Designing Her Life

A conversation with designer, educator, and author Gail Anderson (Rolling Stone, SpotCo, SVA, more).

—

THIS EPISODE WAS MADE POSSIBLE BY AI-AP

Portrait by Paul Davis

It’s impossible to look at Gail Anderson’s body of work and not be reminded of the limitless potential of design.

A traditional biography might pinpoint her education at the School of Visual Arts in the early eighties as her launchpad. But Gail actually kicked off her career much earlier when, as a kid, she created and designed her very own Jackson 5 magazine.

What followed was a series of career moves that also happened to coincide with major inflection points in the history of American graphic design:

After SVA, where she was mentored by Paula Scher and Carin Goldberg, Anderson accepted her first job, at Random House, where Louise Fili was reimagining book cover design.

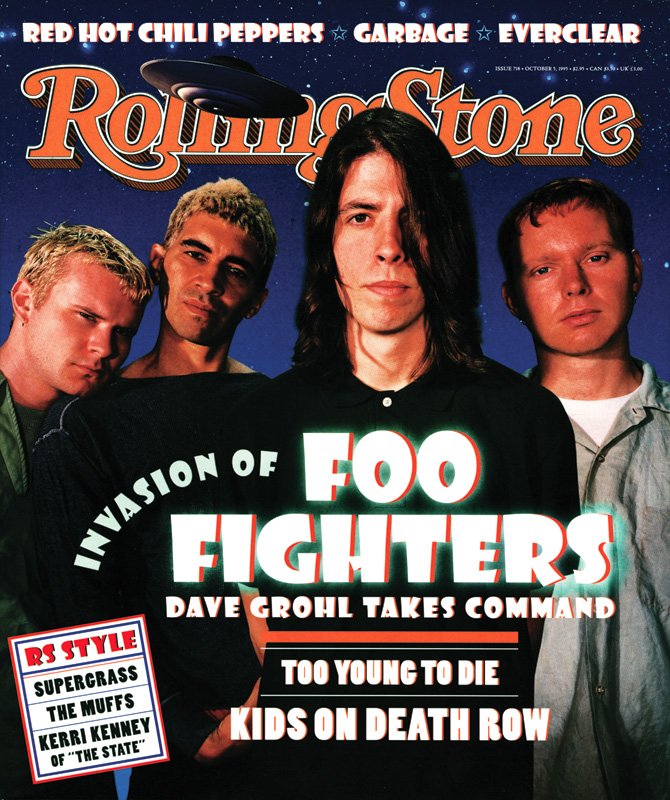

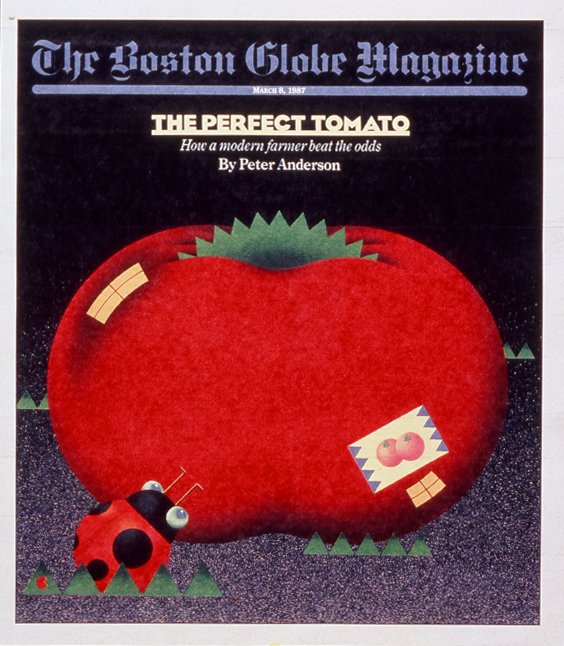

Next, Gail made the move north to join Ronn Campisi and Lynn Staley’s team at The Boston Globe, at a time when the paper, and its internationally-renowned Sunday magazine, filled design award annuals.

