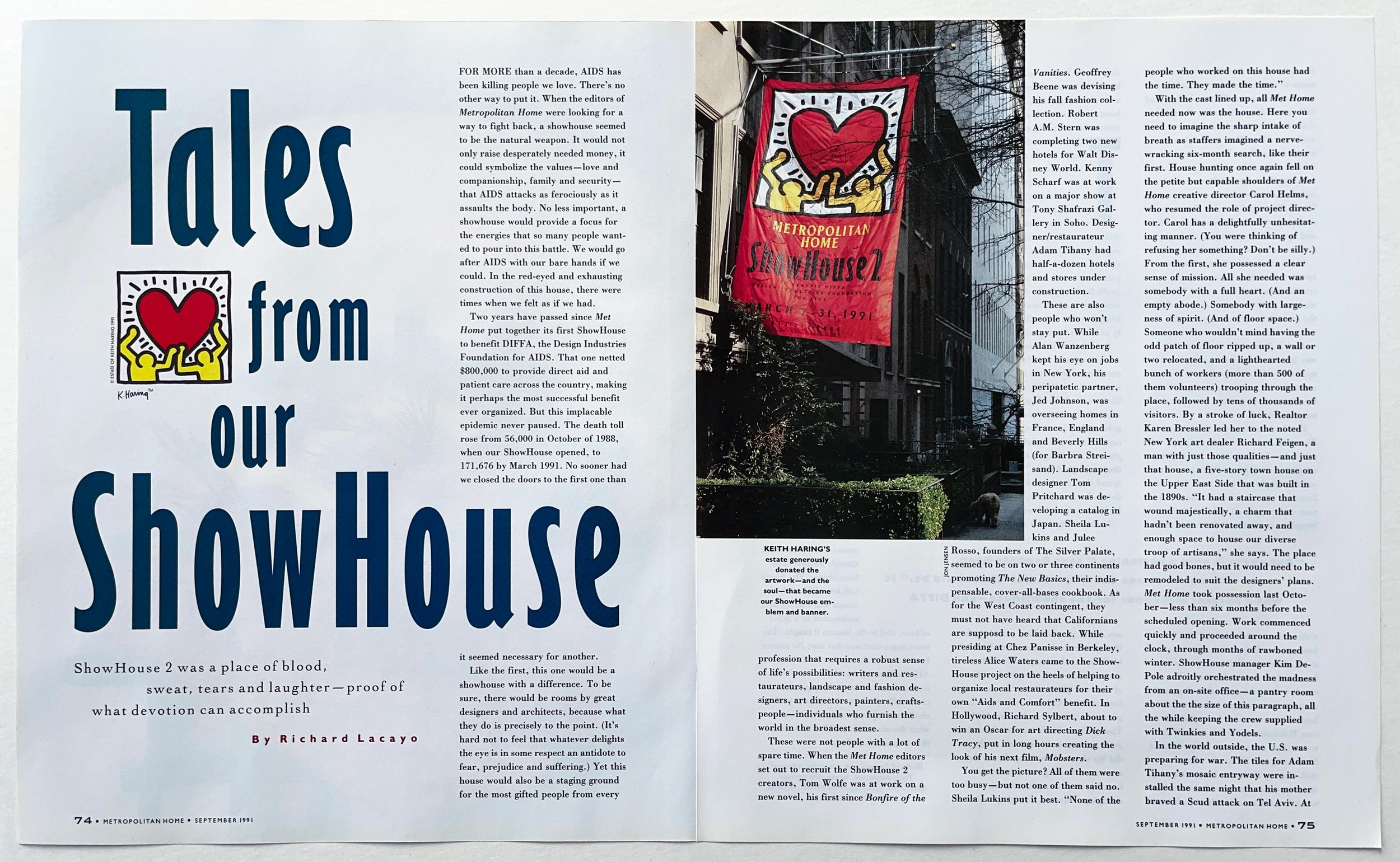

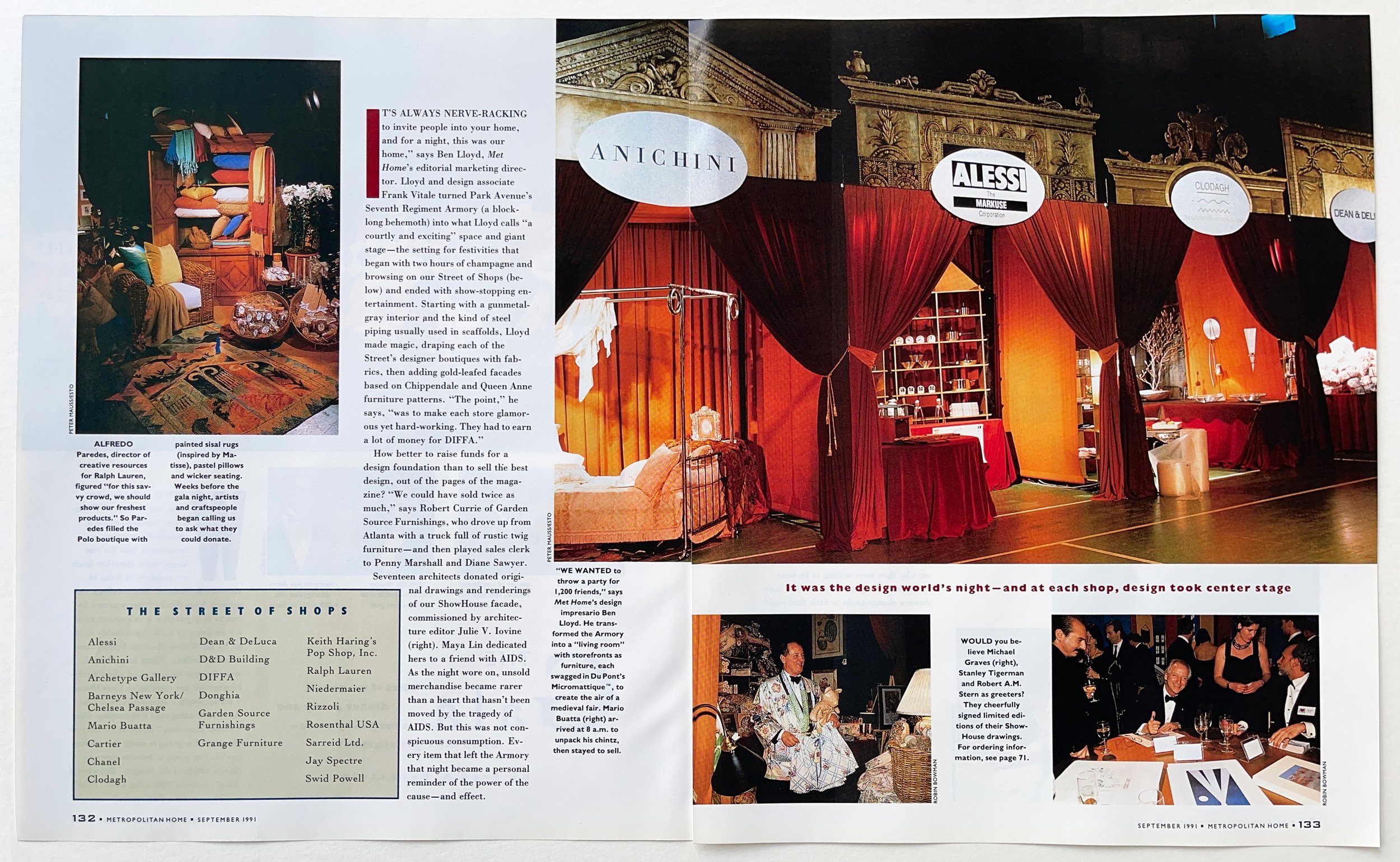

The Met Home Show House & Gala AIDS Benefit

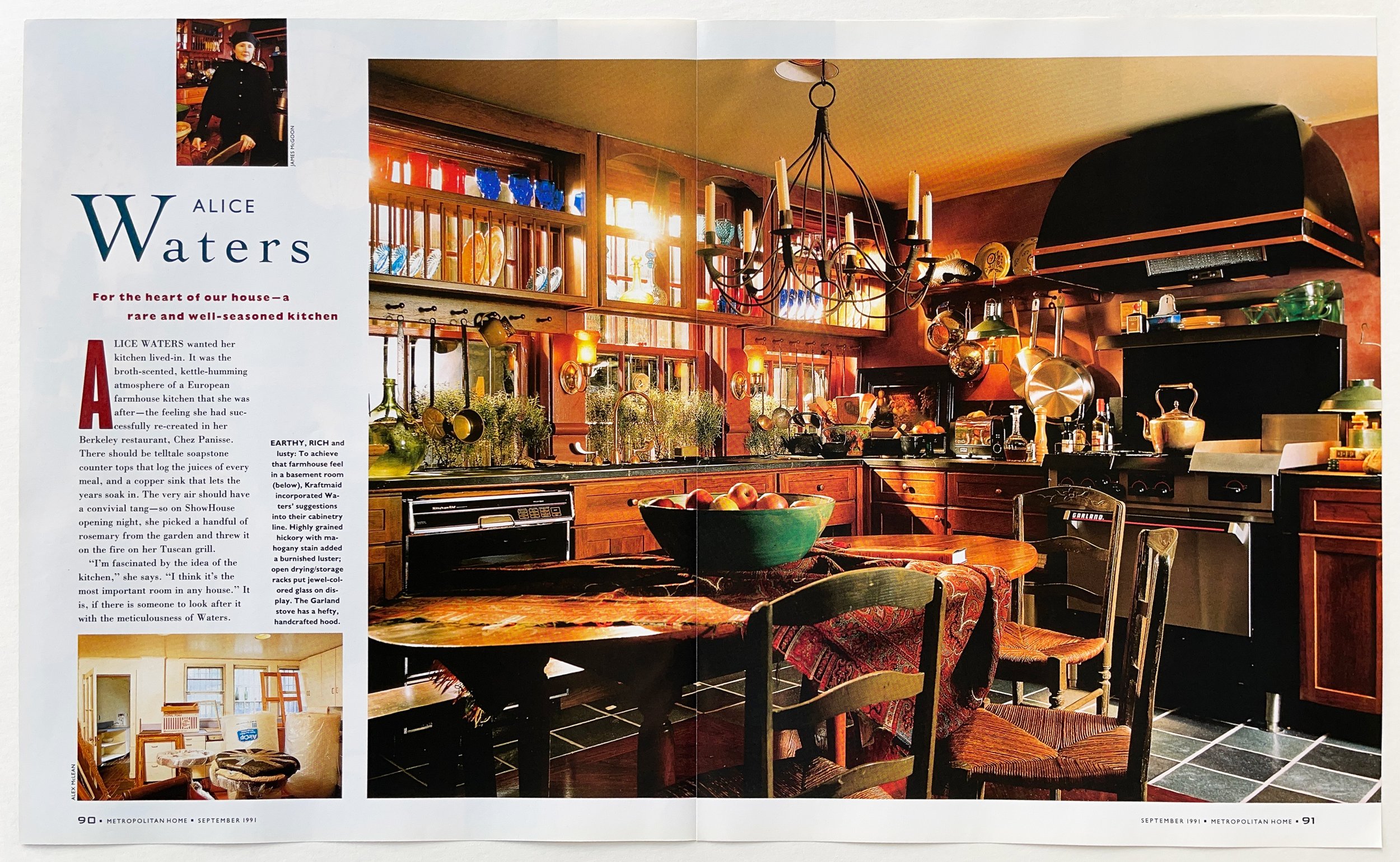

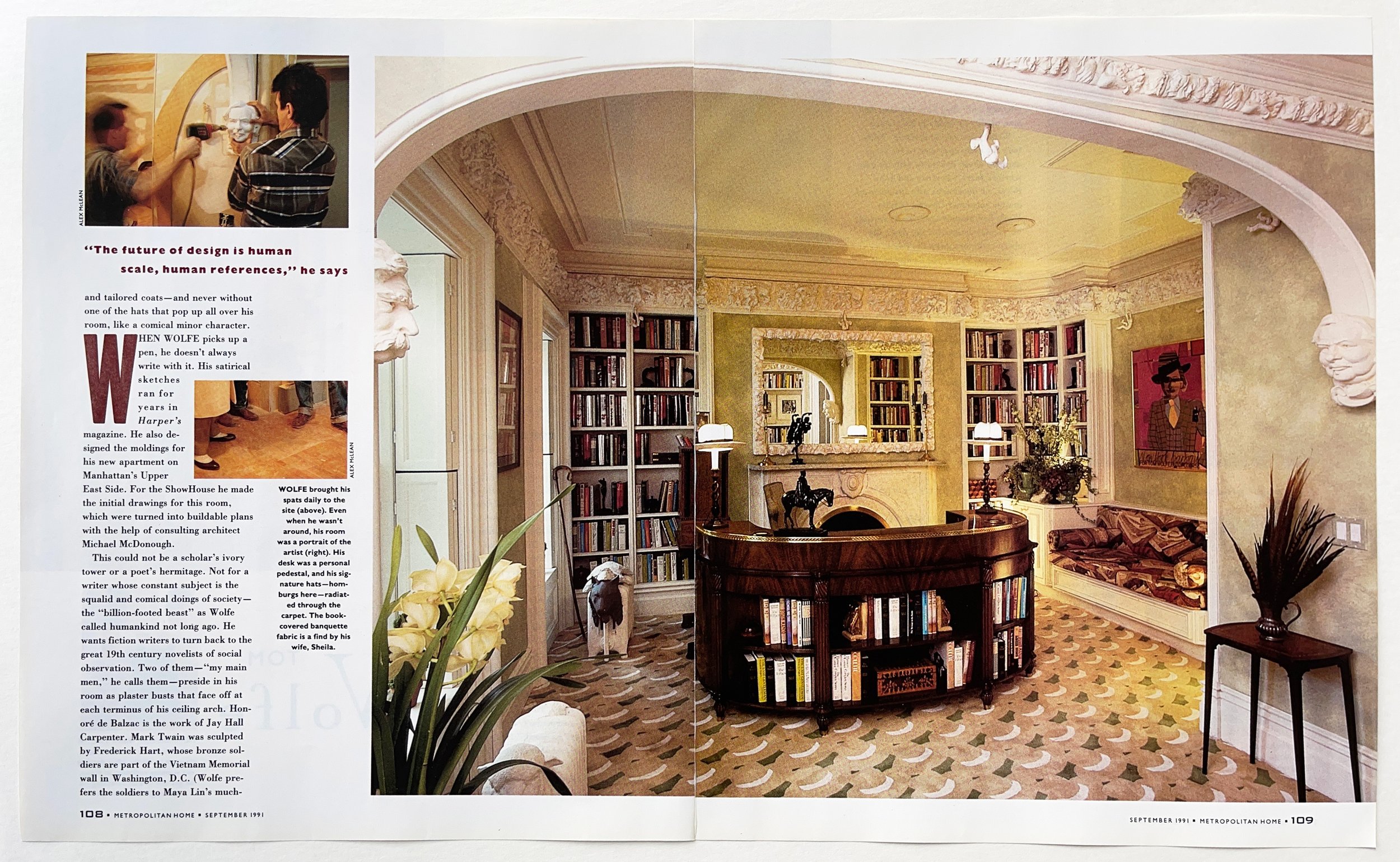

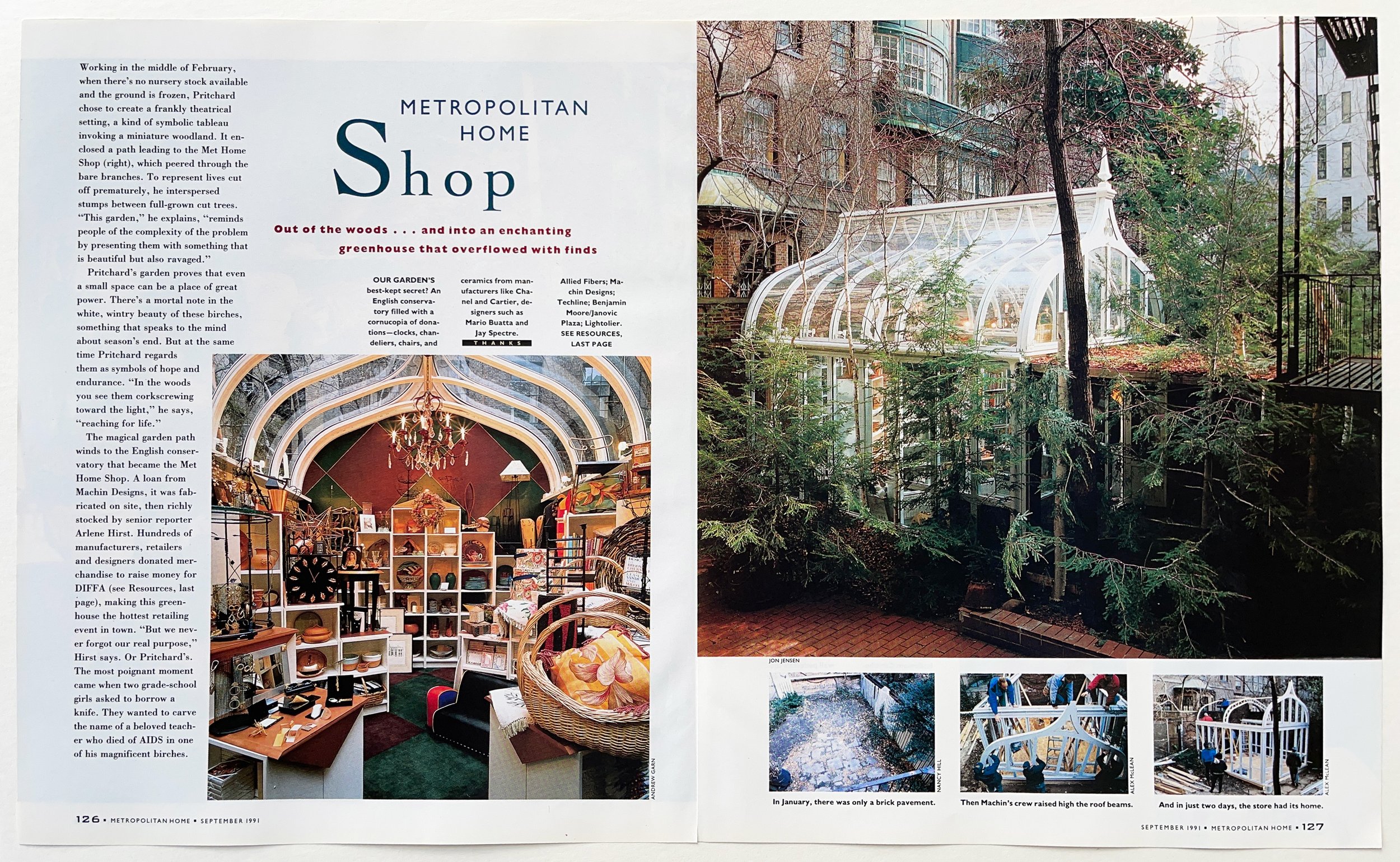

Morris: “The beauty of working for this magazine was that you’re surrounded by talented, caring people. Long hours were no problem if you were lucky enough to be a part of a strong team and believe in their mission. The Met Home staff rose to the AIDS epidemic by raising money and awareness via an ambitious showhouse/gala/magazine project in Manhattan. Our editors collaborated with the brightest architects, interior designers, artists, set designers, and landscape designers to create an eclectic, high-energy design experience in a Manhattan townhouse. Our staff curated a delightful shop with objects vetted by the magazine. We then staged an elaborate gala—orchestrating the event’s design, delicious food by enlisting top chefs, and first-class