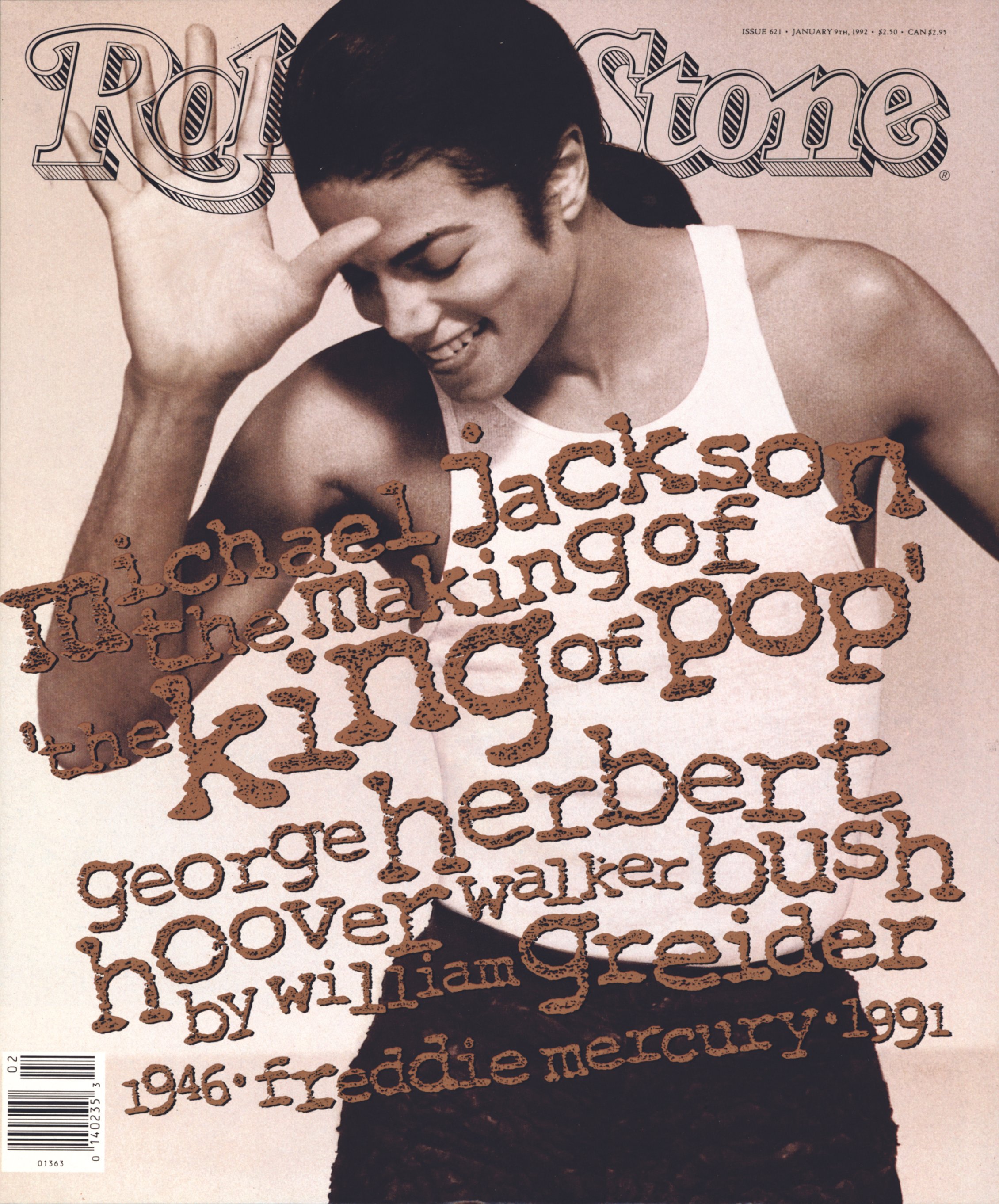

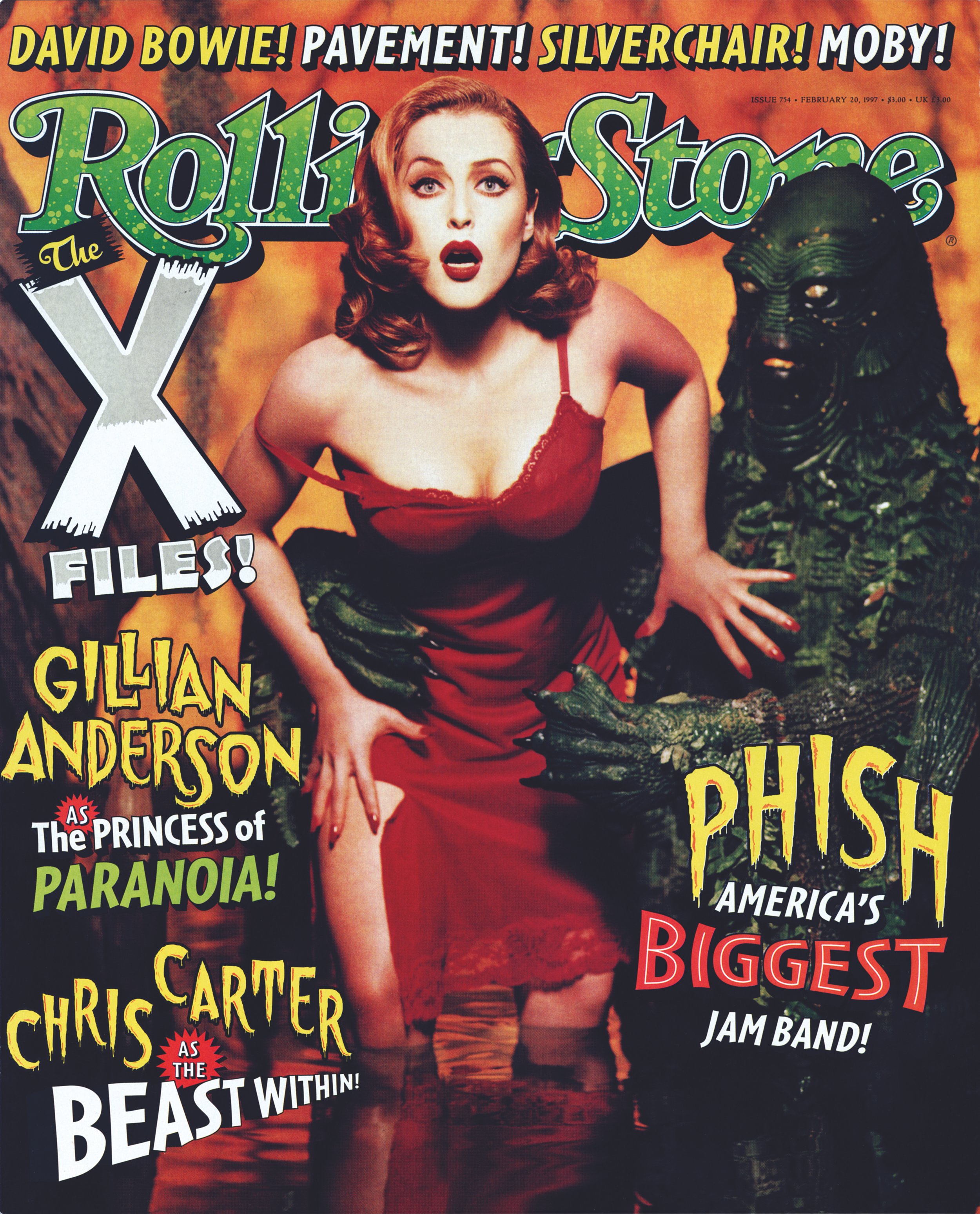

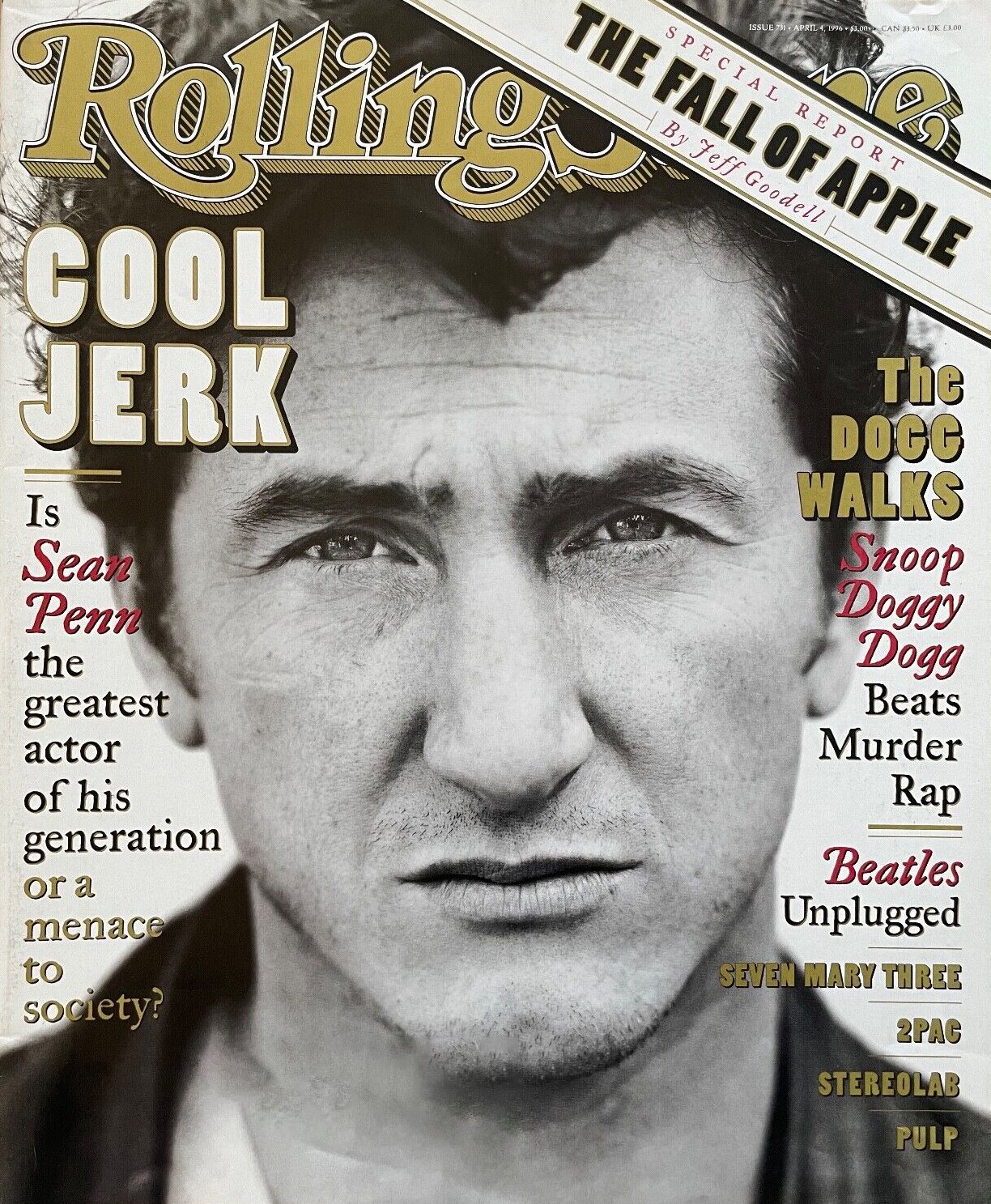

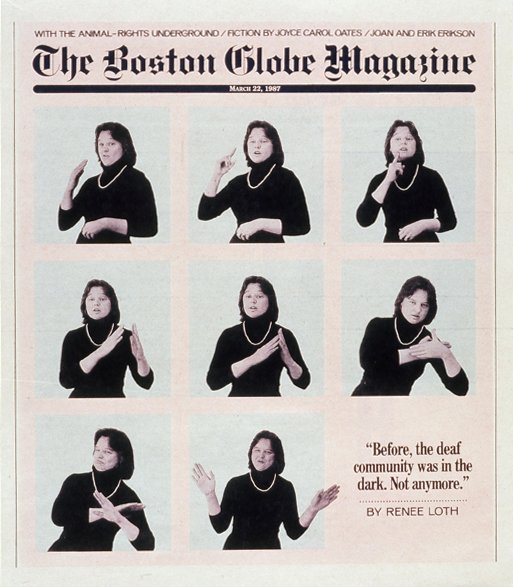

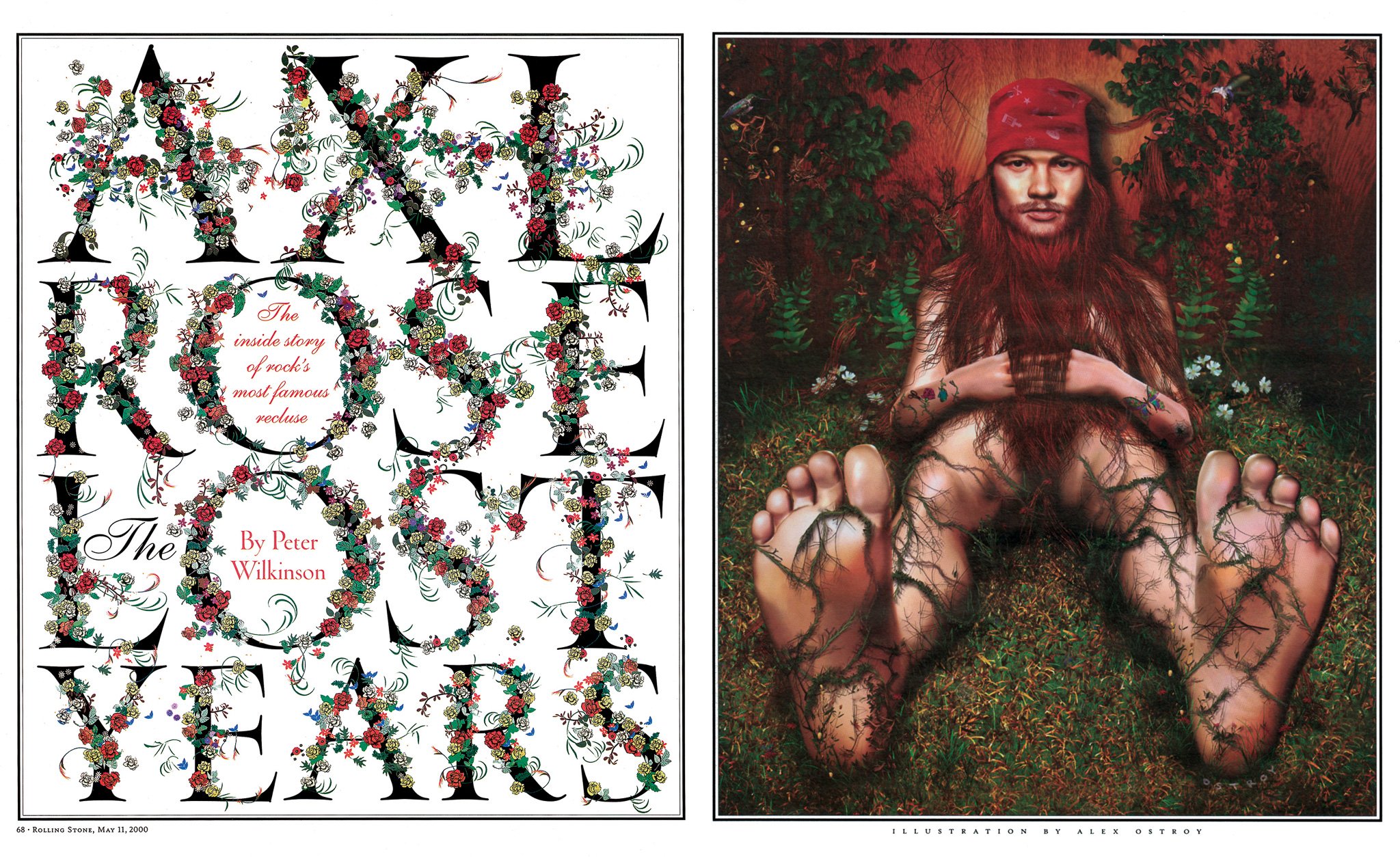

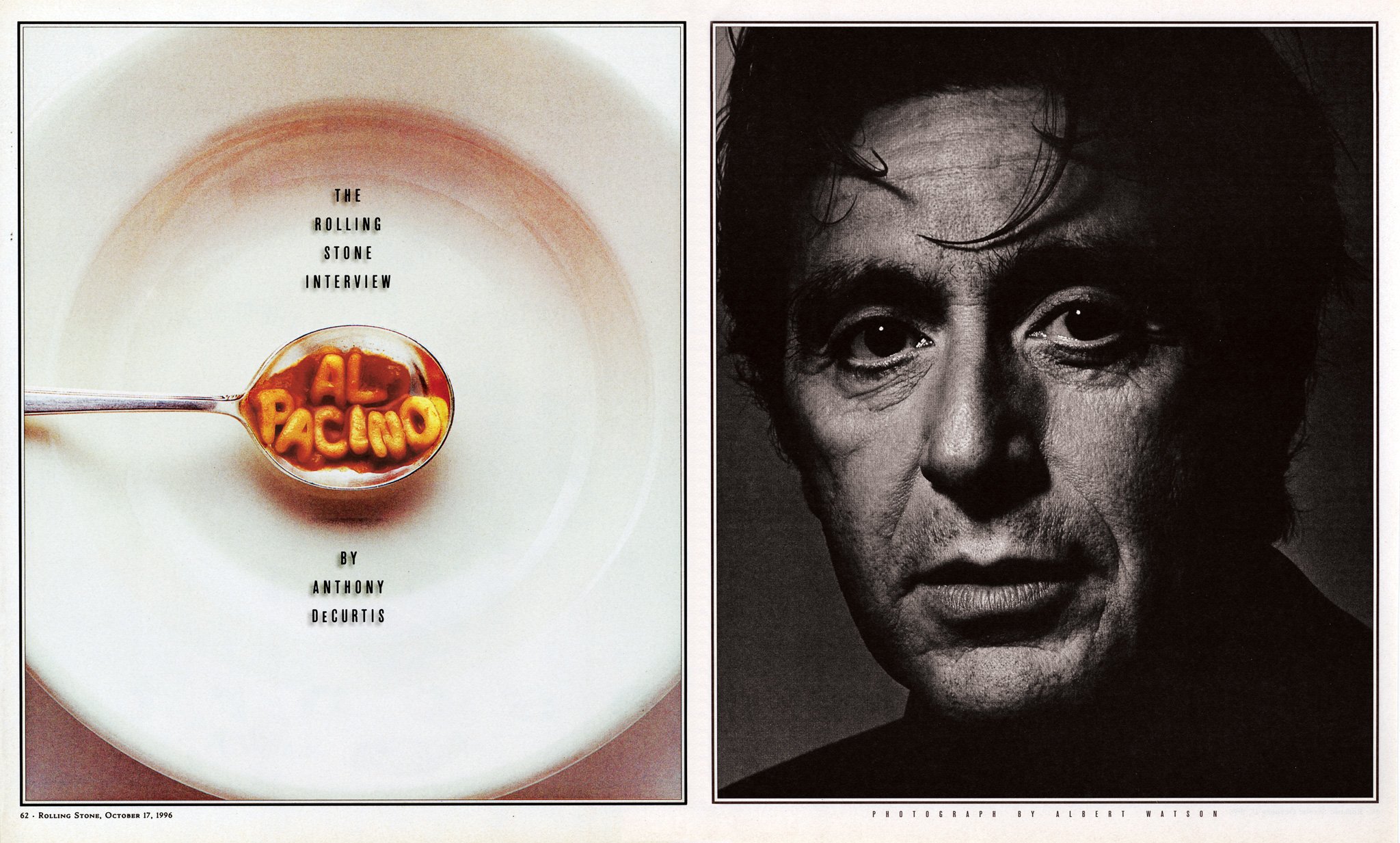

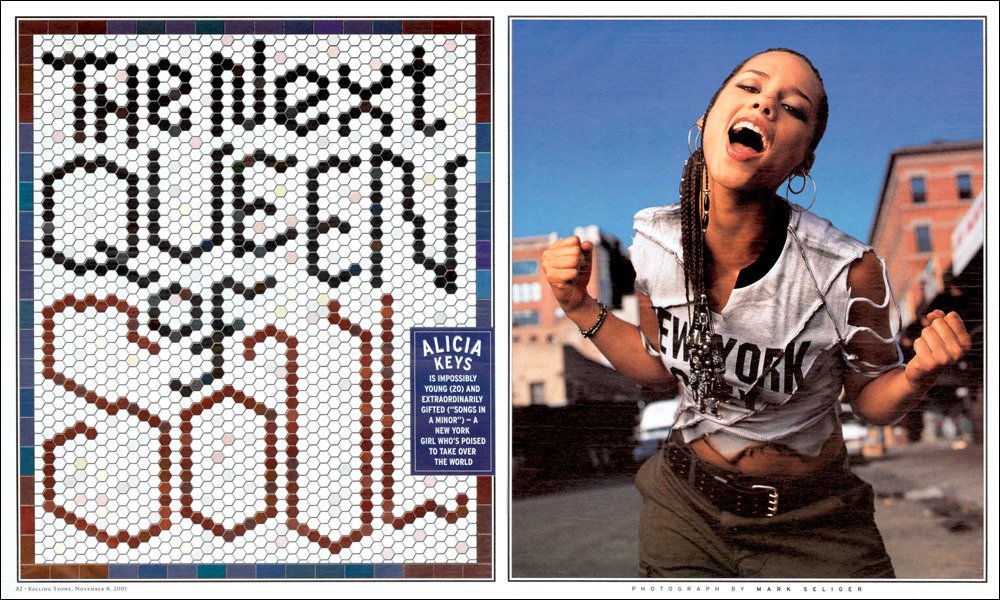

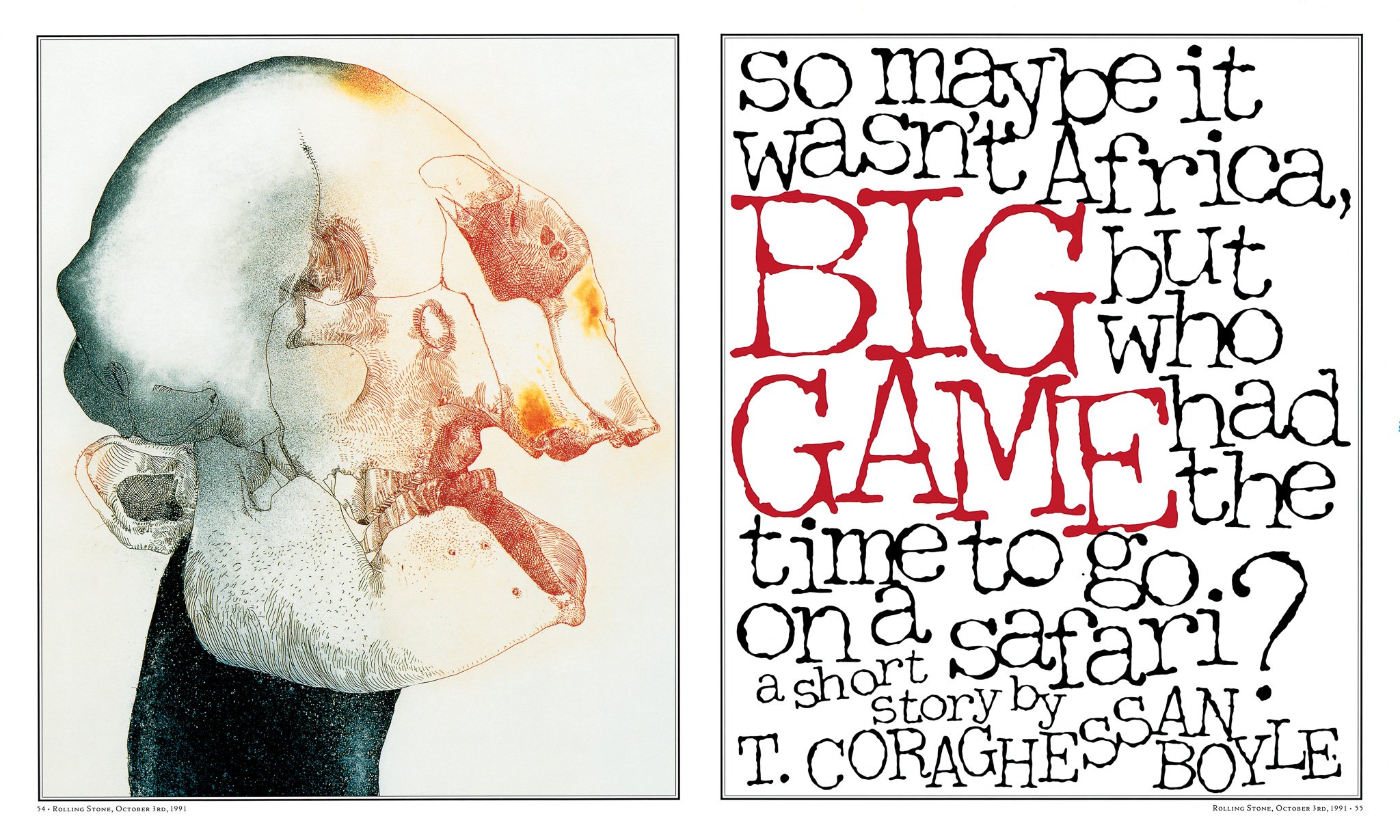

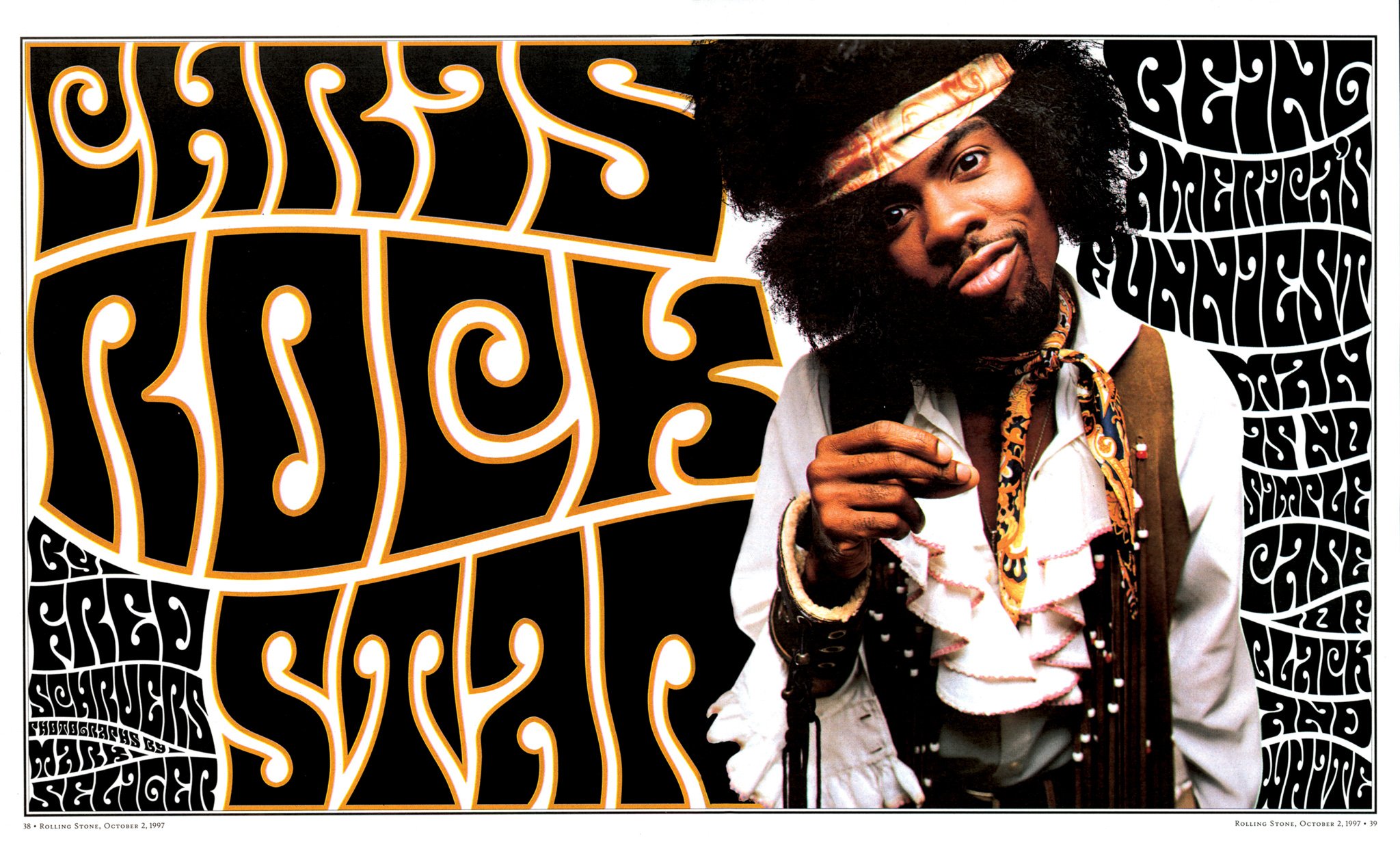

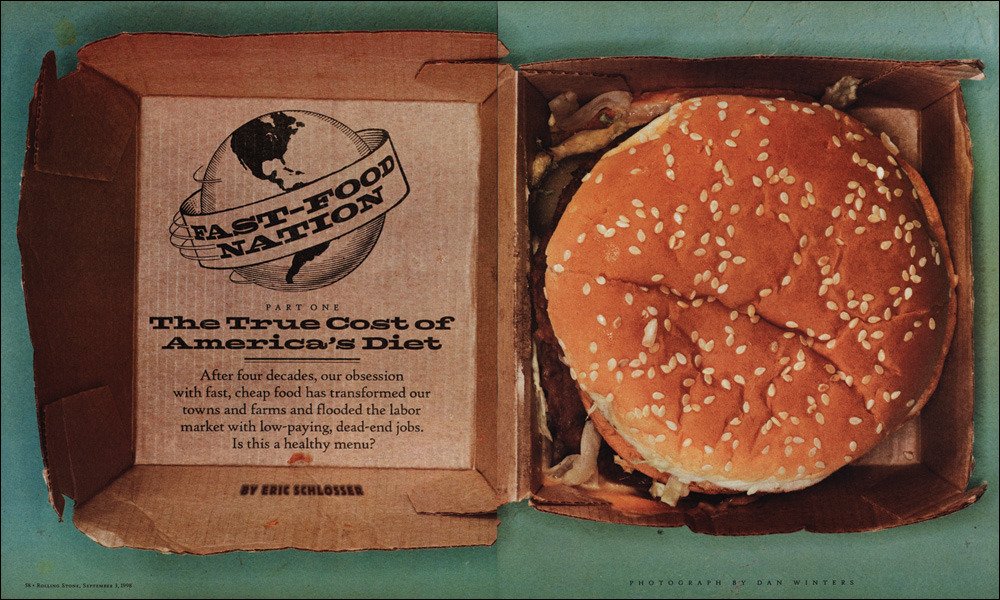

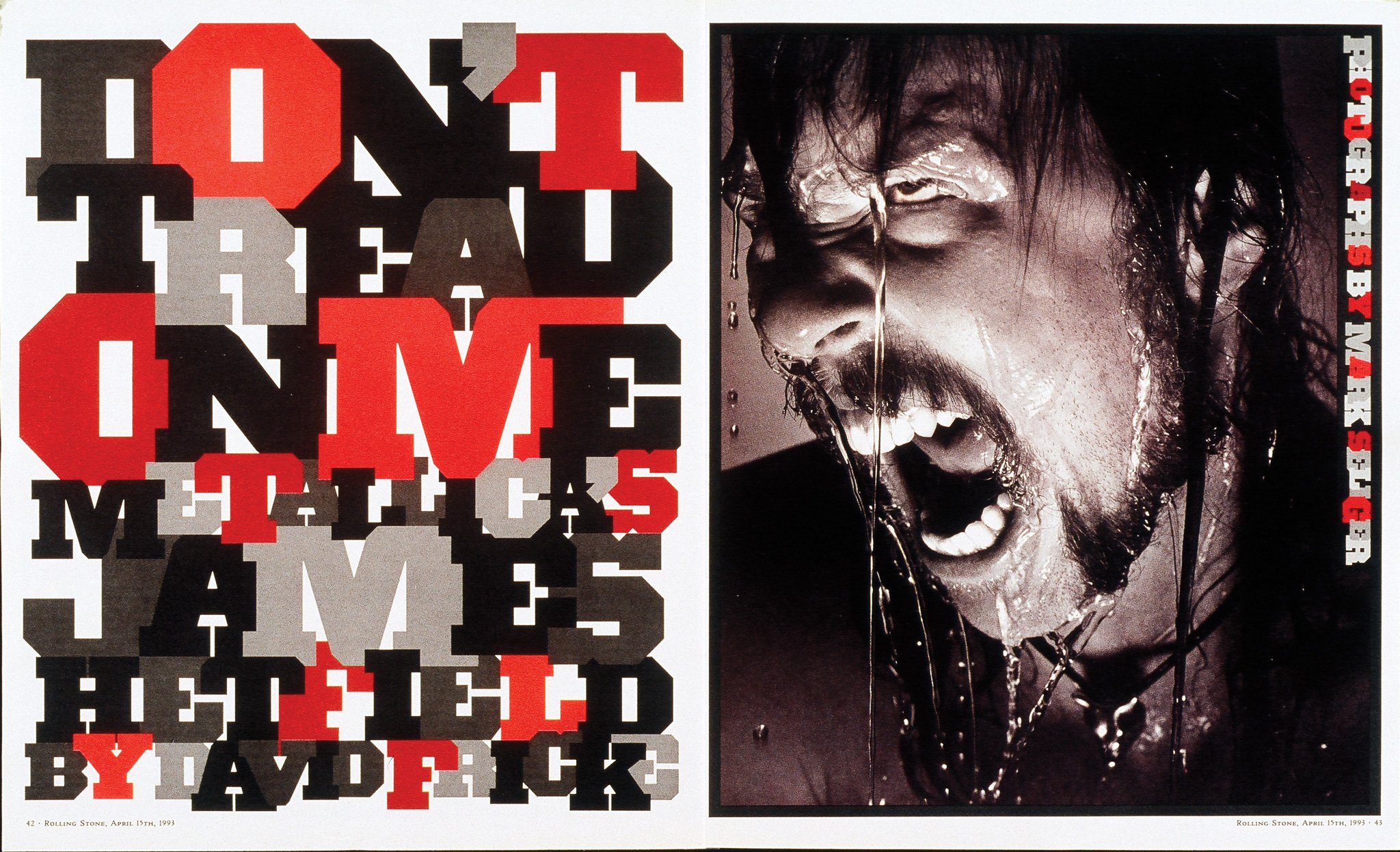

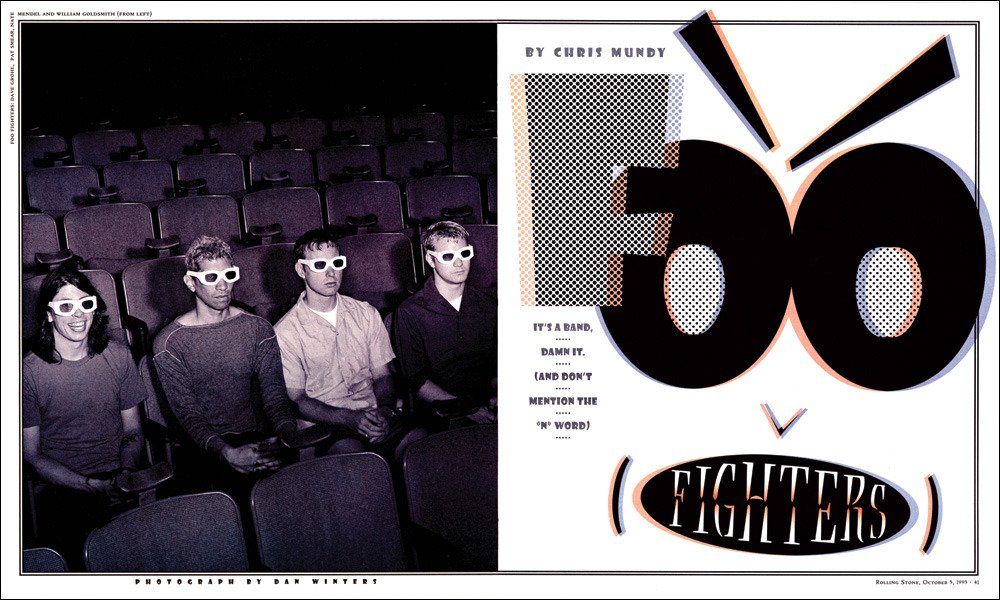

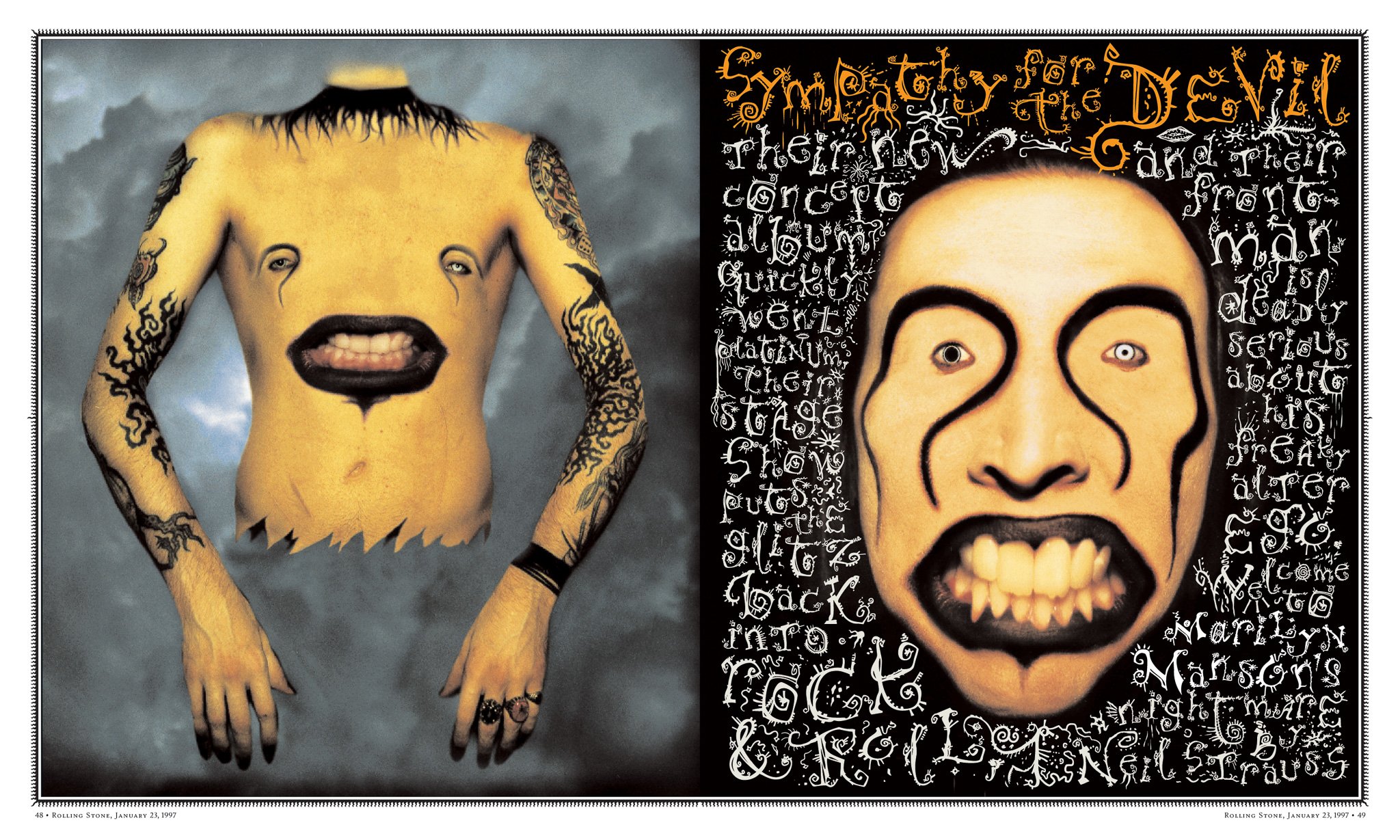

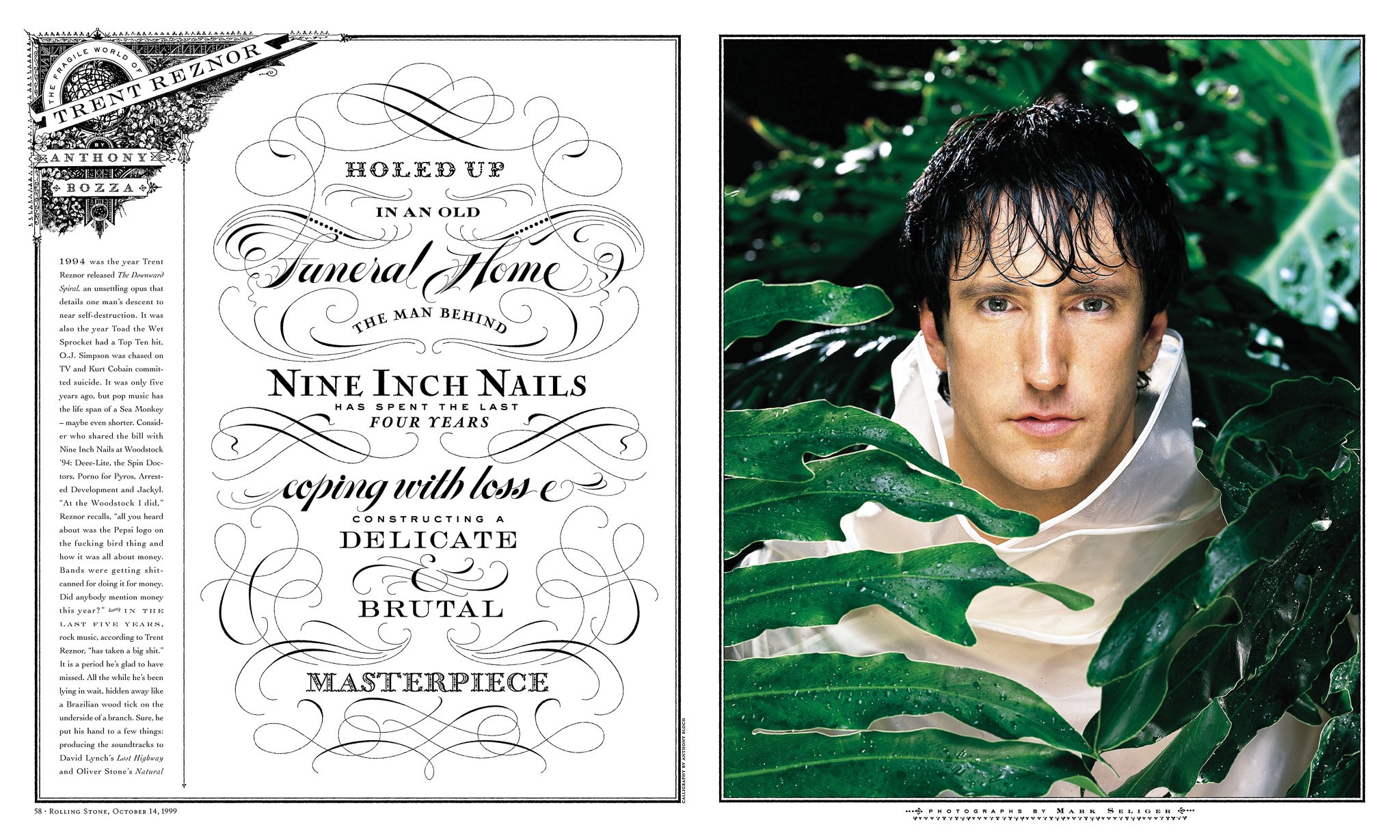

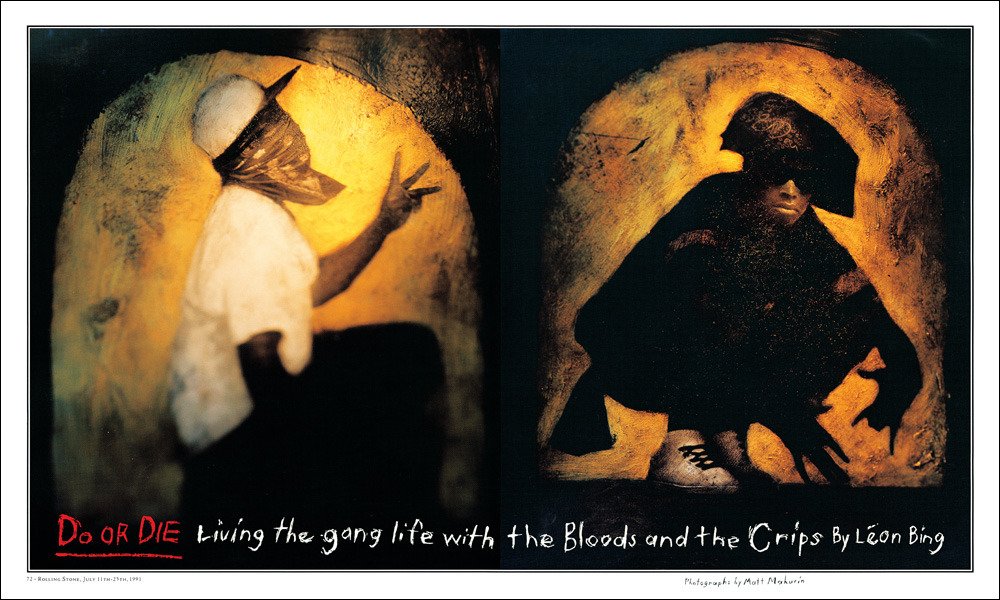

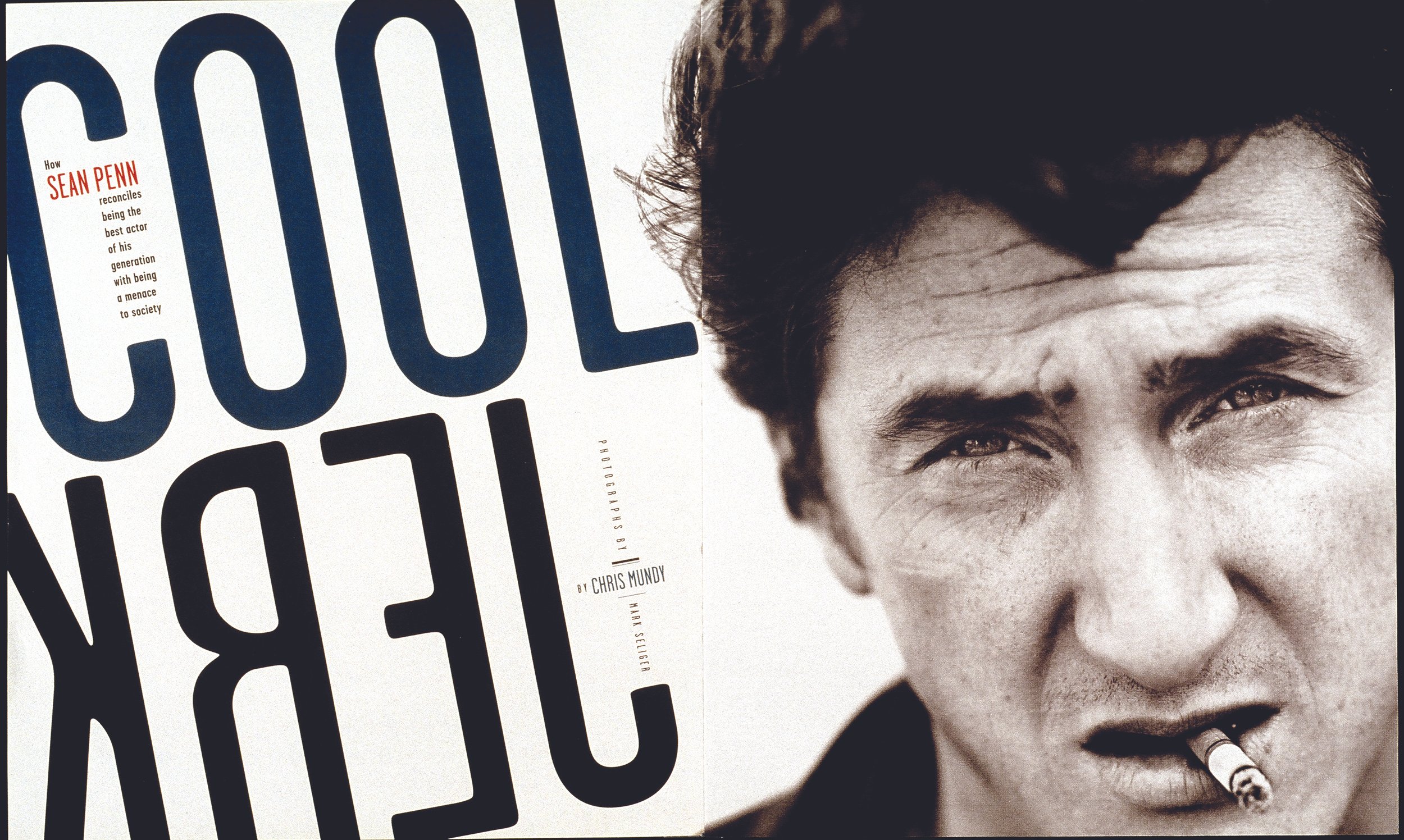

Building on that experience, Anderson was summoned back home to New York to help Rolling Stone’s brand new art director, Fred Woodward. The two would spend the next 14 years showing the rest of us how magazine design is done.

Upon Woodward’s departure for GQ, Anderson exits stage right to join her SVA classmate Drew Hodges at SpotCo, a firm that specializes in work for theater. This, naturally, happens to be the precise moment Broadway was learning new ways to present the magic of the stage to new generations of audiences.

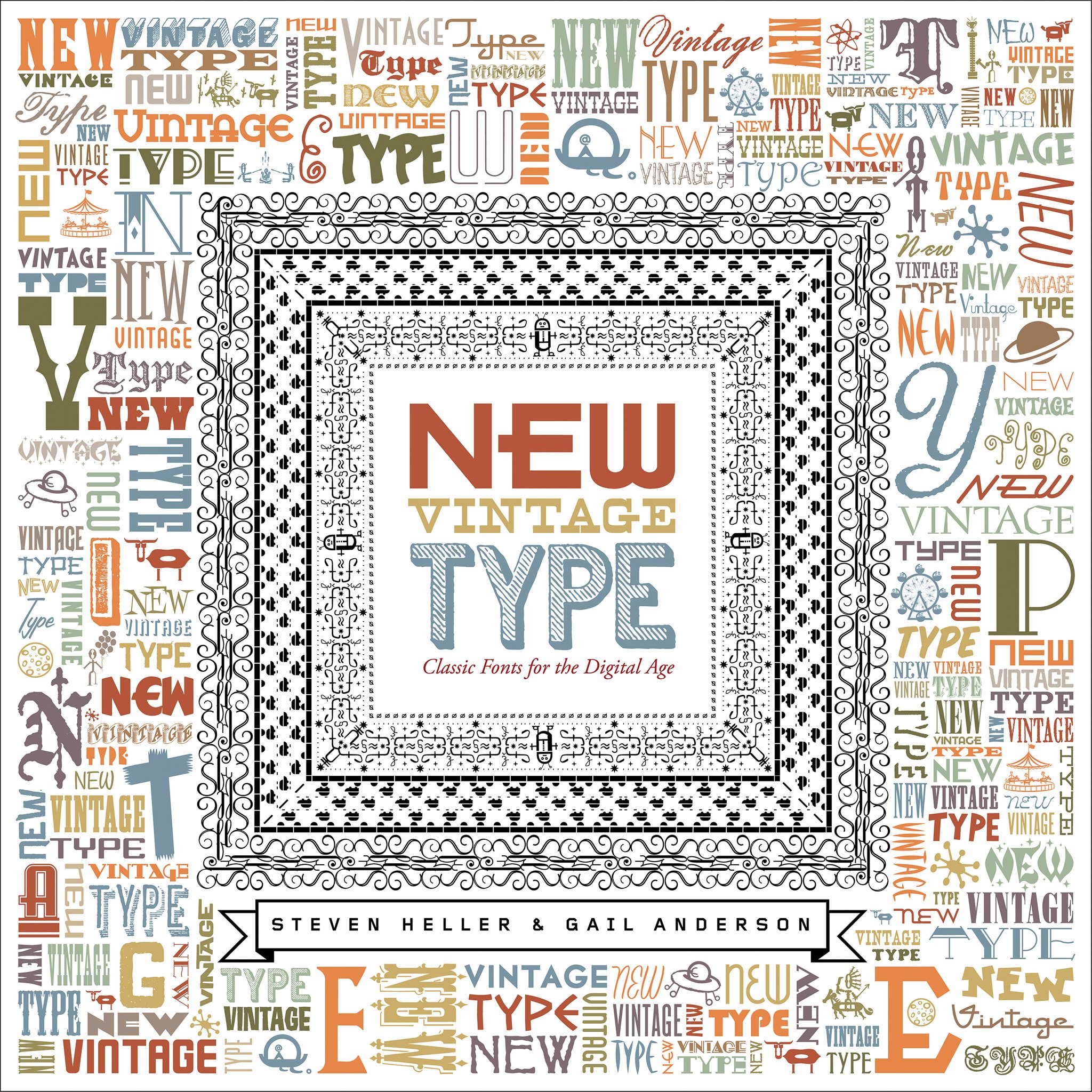

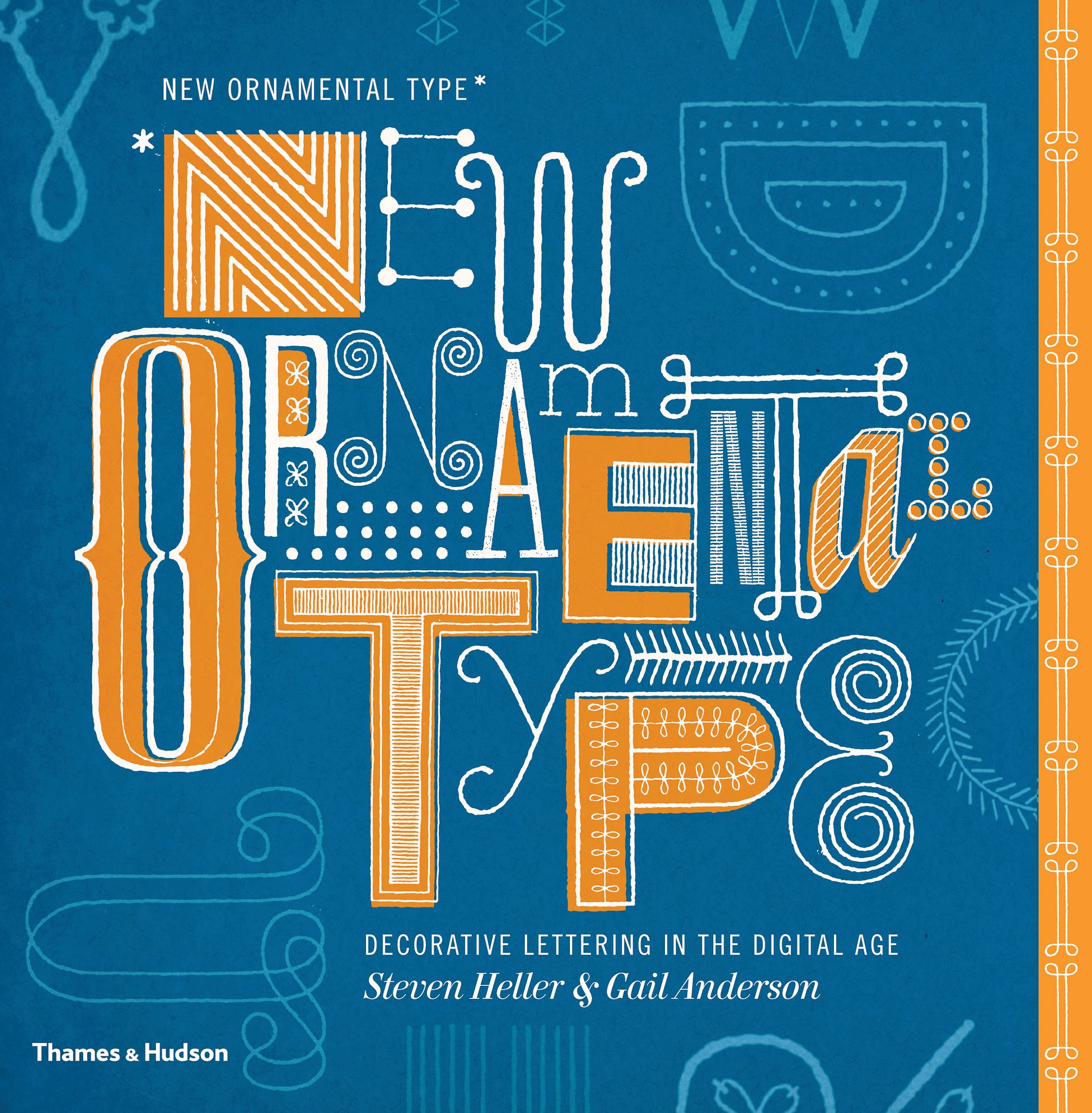

Also, just a quick sidebar to point out that in the middle of all of the above, Gail was collaborating with Steven Heller as he was ramping up his “side gig” as one of the world’s leading design-book authors.

And now, Gail is back at SVA working with aspiring designers, yet again at a moment when everything about the design world is rapidly changing.

It’d be implausible—and wrong—to suggest that Gail Anderson “Forrest Gump’ed” her way through her career. You could call it luck. (She does). But the reality is that Gail has made her own choices, created her own opportunities—“designed” (there we said it) herself a life, all the while bringing to the world what everybody loves about her: her sense of self, her joy for life, her humility, and her standards of excellence.

Patrick Mitchell: Alright, so in all this research I’ve done you come across as a person who just seems like you walked out of the womb fully formed. Which is usually a statement on the kind of family you grew up in, but if you don’t mind, why don’t you tell us a little bit about your mom and dad and your siblings growing up in the Bronx

Gail Anderson: In the Bronx. Yeah, my family’s from Jamaica in the West Indies and came to the Bronx. We were the first family of color on our block and got a lot of resistance to our presence. And I don’t think of my folks as pioneers, but in a way they sort of were. And they rolled with it.

And as kids, my sister and I didn’t realize that something was different. But we kind of kept to ourselves a bit. And I think the neighbors soon realized that we were harmless and that we kept our house as nice as everybody else. My father mowed a little strip of grass out front.

Our next door neighbors—we had a shared driveway—they wouldn’t use the driveway if we were outside. They wouldn’t sit on their back porch, stuff like that. Neighbors across the street, we had alternate side pick up for garbage, and they would put their garbage on our side of the street. And my father would walk it back over and say, “No, tomorrow’s your day, please put your garbage in front of your house.”

And, you know, we grew up not turning our bikes in other people’s driveways and things like that, thinking we were being polite and not really realizing that we just had to sort of be extra careful.

Patrick Mitchell: That can really have a long term effect on a person.

Gail Anderson: It does. It made me feel like I’ve got to work ten times as hard, you know? Sort of “Jamaican with three jobs.” And same for my sister. And sort of stay under the radar and don’t make a fuss and all that. It really sticks with you for your whole life.

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. Yeah. So sad. Were either of your parents in creative fields?

Gail Anderson: No. My father, by trade, was a watchmaker. He learned that from his father, who was a jeweler in Christiana in Jamaica. And my mother, when she started working when they came to New York, she was in a steno pool. And she hated that. And then she had us, and then later was taking classes at a local high school taking steno classes and refreshing her typing and thinking, “Okay, time to get back out there.”

And then ended up working for the Salvation Army store in Mount Vernon near where we grew up in the Bronx. And she was a sales clerk till she retired and they moved to LeisureTowne in New Jersey—“Where Every Day is Sunday!”—and lived out their lives there.

Patrick Mitchell: Alright, well, so watchmaking, you know, I could see how that could catch a girl’s eye. I mean, again, you’ve got all the traits of a thoroughbred designer. And I understand you made your own little magazines as a kid.

Gail Anderson: I did. I wish I still had them! I’ve got everything else and somehow I don’t have those magazines.