entertainment. This culminated into a richly detailed special issue that challenged the status quo and raised substantial money and awareness for DIFFA (Design Industries Foundation For AIDS).”

“We were so terrified because this was the early stages of AIDS and we saw it happen among the gay population that were the designers and our readers who were so important to us.”

So when I went to the head of the magazine group and said, “We want to do a special issue, we want to do a showhouse, inviting, not just interior designers, but set designers, and architects, and chefs to do rooms. And we want to have a gala, and we want to invite 1200 people, and have a shop where people can contribute what they made, their lamps, their objects, their whatever. So people, we could raise money that way.”

He said to me, “This is an idea that is doomed to fail. But if you are right, I will eat my words.” And in fact, he did. He wrote on a piece of paper six months later, when it was done, and he put it in his mouth, and chewed it, and swallowed it.

So, not only was it early in the AIDS world, it was something that magazines just didn’t do. You know, you were lucky to get your issues sold, and be able to sell enough copies on the newsstand, and get your paper and printing prices down. And that was the economics of being in the magazine business. But we just felt that we had to do it.

And we kept going back to our same well of people. I remember a young editor [Newell Turner] who came from the magazine program at Ole Miss. He was in graduate school at Ole Miss in journalism. And I was giving a speech down there and I came back and it turned out that one of our assistants had left, and I called up and I said, “Listen, if you really want to come to New York and you want to do this...” And the next year he wound up designing the lady’s room of the Park Avenue Armory so that it could be a place that people would be able to go during the gala. He ultimately went on to become editor of House Beautiful, interestingly, at Hearst.