Debra Bishop: That’s a shame. Well, maybe you could make one for us.

Patrick Mitchell: And I saw an interview you did with one of your classmates from Cardinal Spellman, and sort of got the impression you might have been that art kid that we all had in school.

Gail Anderson: Oh, I was the art kid. Oh, absolutely. Yeah.

Debra Bishop: Were you the art kid?

Gail Anderson: I was the art kid, yeah. I won the art award when I graduated. Val DiFebo, who’s CEO at Deutsch, she was president of our student body, and we worked for her. I was one of her advisors on the president’s council and yeah, Val’s going off to do great things. She’s the boss.

Patrick Mitchell: So Cardinal Spellman—hotbed of creativity.

Gail Anderson: Yeah. Tom Woodruff, the illustrator went to Spellman, Sonia Sotomayor—an unusual group of people are Spellmanites.

Patrick Mitchell: Amazing.

A page from Anderson’s 8th-grade notebook

Debra Bishop: When I was little I had a thing, I’m still little, but I had a thing for The Monkees. Davy Jones. Peter Tork…

Gail Anderson: …Mike Nesmith.

Debra Bishop: And also this TV show called Bewitched. And now I hear that you had a thing for teen magazines…

Gail Anderson: I still have my teen magazine. I still have my Spec and 16 magazines.

Debra Bishop: … And a group called the Jackson 5?

Gail Anderson: The Jackson 5—yes! My scrapbook is at the Smithsonian now. Held together with Elmer’s glue that’s still held up over these years.

Patrick Mitchell: You get to pick one Jackson 5 member to spend the rest of your life with. Who is it?

Gail Anderson: You know, when I was a kid, it was Michael. And then I was like, yeah, maybe it’s Marlon.

Patrick Mitchell: Marlon’s a little more complicated. A little deeper.

Debra Bishop: I thought Marlon was pretty cute.

Gail Anderson: Yeah. And he’s aged nicely. Got a mustache. He’s alive, so that counts.

Debra Bishop: Gail, was there a eureka moment in your life when you realized that graphic design was the thing that you wanted to do?

Gail Anderson: Well, since you’re my peers, you know that it was called commercial art then and not graphic design. But at high school at Cardinal Spelman there was a book, Careers in the Visual Arts that Dee Ito wrote for SVA. A little black book. And I borrowed the book from our art school library, and I was like, “Huh, this is what I want to do.”

So that book and Paul Davis’ To Be Good Is Not Enough When You Dream of Being Great poster for SVA, that was in my art room at Spellman. I was like, “I’m going to go there. I’m going to do this.”

And years later, meeting Dee Ito, Marshall Arisman’s wife, and being friends with her now in my dotage, I said, “That book changed my life. And that “To Be Good Is Not Enough When You Dream of Being Great” line that you wrote Dee!”

You know? Whew!

“Our editor would always talk about this guy, Fred, who she’d worked with. And she said, ‘You’re very much like him. And you would like him.’”

Anderson (left) with Fred Woodward

Debra Bishop: Wow. You ended up going to SVA. Were your parents supportive of you being a graphic designer? Did they know what that was?

Gail Anderson: No.

Debra Bishop: Commercial art?

Gail Anderson: No. We were first generation, so they just wanted us to go to college. In New York, in commuting distance. And I wanted to go to an art high school, and they said, “No. Get a well rounded education.”

And when I said I wanted to go to SVA, [they said] “Are you sure? Is it a college?” And it counted as college, and I went. And I don’t even know if I visited the school but I certainly know they didn’t. I don’t think they even knew where it was. They came to graduation and that was about it.

Debra Bishop: Well, it was money well spent and clearly set you off on the right track. During your years at SVA in the eighties, let’s talk about the women who were in graphic design at that time. Some of them were your teachers and your mentors. Among them: Paula Scher, Carin Goldberg, and Louise Fili. What made them so influential to you—and really to everybody?

Gail Anderson: I didn’t meet Louise until I started working at Random House. But that was, you know, a minute after school. Paula and Carin, of course, were our teachers and the fact that they were women, first of all, and they were kind of sassy, and bold, and cool. And the work that they were doing, we all copied it and we all thought it was great. And, it was well, “If they can do this then we can all do this too!”

Debra Bishop: Absolutely. [They were] women who were cool. I don’t think I knew too many. They were hugely influential in their inspirations. They worked for record companies and were inspired by the history of graphic design, which I think is very important to you as well, in terms of your style and what you like.

Gail Anderson: Yeah. I feel like I inherited that from all of them, and certainly from Louise, when I got to know her at Random House and the books that I looked at on her shelf, everything that Paula had, just being in Carin’s orbit—these women knew history. And we weren’t taking the history of graphic design or anything like that in school.

We were taking European Painting and World Art kind of stuff. And so this was, oh my goodness, getting Print magazine and Communication Arts and Upper & Lower Case—those were our Bibles then. And these were expensive magazines, so you held onto them. And the annuals!

Richard Wilde in his visual literacy class gave us the Art Directors Club Annual. I still have mine from 1980 or ’82 that he gave us. And there was no internet, so you’d just peruse those annuals. And stole from them. Oh my goodness. So much good stuff. And going to Rizzoli and The Strand—oh, God!

Debra Bishop: I think we all became bookaholics. I was obsessed. And now I have all these books and I don’t know what to do with them!

Gail Anderson: Yep. And I still buy books, and more books, and they are stacked up there. I bring them into work now and scan stuff and share it with students and Jim Biber has promised Carin Goldberg’s design books to the school for making a Carin Goldberg Library for faculty. And I’ve been buying. Some contemporary books to add to that.

And there’s such value in them. I give books to the sophomores now as in my class and they’re like, “What?” And some of them leave them.

Like, “You don’t want this?”

“It’s too heavy.”

“Oh, it’s too heavy.” The world’s changed.

Patrick Mitchell: All right, I have a non sequitur here, but I read this and I just can’t leave it alone. I’m sure it must have been a real conundrum for you when you were at a fork in the road of, “Which career do I pursue?” You did not pursue the nurse’s aid job.

Gail Anderson: Nurse’s aid! Oh my god.

Patrick Mitchell: The wrapping of the dead bodies.

Gail Anderson: The wrapping of the bodies!

Debra Bishop: I had no idea!

Gail Anderson: My parents, God rest their souls, how could you let your daughter—a teenager—be wrapping bodies as a part-time job? But I made $6.35 an hour up to when I was leaving, $7 and change an hour. Minimum wage was $2.65, so I was, you know, banking bucks there. But I was wrapping dead bodies!

Patrick Mitchell: If that was me I’d still be washing my hands every five minutes—to this day.

Gail Anderson: There was no Purell back then. But I knew from that experience, those years from junior year in high school right to the end of college, I am never going to work that hard again. Physical labor. I enjoyed what I was doing in school. I would sit in the break room and do my work and people would come in and say, “Yeah, you study hard and get out of here.” And, “Go out there.” And all that sort of stuff. It was very inspirational. I was like, “I am exhausted.” And I’ve got varicose veins at, like, 16 from doing this work—lifting people up, and toilets, and all that.

Patrick Mitchell: All right. Well, so you’re a lifelong New Yorker. You were born and raised there. You went to school there. You’ve lived there almost forever.

Gail Anderson: Almost forever. Yeah.

Anderson launched her magazine design career at The Boston Globe Magazine in 1985.

Patrick Mitchell: I want to talk about Boston. You went to work at the Globe, The Boston Globe, in 1985. Can you talk about what it was that drew you here? Let me preface that by saying the Globe was kind of a design “thing” back then.

I’ve been looking at a lot of old design annuals and the work Ronn Campisi was doing at The Globe Magazine was super influential. And so that’s what started it. But then, you know, all of these people that I’m about to name passed through the doors around the time you were there: Ronn Campisi, obviously, Lynn Staley, you, Richard Baker, Terry Koppel, Lucy Bartholomay, and others I maybe don’t remember. But I’d love to hear what drew you to Boston and what that experience was like.

Gail Anderson: I wanted to work in a magazine when I was in school and ended up at Random House as my first job and was really enjoying it.

And Terry Koppel got in touch. And he said there was a job in Boston, that Ronn was looking for someone, and he told me about the Globe. I knew of his lineage there, and I thought, “All right. Yeah, let me just meet them.” And I went up and I thought, “Okay, I’ll do this for a few years.”

It’s an opportunity to work at a magazine. I thought a Sunday magazine was going to be really fast paced, where book publishing was very slow. And I’m going to learn a lot quickly. And on Terry’s recommendation, and Paula’s, I moved up there for a couple of years and worked with Richard [Baker], and Rena Sokolow, and Lucy Bartholomay, and Katie Aldrich and, my goodness, so many wonderful people. The nicest people you could imagine.

At that point in my life, it felt like family. And I had a wonderful roommate, and I had a car, and we lived in a good-sized apartment in Somerville, in a triple decker, on the top floor. And it’s, like, a wooden house. And I think Lucy and I paid $365 total. It was nothing.

Patrick Mitchell: We’ve all worked on Sunday magazine-type things, and it is accelerated. In two years you can knock out a hundred magazines. But looking back, after that experience, it seemed like you came out of school open to any kind of future career, but this Globe thing must have sort of pushed you in a certain direction.

Gail Anderson: I loved assigning illustrations, and I loved the pace, and what I was learning being away from home, and exploring a new state and area. New friends. It was really exciting. And working for Lynn Staley on the Sunday magazine was life changing. And I only sort of dipped my toe on the idea of coming back to New York because our editor, Ande Zellman, would always talk about this guy, Fred [Woodward], who she worked with, I think, at D. And he was doing Texas Monthly, and I’d look at that and say, “This is really cool.”

Patrick Mitchell: He was doing a Sunday magazine at the time [Westward at the Dallas Times Herald].

Gail Anderson: Yeah. He had done a Sunday magazine as well. And she said, “You’re very much like him and you would like him.” And then he was doing Regardie’s. And I subscribed to that and I was like, “Oh, this guy does great stuff.”

And one day I saw the George Harrison cover of Rolling Stone. And it was like, “Well, this looks different.” And I was like, “It’s that guy again. It’s Ande’s friend, Fred.” And I said, “I’m going to reach out to him and see if he’ll look at my portfolio.” And I had slides made—35mm slides—of all my raggedy Globe stuff, and sent, like, pages of it. I had so much work because I’d done so much in a couple of years. And I can’t believe I did that!

And I called one evening and nobody else was there and [Fred] picked up the phone, because he was young and naïve enough, and he was like, “Hello?” At night! And he’s like, “This is Fred.”

And I explained I was Ande Zellman’s friend, blah, blah, blah. And he’s like, “Well, you know, you can send me some work, and I happened to be looking for someone.” I was like, “Okay, thank you very much.”

And I thought, “Well, maybe everybody picks up the phone when you call them like that.” And I sent work. And he called. And I hadn’t said anything to Lynn, to anybody. And when Fred called, our secretary picked up and she said, “Fred Woodward’s on the phone for you.”

And I was like, “Huh?” And I’m like, “Fred? What? For me?”

So that was that. And I flew down after work and met him and was so wowed. And he was so lovely—a big giant smile, and his fancy clothes, and all that hair. And he didn’t hire me, but he kind of left me hanging for quite a long time.

And of course I assumed, while I was waiting, that he was going to hire me. So I was like wrecked with, you know, “What am I going to do?” And meanwhile, nobody’s calling me. But I’ve kind of figured all this out, and up all night. And so finally, I’m like, “I’m calling him.”

And finally, I just sort of gave up, and I was going on vacation with my roommate and her family, and he called my house, and said, “Well, you know, I had to go with somebody else who’s more experienced because I’m still new and I can’t take on somebody junior.” I’m like out the door going to Maine. I was like, “All right, good luck. Bye.”

I had given up at that point. I was like, “Oh, that was nice of him to call me back, but I’m going on vacation now.” And I didn’t give it any more thought. Joined the gym. I’m going to change my life. And he calls a couple months later, he says, “Well, things have changed.”

And he’s just such a gentleman that he called Ande—he called the editor and said, “I’m going to call her. Is that okay?” A thing that nobody would do now. So everybody else knew but me.

Debra Bishop: Like a marriage proposal...

Gail Anderson: That was his friend. And that was the right thing to do, you know? It was probably to find out, like, “Is she a freak? Should I not do this?” And Lynn, she’s not even there. Her husband took her to London for her 40th birthday. I’m like, accepting this job…

Debra Bishop: … And you were so close to Lynn.

Gail Anderson: Oh my God. I called her that Sunday so that she wouldn’t find out from anybody else. And she’s just like, “What? I’ll talk to you on Monday. Bye.”

Patrick Mitchell: Well, it was very kind of you to give Fred a couple months to...

Gail Anderson: ... change his mind.

Patrick Mitchell: No, to catch that Gail Anderson wave.

Gail Anderson: So then I get there and he has no place for me to sit! I spent the first couple months in his office with him because there was somebody freelancing, who was my old roommate from school, and she wasn’t going anywhere. So I was like, “Where am I going to sit?”

And he was like, “You can sit with me.”

I was like, “Ohhh.” We were like two strangers making small talk for months.

Patrick Mitchell: Who was in the art department then?

Gail Anderson: Joele Cuyler, Karen Simpson, me. It was the three of us and Fred.

Patrick Mitchell: And if I recall my Fred timeline correctly, this was ’88, ’89?

Gail Anderson: I started there in 1987. I think. Yeah.

“I’d been [at Rolling Stone] for 14 years and I was done. I knew that I had to do something totally different, that I didn’t have another magazine in me.”

Patrick Mitchell: Really at the very beginning. Rolling Stone was just, my God, you know, a once-in-a-lifetime event. Really for all of us. For people like both of you who were part of it and for all of us watching from a distance. I just would love to step back and hear you both talk about those days, because that’s really just, I mean, it was a moment in magazine history that needs to be preserved.

Debra Bishop: What can we talk about?

Gail Anderson: We were working so hard, Deb, that we didn’t even realize that it was a moment in history.

Debra Bishop: One of the things I remember the most—clearly I learned so much—it was my first editorial job. Everything was done by hand. Or on the copier. Do you remember that?

Gail Anderson: Oh yes.

Debra Bishop: Until, of course, we did have to switch to computers. For me it was sort of, like, in the middle somewhere. For you it was probably in the beginning. But what do we miss most about the pre-computer days?

Gail Anderson: You really thought about your decisions. You thought about your letter spacing. You thought about the typefaces you were getting “Reverend Jim” to set on the typositor. When we were still at 745 Fifth Avenue, you went up and down the stairs to make copies, to try to get a degraded copy of something or to blow something up five percent, 15 percent.

Debra Bishop: Yeah. For the younger listeners, it was coveted to have that sort of “worn” type look. And the way we used to do it was on the Xerox machine, our copier machine. And we would actually just stick it down on our mechanical board. Speaking of mechanicals...

Gail Anderson: I had some of the mechanicals when I left. Again, because I had everything. And I donated them to the library at school. And some of them were still hanging together. And they show them to students. And they’re like, “What?”

Debra Bishop: One of the things that I remember about Fred, who I enjoyed working with so much, and have so much respect for, as well as Gail, was he would come up to you very gingerly with a photo or an illustration, as though it was like his only child and hand it to you as though to say, “This is precious. Now go away and design.”

Gail Anderson: Yeah.

Debra Bishop: But at the same time, I felt Fred was very generous with his assignments. Once he gave you an assignment, it was yours. And you had to get final approval. But we would have, what, three days to conceive a spread and then three days to execute it?

Gail Anderson: Yeah. While you were working on the departments. So it wasn’t like you were just laser-focused on the feature.

Patrick Mitchell: Was Fred assigning these illustrations?

Debra Bishop: Gail was assigning a lot of them.

Gail Anderson: That I came equipped to do from the Globe, because I assigned so much art there with Lynn, and I had a good sense of who was out there at the time. And we’d look at American Illustration and the Society of Illustrators Annual, and we got all those samples in the mail and had them pinned up on the walls. I really enjoyed that. And I was sort of managing deadlines and other stuff. So I had administrative stuff to do and probably a little less design, at times, to my liking. I wish I could have done even more.

But I really enjoyed working with the artists. And I was always on the phone, and you made these wonderful friendships, these phone friendships that I can’t imagine exist now. And getting the art, getting the FedEx package or the messenger package and opening it gently opening the piece. Oh my goodness! The piece of art. Wow! Amazing.

Patrick Mitchell: I want to say this as gently as possible because you worked with genius illustrators who probably needed very little direction.

Gail Anderson: I worked with genius illustrators, yes.

Patrick Mitchell: And you gave them very little direction?

Gail Anderson: And the editors were appreciative and into it and we, maybe, talked about sketches a little bit, but it was sort of our show. And that was the genius of Fred—that Fred was a journalist, and Fred was an editor. And so he was a peer.

And we all learned that and took that into our careers, later, that we weren’t “subservient.” We were equals, and we had opinions, and we had questions. And that came from Fred. Writing headlines, just being really involved. And, you know, Deb’s made a whole career of being a collaborator in magazines.

So yeah, that was Fred. For me that was Lynn Staley at the Globe, the same kind of like, “Why don’t we do this?” And it was never, “This one’s in charge.” We’re just making it.

Patrick Mitchell: Remember AIGA Graphic Arts Weekend? You would get studio visits with art directors. It was usually on a Saturday and a Sunday and you would pay a fee to come to New York, and you’d get three studio visits over two days. And my first studio visit was to see Fred.

So I came to the Rolling Stone office, and he gave me a takeaway that I have lived with forever, which was he said he would wait until the art came in to design. And you know, that’s partly his confidence that he could come up with something. But I know he was super respectful and his main mission was just, “Don’t fuck up this art.”

But looking at both of your work—so intricate and so ornate—it’s hard to imagine that the process of assigning the art was independent of the design. Did you have layouts sketched out to work the illustration into? Or was it really just like, “I’ll get this back and then I’ll…”—what did Deb say—“Go make a masterpiece?”

Gail Anderson: We weren’t part of the photo assignments at all. So we received something to scan and then work with it. So it was a surprise.

Patrick Mitchell: So it was entirely a response to the photo.

Debra Bishop: Yes. I call that “reacting.” And I think we learned a lot about doing that. That was the game.

Gail Anderson: Even the illustration, right?

Debra Bishop: Yeah, I think it was a lot about reacting. And we had to do it fast.

Gail Anderson: When I got to Spot later on, it was assign multiple artists to do the same thing and give them lots of direction. And I was like, “Oh my goodness. This is so different. And difficult. And needs so much more, kind of, diplomacy.” That was a whole different beast.

But the Rolling Stone “moment” was opening the piece, and seeing something beautiful, and then responding. And always working with a headline, working with live copy as much as possible. You weren’t just sort of making it up and then putting something in place later.

And that came from all of us being unfamiliar with the technology and all coming from the old school way of doing it. And I’m sure now it’s quite different, but at the time, you waited until you had the elements and then you came up with an idea. You didn’t just, sort of, place things on a page.

Patrick Mitchell: But as an observing party, I would say that speaks a lot to your confidence, both in your own skills and your confidence in selling what you’re doing to your editors

Gail Anderson: There wasn’t really selling.

Debra Bishop: Yeah, we didn’t have to.

Gail Anderson: Right? We were so lucky.