But everybody was into it together because it was bigger than all of us. And we just, we were terrified. But we went for it.

Don Morris: Yeah, the entire staff was involved.

Dorothy Kalins: Absolutely. The entire staff.

George Gendron: As you’re talking, I’m thinking I could imagine many magazines getting together and thinking, “Well maybe we should donate a page of public service advertising for the cause.” So my response is, Dorothy, I think you had to think bigger at the time. That was huge.

Dorothy Kalins: You had to be a little bit nuts. But we were so terrified, George. Really, we were terrified because this was the early stages of AIDS and we saw it happen among the gay population that were the designers and our readers who were important to us. And it was just, we were very close to it, very early on.

George Gendron: I remember that period vividly. The first person I knew who had actually died of AIDS was my IP attorney up here in Boston — who was also Julia Childs’ — a brilliant, wonderful man, and I was having lunch with him, and he seemed to have a cold. And he had just come back from South America and he said, “Yeah, I picked up a virus down there.” And six months later he was dead. And this chill went through the community up here, when suddenly the gravity of this dawned on people. And yet it took ages and ages. So that was courageous and thrilling what you guys managed to pull off. That became a huge deal in New York.

Dorothy Kalins: It was a huge deal. It was terrifying every single step of the way. I won’t pretend that it wasn’t, because it was totally unplowed territory. But that’s where having a group of people around you who always encourage each other to go for it.

And that’s what I just feel like people who are working remotely and who are not seeing each other every day and who are away. You know, it’s very hard to generate that kind of feeling, both for the work that you do and the larger things that you tackle. It’s very difficult to do.

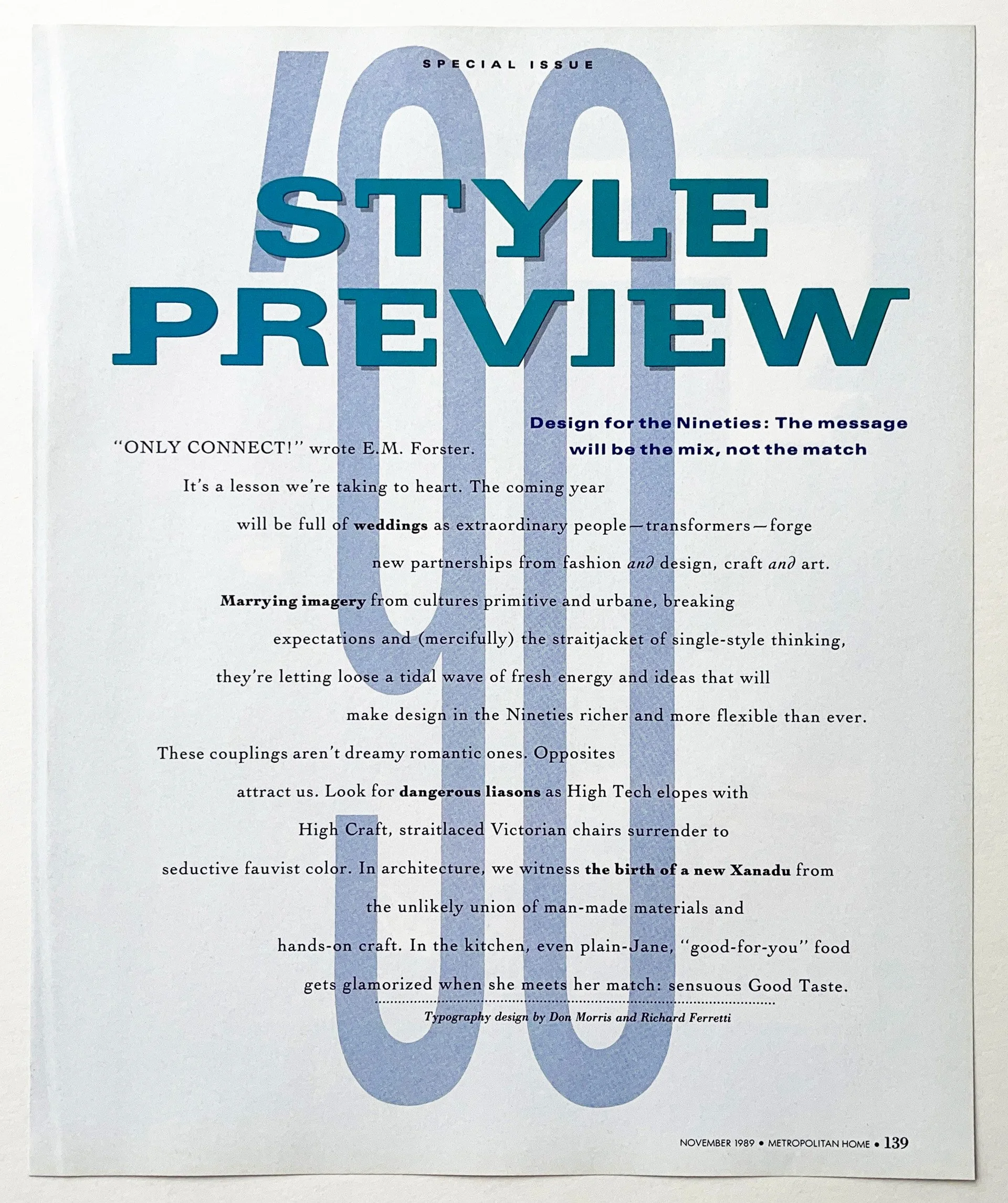

For the Design Preview ’90 issue, art director Richard Ferretti and Morris conceived of two related fonts. With no time to hire a typographer, the multi-talented Ferretti drew each character and then cut-and-pasted every title together for this special issue.

George Gendron: Okay, guys, now it’s time for our Print Is Dead Billion-Dollar Question. And you can answer this individually or collectively, and that is that the two of you are invited to lunch with Laurene Powell Jobs, and she confesses to you that she has always been a print magazine junkie and that she adored Metropolitan Home — although she was very young at the time. And she says to you, “I’d like to fund any magazine idea you would like to launch today. No budget. But I’d like to do my little bit to bring print magazines back to life again.” What would you guys do?

Don Morris: I think it would be something that doesn’t exist only in print. I think you would have to embrace the sort of multi-channel nature of the way that people like to receive things. So I think, you'd, you know, come up with a whole strategy that kind of gets a wide enough audience to matter. Subject-wise…?

Dorothy Kalins: See, I think it’s passed. I do. I think it’s an art form that lived in its time. And I fought it till the very end, but I, I just I wouldn’t launch a print publication right now.

George Gendron: Because it’s not financially viable? Keep in mind, Laurene doesn’t care about that.

Dorothy Kalins: It’s not that. It’s more that how can you be the only important voice in anything anymore? I mean, my last magazine job was the executive editor of Newsweek. And I remember running into Michael Wolff in the park. The writer Michael Wolff, who went on to write three books about Trump in his first three years. And he said, “I’ll bet you $10 million that Newsweek is not around in five years.” And I said, “Oh, Michael, don’t be ridiculous!”