Debra Bishop: Yeah. Fred did any selling, if there was any selling. But they trusted him. And that was his job. Visuals were his job. The one thing I will say about Rolling Stone design, which I think you would concur, Gail, was that we had a very strong format in the Oxford rule. So we could play. Almost anything would be fine within those parameters, within that Oxford rule. You still knew you were in Rolling Stone.

And it was such a strong brand framework that we could really play within. So oftentimes our type was separate—it was much harder to create a sort of seamless spread where you were reacting to the photograph. And we did that all the time, but oftentimes we could have a sort of a separate type piece opposite something else that was in that rule.

Gail Anderson: They became posters. You know?

Patrick Mitchell: In addition to the incredible photography and illustration—your typography! I mean, you guys had all of this custom type done. I know you worked with a lot of outside people, but you probably did a lot in house too. Unbelievable.

Gail Anderson: I know. Who’s got the energy now? What were we thinking?

Debra Bishop: I know. And a lot of times it was in person. And Gail dealt with them. Do you remember our visits from Jonathan Hoefler and Dennis Ortiz-Lopez? And illustrators! In those days there was no internet to send your artwork over.

Do you remember Philip Burke sending his piece—or walking it in? You know, he’s from Buffalo. And part of the joy that Gail was talking about was opening up the FedEx package. Right?

Gail Anderson: Yep. I remember meeting Marshall Arisman for the first time, and him telling stories about being a witch. And I’m like, “Who is this man, Fred? What?” And Paul Davis coming to the office. And these legends were coming in and Fred was always like, “Oh, you’ve got to meet, like … Oh! What?” That was so cool.

Patrick Mitchell: It was like a Renaissance, you know? Rolling Stone was ground zero for magazines. So great.

Gail Anderson: The one thing I remember though, that has nothing to any of this, was we were still in the old office. Deb, were you there then? Maybe not. David Cassidy came to the office. And all of us—of a certain age—we were kids, but we were all of a certain age, and he came in and people were like, “Who’s that?” And we’re like, “It’s David Cassidy!” And he was so tickled that we were just like, “Oh my God.”

Now of course people would’ve had their phones out.

Debra Bishop: I remember John F. Kennedy Jr. And we followed him around. He came in for a visit when George, his magazine, was just starting. And he came in and we followed him everywhere.

Gail Anderson: Oh yeah. Like you’d hold up some paper and go like, “Oh, good. Go down the hall.”

Debra Bishop: And one time, Madonna came in, but I, unfortunately, was on vacation or something. I missed it.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, this is before all of our time, but if you read either Jann Wenner’s book or Sticky Fingers, the non-Jann Wenner book, there’s a great story in there about Annie Leibovitz shooting David Cassidy nude for a cover. Very young David Cassidy.

Gail Anderson: Yes. I remember that cover. I remember that little bit of the cut there that you saw, and there’s a little hair [showing]. Like, “What? David Cassidy?” I remember.

Debra Bishop: Wait, one more story, Gail. Tell your favorite story about Rolling Stone. Do you have one?

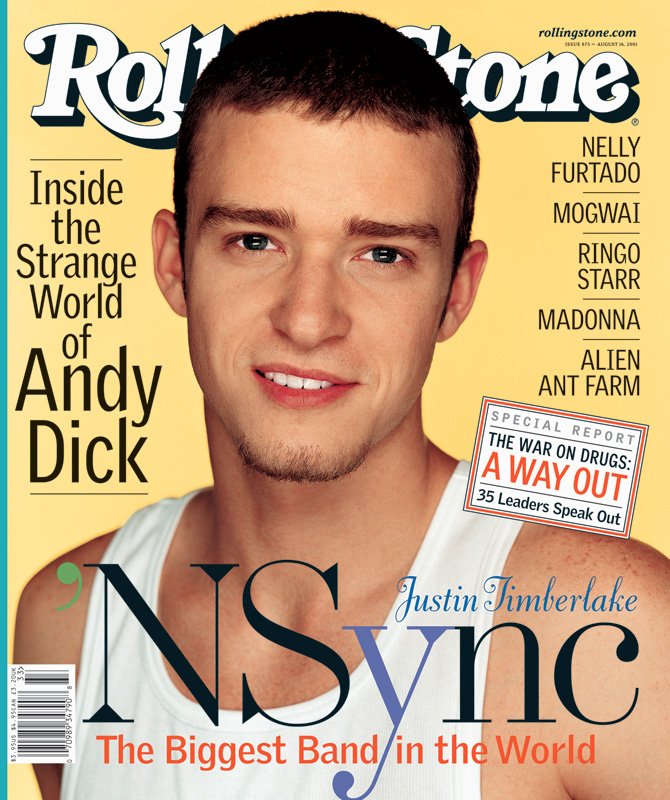

Gail Anderson: I remember NSYNC was there, and [Fred’s son] Hank came in. Fred brought him in hoping to meet them. And I sat out with Hank for the morning as they traipsed by and went in the conference room and did whatever they were doing. And Hank had a cover for them to sign. And he just sat there.

He was like three or four years old. And they came out to go to the bathroom, and they turned and everybody just kind of looked and Justin Timberlake said, “What’s up, chief? And Hank was just like, “What?” And then when he came back from the bathroom, he made the rest of them stop and sign autographs for Hank. And that was so sweet, “What’s up, chief?”

Patrick Mitchell: Gail, a lot of us, you know, again, watching on the outside, it seemed like if and when Fred ever left that you would be the obvious choice to step in there, but that didn’t happen.

Gail Anderson: He left. And I knew my days were numbered. It was going in a different direction. The real estate was getting smaller and smaller for what we did. And Jann wanted to, sort of, be more of a newspaper. And all the fancy stuff was, kind of, done. So I knew my days were numbered.

Patrick Mitchell: Yeah. I’ve heard rumors that Jann was maybe a little threatened by the massive success of the design of Rolling Stone.

Gail Anderson: I still worry sometimes when the design of anything is so successful, that whoever the boss is will start to believe that what the designers are doing, they’re just doing for the sake of awards and for the sake of design. And that they’re not on the same mission as everyone else.

So I don’t know if that’s sort of what was starting to happen a little bit then. But just the time was changing and there wasn’t the real estate to do the big openers. And Fred wasn’t really up for going in the direction that it was heading. And I only knew that direction, so I wouldn’t have been able to do anything else. And it needed a new voice. So it wasn’t a matter of promotion.

Patrick Mitchell: And you’d been there 14 years, right?

Gail Anderson: I’d been there 14 years and I was done. And I knew that I had to do something totally different. That I didn’t have another magazine in me at that moment because I felt like I had the best job ever. And how am I going to top this?

I need to just try something else because I have no obligations and let’s see what doing something else is like. And I put that out there into the world a bit and something wonderful and exciting happened that challenged me, and scared me. And I needed a good scare because I was starting to coast.

And going into a new job where you have no reputation to precede you, that it’s sort of starting over, was really hard. But it was what I needed. And working for a [former] classmate … at first I thought, “Well, this is going to be weird.” But it turned out to be okay.

Patrick Mitchell: Before we leave Rolling Stone, and maybe a bit inspired by Jann’s recent implosion, would you say women have been treated fairly or been given the same opportunities? It has come up often in our podcast and Deb has talked in the past about women being stereotyped in terms of what kinds of magazines they can design, which is incredibly unfair.

Gail Anderson: It felt like a man’s world. But I didn’t know or expect otherwise because, you know, it was a different era, and it was just the beginning of some women having a voice, some power, all of that. And so all of those people who were sometimes seen as difficult which is so wrong because they were working extra hard. That was really inspiring to see those women.

And looking back now, it’s like, wow. In my own little way, I hope I was, as the years progressed and I got older and older there, that I was one of those to an extent. People like Laurie Kratochvil, she was kicking ass there. And you thought, “Oh, like, she’s tough.” It’s like, really? Was she tough? Or was she just this woman doing this job and that’s what you needed to be to do that job.

Debra Bishop: … which you had to be.

Gail Anderson: Which you had to be. Exactly. And my fear now, even now in my old age is being seen as difficult or all those things that aren’t ascribed to a man when they kind of have to buckle down and mean business or do something difficult. All that. Sadly, it does still exist.

Patrick Mitchell: It’s unusual in creative work where you are in a real way in communication with the audience. You’re actually putting things out there to get a response. People are absorbing your work in their daily lives. Did that figure into your calculation for the next phase of your career in terms of doing work, maybe a little bit more in a vacuum? What part of the joy of your work was knowing that it was going into people’s mailboxes, real people around the world, directly to them?

Gail Anderson: I loved that the magazine was out there in the world. When I was at the Globe, Ronn would say, “It’s fish wrap.” And we’d sort of giggle. And then I was getting off the T and walking to, I was in Dorchester, and I saw the magazine on the ground. And then I was on the Green Line going home from Brookline. And I was like, “Wait, this is my Sunday magazine on the ground again!”

And I was like, “This really is fish wrap.” You look at it on Sunday and then you get rid of it. And that was like, “I can do whatever I want.” Because this is so ephemeral. And because Rolling Stone was every two weeks, it was sort of the same thing. We were just cranking and you didn’t really have time to, sort of, sit back and think about this. You did it for a few days, you put it out. Some of them are great, some of them aren’t. But they came in and they went.

Doing books and other things that sort of live forever, you’re like, “Oh God! I’m going to live with this mistake for a long time.” But the magazines just came and went and it was on this supercalendered paper. And I loved that I didn’t have to think about it too hard after the fact. And your mistakes went away and you tried something new. You just kept learning and learning.

“Who would say ‘no’ to making posters? It’s like, ‘I’m going to make Broadway posters? What?’ Of course I’m going to do that. Of course I’m going to say ‘yes’ to that.”

Patrick Mitchell: So you left Rolling Stone and you went to Spotco, which was a really amazing agency that focused on design for the entertainment business, especially Broadway. I saw a video of you talking about Spotco and in the video they taped you walking through Times Square.

Gail Anderson: Oh, yeah. I did that!

Patrick Mitchell: And it showed all of your posters and, you know, I’m killing the question I just asked because that exemplified how you can be in the middle of your own work out in the real world. Although those of us who aren’t on Broadway don’t see it. But what was it about Spotco that felt right after leaving Rolling Stone for you in your next phase?

Gail Anderson: It seemed like, “Who would say no to making posters?” And that’s what I saw that job as, initially. It’s like, “I’m going to make Broadway posters. What? Like, of course I’m going to do that. Of course I’m going to say yes to that.” And it turned into so much more and was so much more complicated than posters. Posters were the least of it at a certain point. I thought, “This is something I love. I know theater. I want to stay in entertainment.” And the company was growing.

Drew Hodges, my classmate from SVA, wasn’t really able to manage the design part of it anymore because it was leaps and bounds there. And he had to sort of be the “showman” to talk about the work and to work with the clients. And had gone from Spot Design, which was a design studio to Spotco, which was an advertising agency.

And so I was sort of charged with the design folks. And there was another creative director, Vinny Sainato, who actually just passed away, who was the advertising art director. And the two of us worked together-but-separately, and he and his folks took what the designers made and then did the advertising. But Drew learned that the money was in the advertising and not in the design.

And it was brilliant, and I saw so many shows, I visited so many interesting places, I learned so much. I had my work ripped to shreds by so many producers and had the designers work ripped to shreds and had to learn how to defend the work and how to be polite to those I wasn’t that fond of.

And I saw Drew present work to clients and I was like, “Where’d you learn to do that? It was brilliant.” And he was so gifted at that. And I thought, “I can’t do that.” Like this is going to take years. And he invested in me and eased me into that part of the job. And I was never great at it in the end, but I could get by and the clients liked me and trusted me.

And so that was good. And there were some really wonderful people, but also some very difficult people. And after years of the Globe and all my wonderful friends, and then Rolling Stone, where everybody was like, “We’re all doing great stuff together.” And then this was like, “Wait! Like I have to defend this? I have to show eight, nine versions of something? Are you kidding?” And have it up pinned to the wall. And we take three of them down and we take three more down. And then that was so anathema to the Rolling Stone days.

Debra Bishop: So, it was much more iterative. It was much more repetitive. Drew says, “Gail is a true Broadway baby. She brought her brilliant sense of style and typography to the theater and moved forward how sophisticated those visuals can be.”

Gail Anderson: Aww.

Debra Bishop: So, what was the process of a theater poster, just, kind of quickly?

Gail Anderson: Reading the script, and actually learning for me, learning to read a script and let it stick in my head. That was the hardest part because it was so different from reading a story. And I’m, like, reading in two voices and three voices and I’m like, “Who’s saying what?” And sometimes I’d read out loud to myself at home because I was like, “I don’t even know what’s going on anymore.” So there was that.

And then working with the designers—I tried to pair people because sometimes some of these were like, “I’m smart, but I’m not that smart.” And some of the stuff was … it was pretty heady. Like, “Give me a musical!” But when we got into the plays, we worked together so that nobody ever felt like, “I alone must fix this.” You know, people work together to solve a problem because we were showing so many versions.

You couldn’t expect anybody to come up with 10 great versions, nine of them which will be ripped to shreds and one that’s going to be pieced together with a piece from the one at the other end of the hall. It was tough. And there were so many comps and so many good comps. And we would keep the comps like, “Let me save this idea because I can try it again at some point.”

Debra Bishop: It was a library of comps.

Gail Anderson: Library of comps. Yeah. That was a hard job, but I learned so much. But I also learned why people stay in their lane and go from magazine to magazine or whatever, because making the shift is really hard.

When I was at that farewell for Fred at SPD, people were like, “You’re so smart! You got out of this. How did you know? You tried something else.”

Patrick Mitchell: It feels like you and Paula maybe started this theater poster situation at a similar time. Is that true?

Gail Anderson: Well, no. She started it, started the groovy stuff with The Public. And she’d even done something that transferred from The Public to Broadway. But I had to redo something that she’d done, that they didn’t want to use for Broadway. And I was like, “Oh, no thanks!” And I’d think, “Do I have to, like, write her a letter and tell her?” That was a little scary.

Patrick Mitchell: I’m not a historian of Broadway theater design, but it seems like that was the beginning of a new way of creating, designing...

Gail Anderson: Oh yeah, definitely. Yes. Oh yes, yes, yes. And there were just a few people who did the posters. A guy, “Fraver” [Frank Verlizzo] was a name that always popped up. And things were very glossy. And the stuff that Spot was doing was not as shiny, and that was very appealing to me.

Patrick Mitchell: And one could draw the conclusion that you sort of brought editorial thinking to that kind of work.

Gail Anderson: Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: Storytelling.

Gail Anderson: Storytelling. Yeah. But, all of a sudden, I had these bigger budgets to work with. And so many people to please. And that was very different. And time, all of a sudden. With the magazine there wasn’t time to do it over and over again. And with this, it was like, “Well, let’s go back and spend a week.”

“Oh my God, really?” And just get somebody else on board to crank out the 15th version of something. And, you know, these were new ideas, not just a little tweak to something. And it was a great lesson and something that I do in school now. It’s like, “We’re going to do lots of these.”

Debra Bishop: Let’s talk about your decision to leave Spotco. Did you know what was coming next?

Gail Anderson: It was, like, that was kind of ending. In the same way that’s it’s like, “Ah, it’s time for something new.” But really it was that I had elderly parents who required care, and my siblings and I were going in circles, and I realized I just couldn’t work full time anymore.

I had to be down there and do something that allowed me to put in my time, since I was the farthest away of the siblings from their retirement community in Jersey. It was hard, you know? I had had those in-between years of, “What do I do?” And the consistent thread was teaching.

Debra Bishop: So you chose to go to the School of Visual Arts, obviously, when you were young. Did you ever think, that you would end up being the head of design in the very program that you went into?

Gail Anderson: No. But when I came on, Tony Rhodes called—this was after, again, a random call—Tony Rhodes, the executive vice president, called after my father died. And I’d done some posters for the school and he called on a Friday and said, “What would you think about working here?” And he told me the salary to run the design studio for the school. And he said, “Just give me an answer on Monday.”

I was like, “Wait! What?”

And the next week I went to talk to him and I thought, “You know what? Like, why not?” Again, like, let’s just try something totally different. And, once again, I was lucky that it turned into something.

But I never thought about Richard Wilde’s job. I was running the studio and enjoying that and teaching, and again, you have that moment like, “I’m going to join a gym, and I’m going to ….” And then life changes again. The gym goes out the window. The first thing to go, of course, is the thing that’s good for you.

And people thought, “Oh, well, Richard’s going to retire. Gail’s the successor.”

I was like, “No.”

And then Richard came in one day and said, “I’m going to retire, and I think you should have this job.”

I was like, “Yeah.” So, out the door went the gym, and I moved across the street

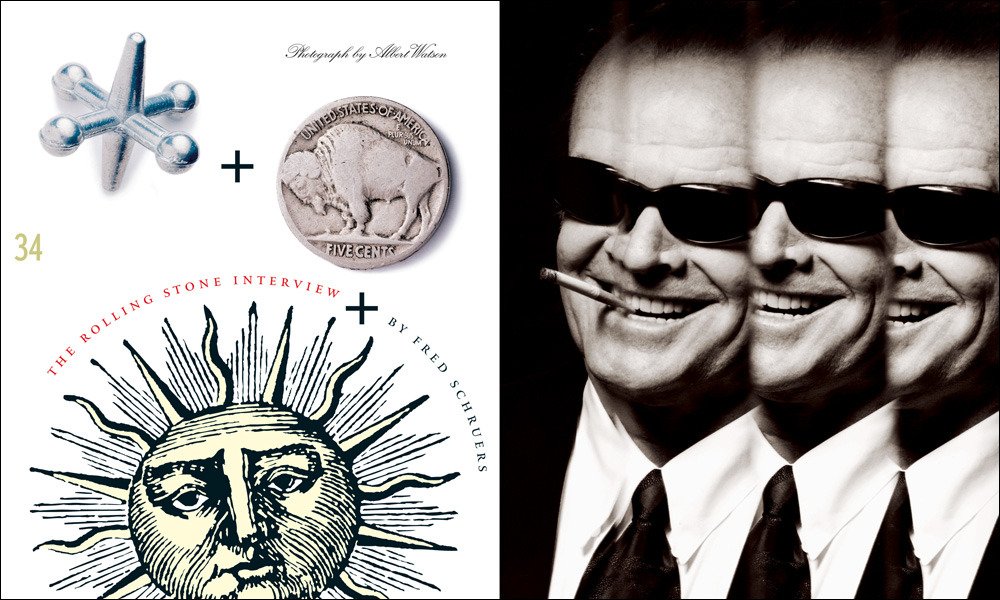

A sampling of Anderson’s work at Spotco

Debra Bishop: So sometimes on this podcast we talk about magazines as if everything’s, you know, the way it used to be. But we’re curious, as a teacher at a school that has turned out its fair share of magazine makers over the decades, does anyone still talk about magazines there? I mean, are magazines part of the curriculum?

Gail Anderson: We added an extra class because there’s been a renewed interest. Bob Best was teaching editorial, and still is. And Matt Lenning started teaching a couple of years ago because they were like, “We want more magazine stuff.”

I’m like, “Really? Yes, please.”

And so now Matt’s done and I’ve got to find someone. Anybody out there who wants to teach an editorial design class?

Patrick Mitchell: What does this new thing look like? What are their interests?

Gail Anderson: They sometimes see it as these sort of “sullen” journals. You know, of the sort of sad-looking, thin people standing there looking in their clothes. So it’s like, let’s try something else. And not just the...

Patrick Mitchell: Like Unhappy Hipsters? Do you remember that?

Gail Anderson: Yes! Unhappy Hipsters! Yeah! But they’re into the architecture of the page. They’re curious about that. And some of them are actually into the storytelling, which has been wonderful.

Debra Bishop: Storytelling and editorial systems, because that’s very helpful when you’re designing things like websites, etc.

Patrick Mitchell: Well, also throw in the fact that, unlike when we were in school, they can actually produce a fully-printed, full-color, stitched magazine … for nothing.

Gail Anderson: Nothing. Yep. And you can do it from the printer at school, from the copier. And it binds it and staples it and just like, there’s your magazine right there. And then there’s a zines class because they love that too. And it just started to happen a couple of years ago, so that’s been wonderful.

Debra Bishop: Well, there’s a lot of indie magazines out there. So Steve Heller, the wonderful Steve Heller, who you have done at least 14 books with, authored with Steve Heller. How did you ever fit that into your busy career?

Gail Anderson: The first one, because I’d gotten to know Louise and met Steve when they were dating, so that’s how long ago this is. He would come to the office at Random House and scoot by. And I was like, “Who’s that man?”

And she’s like, “That’s my boyfriend.”

I was like, “What?”

And he just loved her so much. And I said, “If he ever needs help with a book, I would love to help him.”

And she was like, “I’ll tell him.”

And then he got in touch and was like, “I could use some help with the book.”

Debra Bishop: So where were you working when you started the first one?

Gail Anderson: I was at Rolling Stone.

Debra Bishop: Oh my goodness! Okay.

Gail Anderson: And I was living with my parents. It was very early on, so I was in the Bronx again. And he’d say, “Okay, meet me at 6:30 [am]. So I’d go down at 6:30 or 7, because he would meet illustrators then, and go through their portfolios, like rapid fire. And then say, “No, I can’t use you.” And then look at the next person. It was so ballsy and they were just, like, lined up.

And then he would talk to me and we would talk about, we were working on a book called Graphic Wit. And this is, again, pre-internet, so it was like faxing people and sending mail and getting packages. And I really enjoyed him. And he was smart and funny, and I didn’t know what he was talking about most of the time, so I was always taking notes.

And you make no money with books, but working with him I learned so much. And I learned about design outside of New York City, and then outside of the state and outside of the country, and then around the world, and...

Debra Bishop: You must have been working 24/7! Steve says, “She is a perfect fit for BFA”—meaning Bachelor of Fine Arts at SVA—“as she was a perfect fit for the Visual Arts Press. Her typographic playfulness is without equal. It’s what she lives for.”

Gail Anderson: Yeah. Aww.

Debra Bishop: Yeah. I remember you being very shy and soft spoken.

Gail Anderson: Still am.

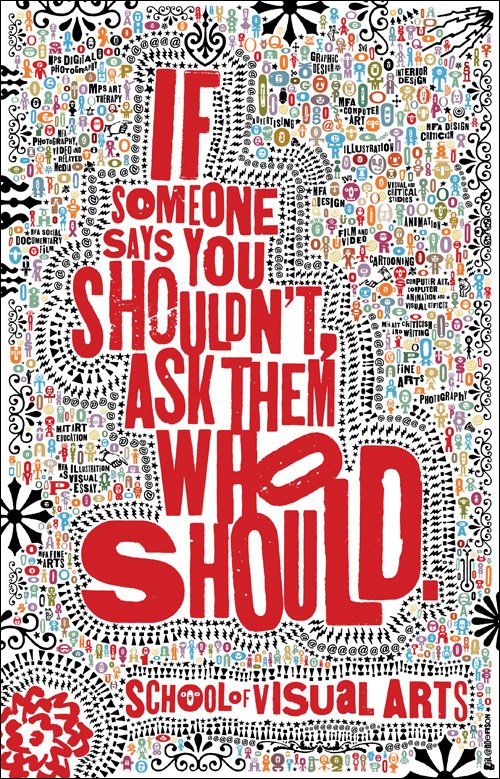

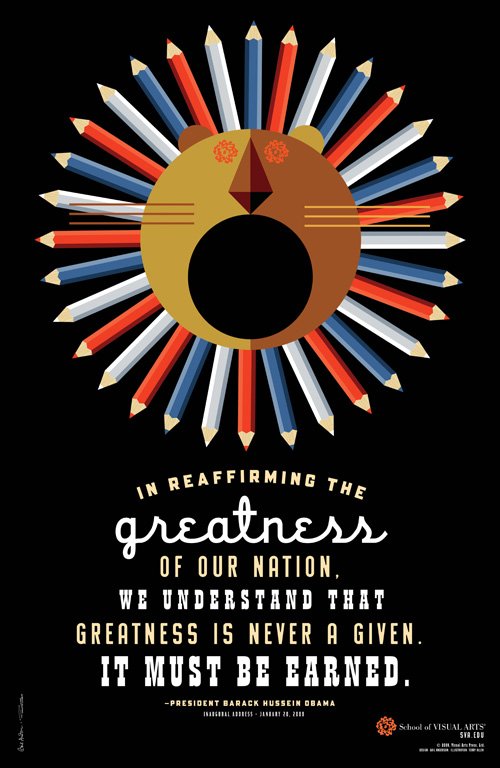

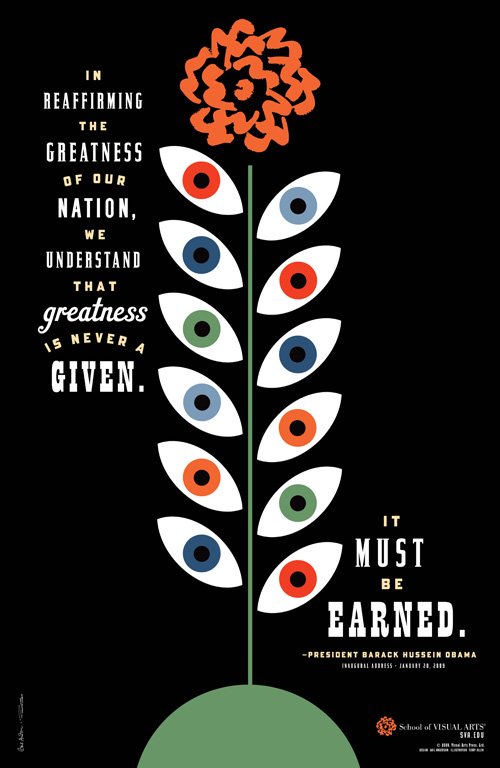

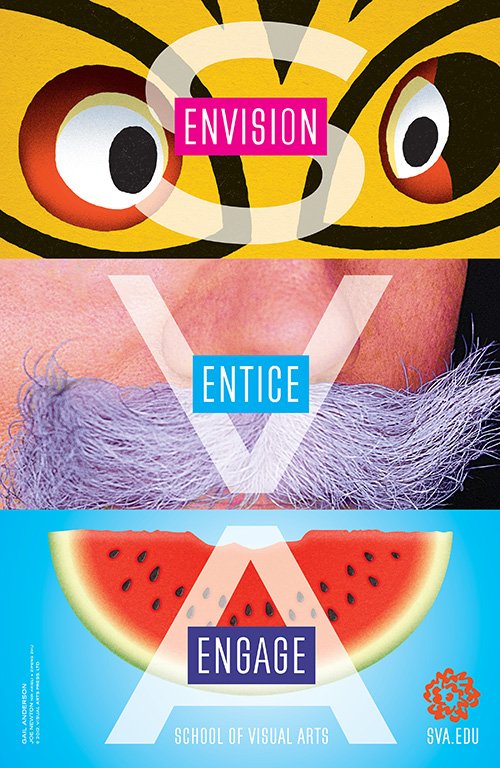

Anderson’s poster work for SVA

Debra Bishop: And so how did you overcome it and end up traveling all over the world speaking and lecturing about graphic design? I need to know this.

Gail Anderson: Because it’s easier to talk to a bunch of strangers than it is to a few people. I learned that instantly. I can talk to a sea of people I don’t know, but if I’m in a room with a few people I do know, I’m like, “Oh, I’m going to say something stupid. Ugh.” And it’s one of those things that you just keep doing it and you know, you get better at it. And then you get old and you don’t give a shit anymore and you’re like, “Well, this is what I think.”

Debra Bishop: Where have you been? You’ve been all over the place. What’s your favorite place?

Gail Anderson: I was in Ireland this summer in Connemara, on the West Coast with the sheep. It’s so much fun and you’re just making stuff by hand. And I was just there sort of visiting and I did some talks, I spoke in Galway and in Dublin, and there was a radio show, and then I was at the program [Design West Summer School], and I’m going to go back this summer and teach and it was life changing. And I’m like, “Those are sheep!”

First of all, I’m driving on the wrong side of the road. You know, so stuff like that, it’s to visit someplace you wouldn’t otherwise. I spent time with Carin and Jim, with Carin Goldberg and her husband, Jim Biber, in Slovenia, years ago. We were in Ljubljana speaking at a conference together. And so you end up making these little connections to people in a different way and getting to know them.

And it’s been really nice to meet folks and to visit places that I may not get to otherwise. Yeah. I’ve been really lucky. And because I still am ‘Jamaican with three jobs,’ I’m like, “Okay, I’ll do it. Yeah. Okay.” So if I don’t say yes, they’re never going to ask me again.

Debra Bishop: I hope you have time to relax once in a while, Gail.

Patrick Mitchell: Gail, you’ve talked about therapy a lot and I don’t want to pry into your personal business …

Gail Anderson: … I could have gotten her on the call, too …

Patrick Mitchell: Can you share what, you know, maybe the most valuable lesson you’ve learned or what’s maybe changed your thinking after doing all this work?

Gail Anderson: Oh, yes. A little less putting myself down, you know? A little more confidence. A little less ruminating, and blaming myself, and taking everything personally, and all that.

Having somebody who isn’t in the thick of it, who will listen to it, but who doesn’t have to be like, “Okay, I gotta go now,” until she literally has to go now, so I’m not burdening a friend with my whining. I was like, “Oh, that’s what this is for.”

And that’s been great, to work with someone through all these different transitions who’s been really supportive and who knows the whole story at this point, because it’s been so many years!

Patrick Mitchell: Same person?

Gail Anderson: Yeah.

Patrick Mitchell: That’s great.

Gail Anderson: Yeah, it’s really funny. And in person, Zoom, whatever.

Debra Bishop: Has she helped you with a habit that we both have, which is collecting, hoarding?

Gail Anderson: We’ve spent some time discussing that, yes. At one point she’s like, “You want me to just come over and help you?” She just threw back the curtain. It’s like, “Oh, for God’s sake!”

Debra Bishop: I need to do some Marie Kondo-ing myself.

Patrick Mitchell: What was in your hoarding/collecting wheelhouse? What was “the thing”?

Gail Anderson: It was salt and pepper shakers. Hundreds. And they’re really fun and silly. All that stuff that we all collected that I just kept going with. And now I’m just like, “Nope, I don’t want anything.” I still have all this stuff that I still love, but I kind of don’t really want at this point. But nobody else wants it.

Debra Bishop: Brimfield is up and going again. We can each do a booth. I have many tins—you remember I used to collect type tins?

Gail Anderson: Yes, I remember.

Patrick Mitchell: Are you at least able to navigate to your bedroom, through your apartment?

Gail Anderson: Okay. Where I am now—I’m up in Woodstock—and there’s a lot of stuff here. In my apartment [in the city], there is a couch that I sleep on, and some boxes, and that’s it.

Before the pandemic, they were doing electrical work, and everybody had to move all their stuff to the middle of the rooms to do the electrical work. And then the pandemic, so all the stuff stayed for a year in the middle of the room, but I’d gotten rid of a lot of things because I was in my like, “Okay I’m done.”

So I had almost no furniture left. And I thought, “Well, I’m going to live simply there.” And I don’t even unfold the couch. I’ve just been sleeping on the couch for the last year. So I’ve also gotten lazier. But just to have these bare walls, and no stuff …

Debra Bishop: Yeah, it’s kind of what happens naturally as you get older. You just don’t need it.

Patrick Mitchell: We wanted to hear about your house in Woodstock, though.

Gail Anderson: Oh, that’s been my sanctuary these years.

Patrick Mitchell: Milton [Glaser] played a role in this, didn’t he?

Gail Anderson: Milton. Milton! Yes. Milton connected me with the architect, chose the colors, looked at the plans, looked at photos. He was, “Here’s what you’re going to do.”

And I was like, “Okay.”

Debra Bishop: Wow, Gail. Little known fact!

Gail Anderson: Yep. And I remember sending him pictures because I was mocking up colors in Photoshop and he’s just like, “Nope. No.”

“Okay!” And he never came over.

Patrick Mitchell: Was Milton in Woodstock too?

Gail Anderson: Yes, Milton was at the other end of the road on, like, 50 acres or something with this Italian sign. And I would go there. And he sold that house to downsize and bought a smaller house, of course, a beautiful house and had that renovated.

But we would have lunch sometimes and he said, “Well, I’ll be dead soon. So I’m going to give away all this.”

I was like, “Oh my God!” Not, “I’m dying. I’ll be dead soon.”

And so he was giving away all the stuff, and right before he died, gave me a couple hundred posters to give out at school. And these were on foam core, some of them signed, some prints. And he’s just like, “Yes, give them to faculty”

So I’ve been giving away Milton posters for the last couple of years. But I have to like, “Do you know who this is? Do you know?” Like, “I’m not giving it to you unless you take care of it.”

Debra Bishop: I hope the kids appreciate that.

Gail Anderson: No, not the kids. Faculty. Faculty. Not the kids. And I’ve been framing some of the really rare ones and hanging them at school. But, yeah. He made all the choices and I just went along.

Patrick Mitchell: What a neighbor to have. We’re going to get to the big question in a minute, but I sort of want to wrap it up here by saying, you know, you have really lived a design life. It’s so awesome to hear about and to learn about. What is the one thing that you’ve made that you’re the most proud of?