I don’t know. I just believe that we were so lucky to have had the years with magazines that we had. You know, we love doing the books that we do and those are great. I would say, “Go spend it on the children at the border and make sure they have some kind of life, Laurene.” That’s what I would have her do with her money.

George Gendron: Well, I’m going to sound really callous now, because I was about to say that when you get the call from Laurene, say to her, you’ll get back to her, and Pat and I will come up with a bunch of ideas for the two of you that we would love to see you create.

Don Morris: Well, if I picked up the receiver, I think that what I would say is [we should make] a magazine that takes away a lot of the colored opinion to subjects and brings back what journalism is. Because I think that what people don’t really understand, and would be quite relevant, and probably quite fresh, is a magazine, or a news entity, that was really fresh, that showed multiple points of views to a subject, that gave people information and let them choose or let them disseminate.

But really, like the early days of television, where if you had a certain amount of news that was required for you to be able to broadcast, you had to show opposing views. You had to show a couple of views. And I think anything that we could produce now that put different points of view in one place for people to digest and get a little bit more of a balance that they then had to come away and make their own opinion about, would be incredibly useful. You know, to just do something to crack the siloed nature of all these conversations.

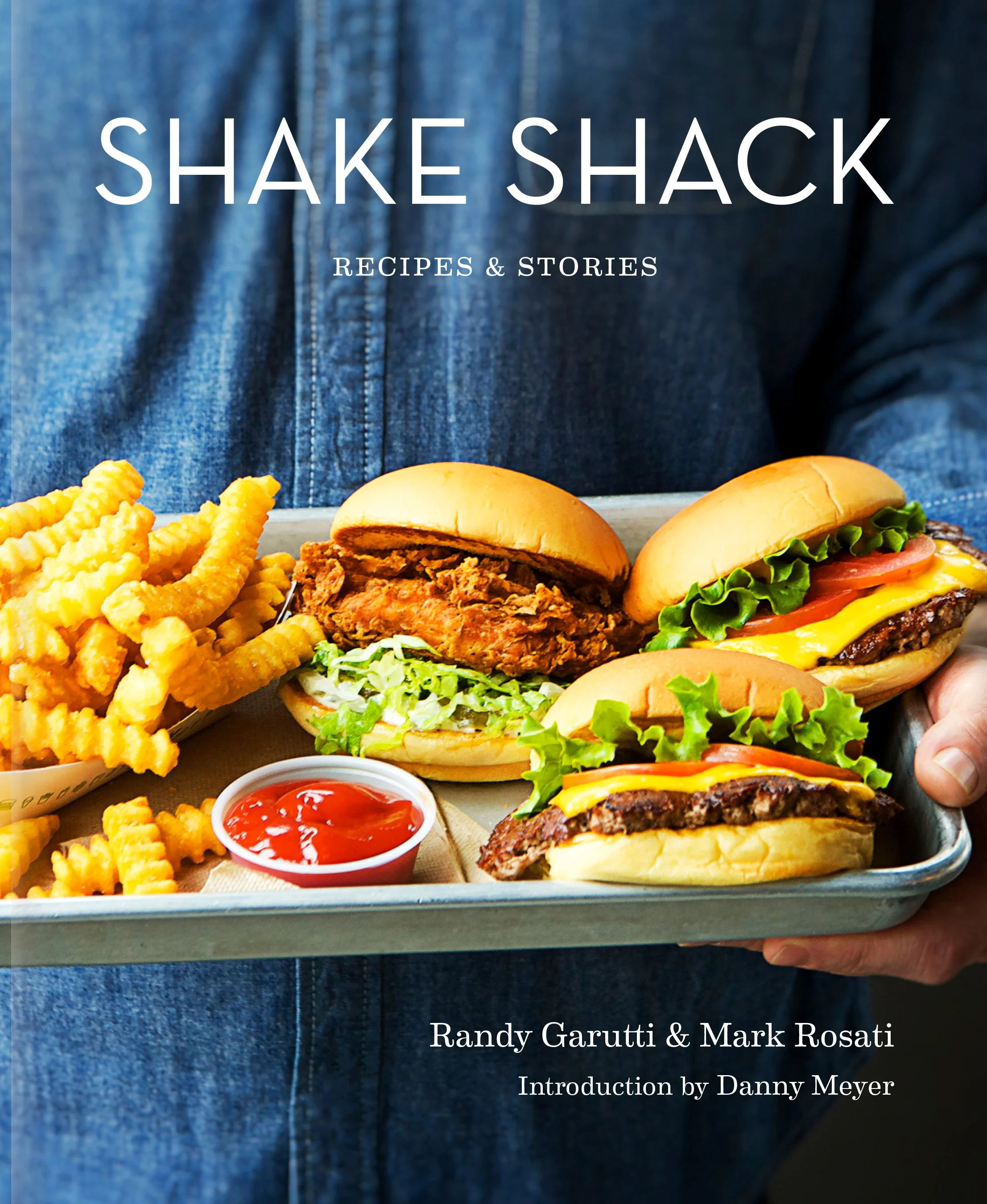

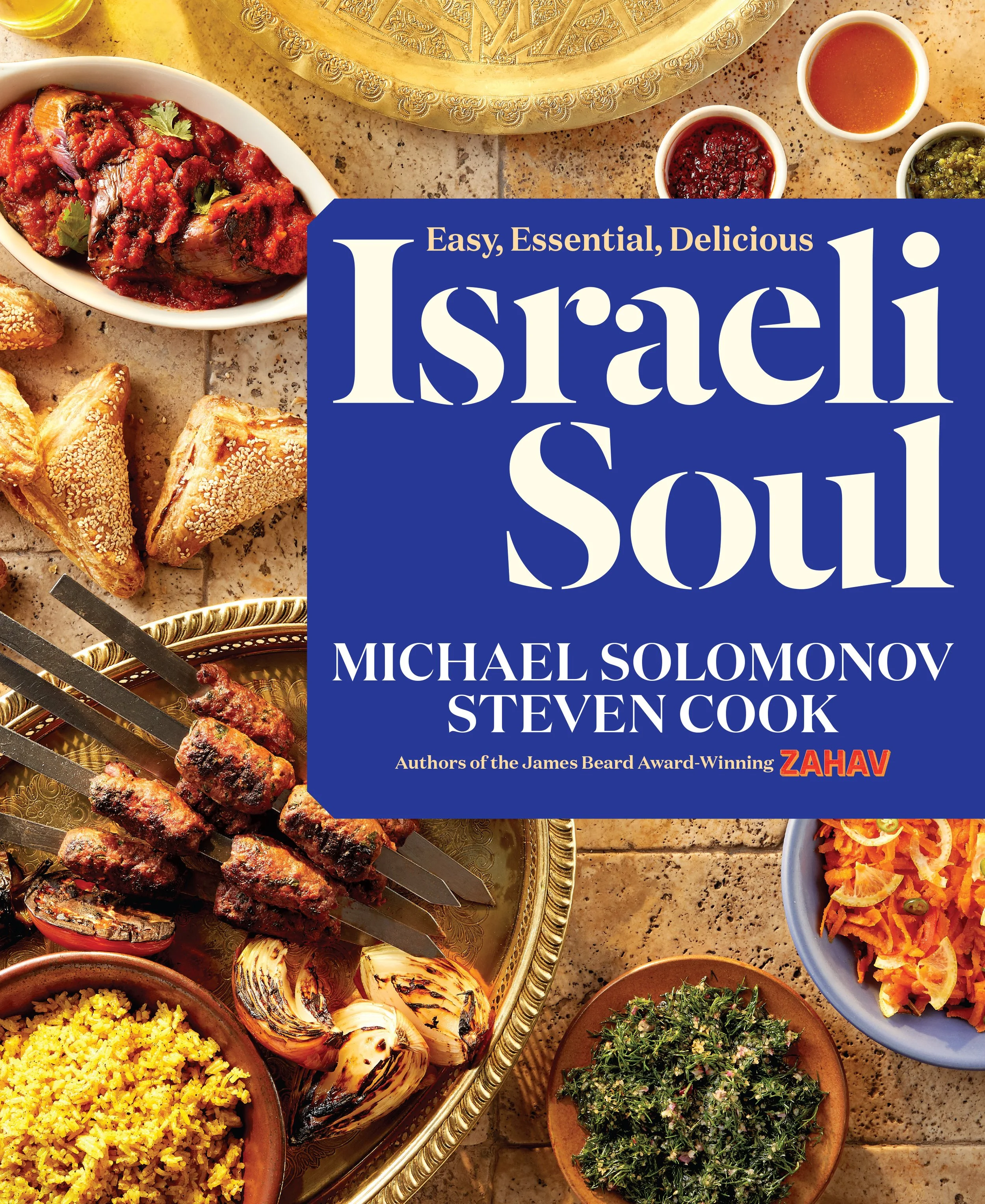

The collaboration that Morris and Kalins began in 1985 remains fruitfully intact to this day. After Met Home was sold to Hachette in 1992, the duo pursued their own paths. Morris launched his eponymous design studio, where he continues to do editorial work with clients including Entertainment Weekly, The Wall Street Journal, and Bloomberg, and expanding into branding and books. In 1993, Kalins became partner and editor-in-chief of Meigher Communications, where she launched Saveur and Garden Design. Between them, they’ve been the recipient of gobs of awards, including multiple National Magazine Awards. In 2018, Kalins was elected to the ASME Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame. Over the last several years, Kalins (now Dorothy Kalins Ink) and Morris have collaborated on several successful book projects (see above), and continue to do so.