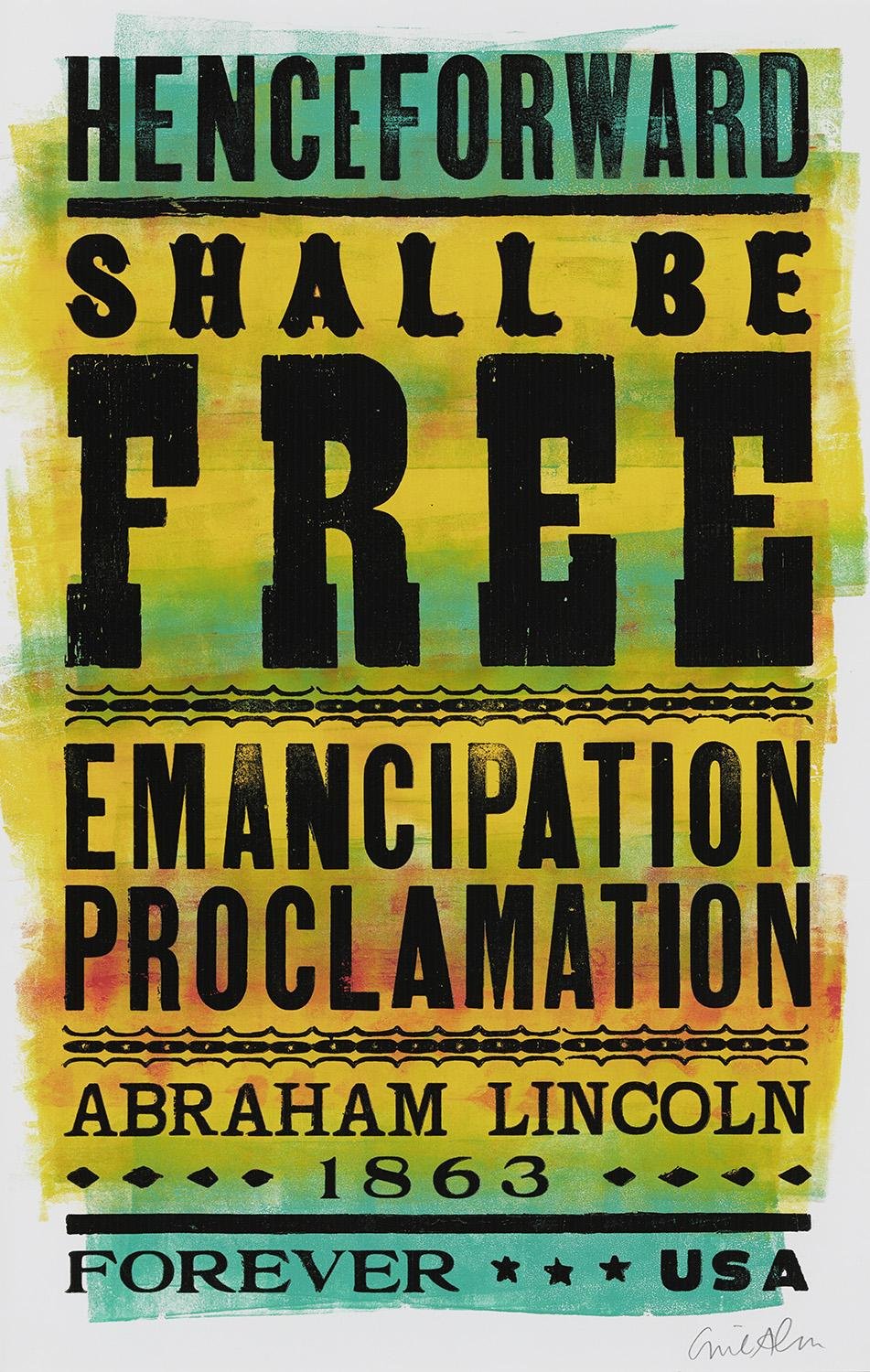

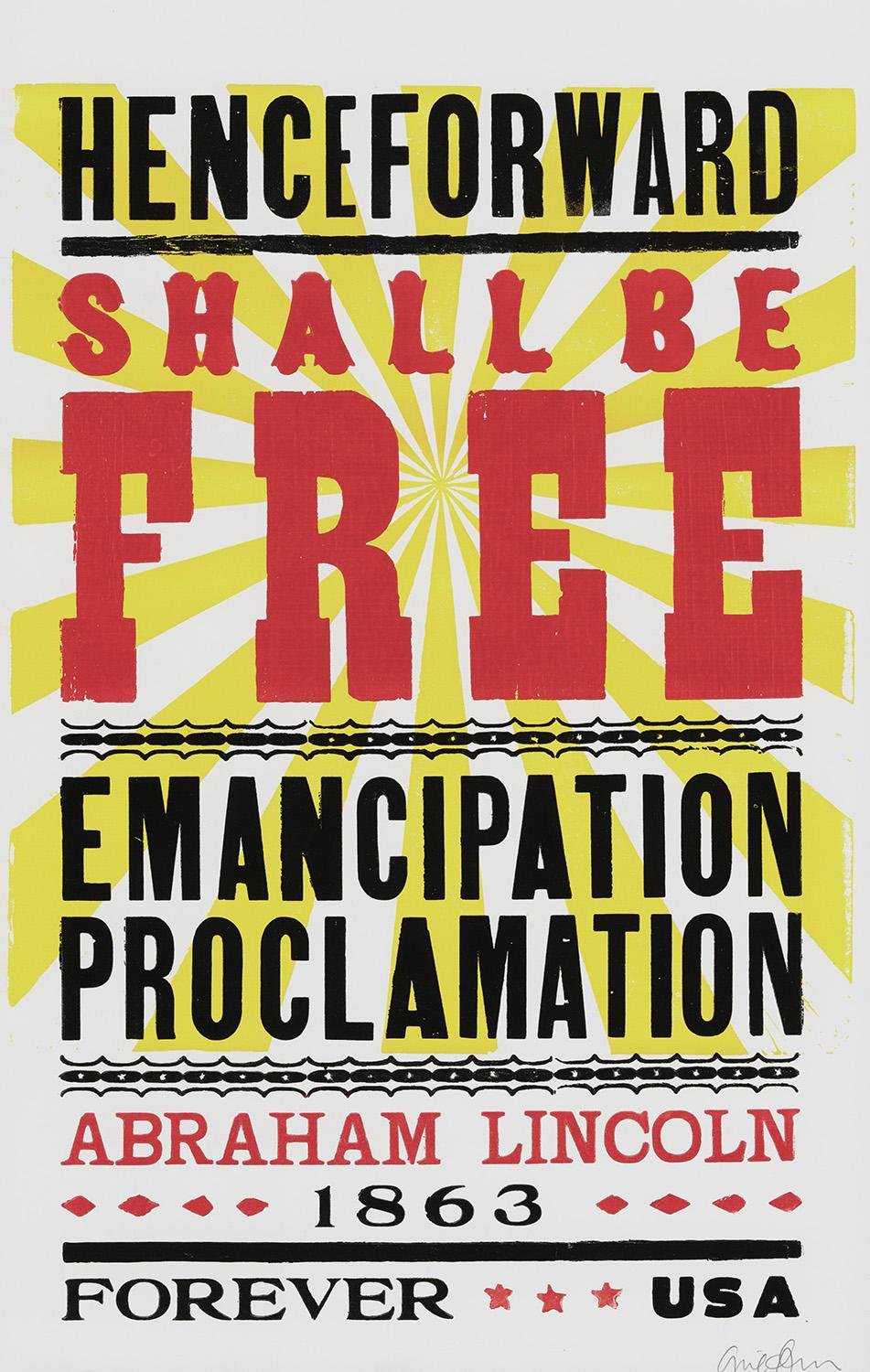

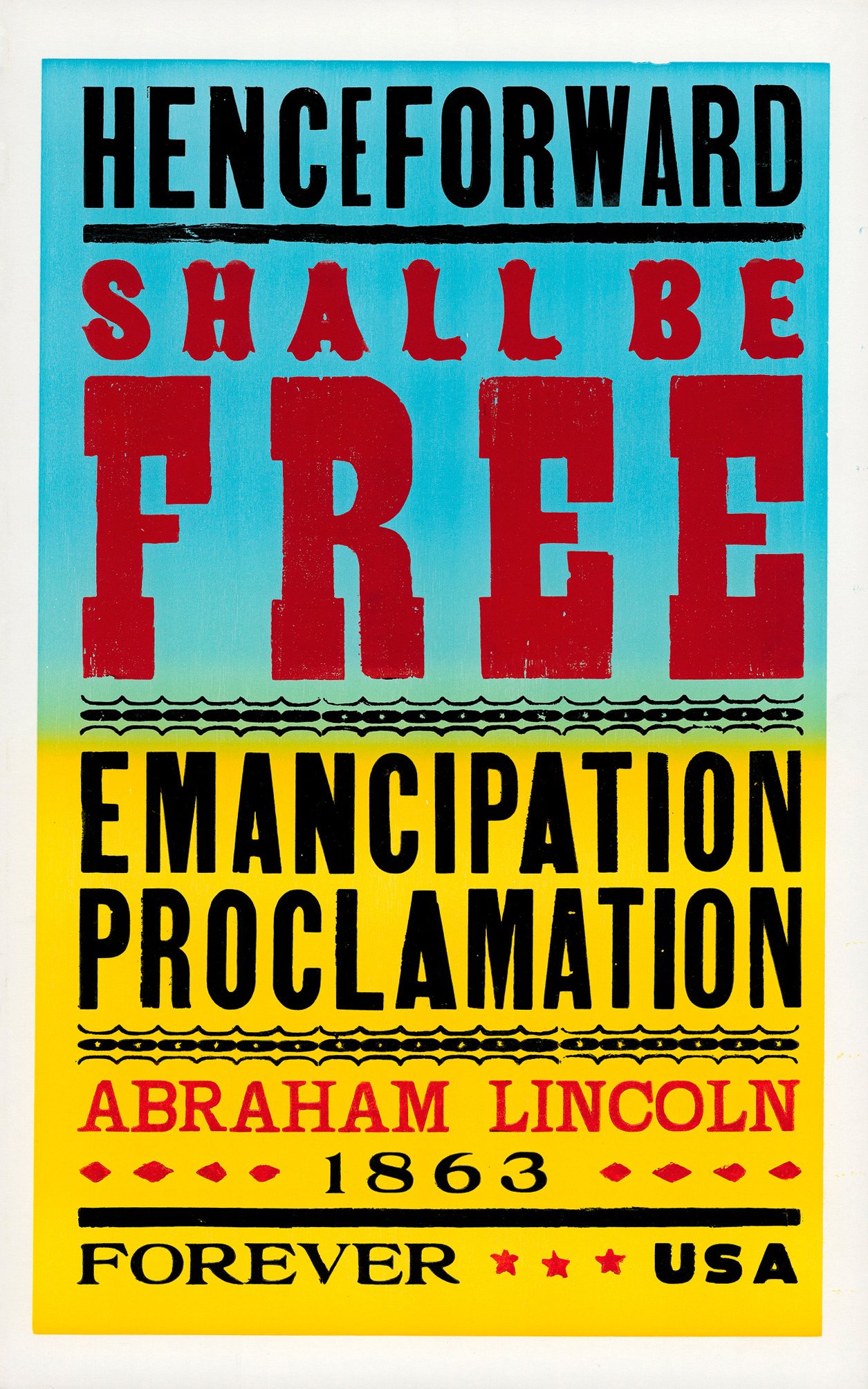

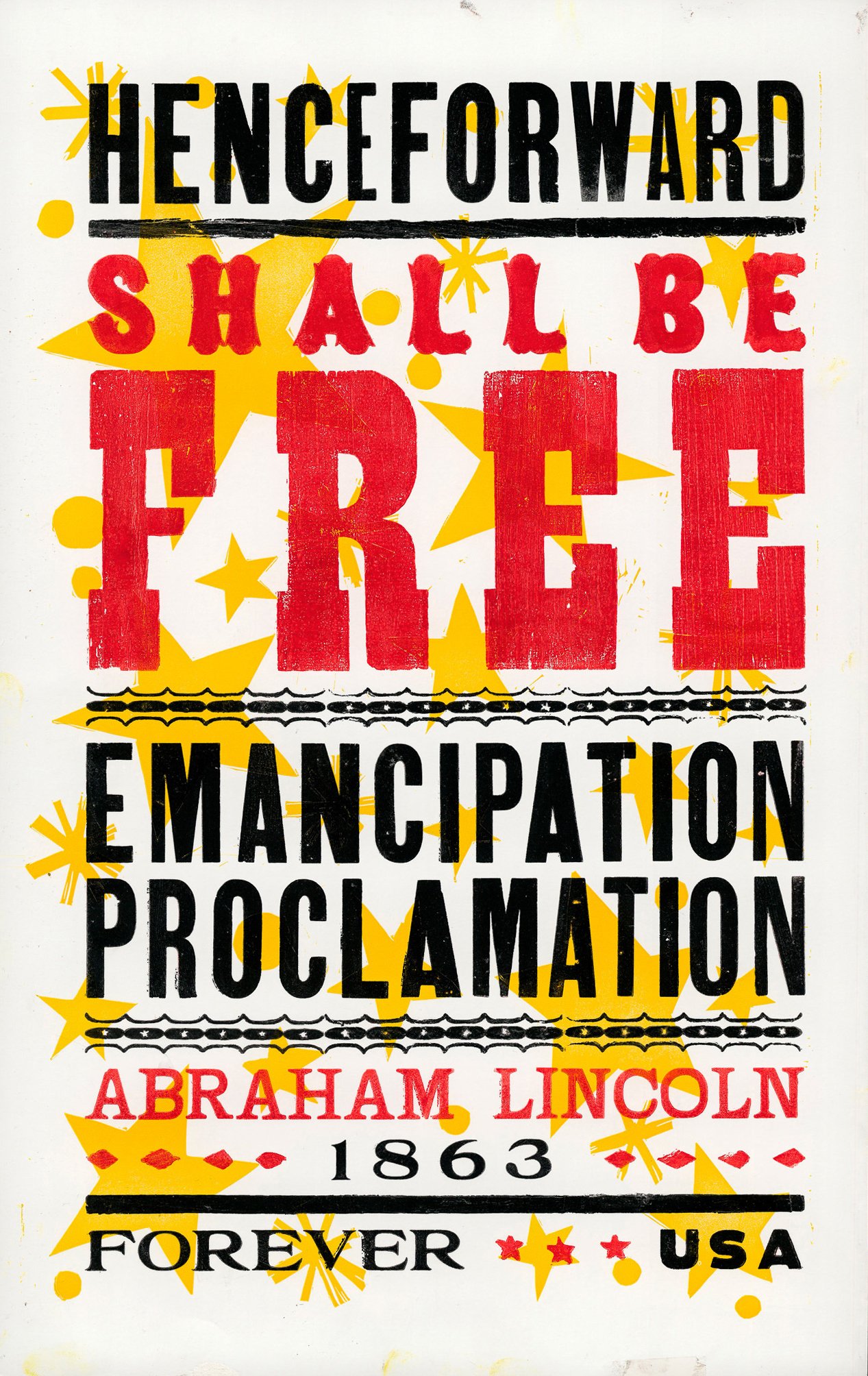

Gail Anderson: Both the biggest and smallest thing was the postage stamp in 2012. It was released in 2013 for the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. That was so cool. To, again, do something that so many people saw, you know, because my world had gotten a little smaller and then it got bigger again by having a stamp out there.

And since then I started serving on the Citizen Stamp Advisory Committee for the Postal Service and I just came back from Des Moines, where I was judging the federal duck stamp competition. And so I have turned into this philatelist late in life. I have a new vocabulary word.

Debra Bishop: Yeah, can you translate that?

Gail Anderson: I’m a stamp person!

Patrick Mitchell: But that particular stamp that just had so much extra meaning.

Gail Anderson: Yeah when I got the call to do that, I was just like, “Do you want me to come down to Washington tomorrow?” It was just like … it was the thick of the worst of dealing with my parents, and I left them in LeisureTowne and got on Amtrak and went down to DC.

And the one thing that Antonio Alcala, the art director, said was, “Don’t do type.”

I was like, “Wait. What? I can’t really do anything else.” And then I did type.

Patrick Mitchell: All right. Our tradition, at the end of our Print Is Dead episodes, is to ask the Print Is Dead Billion-Dollar Question. And that is that a very rich person, take your pick—Warren Buffett—has an offer that you can’t refuse. He wants to give you a blank check, but with one caveat: you have to use it to create and launch a print magazine.

Gail Anderson: I have to take my money to launch a print magazine? What?

Patrick Mitchell: Well, it depends. When does it become your money? That’s a good question.

Gail Anderson: Well, it just did.

Patrick Mitchell: What would you make?

Gail Anderson: What would I make? Well, I kind of want to bring back Spec or 16. Can I bring back MAD magazine in all its glory? Can I use my money for that? MAD magazine affected everything. You know, just, “Yes, please!” A combination of SPY and MAD. That would work for me.

“I’m a stamp person!” Anderson was selected in 2013 to design a stamp for the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Below, her collaboration with Hatch Show Print to make commemorative posters of the stamps.

MORE LIKE THIS…